Bones Howe, Crystal Gayle and Tom Waits during the recording of 1982's One From The Heart soundtrack.

Bones Howe, Crystal Gayle and Tom Waits during the recording of 1982's One From The Heart soundtrack.

When label boss David Geffen teamed respected engineer 'Bones' Howe with an unknown and very strange songwriter called Tom Waits, he set in motion one of the great artist-producer partnerships.

There might not have been an odder long-term pairing in the music business than 'Bones' Howe and Tom Waits. The engineer and producer was responsible for a string of the artist's classic albums from the 1970s and early '80s; yet, on the face of it, the two could not have been more different.

Howe was born in 1933, in Dayton, Ohio, the son of a stockbroker. Growing up in Florida, Howe had the seemingly classic experience common to those who would become audio engineers later in life, taking apart radios and putting them back together, which put him on a course for engineering studies at that most slide-rulish of institutions, Georgia Tech, where he also played drums in a jazz band.

Tom Waits, on the other hand, was the paradigmatic lounge lizard, barely coherent before the break of noon and apt to prowl the seedier boulevards of Southern California till the wee hours, his pungent character observations of hookers, voyeurs, junkies, small-time crooks, pimps and other social debris later set to music on the guitar and the piano. It took an eye and ear particularly sensitive to the unusual to see the gems in Waits' scraggly goatee. But sighted they were, by Herb Cohen, who managed the equally idiosyncratic Frank Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention. Cohen signed Waits in the early 1970s and brought him to another maverick, David Geffen, who had recently started Asylum Records, home to the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt. Geffen clearly had a sense of what would work for pop music, and his judgment was borne out by the Eagles' cover of Waits' 'Ol' 55', which transformed the slit-eyed nocturnal visions of the raspy-voiced composer into soaring harmonies that glistened on FM radio.

Tom Waits, on the other hand, was the paradigmatic lounge lizard, barely coherent before the break of noon and apt to prowl the seedier boulevards of Southern California till the wee hours, his pungent character observations of hookers, voyeurs, junkies, small-time crooks, pimps and other social debris later set to music on the guitar and the piano. It took an eye and ear particularly sensitive to the unusual to see the gems in Waits' scraggly goatee. But sighted they were, by Herb Cohen, who managed the equally idiosyncratic Frank Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention. Cohen signed Waits in the early 1970s and brought him to another maverick, David Geffen, who had recently started Asylum Records, home to the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt. Geffen clearly had a sense of what would work for pop music, and his judgment was borne out by the Eagles' cover of Waits' 'Ol' 55', which transformed the slit-eyed nocturnal visions of the raspy-voiced composer into soaring harmonies that glistened on FM radio.

Bones Howe, by this time, was already a respected engineer and producer. He became one of the staff engineers at Radio Recorders in May, 1956, where he turned his jazz sensibilities on artists like Mel Torme, Ella Fitzgerald and Ornette Coleman (see box opposite), as well as doing scores of pop sessions with crooners like Frank Sinatra. In 1961 he took up an offer from Bill Putnam, who had founded Universal Audio, to take a staff position at his new studio in Los Angeles, United Recording (Putnam later bought Western and joined the two facilities) cutting tracks and sometimes playing drums on records for artists like the Grass Roots, Jan & Dean and the Beach Boys.

Howe was one of the first of his cohort to make the move to freelancing, and engineered for the legendary producers Lou Adler (the Mamas & The Papas' 'California Dreamin') and Snuff Garrett (Gary Lewis & the Playboys' 'This Diamond Ring'), before he moved into production himself. His first pass at that resulted in the number one hit for the Turtles, a cover of Bob Dylan's 'It Ain't Me, Babe' in the summer of 1965. Howe followed that up with hits for the Association, the 5th Dimension ('Up Up And Away' and 'Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In' were both top 10 singles) and others, and by the end of the decade had made a move into film and television, becoming the chief engineer for the 1967 Monterey Pop concert movie and Elvis Presley's critically acclaimed 1969 Christmas special broadcast.

Tom Waits, meanwhile, was blossoming into a serious composer, albeit a strange one, more attuned to the beat poetry of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg than the surf and pop hits that were Howe's meat and potatoes. David Geffen put them together, and their shared affinity for jazz kept them that way for a decade.

Tom Waits, meanwhile, was blossoming into a serious composer, albeit a strange one, more attuned to the beat poetry of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg than the surf and pop hits that were Howe's meat and potatoes. David Geffen put them together, and their shared affinity for jazz kept them that way for a decade.

