We explore some of the most common causes of mix failure we've tackled in our monthly Mix Rescue column. Banish these demons and you're most of the way to a devilishly good mix!

Over the years, I've listened to piles and piles of amateur mixes from home studios, including thousands of productions submitted by SOS readers to Mix Rescue, Studio SOS, Demo Doctor (the predecessor of the current Playback column), and the My Sound Files section of the SOS forum. On top of that lot, I've heard almost as many mixes again from students and teachers working in small college studios. What I've learnt from all these mixes is that some problems crop up much more often than others.

What really crystalised this opinion for me recently was listening to over 100 mixes of the same raw multitrack files in order to adjudicate a recent 'mix‑off' contest. Because everyone had worked from identical source material, the submissions clearly demonstrated that the same issues were undermining people's final results time and time again.

The purpose of this article, then, is to reveal the most common of these recurring mix nightmares — and thereby help you to avoid them in your own projects. There's only so much that text can tell you about mixing, though, so to make things clearer I'm going to refer to the aforementioned competition mixes by way of real‑world audio illustration — see the 'One Song, 100 Mixes!' box for details of where you can listen to them. I've actually just completed my own mix of that track, which will appear as a forthcoming Mix Rescue feature — so watch this space if you're keen to know how I approached the track myself! I've also trawled through various articles in the SOS archives at www.soundonsound.com to create an on-line list of useful further reading, including several past Mix Rescues, which offer copious example files, as well as links to useful software resources. See the 'Further Reading' box for details. But now, without further ado, let's reveal and rectify the most common rookie mistakes...

1: Dodgy Timing/Tuning

Here's the waveform from a live drummer's kick‑drum mic. Even though the part was recorded to a click track, you can see that it naturally (and desirably!) deviates a little from the metric grid.

Here's the waveform from a live drummer's kick‑drum mic. Even though the part was recorded to a click track, you can see that it naturally (and desirably!) deviates a little from the metric grid.

This is probably the single most common weakness of home‑brew mixes. Like it or not, the public these days are used to unnaturally tight tuning and timing. A genuinely laid‑back feel is one thing, but sloppiness in this department is one of the quickest ways to make your mix sound like a demo. Unfortunately, a good 90 percent of the amateur mixes I hear fall at this hurdle, simply because too little care has been taken over such matters during rehearsals, tracking, overdubbing, and editing. Furthermore, of those home recordists who do actually apply some serious elbow grease here at the edit/mix stage, only a small proportion actually end up with really decent results, simply because it's so easy to mishandle the available tools.

Now, I realise that some people take a pretty strong stance against the use of corrective measures like these, and probably the most frequent complaint is that such tactics kill the emotion in the music. My response is that good corrective processing shouldn't do that, as it will only target the inaccuracies that undermine the music, while leaving alone those that support it. To put it another way: just because a few nutters go round stabbing people, it doesn't mean we should ban knives entirely! Clearly, you need to be careful not to push your corrective mix procedures too far, but my own experience suggests that the vast majority of home‑brew productions are in absolutely no danger of straying over that line. Here are some tips and tricks to help you get things right:

Here you can see a small section of the lead vocal part from SOS January 2011's Mix Rescue mix, in Celemony's Melodyne Editor pitch/time‑processing software. Although notes look out of tune, you can listen to the remix to confirm that they don't sound that way in the context of the track.Timing correction isn't about quantising everything to your sequencer's bars‑and‑beats grid. It's more about tightening up disagreements between the available parts in your arrangement. As such, your drum waveforms are usually a better visual guide for editing purposes than software bar/beat lines.Fully automatic pitch‑correction will almost never achieve an acceptable combination of tuning accuracy and musicality, so be prepared to spend some time manually finessing the action of any pitch‑correction utilities you choose to employ.For timing purposes, the end‑point of a note can be almost important as where it begins, especially when you're dealing with bass lines.Whether you're adjusting timing or tuning, avoid the powerful temptation to trust your eyes over your ears. Although looking at software waveforms and pitch displays can help speed up corrective editing, it's not at all uncommon for them to show some notes as 'correct' even when they're still audibly awry, and vice versa.It's particularly easy to lose perspective while editing timing and tuning, so take frequent breaks and make sure to listen to the track at least once all the way through (preferably without looking at your computer screen) before signing off your edits.

