Great backing vocals can be essential if you want to turn a promising track into a superb one — so find out how to get them right every time.

A strong lead vocal is the star attraction on most hit records, but it's unusual for it not to be aided and abetted by a supporting cast of double-tracks, harmony lines and other backing vocals (BVs). Far from being minor details to be thrown into the mix at the last minute, great BVs contribute hugely to the effectiveness of a tune, by adding emotion, sustaining interest, and delivering that vital punch to choruses and hooks. It makes sense, then, to lavish plenty of care and attention on your BVs.

Getting Started

A lead vocal will ideally be delivered as expressively and freely as possible, while respecting the melody, but this isn't usually the case for BVs. These supporting parts need to follow a pre-determined outline, and so require discipline from both producer and vocalist. This is especially true in the case of multiple-part harmonies, which have to be 'composed' to some extent, then tracked accurately, and then edited to varying degrees. Indeed, while you'll always get better results if the parts have been well rehearsed, when it comes to modern pop, dance and urban genres, editing is an equally (if not more) important part of the BV production process. These styles demand ultra-tight performances, with no ragged edges, so be prepared to put in some serious hours in front of a screen, and get to know your DAW's editing shortcuts to make the process as painless as possible!

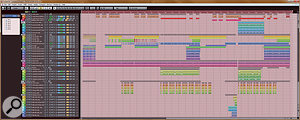

It's very common to double-track, and even quadruple-track parts, which means a vocal arrangment with harmony parts — such as the one pictured here — requires thorough planning before you start recording!There are no hard-and-fast rules that govern what part to use where, but knowing what type of BV you want before you hit 'record' is incredibly helpful: the choice will determine the number of tracks required and the amount of time you're likely to need for the job, not to mention how you brief any singers you're working with. A simple harmony may take less than a minute to record, whereas editing a multi-part section can turn into a solid day's work. With this in mind, spend plenty of time listening in detail to recent hits or your favourite classic productions, so that you develop a good understanding of the types of BV that appeal to you, and an idea of which sort of tracks the variations usually suit best.

It's very common to double-track, and even quadruple-track parts, which means a vocal arrangment with harmony parts — such as the one pictured here — requires thorough planning before you start recording!There are no hard-and-fast rules that govern what part to use where, but knowing what type of BV you want before you hit 'record' is incredibly helpful: the choice will determine the number of tracks required and the amount of time you're likely to need for the job, not to mention how you brief any singers you're working with. A simple harmony may take less than a minute to record, whereas editing a multi-part section can turn into a solid day's work. With this in mind, spend plenty of time listening in detail to recent hits or your favourite classic productions, so that you develop a good understanding of the types of BV that appeal to you, and an idea of which sort of tracks the variations usually suit best.

Tracking

For basic BV tracking, the usual rules of vocal recording apply: make sure you create a decent headphone mix for the vocalist, to aid them in their pitching; pay attention to the sound of the room, and the mic, making sure you minimise unwanted room reflections, avoid boxiness or excessive proximity effect, and so on. Your aim is to emerge from the session with good performances recorded cleanly, so that you have usable tracks to work with when it comes to the mix.

To write, record and edit good backing vocals, you need to know what sort of arrangement and sound will work with a given track — so spend some time trawling through your music collection, and contemporary pop music compilations, to develop a feel for which styles you like, and which will suit the material you're working on.

To write, record and edit good backing vocals, you need to know what sort of arrangement and sound will work with a given track — so spend some time trawling through your music collection, and contemporary pop music compilations, to develop a feel for which styles you like, and which will suit the material you're working on.

We've run plenty of features on vocal recording over the years, so rather than revisiting the basics, I've listed some useful articles in a 'Further Reading' box. Most assume the typical modern scenario of a producer with a DAW working with one singer, and one tip I'd add specifically for backing vocals in pop styles is that, even when working with two or more vocalists, it can be a good idea to stick with a single mic; there's often little other than phase issues to be gained from using more. While you might choose to use a stereo configuration to capture an ensemble or choir, large numbers of vocalists can often be placed around a single omni-pattern mic. All you need to do is to make sure you adjust each singer's distance from the mic to achieve the best balance between them all. In short, I recommend keeping things simple where you can while tracking, as it will get complicated enough later on!

Double-tracking

As distinct from the sort of doubling that can be achieved via software delays or dedicated hardware, a proper double-track comprises two note-for-note performances, one duplicating the other. Whether or not a double-track is actually a 'backing vocal' is debatable (it's not a distinct musical part), but as it's not a simple lead-vocal recording, let's look at it anyway.

Because double-tracking enhances tonality while blurring the rough edges of a less-than-perfect performance, it's often a useful technique to deploy on mediocre or unconfident singers as a flattering effect. The (big) down side is that it can also reduce the immediacy and intimacy of a vocal part, especially if it's a good one, so tread with care. Creating a double-track is easily accomplished by getting the singer to accompany their own lead vocal, duplicating any nuances wherever possible. Often, though, the process can be even simpler: if more than one take of the lead vocal has been recorded, with a little luck and a bit of editing an unused take can function as the double. But if the vocal is up-front and exposed, or if the main part features a once-in-a-lifetime performance, additional takes to duplicate it and/or some serious editing will be required.

Double-track Octaves

A variation on the double track is to have a duplicate vocal sung an octave up or down, subjectively adding 'weight' or 'air' to the main vocal. Typically, a low-octave double will end up being mixed dry and close to the lead, whereas octave-up tracks usually benefit from a good splash of reverb. Deciding whether to use either is a musical decision, and it really requires that you commit to it, as once you've started it's hard to change your mind. Beloved of U2's Bono among others, octave tracks can help create a 'vocal sound', and they're best used on whole sections, such as a complete verse (or even the whole song), rather than on individual lines for effect.