From Singles Acts To Singer-Songwriters

"It was 1970 and Carole King had made this record [the best-selling Tapestry, featuring the number one single 'Jazzman'] with Lou Adler with her just sitting at a piano," Howe recalls. "Then there was James Taylor and he had hits and then there were all these singer-songwriters, as well as the country-rock groups, like Poco and the Eagles. At the same time, FM radio was breaking in a big way and you could get five-minute cuts played on the radio. This was pretty different stuff. Now there were artists getting signed based on their ability to create a message that listeners could relate to.

"David Geffen called me — I had known him since the Association days — and he told me he had an artist who had made this one record for him [1973's Closing Time] and he thought because of my background in jazz and pop that we'd make a good pair. David was telling me that the business was changing and that it would be good for me to work with a singer-songwriter. Al Schmitt, who I helped train at Universal, was already working with Jackson Browne. I was a fully fledged producer by then, but it was time to follow where the business was going.

"David Geffen called me — I had known him since the Association days — and he told me he had an artist who had made this one record for him [1973's Closing Time] and he thought because of my background in jazz and pop that we'd make a good pair. David was telling me that the business was changing and that it would be good for me to work with a singer-songwriter. Al Schmitt, who I helped train at Universal, was already working with Jackson Browne. I was a fully fledged producer by then, but it was time to follow where the business was going.

"I sat in David's office and he played me Closing Time and a few demos that Tom had cut. He was playing guitar on them, and it sounded to me like he was trying to be Bob Dylan. But you listen to a song like 'Grapefruit Moon' and you can hear the jazz tinge to it. There was a quality to him that I could relate to in that. His chord changes and song structures were like jazz. He was singing raps before there was rap, so it was really more like beat poetry. His first producer was Jerry Yester [producer for the Lovin' Spoonful] who had done the Association records after I had finished with the group. They were trying to do this San Francisco psychedelic thing and it was a total failure, and David felt that Jerry couldn't take Waits in the direction he needed to go. But David knew the opportunity went both ways, and he said to me, 'This is your chance to get into album artists, not just pop singles.'"

The first meeting between Howe and Waits set the tone for their relationship. "I told him I thought his music and lyrics had a Kerouac quality to them, and he was blown away that I knew who Jack Kerouac was," says Howe. "I told him I also played jazz drums and he went wild. Then I told him that when I was working for Norman Granz [founder of Verve Records, manager and producer for Ella Fitzgerald and one of the jazz idiom's most talented entrepreneurs] Norman had found these tapes of Kerouac reading his poetry from The Beat Generation in a hotel room. I told Waits I'd make him a copy. That sealed it."

The Past Prefigures The Future

Recording jazz records was Bones Howe's earliest passion, and he recalls three nights, five months apart, in 1959 when he engineered alto sax legend Ornette Coleman's first two albums for Atlantic Records, which many would come to regard as cornerstones of jazz's avant-garde. The Shape Of Jazz To Come, recorded on May 22, 1959, and Change Of The Century, recorded on October 8-9, 1959, were the first to use this monumental quartet, with Charlie Haden on bass, Don Cherry on trumpet and Billy Higgins on drums. The records were recorded at Radio Recorders, Studio B, with Neshui Ertegun, brother of Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun, producing.

"The thing about doing these records was that the musicians set up the same way they rehearsed in Ornette's apartment in the Crenshaw section of Los Angeles," Howe remembers. "If you can make the musicians comfortable, make them feel like they're in a familiar place, then you can get some amazing things out of them.

"I set them up in a square, one in each corner of an imaginary room in the studio, close together, all facing the centre of the square. I had set up the microphones before they got there: I had an RCA 77 on Ornette's alto sax — the white plastic one he was notorious for playing — and a 77 on Don Cherry's pocket trumpet, a Telefunken U47 on Charlie's bass, and the drums were miked with a U47 as an overhead and a 77 over the hat and snare. We were recording live to mono and two-track at the same time. I liked this setup so much that I made sure I wrote it down, and I still have that setup sheet to this day. I would use it to record a lot of albums.

"The microphones were important, but just as important was getting the room to feel right. When they came in, they were well rehearsed. There were no music stands, no charts, Ornette didn't even count off — he'd just lower his horn and they'd all hit it exactly together, at exactly the same tempo. They could only rehearse at night — Ornette had a day job as an elevator operator down at the Bullock's Wilshire department store. He never did believe in that 'starving artist' routine.