Here you can see a small section of the lead vocal part from SOS January 2011's Mix Rescue mix, in Celemony's Melodyne Editor pitch/time‑processing software. Although notes look out of tune, you can listen to the remix to confirm that they don't sound that way in the context of the track.Timing correction isn't about quantising everything to your sequencer's bars‑and‑beats grid. It's more about tightening up disagreements between the available parts in your arrangement. As such, your drum waveforms are usually a better visual guide for editing purposes than software bar/beat lines.Fully automatic pitch‑correction will almost never achieve an acceptable combination of tuning accuracy and musicality, so be prepared to spend some time manually finessing the action of any pitch‑correction utilities you choose to employ.For timing purposes, the end‑point of a note can be almost important as where it begins, especially when you're dealing with bass lines.Whether you're adjusting timing or tuning, avoid the powerful temptation to trust your eyes over your ears. Although looking at software waveforms and pitch displays can help speed up corrective editing, it's not at all uncommon for them to show some notes as 'correct' even when they're still audibly awry, and vice versa.It's particularly easy to lose perspective while editing timing and tuning, so take frequent breaks and make sure to listen to the track at least once all the way through (preferably without looking at your computer screen) before signing off your edits.

Example Mixes: Although a majority of the contest submissions leave tuning pretty much untouched, there are nonetheless some mixes (17, 20 and 39, for instance) that make a pretty respectable job of it. None of the mixes quite tightens the timing enough for me, though, which underlines how few small‑studio mix engineers realise the importance of this, for rock productions in particular.

2: Mix Tonality Misjudgements

Don't compare the overall tonality of different mixes at just one volume level. Give that monitor level control some exercise to get a more informed perspective.

Don't compare the overall tonality of different mixes at just one volume level. Give that monitor level control some exercise to get a more informed perspective. Plug‑ins such as Melda's MAutoEqualizer can measure the overall frequency response of your whole mix, and then compare it with that of any commercial release. Although you must always carefully evaluate the results of any such software analysis by ear, it can be a useful reality check.

Plug‑ins such as Melda's MAutoEqualizer can measure the overall frequency response of your whole mix, and then compare it with that of any commercial release. Although you must always carefully evaluate the results of any such software analysis by ear, it can be a useful reality check.

Anyone who's ever had their portable music player in shuffle mode should be aware that there's no standardised quantity of lows, mids, or highs in a commercial mix. That said, though, it's rarely sensible to endow your own production with an overall tonality that makes it feel out of place alongside comparable commercial tracks. As such, it's as well to do at least some comparative checks against stylistically similar releases during the mixing stage to avoid any obvious tonal mismatch, even if you have the luxury of a good mastering engineer to refine this aspect of the sonics post‑mixdown — you don't really want them applying drastic master EQ, simply because it will almost certainly upset your carefully crafted instrument balances.

Although I don't consider what I've just written to be tremendously contentious, it still surprises me how often home mixers allow overall tonality problems to stymie their efforts. To some degree I suppose it's understandable, given that both the vagaries of low‑budget monitoring and the real‑time adaptability of the human hearing system can heavily disguise a skewed frequency response, preventing it from reaching the forefront of your attention. Those seem like flimsy excuses to me when there are so many cheap and easy remedies on hand. Here are some useful pointers:

- Import several commercial mixes into a fresh project in your sequencer alongside a stereo bounce‑down of your own mix, and then switch between them instantaneously using the track solo buttons, so that you throw the tonal differences into starkest relief. Use the track faders to compensate for loudness differences between the tracks.

- Compare mixes on more than one listening system, if possible, and at different playback volumes, to lay bare as many different tonal facets as possible.

- Get hold of some kind of high‑resolution frequency-analysis tool to provide you with extra information about the frequency spectrum. Voxengo's SPAN provides decent free spectrum-analysis in plug‑in form, but if you've got any budget available at all, I'd certainly recommend investigating some of the more sophisticated tools that allow you to capture a tonal fingerprint averaged over the whole track — tools like the Melda MAutoEqualiser and Voxengo Curve EQ plug‑ins, or the off‑line Har-Bal software. Whatever any software tells you, though, be very wary if it contradicts the evidence of your own ears.

- Fixing a broad tonal imbalance in your mix can be as simple as inserting a high‑quality EQ plug‑in on your master channel. However, if you find yourself using more than three or four EQ bands, applying more than 3‑4dB of gain per band, or using narrow filters (Q>1), it's more than likely that your per‑channel EQ settings need some reassessment too.

