Despite having mastered sample manipulation and digital editing, Metronomy's Joseph Mount felt there was something missing — so he went cold turkey on computers...

Four albums into an eight-year career, Metronomy have grown from the bedroom project of singer, songwriter and producer Joseph Mount into a fully fledged band. The London-based five-piece enjoyed their commercial breakthrough this year with the Top 10-charting Love Letters. A blend of upbeat, retro-futuristic pop and artful ballads, it was recorded entirely analogue at Toe Rag in Hackney, East London, the studio whose previous clients famously include the White Stripes, Madness and Tame Impala.

For Joseph Mount, sonics aside, the all-analogue approach felt like a creative reboot after years of working in the digital domain. "In modern studios now,” he says, "everyone still has these big beautiful desks, but always looming at one side there's a computer monitor. I just felt that, even though you're going through all these great preamps, it's still ending up in this tower. And so I thought it'd be really nice to do a record and not still have that feeling that you leant on a computer.”

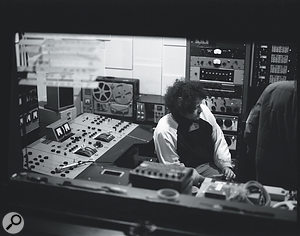

Metronomy's Joseph Mount at Toe Rag Studios.Photo: Tim EveHaving worked with engineer/mixer Ash Workman on Metronomy's previous album, 2011's The English Riviera, Mount brought him in as co-producer on Love Letters. "I was really excited by the project,” says Workman. "I suppose The English Riviera kind of set them up and got them a bit more attention, so off the back of that, it almost felt like the label were gonna let you do whatever you wanted with this one. But for Metronomy not to spend too long in the studio and just overcook something, which I think a lot of artists do, was a brave decision.”

Metronomy's Joseph Mount at Toe Rag Studios.Photo: Tim EveHaving worked with engineer/mixer Ash Workman on Metronomy's previous album, 2011's The English Riviera, Mount brought him in as co-producer on Love Letters. "I was really excited by the project,” says Workman. "I suppose The English Riviera kind of set them up and got them a bit more attention, so off the back of that, it almost felt like the label were gonna let you do whatever you wanted with this one. But for Metronomy not to spend too long in the studio and just overcook something, which I think a lot of artists do, was a brave decision.”

Time Away

Recorded in four bursts of week-long activity between Autumn 2012 and Summer 2013, the gaps between sessions on Love Letters allowed Mount and Workman time to reflect on the album's progress. "That's how I work best really… taking stuff away,” says Mount. "Because then you know exactly what you want to do when you go back for the next session. Also, creatively, I really wanted to experience making a record in a way that people used to experience making a record.”

Starting his musical life as a drummer in his native Totnes in Devon, Joseph Mount's first recording experience was in the home studio of a neighbour who performed as Paul McCartney in a Beatles tribute band. "He had a Fostex eight-track, a compressor and a little reverb box,” he remembers. "To me, the whole experience was amazing. It was like, 'Ooh, recording music is actually pretty exciting!'”

From this point, Mount began to get interested in dance music and bought himself a Zoom Sampletrak workstation before progressing to Apple's Logic. "I was using this other program called SoundEdit, this weird Macromedia thing where you could manipulate samples amazingly well. So I'd make these techy, glitchy little loops in that and work with them in Logic. At that point I just got into it very intensely.”

Moving to Brighton in 2002 to study, Mount began to DJ and continued working on his recordings, the result being the enigmatically titled debut Metronomy album Pip Paine (Pay The £5000 You Owe). "There was no real beginning point to that record,” Mount says. "Some of those tracks were written and recorded when I was 17 and some when I was 22. It was all done on this one Apple G3 computer, just with a mini-jack input, which gives it that inimitable sound [laughs].”

For that album's 2008 follow-up Nights Out, Mount grew more ambitious with his production values. "I bought one of those Edirol Firewire sound cards,” he says. "To me, suddenly everything sounded crystal-clear. Nights Out was recorded in the same way as the first album, but at that point I had a kind of studio in a conservatory at a friend's house in London.”