"I would come out as they played, and 'cheat' the mics around a bit. But really, the sound came from their instruments and them balancing themselves. The music bounced off the walls and crept back in to the microphones. It was a great-sounding room and that was the way to get into the mix. The only other thing I did was to put a couple of carpets down on the the hard black asphalt tiles they used in studios back then. And 15 years later I was pretty much setting up the same way with Tom Waits."

Balancing Acts

Howe had tracked most of his pop records with the Wrecking Crew, the legendary LA session group which included Hal Blaine on drums, Joe Osborne on bass and PF Sloan on guitar. The way Howe had recorded them varied little from session to session during the 1960s. "In those days there was none of this 'Let me hear the kick drum, now the snare drum,'" he states. "If you listen to instruments individually, they don't sound the same as they will when they're all playing together, whether it's a drum kit or a rhythm section. When you have the musicians in the same room together, without headphones, they tend to balance themselves better than any engineer can."

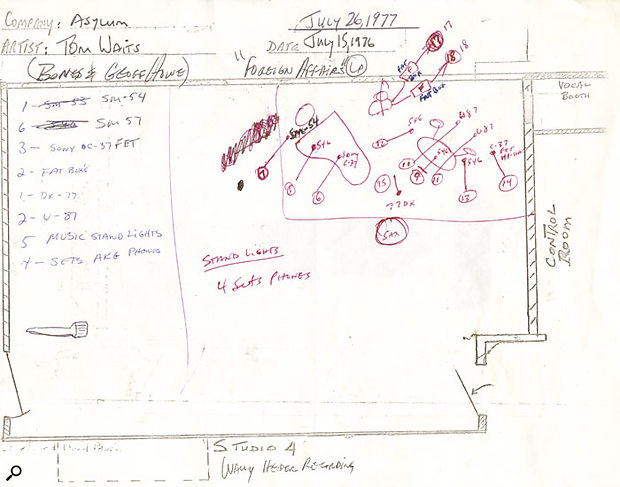

Bones Howe's original layout diagram for the live recording that would become Nighthawks At The Diner.

Bones Howe's original layout diagram for the live recording that would become Nighthawks At The Diner.

Howe's standard microphone set up on a four-track recording was Shure 546 mics on the snare, kick and hi-hat, as well as on the guitars, with a Sony C64 condenser microphone as an overhead, all recorded to mono. He would usually record bass and drums to one track, then put guitars and keyboards to another, non-adjacent track, leaving the intervening tracks for vocals and bouncing.

For Waits' and Howe's first collaboration, it seemed logical to move up to the larger track configurations that were quickly becoming popular, and Heart Of Saturday Night and Nighthawks At The Diner, the first two albums they made together, in 1974 and 1975 respectively, were done on the 3M 16-track deck at Wally Heider's Studio 3. Nighthawks was an especially interesting project.

"We did it as a live recording, which was unusual for an artist so new," says Howe. "Herb Cohen and I both had a sense that we needed to bring out the jazz in Waits more clearly. Tom was a great performer on stage — Herb had him out there opening solo with an acoustic guitar for the Mothers Of Invention, so that was a baptism under fire for anyone, having to yell back at the hecklers and do your show. I told Tom that he should use a piano instead, and he says back [and Howe can almost perfectly mimic Waits' trademark growl and inflections], 'There's never one up there!' So we started talking about where we could do an album that would have a live feel to it. We thought about clubs, but the well-known ones like the Troubadour were toilets in those days.

"Then I remembered that Barbra Streisand had made a record at the old Record Plant studios, when they were on 3rd Street near Cahuenga Boulevard. It's a mall now. There was a room there that she got an entire orchestra into. Back in those days they would just roll the consoles around to where they needed them. So Herb and I said let's see if we can put tables and chairs in there and get an audience in and record a show.

"I got Michael Melvoin on piano, and he was one of the greatest jazz arrangers ever; I had Jim Hughart on [upright] bass, Bill Goodwin on drums and Pete Christlieb on sax. It was a totally jazz rhythm section. Herb gave out tickets to all his friends, we set up a bar, put potato chips on the tables and we had a sell-out, two nights, two shows a night, July 30 and 31, 1975. I remember that the opening act was a stripper. Her name was Dewana and her husband was a taxi driver. So for her the band played bump-and-grind music — and there's no jazz player who has never played a strip joint, so they knew exactly what to do. But it put the room in exactly the right mood. Then Waits came out and sang 'Emotional Weather Report'. Then he turned around to face the band and read the classified section of the paper while they played. It was like Allen Ginsberg with a really, really good band."