Example Mixes: There is a huge tonal range to the competition mixes, despite the band having provided a detailed list of commercial reference productions. Compare the HF crispiness of mix 43 with the stifled highs of mixes 35 or 58, for example, or line up the powerful low end of mix 32 with the slimline low frequencies in mixes 23 and 29. Mixes such as 19 and 43 have over-prominent mid-range, while others, such as 12 and 48, are recessed in that region. All that said, it's worth pointing out that even the mixes that feel most successful to me in this respect (mixes 04, 20, 31, 61 and 63, for instance) there is still a good degree of tonal variation — every mix doesn't have to sound exactly the same to tick this particular box, and there's certainly some room for personal preference.

3: Phase Misalignment

If you use more than one mic to record any instrument, there's always the danger that minute time‑delays between the recorded signals will cause a type of frequency cancellation called comb‑filtering when the mics are combined at mixdown. Similar difficulties can also arise when combining mics with DI signals; when summing stereo mic pairs or send effects to mono; and when triggering samples alongside live parts. Most home‑studio folk underestimate the importance of dealing with phase mismatches, leading to mixes with hollowed‑out sounds and poor mono compatibility. However, there are now so many ways to address phase issues in a typical MIDI + Audio sequencer — fine delays, audio editing, polarity inversion, all‑pass filtering, phase rotation — that there's really no need for comb‑filtering to rain on your parade. For better results, try these tools and techniques:

- Listening to your mix in mono is a quick way to check if any stereo signal in your mix harbours phase problems. Although summing the left and right stereo channels of a mix will always cause a certain degree of tonal change, you need to be on the lookout for any dramatic alterations that stand to make a nonsense of your mix balance. If you do find phase gremlins, try applying phase‑adjustment techniques to one side of the offending stereo channel to improve the situation.

The simple act of switching your monitoring to mono can reveal all sorts of hidden phase conflicts in a stereo mix.

The simple act of switching your monitoring to mono can reveal all sorts of hidden phase conflicts in a stereo mix. - There are a number of dedicated phase‑adjustment plug‑ins worth investigating, including commercial products such as Audiocation's Phase, Voxengo's PHA‑979 or Littlelabs' IBP Workstation (for the UAD2 platform), as well as freeware such as Betabugs' Phasebug and Variety Of Sound's new preFIX.

- Be careful when layering several bass parts or low drum sounds within a single arrangement. Allowing such layers to slip in and out of phase with each other is a recipe for frustration, because it'll cause the combined tone to change sporadically throughout the timeline in a way that's almost impossible to fix with normal mix processing.

Example Mixes: The multi‑miked guitar parts in the competition multitracks caught out a lot of contestants, who chose to pan the individual mic signals across the stereo field without phase‑aligning them first — compare mixes 36, 43, 58 and 59 in stereo and mono, for example, to hear what I mean. Phase cancellation between the left and right overhead mics caused mono‑compatibility problems too, as in mixes 33, 56 and 61.

4: Mix Mud

There are several great plug-ins for adjusting phase relationships, so there's really no excuse for letting comb filtering wreck your sonics

There are several great plug-ins for adjusting phase relationships, so there's really no excuse for letting comb filtering wreck your sonics

The lower half of the mix is frequently something of a battle zone. Pretty much any track can contribute low‑end energy, but unless you're careful about which tracks you allow through in this range, it's very easy to end up with a gloopy‑sounding mess that blurs the definition of your bass parts. The widespread use of close‑miking techniques is partly to blame for this common problem, because of the artificial bass boost (called the 'proximity effect') that most directional microphones impose under such circumstances. However, many synthetic sounds and samples often contain much more LF than is actually required in a mix, too, so programmed arrangements are no safer from this pitfall than live recordings. Try some of these tricks and see if things improve:

- Apply high‑pass filtering to any instrument that doesn't actually require low end for musical reasons. This will ensure that DC noise, traffic rumble, mic‑handling noise, and any other low‑octave rubbish doesn't interfere with your main bass parts.

- When setting filter frequencies, make sure to listen within the context of the mix. You might be surprised by how far up the spectrum you can go before the sound starts to lose warmth in context. Be careful with percussive sounds, though, as these can lose subjective punch well before overall tone seems to change.

- Try to funnel your different bass instruments into different frequency regions using pitch and EQ controls. The more these parts have to fight for the same space, the trickier it'll be to avoid murkiness.