In The Double-edged Box

As Metronomy began to garner more attention, Mount was given the opportunity to make third album The English Riviera in a professional recording studio, namely The Smokehouse in London. "I felt like if I continued to make records in that home-studio way, it would have been kind of a forced decision,” he says. "'Cause everything was going well and obviously you've got more money to spend on recording. I guess all the time I was doing stuff on my computer and in a very self-sufficient way, I was imagining how I would do things in a studio and how I might record a drum kit and things like that.”

Although he enjoyed his first experience of working in a proper studio, something was still nagging away at Mount. "The first track we recorded for The English Riviera was 'We Broke Free', and after that, it felt like, 'OK, brilliant, this is really gonna work out.' But then I guess the funny thing is in that studio there's an amazing massive [Cadac E Type 66 channel] desk and all these beautiful microphones and great outboard… but you're still going into Pro Tools. So I was just lapsing back into how I would work at home: record a fraction of something and then loop it and muck around with that for hours on end. There was this kind of double-edged thing where it sounded brilliant, but I still felt a bit like it was all being done in the box.”

From their beginnings as a solo project Metronomy have evolved into a five-piece band, as here on stage at the Brixton Academy. From left: Oscar Cash, Joseph Mount, Anna Prior, Gbenga Adelekan and Gabriel Stebbing.Hence the decision to take an all-analogue approach on Love Letters. For Mount and Workman, it was something of a leap of faith, especially as the latter's only previous experience of recording to tape had been when assisting on sessions at RAK Studios during his apprenticeship years. "We went into Toe Rag and we had an assistant [Luke Oldfield],” Workman says, "but we were pretty much just thrown into it and it was like, 'Work out what you're doing and then make an album [laughs].' I was probably more intrigued than intimidated. In hindsight, I don't think I've ever tracked anything with as little EQ or compression. We hardly did anything, just because all the gear's amazing and it's a really good-sounding room.”

From their beginnings as a solo project Metronomy have evolved into a five-piece band, as here on stage at the Brixton Academy. From left: Oscar Cash, Joseph Mount, Anna Prior, Gbenga Adelekan and Gabriel Stebbing.Hence the decision to take an all-analogue approach on Love Letters. For Mount and Workman, it was something of a leap of faith, especially as the latter's only previous experience of recording to tape had been when assisting on sessions at RAK Studios during his apprenticeship years. "We went into Toe Rag and we had an assistant [Luke Oldfield],” Workman says, "but we were pretty much just thrown into it and it was like, 'Work out what you're doing and then make an album [laughs].' I was probably more intrigued than intimidated. In hindsight, I don't think I've ever tracked anything with as little EQ or compression. We hardly did anything, just because all the gear's amazing and it's a really good-sounding room.”

Mount says it soon became clear that Workman was going to very much deserve his co-production credit on the album. "So much of that kind of recording and production is based on technical ability,” he points out. "When you look at the desk and the setup in Toe Rag, it looks totally alien from anything else. But within a couple of days Ash knew exactly what was going on. We settled into it and it's such a pure way of working. Basically anything you record, you record, and once it's done you can kind of edit it in a way, but it's better to record it properly in the first place.”

Rags To Riches

The centrepiece of Toe Rag Studios at the time of the recording of Love Letters was owner Liam Watson's EMI REDD 17 console, At the time when Love Letters was recorded, Toe Rag Studios was based around an ex-Abbey Road EMI REDD desk. which was built in 1956 and originally installed at Abbey Road Studios (and which he's since sold on). For Love Letters, Mount and Workman recorded straight to Toe Rag's eight-track, one-inch Studer A80 tape recorder dating from 1970. Monitoring was done through the studio's custom-built monitors and Rogers LS3/5As, although Workman brought in his trusty Yamaha NS10s for additional reference.

At the time when Love Letters was recorded, Toe Rag Studios was based around an ex-Abbey Road EMI REDD desk. which was built in 1956 and originally installed at Abbey Road Studios (and which he's since sold on). For Love Letters, Mount and Workman recorded straight to Toe Rag's eight-track, one-inch Studer A80 tape recorder dating from 1970. Monitoring was done through the studio's custom-built monitors and Rogers LS3/5As, although Workman brought in his trusty Yamaha NS10s for additional reference.

Both Mount and Workman admit that while they were instantly thrilled with the sonic results, it took some time for their ears to adjust to them. "It's a funny one,” says Workman. "You're thrown into a room with unfamiliar monitoring and all their gear's good, so it takes you a while to work out what you prefer.”