Howe used a similar microphone setup as for previous sessions, although he had to make a few exchanges based on what Record Plant had available those nights. Electro-voice RE16s replaced the Shures he was used to, and Howe set up a Shure SM57 for Waits's vocal. "It was easy to use as a hand microphone," he says. "I also had a RE16 for him to use if he wanted." Howe ran the 3M 16-track deck at 15ips. "I knew the high end sounded better at 30ips, but I didn't like how it emasculated the overall sound and thinned out the low end. All the jazz records I recorded I did at 15ips. I actually went from 15ips on tape right up to the moment I started working in digital."

Small Changes

Despite the successful results Howe obtained with 16-track, the emerging jazz core to Waits' music pulled him back towards going direct to two-track for their later collaborations. "Jazz is more about getting a good take, not about having a lot of tracks to mix," Howe explains. "From then on, all the records I made with Tom were recorded directly to two tracks. We did run multitrack backups on Small Change and Foreign Affairs, though, and it was a good thing. On one of the tunes on Small Change Tom made a reference to [actress] Jayne Meadows and it was not something that was going to get past the legal department at Asylum. So I went back to the multitrack and had him re-record four bars of the vocal.

"We set up at Heider's for that record the same way I used to make jazz records in the 1950s," says Howe. "I wanted to take Tom back to that direction of making records, with an orchestra and Tom in the same room, all playing and singing together. I was never afraid of making a record where the musicians all breathed the same air. Leakage is not a problem. In fact, it's a good thing — it holds a record together. Where leakage is a problem is when you put the musicians in different corners of the room and use headphones. If you use the directional qualities of various microphones and set the players up so that they can see each other and hear each other without using headphones, you'll find that they will naturally tend to to balance themselves. What comes through the wires is more natural-sounding and three-dimensional. It's the room that adds that third dimension. You learn that in film scoring — the score is never fighting the dialogue. The element with the most presence is always up-front. In recording music, the room becomes like the score to the dialogue of the music.

"The choice of the room is critical, then, because it's like an instrument itself. There's one record that I didn't make that's a great example. Miles Davis's Round About Midnight was made at the old Columbia Studios on East 30th Street in New York City. [Author's note: I live across the street from where the studio, a former church building, stood. Several nights before it was to be razed to make room for an apartment building in the late 1980s, I took a crowbar and tried to pry off the bronze Columbia plaque on the front of the building to save it for posterity when a police car came by, causing me to abandon the effort. I don't know what became of it.] The sound of that studio was amazing. Jazz records tend to be dry-sounding, but that room had great natural echo. The musicians on that record were set up in a semicircle on stage, close together, and the sound of that record is the sound that came off that stage and bounced back into the microphones."

V Is For Vocals

Tom Waits's voice itself is a unique instrument. For that, Howe went back to his old standby, the classic RCA 77 DX ribbon mic. "The 77s have three cardioid settings," he explains. "V1 and V2 were different low-end cutoffs, and 'M' was for music recording. The V1 setting had a high cutoff, which made it good for radio announcing; the V2 position left a lot more low end in there and made it a great vocal microphone." The signal ran through a UREI 1176 compressor/limiter set with what Howe swears are the best parameter settings that can be configured on it for vocals: threshold/attack at 6, release at 7, and a 12:1 compression ratio. "Tom popped and spat a lot when he sang, so the 77 was perfect, because it's very hard to pop that microphone, so you didn't need a pop filter. Plus he liked to get right on the mic, so he would sit at the piano and I hung it from a boom so it would hang down in front of him. On some tracks we'd set it up directly in front of the band and he's stand in front of the drums and sing. On 'Step Right Up' you can almost hear him flipping pages of lyrics. He was always surrounded by the music and the records sound like it. We never used headphones. Never.