- Be wary of delay or reverb effects that take ages to decay at the low end, because they can quickly make an unpalatably thick soup of your sonics. In typical pop, rock and electronica work, you can usually afford to high‑pass filter most effect returns well above 100Hz, as well as applying additional LF shelving or peaking cuts in the couple of octaves above that.

One of the most powerful weapons in the fight against muddy mixes is also one of the simplest: high‑pass filtering.

One of the most powerful weapons in the fight against muddy mixes is also one of the simplest: high‑pass filtering.

Example Mixes: Although mix muddiness tends to be associated with a mix tonality that's heavy in the low-mid range, as in contest submissions 09, 54 and 58, say, brighter mixes such as 21, 22 and 36 are by no means immune to the same kind of clarity problem. Compare these to mixes such as 20, 31, 51 and 63, which handle this area of the spectrum much more effectively.

5: Unhelpful Arrangement

The roots of many a mix problem can be traced back to the musical arrangement, and this simple fact renders many of the budget productions I hear effectively unmixable. If your song's verse has more guitar or percussion layers than its chorus, you're likely to face an uphill struggle if you want the chorus to arrive with a bang. Likewise, there's no sense in having different guitar and keyboard sounds competing in the same pitch register if you want to keep any separation between them in the mix. And unless you create some sense of build‑up in the arrangement itself, it's unlikely that you'll hold the listener's attention all the way to your final chorus. Here are some quick ways to make improvements:

- Try to avoid simply replicating the same arrangement for any similar sections of your track. Dropping a couple of parts from the first verse, for example, can help make the second verse feel a lot fresher and more engaging when it arrives.

- If you're having trouble disentangling parts in your mix, try altering MIDI parts to different chord inversions or pitch‑shifting audio parts to different octave registers, to give each a bit of clear space in the frequency spectrum. Alternatively, put one part's notes in the time‑gaps left between the another part's notes.

Rich reverb decays can quickly swamp your mix, especially in modern upfront chart styles, so try shortening the effect's decay time if your mix is beginning to feel undesirably murky.

Rich reverb decays can quickly swamp your mix, especially in modern upfront chart styles, so try shortening the effect's decay time if your mix is beginning to feel undesirably murky. - Sometimes adding surreptitious overdubs or samples at the mixdown stage (or even editing out whole sections of the song!) is the best way to remedy an arrangement problem, so don't rule out this kind of tactic at the mixdown stage.

Example Mixes

Although a lot of people did stick within the parameters of the multitracks provided, there were many instances where contestants applied creative rearrangement techniques to tackle the mixing challenges presented by the supplied multitracks. Some mixers (most notably 03, 22, 27, 39 and 42) wielded the razor blade to increase the overall pace of development and to bring in the vocals earlier. Mixes 18 and 52 wheel out a variety of more extrovert mix effects as ear candy, while mixes 03, 18, 56, 59 and 61 make use of additional synth/sample textures to fill out the chorus texture or add extra atmosphere during the verses. Vocals were frequently flown around to other parts of the mix and treated with pitch‑shifting to generate synthetic harmony parts, as you can hear in mixes 05, 26 and 40, for instance, plus there are some interesting larger‑scale arrangement 'drops' showcased in mixes 27, 28 and 56. The most successful combination of all these different approaches for me, though, can be heard in mix 20 — a version that only just missed winning the contest outright.

6: The Wrong Reverb

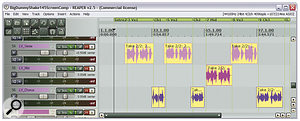

If the layout of audio in your DAW's main window looks anything like this, with lots of simple repetition of arrangement textures, then you'll almost certainly struggle to build up a sense of tension or momentum in the mix.

If the layout of audio in your DAW's main window looks anything like this, with lots of simple repetition of arrangement textures, then you'll almost certainly struggle to build up a sense of tension or momentum in the mix.