"I don't think my ears are good enough to pick up on the nuances between certain preamps,” says Mount. "But certainly, when I took it home, everything was sounding amazing.”

While Toe Rag boasts a selection of custom compressors and vintage models built by Pye, Altec and Fairchild, Workman tended to use only tape compression during the tracking stages. "The main thing we did was get stuff right when we were recording it,” he says. "So if you want something more compressed, just hit it harder to tape, generally.”

In keeping with this more traditional approach, the general idea with initial takes of songs was to get as much as possible down live. "Every track on the record is basically live rhythm tracks, even with the drum machine-based ones,” says Mount. "With the more electronic ones, it would start with three of us in the room with the drum machine running and three synthesizers or organs or whatever. They probably ended up being some of the most straightforward [tracks], like 'Monstrous'. On 'Boy Racers', there's a sub-bass line and a kind of lead bass line which is all played live, and then the rest is all just little finishing touches. Something like 'The Upsetter' is basically recorded live apart from the chorus vocal, which is obviously tracked, and the guitar solo, which was added later.”

For the songs on which Metronomy drummer Anna Prior proved the rhythm track, Workman employed a pared-down microphone setup involving an AKG D12 on the kick drum, a Shure 545SD on the snare and two Calrec 600-series mics used as overheads. "That was it — literally four mics,” says Workman. "Up the EMI console and recorded in mono on one track of the eight-track tape machine.”  A minimalist four-mic setup was used to record Anna Prior's kit to a single track.

A minimalist four-mic setup was used to record Anna Prior's kit to a single track.

"I guess the great thing about Toe Rag,” says Mount, "is it has this live room which makes the drums sound good. So you rely on the fact that if they sound good in the room, they're gonna sound good on tape. Why bother fussing around with eight drum mics when you're gonna end up mixing it down into a place where you could have just used four?”

Spill & Separation

The fact that other instruments were being played in the room at the same time as the drums meant that there had to be screening involved. "The biggest track that we recorded live in terms of arrangement was the song 'Love Letters' itself,” says Workman. "For that we had drums, bass, a three-piece horn section, piano, vocals, tambourine and three backing vocalists. The studio's not huge but it's quite a dead room. The separation that you could get in there was really good, actually. We were screening off the drums and we'd screen off the amps accordingly, 'cause even the keyboards went through amps for all the tracks. Everything just got screened off as best as we could.”

"You try to point everything away from everything else as much as possible,” says Mount. "But it's one of those things where you're kind of mixing it as you're recording and you're trying to just make it sound good in the room. Whatever spill is reasonable… you can work with it really. The horns at the end of 'Love Letters' were done using one mic. It's that thing where you go, 'Oh, the trombone's a bit quiet,' and then you just speak into the room and say, 'Trombone, can you step a bit closer to the microphone, please?' So bloody simple.”

Metronomy bassist Olugbenga Adelekan's parts were recorded using Liam Watson's vintage Burns bass, through a variety of auto-wah and chorus effects, depending on the track. "On 'Never Wanted',” says Mount, "I've got this pitch-shifter pedal which I've ended up using as a chorus instead. You detune it and you get this quite strong chorus effect.”

Guitar-wise, Mount played his time-served Stratocaster, in conjunction with Watson's old Selmer and Gretsch amps. "You go into somewhere like Toe Rag,” Mount laughs, "and you realise that whatever he's got is probably better than the Fender Twin you're going to bring in. Liam has thought about everything a lot more than I have.”

Feel Versus Fluffs

When it came to recording vocals, Mount and Workman felt that the process benefitted from the limited options available to them when recording to tape. "With this record, we didn't comp anything really,” says Mount. "I guess my attitude was if Metronomy is gonna take what they're doing into a tape studio, then why are you gonna start messing around comping vocals? Because if you want to do that, the best way to do it is in Pro Tools. So we would just go for takes, basically. And there might be a few little bits of punching in, but with eight tracks, you're never gonna be in a position where you're comping from three tracks or whatever. It's just impossible. So in a way that ended up becoming more like the attitude: you have to decide whether your idea of the best take is the one with the best feel or technically the best take. So that's how we ended up working — picking the take with the best feel, even if there were little errors or fluffs.”