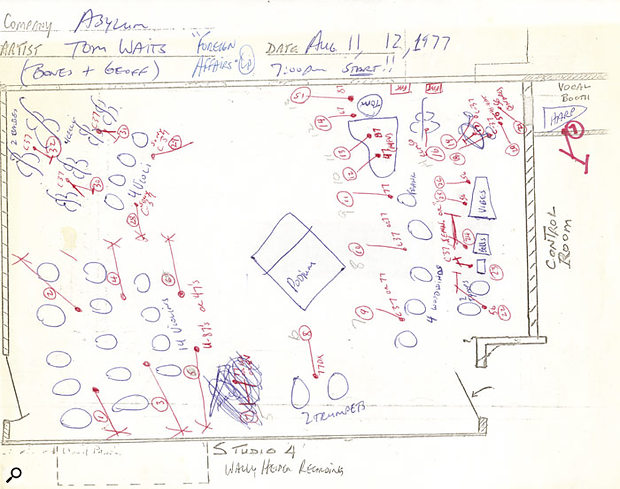

Bones Howe's layout diagrams for the Foreign Affairs sessions at Wally Heider Studio 4, showing the layout for the jazz band recordings.

Bones Howe's layout diagrams for the Foreign Affairs sessions at Wally Heider Studio 4, showing the layout for the jazz band recordings.

"We set Tom up in Heider's Studio 4 on the piano and built the orchestra around him. I just told the musicians to balance themselves, and they did. They were actually thrilled to be able to work like that. The 'cellos and the violas would come in and listen to a playback and then go out and adjust themselves accordingly. Each pass got better and better. I had two AKG microphones on the 'cellos and two Sennheisers on the violas, and whatever came out of the rhythm section got into those microphones, too, but it just made the whole thing sound better."

Diagram for the Foreign Affairs sessions at Wally Heider Studio 4 showing the layout used for the orchestral track recordings.

Diagram for the Foreign Affairs sessions at Wally Heider Studio 4 showing the layout used for the orchestral track recordings.

Understanding The Instrument

Bones Howe is emphatic that microphone techniques should involve an understanding of the instrument. "A good example is the French horn," he says. "Most people don't know that the French horn is not supposed to miked from the bell, which faces backwards. It faces that way for a reason — it's supposed to sound like it's coming up from a distance, from the back of the orchestra.

"One way to approach it [when it's not part of an orchestra] is to put a sheet of plywood behind it and place the microphone in the front to catch the reflected sound. Engineers tend to focus on what a microphone sounds like, but what people often miss is what the instrument is supposed to sound like. Microphones have only gotten better, so you really can't make a mistake if you know what the instrument is supposed to sound like. Not the console, not the tape. The instrument. Go out and listen to a symphony sometime. Just remember that you're there to capture the music, not figure out some great engineering miracle."

Towards The End

'Bones' Howe today.The collaboration between Tom Waits and Bones Howe lasted for three more albums, 1978's Blue Valentine, 1980's Heartattack And Vine and Bounced Checks in 1981, which was also Waits' last record for Asylum before he moved to Columbia Records. Towards the end of that period, the two shared an office on the Zoetrope Pictures lot in Hollywood, while Waits composed songs for Francis Ford Coppolla's film One From The Heart.

'Bones' Howe today.The collaboration between Tom Waits and Bones Howe lasted for three more albums, 1978's Blue Valentine, 1980's Heartattack And Vine and Bounced Checks in 1981, which was also Waits' last record for Asylum before he moved to Columbia Records. Towards the end of that period, the two shared an office on the Zoetrope Pictures lot in Hollywood, while Waits composed songs for Francis Ford Coppolla's film One From The Heart.

"I would come to the studio in tennis shoes and shirt and he would come in looking like he just got off Skid Row," Howe remembers. "I'd come in in the morning and do paperwork and Tom would drift in much later. He'd play me a few things on the piano. Then I'd leave and he'd stay into the night working, then go out to his usual haunts. He met his wife Kathleen there. She was a script reader and she showed up at the door one night and they met and he was smitten. He had been living in some awful motel on Santa Monica Boulevard and meeting her really turned his life around."

The record of the soundtrack broke some new ground for Waits; Howe recalls conducting an orchestra composed of car horns and creating percussion tracks by banging on hubcaps. The sounds prefigured Waits' later sonic experiments on records like Swordfish Trombones and Mule Variations. But it was the last record he would do with Howe. "He called me up and said 'Can we have a drink?'" Howe recalls. "He told me he realised one night that as he was writing a song, he found himself asking 'If I write this, will Bones like it?' I said to him that we were getting to be kind of like an old married couple. I said I don't want to be the reason that an artist can't create. It was time for him to find another producer. We shook hands and that was it. It was a great ride."