Reverb can do so many things in a mix: gelling sounds, changing timbres, simulating an acoustic environment, lengthening note decay. As such, one of the important tricks to using reverb successfully at mixdown is to concentrate on preventing it from doing things you don't actually want! Most home‑grown mixes have difficulties with this to some extent, with the result that too much or too little reverb is typically applied. After all, it stands to reason that if you try to blend a sound into the mix with a reverb that's not good at blending things, say, then either you're going to stop short of the amount of blending you need, or you're going to turn the effect up to a point where its sound becomes overbearing in other ways. The following tips provide a useful guide to getting your reverbs right:

To give you a little more perspective on your effects settings during the final stages of a mix, try muting each effect return for a few seconds before returning it to the balance. Once your ear has got used to the mix without the effect, it's a lot easier to judge whether it's actually optimised for its purpose.Natural‑sounding reverbs will tend to be better for blending sounds together and giving them a sense of space. Unnatural‑sounding reverbs (such as plates, springs and quirky algorithmic digital devices), on the other hand, will tend to offer more scope for creative enhancement of instrument timbres.Bright effects usually sound more obvious at a lower level, so be prepared to roll off the high frequencies of effect returns if you want your reverbs to keep a lower profile.The length and level settings of a reverb are interdependent. If you misjudge one of them, you'll struggle to find a satisfactory setting for the other.When you're close to completing your mix, bypass each return for a few seconds during playback. This can really help you to gauge whether each effect is set up right, especially in terms of overall tone, level and decay time.If you're looking for a more up-front sound, using heavier compression or adding in things like synth pads can both reduce the need for reverbs in a mix. Tempo‑sync'ed delay effects can also provide a more transparent substitute for reverb in a lot of cases.

To give you a little more perspective on your effects settings during the final stages of a mix, try muting each effect return for a few seconds before returning it to the balance. Once your ear has got used to the mix without the effect, it's a lot easier to judge whether it's actually optimised for its purpose.Natural‑sounding reverbs will tend to be better for blending sounds together and giving them a sense of space. Unnatural‑sounding reverbs (such as plates, springs and quirky algorithmic digital devices), on the other hand, will tend to offer more scope for creative enhancement of instrument timbres.Bright effects usually sound more obvious at a lower level, so be prepared to roll off the high frequencies of effect returns if you want your reverbs to keep a lower profile.The length and level settings of a reverb are interdependent. If you misjudge one of them, you'll struggle to find a satisfactory setting for the other.When you're close to completing your mix, bypass each return for a few seconds during playback. This can really help you to gauge whether each effect is set up right, especially in terms of overall tone, level and decay time.If you're looking for a more up-front sound, using heavier compression or adding in things like synth pads can both reduce the need for reverbs in a mix. Tempo‑sync'ed delay effects can also provide a more transparent substitute for reverb in a lot of cases. If your EQ settings look anything like the ones from this Mix Rescue submission, your mix is very likely to suffer from the same harshness problems, because of the repeated emphasis on the 2‑5kHz region using comparatively CPU‑light processing.

If your EQ settings look anything like the ones from this Mix Rescue submission, your mix is very likely to suffer from the same harshness problems, because of the repeated emphasis on the 2‑5kHz region using comparatively CPU‑light processing.

Example Mixes: Mixes 17, 23 and 27 all have long reverb treatments that are rather too prominent in the balance, presumably in an attempt to gel the instruments and vocals together — a task that's usually more successful carried out with shorter, ambience‑style patches. (The reverb tails are also quite bright in these three mixes, which only reinforces the sense that the effects are being artificially generated.) Mix 16, on the other hand, has the opposite problem, in that it's using too much short reverb to try to enhance instrument sustain and to create the illusion of a larger space. Here, a few longer delays or reverbs would have been more effective, allowing the blending treatment to assume a more natural‑sounding background role. Mixes 06, 10 and 23 also use too much reverb for me, and I think that stronger use of compression would have been a better alternative, not least in fattening the drums and keeping the mix as a whole clearer and more upfront.

7: Harshness

Every home studio should have at least one dedicated transient processor, if only because they can deal with overly spiky acoustic recordings so transparently. There are now plenty of plug‑in options to choose from, including SPL Transient Designer, Stillwell Audio Transient Monster, and Voxengo TransGainer shown here.

Every home studio should have at least one dedicated transient processor, if only because they can deal with overly spiky acoustic recordings so transparently. There are now plenty of plug‑in options to choose from, including SPL Transient Designer, Stillwell Audio Transient Monster, and Voxengo TransGainer shown here.

Any part of your mix that's rich in the 2‑5kHz frequencies will normally sound closer to the listener, not least because the human hearing system is most sensitive to information in that region. Little surprise, then, that so many home recordists pile masses of 2‑5kHz on everything — vocals, guitars, drums, cymbals — with the result that the mix as a whole ends up sounding harsh. However, it's not just frequency response that can make a mix feel abrasive, because untamed high‑frequency transients can be another crucial factor too. Here are some easy ways to avoid harshness in your mix:

- Try to avoid boosting in the 2‑5kHz region, especially with CPU‑light digital equalisers, which can occasionally sound a bit crunchy up top. If a given instrument isn't coming through well in that spectral area, apply some cuts to competing channels instead.