The vocals were recorded using Toe Rag's AKG C12A. "It looks like a 414 but it's an older valve mic,” says Workman. "I just thought it suited Joe's voice. In terms of vocals, we didn't keep two takes of anything. We'd do a take and if we weren't happy with it, we'd just go over it. For us, that was one of the coolest uses of the tape machine, I guess. As great as it obviously sounds. I was listening to the plug-in emulations they do now, but you don't get any mistakes with those type of things and that was the true beauty of it.”

"Vocals were the only thing that felt like they needed any compression in the mix generally,” says Workman, "unless it was something to be used as an effect.” The main compressor used on Mount's vocals was the Audio & Design F700.

Accidental Outros

In fact, happy tape accidents were to figure in some of the musical structures on Love Letters. "We'd record a part on the track, then we'd decide we didn't like it,” says Workman, "so we'd replace it with something else. But you press Stop just before the outro, and then that part that you didn't like is all of a sudden only in for the outro, and it comes out of absolutely nowhere. So some of the arrangements are influenced by our mistakes using the tape machine.”

Keeping it analogue, even the field-recorded swimming-pool splashes that feature in 'The Most Immaculate Haircut' were captured on cassette on Mount's father's old Sony Professional Walkman. "By this point I got the idea into my head that this record was not gonna be digital in any way,” he says. "So I went on this first family holiday with my girlfriend and our baby, and I had an amazing week in Tuscany. I knew that I wanted to get a swimming-pool splash and so we were always waking up really early and I would just spend a little bit of time recording my girlfriend diving into the swimming pool.”

Despite the wealth of vintage effects available at Toe Rag, Workman tended to use very few of them. "They have the EMT 140 plate, which we used,” he says. "Apart from that, they have an old Vortexion tape machine that we used for auto-double tracking and tape delays. But my favourite effect that we used was just backing off the mic when recording vocals. On 'I'm Aquarius', really the small bit of room that is around the vocal is just because Joe was standing about three metres away from the microphone.”

In keeping with this attitude, Workman tended to keep the mixes on Love Letters fairly dry. "I suppose there's quite an obvious lack of effects on things on the album. That was something Joe and I experimented with on the previous album but then actually just took a step further with this one. It's funny because I think when you start using effects, it kind of leads to you using a lot more of them. Whereas if you mix a track that's really dry, as soon as you put an effect on anything, you're like, 'Urgh, no no no, I don't like that.' If you have a really wet-sounding drum kit, everything else needs to be wet for it to all glue together. If you have a really dry kit, everything else can be dry.”

For The Half That Cares

Originally the plan was to mix the album at Workman's studio, where he's recently installed an SSL G-series desk. The pair were having trouble finding a Studer A80 eight-track machine, however, and ultimately decided that dumping the masters into Pro Tools at this stage would be defeating the analogue purpose of the project. "The idea of bringing eight tracks onto my 48-channel desk seemed overkill,” Workman says.

"I was kind of saying, 'I really think it would be such a cop-out at this point to digitise anything,'” says Mount. "Half the world will never care, but I thought just for our own achievement, it would be so nice to get this to vinyl without it ever having been digitised. So I said, 'We'll do it in Toe Rag and make it sound good.'”

Initially, while the pair thought they might need to use some digital effects, notably the Eventide H3000, the results didn't sit in the tracks. "We did these mixes and took them away and it was like, 'Oh my God, they sound mad!'” says Mount. "Once we got our heads around the fact that you shouldn't mess around too much with what you've got, it became very enjoyable and quite easy really.”

Out of all the tracks, 'Love Letters' was to prove the toughest to mix. "I suppose it was quite a pressure song because it's the lead track off the album,” Workman says. "But also in tracking that was the one that got hit hardest to tape. Maybe even too hard. It was still unfamiliar territory for us, so it was just maybe that slight bit too crunchy, whereby you actually lose a bit of dynamic. It eats up your space quite a lot. That one was the toughest, but it was also the biggest arrangement. With 'I'm Aquarius', we did a demo mix to listen to in my studio before we'd even finished adding the backing vocals. Then we went back and mixed it again, but it was like, 'How do we make it sound like the first mix that we didn't care about?' So that was probably the simplest.”