Unfortunately, especially when going for a falsetto double, it's entirely possible to run into situations where the verse sounds fantastic, but the chorus is simply beyond the singer's range. In such cases, a useful compromise is to keep the fantastic verses, and maintain the high-octave melodic energy in the choruses courtesy of a guitar or keyboard part, while the singer drops to their 'normal' register and confidently hammers home the chorus. When the high vocal returns in the next verse, the contrast should be pleasing.

Single Harmony Lines

The simplest harmony line can be a thing of great beauty, with its timely arrival helping to sustain interest in a tune, by adding richness, poignancy and emotion. If your musical act is blessed with two or more exceptional vocal talents you may have entire songs sung in harmony, as in the Simon & Garfunkel classic 'Sound of Silence', or numerous Beatles or Crosby, Stills & Nash tunes, for example. But in most modern pop music, harmonies are used to highlight particular lines, and they don't usually appear until the melody has been firmly established. On verses especially, in order not to distract from the main vocal and overload the track, single harmony lines are usually best produced as just that: a single line, recorded once (or twice at most); there's rarely any need for the thickening effects of multi-tracking.

Multi-part Harmonies

It may not be a vocalist, but a synth or guitar part can be your secret weapon: try using them to take over a high double or harmony part where the desired part strays above a singer's range, or simply to divert attention from a vocal part ending — so that it can come back in later to help you build your track.Recording multiple parts requires additional application from both producer and vocalist. I recommend that you start by getting a perfect take of the first harmony, then moving on to the next one up, then third, fifth, seventh and so on. Then finish with any low harmonies beneath the lead, if they're required. You can end up with a lot of parts in this way so, to avoid getting lost, take notes: good old-fashioned pen and paper can be used to cross off each part as it's done, and completed region recordings can be colour-coded in the DAW for easy reference.

It may not be a vocalist, but a synth or guitar part can be your secret weapon: try using them to take over a high double or harmony part where the desired part strays above a singer's range, or simply to divert attention from a vocal part ending — so that it can come back in later to help you build your track.Recording multiple parts requires additional application from both producer and vocalist. I recommend that you start by getting a perfect take of the first harmony, then moving on to the next one up, then third, fifth, seventh and so on. Then finish with any low harmonies beneath the lead, if they're required. You can end up with a lot of parts in this way so, to avoid getting lost, take notes: good old-fashioned pen and paper can be used to cross off each part as it's done, and completed region recordings can be colour-coded in the DAW for easy reference.

Such book-keeping methods help to ensure that you complete individual sections, but they're also an aid to maintaining a compositional overview of a complete song. If, for example, you have a spectacular three-part harmony on the fifth line of the first verse, chances are you'll need something similar in the same place on later verses. Again, one or two tracks per part should be sufficient: if the harmonies are nicely constructed and well-performed, it's usually pleasing for the listener to be able to pick out the individual voices making their contribution, so the blurring and rounding of many layers can be counter-productive.

Crossing Lines

Lines that flow in between or through the melody (usually from above to below but not necessarily so) can help to join song sections together by reducing 'blockiness,' as in transitions from verse to bridge or chorus, for example. They can also be very satisfying from a creative, compositional point of view, as they add a welcome dash of complexity to an otherwise simple arrangement.

Some basic musical chops are helpful here, and it's always worth picking out the notes on a piano or guitar to ensure that as the harmony line passes through the melody no unison notes are created. "Why avoid unison notes if the part works?” I hear you ask. It's simply because they can cause an unpleasant jump in level at the crossover point, due to the summing of the amplitudes of the two parts when they're singing the same note. It's not impossible to deal with at mixdown, but usually there's at least one other note that works equally well or better and saves you the bother.

Another pitfall to watch out for is lyrical overload, especially if the words in the harmony line(s) are different to those used in the melody. Take care to avoid a confusing collision of lyrics, which can be distracting and disorientating for the listener: writers and producers will 'know' the words being sung, but the listener doesn't have that advantage. So make sure it sounds right, without clashes, no matter how clever the lyrics may be.

The Chorus Block

Nothing beats the massed ranks of a block of multi-tracked BVs to complete the high point of a song, whether that be a chorus or an anthemic outro. In many a pop chorus, the backing will join with the lead vocal as an equal, and even take over the role completely, allowing the lead singer to improvise and ad lib. In order to achieve this effect, the job of singer and engineer alike is to ensure that the chorus harmonies are powerfully sung and rhythmically tight.

Additionally, consider the sheer amount of tracking that's necessary to achieve the wide stereo spread typical of modern pop vocals. Two similar vocal tracks placed in the same location in the stereo field will clearly exhibit the effects of double-tracking, but once panned hard left and hard right, you'll lose much, if not all, of that effect: each is now a single voice coming from a single speaker. In other words, in order to create a truly wide multi-tracked vocal, each part needs to be performed at least four times — twice each for left and right. (And having done that, you may well find that three or four times is better!)

Even if you wish to place different tracks at less extreme pan positions, you'll have to record each more than once to get the lush sound you can hear on the best productions. The rich, smoothing effect of multitracking can be highly addictive, especially on the ubiquitous 'oooh' and 'aaaaah' parts, so a three-part harmony will usually eat up a lot of DAW tracks very quickly. Unless you're organised, this soon makes it difficult to navigate your project, so keep on top of things by designating a bus or group track for each harmony part, and once recorded, assign each track appropriately. The same goes when mixing: if you're supplied with a chaotic mess of backing vocal harmonies, don't even attempt to tweak the fader levels until you've grouped things together!