- Avoid EQ'ing in solo, because most people instinctively try to give every track a 'forward' sound if they work like that. It's what your tracks sound like in the context of the mix that really counts.

- If you want to move synth or electric‑guitar rhythm parts out of the harshness zone, try using pitch‑shifting or distortion to move some frequencies into a different part of the audio spectrum.

- Be careful with the Attack Time control if you're compressing percussive material heavily, because slower settings can allow high‑level transients through the processing before the gain reduction has the chance to take hold.

- To tone down overly spiky piano or acoustic‑guitar tracks, experiment with some of the dedicated transient processors now available, such as SPL's Transient Designer, Stillwell Audio's Transient Monster, Sonnox Transient Modulator and Voxengo's Transgainer. Because these don't rely on a threshold system to work, they tend to deal with the problem more 'musically' than traditional dynamics units.

Example Mixes: Given that the competition multitrack combined thrashy drums and heavily overdriven electric guitars, it's little surprise that many of the submitted mixes suffer from harshness problems. Take mixes such as 13, 27 and 54, for instance: despite the considerable variance in their overall mix tonalities, they all share the kind of upper mid-range emphasis that quickly becomes a bit grating on the ear, especially when the extra guitar layers hit during the middle section. Overly sharp snare transients are also a bit hard on the ear in mixes such as 24, 34 and 56.

8: Buried Details

Even in cases where the mix tone is free of muddiness and send effects have been applied appropriately, musicians who mix at home rarely present their material in the best light, simply because they don't actively direct the listener towards the music's most appealing aspects from moment to moment. Yes, the bass part might be dull as ditchwater most of the time, but that doesn't mean you can't push up the fader for its one little fill if there's nothing else more thrilling happening at that time. Any and all parts can benefit from micro‑level fader rides like this, but few tracks more so than lead vocals, where riding up the details can mean the difference between the listener understanding the lyrics and not. Here are some useful tricks to focus on all those lovely little details:

- Whether the main part in your mix is a lead vocal, instrumental solo, or some other hook, it's not unusual for it to have the odd lull — a comparatively featureless sustained note, say, or a gap between phrases. Whenever you hear one of these, have a quick hunt amongst the rest of the backing tracks to see if there's anything else that might briefly poke out of the texture to provide some welcome diversion.

- Turning down a couple of backing parts underneath a lead vocal line can help reveal more of the singer's subtle vocal inflections without recourse to nuclear‑grade vocal compression.

- It's standard practice on a professional level to carefully automate lead vocals in order to maximise the intelligibility of the lyrics, so don't forget to give that process the time it needs. While you're at it, try fading up the ends of some of the note tails — you'd be surprised how often they contain characterful little bits of hidden phrasing that can really make a performance seem more emotional.

Here you can see a section of the Mix Rescue remix project from August 2009. Notice how the piano (blue) backing level is being faded up between the vocal phrases (red) to help direct the listener's ear in that direction whenever the vocal interest wanes.

Here you can see a section of the Mix Rescue remix project from August 2009. Notice how the piano (blue) backing level is being faded up between the vocal phrases (red) to help direct the listener's ear in that direction whenever the vocal interest wanes.

Example Mixes: When someone's using detailed automation carefully, it's usually tricky to hear what's going on in absolute terms — in other words, you shouldn't get an active sense of faders being waggled about if the engineer knows what they're doing! What you should get, though, is a sense of the music being easier to follow and more engaging from moment to moment, something which is most apparent in mixes 20, 31 and 63, all of which made my own shortlist. However, to be honest, none of the competition entries really shone in this area, which only serves to highlight how commonly the importance of micro‑level automation is underestimated.

9: Weak Payoffs

These two screens show the level of detail that goes into vocal automation on today's commercial chart productions. The lower, right-hand screen is from Fraser T Smith's mix of Tynchy Stryder's 'Number One', and the upper one from Greg Kurstin's mix of Lily Allen's 'The Fear'. That's what you're up against!

These two screens show the level of detail that goes into vocal automation on today's commercial chart productions. The lower, right-hand screen is from Fraser T Smith's mix of Tynchy Stryder's 'Number One', and the upper one from Greg Kurstin's mix of Lily Allen's 'The Fear'. That's what you're up against!