Quickly the pair developed a modus operandi. "We'd do mixes in Toe Rag, then we'd run over to my mix room to have a listen to them,” says Workman. "I'd kind of be surprised by our own mixes, which was actually quite cool. I'd think, 'Oh wow, I've never mixed anything that loud in comparison to everything else.' I don't think it would work for every project, but seeing as they were such simple tracks, nothing we did really felt wrong, unless a vocal was obviously way too loud or something. It kind of allowed us to be a lot more creative.”

Mixing To Tape

Mixing down onto Toe Rag's Studer A80 quarter-inch two-track also added another layer of creativity. "There were a few little tape edits,” says Mount. "We chopped a section out of 'Boy Racers' and we basically sequenced the album on tape, with the gaps done with leader tape, as it was gonna be cut onto a record. So when it came to mastering it was literally like, 'Record tape one and that's side A, tape two Side B.'”

At the same time, Workman was faced for the first time with factoring in the added compression when mixing to tape. "I suppose coming from mainly working digitally, that it was a new thing to settle on a mix and then have it come back sounding different. That was an additional stage in the whole process that I hadn't experienced before. In the same way, there were tracks we mixed towards the end where we maybe did it the other way around and they benefitted from going a bit harder to the tape machine. But everything is so well-maintained there by Liam. Everything works perfectly. You don't have to worry about any kind of mechanical fault and nothing's noisy. It's a particularly slick operation.”

In the end, while the making of Love Letters was a massively enjoyable and productive experience for Joseph Mount, he admits that the analogue approach isn't one that he wants to immediately repeat for the next Metronomy album. "I'm not at all anti-digital,” he stresses. "The reason I wanted to do it was to have this sense of making something, which you can't really get in the same way with a computer. And working like that taught me so much. But what it's taught me isn't anything that can only exclusively be done on tape. You can apply it to using Logic or Pro Tools or whatever. I think the next Metronomy record will most certainly not be recorded onto an eight-track tape machine. But if I'm ever working with other people or producing, I know what it offers as an option.

"I guess the thing with Love Letters is that it's not the record I was trying to make sound the most polished,” he concludes. "I wasn't going into Toe Rag and recording to eight-track to make a really slick-sounding record. But you can do that. If that's what you want to do, you can make that eight-track sound incredible. But I think it's heartening to know that you can do anything you want to do in that amount of physical space.”

Music Without MIDI

Although he has used soft synths in the past, Joseph Mount is very proud of the fact that all the keyboard parts on Love Letters were recorded live. "I've never really got into MIDI,” he says. Metronomy used a wide array of synths including two Roland Juno 60s and a Juno 106, and a Siel Orchestra 2. The workhorse, however, was Mount's Yamaha EX2. "It's another one of these things that I bought and then felt I needed to get my money's worth out of,” he says. "It's this big church-organ-type thing that sounds amazing and has the same kind of circuitry as a CS80. It has a limited synthesizer section, but it's so warm. Everything on 'I'm Aquarius' is pretty much played on that. I also bought this Baldwin Electric Harpsichord which has been kind of relegated to just the intro of 'Monstrous'. Originally it was played on the harpsichord, but it sounded a bit too baroque.”

The distinctive piano sound on the title track of 'Love Letters' was created by double-tracking Toe Rag's Kemble upright. "One thing that I wanted to do when I knew I was going to record in a tape studio was to get that chorus-y piano effect,” says Mount. "The double track was varisped very slightly slower, so it has this kind of ELO or honky-tonk effect. It's lovely.”

Elsewhere, a big part of Metronomy's sound on Love Letters is the warm pulse of old beatboxes. "It's funny, people keep referring to these crappy, boxy drum machines being on the record, and I feel a bit hard done by, because they weren't necessarily the cheapest things in the world,” Mount laughs. "But there's various things I picked up.” Chief amongst the drum machines used were Mount's Ace Tone FR3, a Roland TR808 borrowed from Arctic Monkeys/Haim producer James Ford, and Mount's most recent acquisition, an Eko ComputeRhythm from the early '70s, these days valued at around £5000.

"It was a crazy eBay purchase,” Mount laughs. "I felt like I had to use it as much as I could because I'd spent so much money on it. It's a very beautiful drum machine, like a physical version of the Reason program: it's got these lights that flash along and you punch in the rhythm. Sonically it's not incredible, but that's on 'The Upsetter' and 'Monstrous', so I got my money's worth.”