Any important instrumental or vocal part in your mix may well require different mix treatment to cater for the balance demands of different sections of the musical arrangement. If so, then 'multing' the recording, by editing sections of it to separate tracks in your DAW (as shown here), is a simple way to manage the practicalities.

Any important instrumental or vocal part in your mix may well require different mix treatment to cater for the balance demands of different sections of the musical arrangement. If so, then 'multing' the recording, by editing sections of it to separate tracks in your DAW (as shown here), is a simple way to manage the practicalities.

Anyone who's ever mixed a song will at some time have come up against the problem that their choruses sound underwhelming compared with their verses — or, to put it in more general terms, that some section of the arrangement isn't delivering the required emotional payoff. There can be lots of reasons for this kind of 'long‑term dynamics' problem, but the most fundamental one is failing to pace the mix's build‑up correctly, such that the sonics peak too early. In this situation, the temptation is always to try to push the subjective 'size' of a mix's climaxes beyond the point where they sound their best, thereby introducing all sorts of potentially unmusical processing and distortion side‑effects. Here are some ideas to help you achieve the impact you want from a tune:

- If you feel that a section of your song is still failing to deliver the goods, even after you've taken its sonics as far as you reasonably can, why not try working backwards? See if you can make the previous section smaller‑sounding, in some way, than it currently is.

- Remember that different songs, and different mix sections within a song, may demand different sounds from the same instrument. A ballad's solo piano introduction, for example, will probably require a much fuller sound than the piano vamping tucked into a full‑band rock rhythm workout. Splitting your recordings across different tracks with audio editing (sometimes referred to as multing) is a simple way of implementing this idea, as you don't need to automate all the processing, simply exercise the mutes!

Although applying low midrange boost to a lead vocal, as in this screenshot, can give it a warm and intimate character, the danger is that it can also make the rest of the backing track sound small, so any such boost needs to be handled with care.

Although applying low midrange boost to a lead vocal, as in this screenshot, can give it a warm and intimate character, the danger is that it can also make the rest of the backing track sound small, so any such boost needs to be handled with care. - Both the level and the timbre of your lead vocals will be critical to the perceived power of the backing arrangement. In particular, if you fade the vocal too high up in the balance, or give it too much lower mid-range, the chances are that it will start to make the rest of the production sound small.

Example Mixes: Managing the long‑term dynamics of this particular mix was probably the greatest challenge presented by the competition multitracks, the crux of the matter being that the middle section, with its strident additional guitar overdubs, tended to make the onset of the subsequent final chorus feel like something of a letdown — as in mixes 21 and 64, for instance. Increasing the chorus vocal levels is the tactic taken by mixes 17 and 28, but this isn't actually that successful, as it makes the band sound rather small by comparison with the singer. Mixes 22 and 33 thicken the chorus texture using additional distortion and widening effects respectively, but fall slightly foul of harshness and mono incompatibility into the bargain. More successful, to my ears, are mixes such as 38 and 46, which seemed to deliberately restrain the middle‑section's guitars (so that the chorus can still trump them in some way) or those which surreptitiously inflate the final chorus with extra textural layers — mixes 03, 07, or 20, for instance. There is also some excellent lateral‑thinking from mixes 20 (in its second version), 27, and 58, all of which use edited‑together arrangement drops as a means of partially side‑stepping the whole issue.

10: Inappropriate Processing On The Mix Bus

It's tempting to try to improve your sound by applying mastering‑style processes, such as multi-band dynamics or loudness maximisation, to your output bus during mixdown, but it's seldom a good idea in practice! This kind of processing usually confuses most mix decisions completely, and you end up chasing your tail — so while they're useful tools, it's better to leave them alone until you've finished the mix!

It's tempting to try to improve your sound by applying mastering‑style processes, such as multi-band dynamics or loudness maximisation, to your output bus during mixdown, but it's seldom a good idea in practice! This kind of processing usually confuses most mix decisions completely, and you end up chasing your tail — so while they're useful tools, it's better to leave them alone until you've finished the mix!

This one is a bit of a tightrope, because there are two different ways you can come a cropper. On the one hand, it can be impossible to achieve the necessary degree of mix 'glue' and/or aggression in certain modern styles without a generous helping of dynamics processing over your master channel; but on the other hand, you can get into all sorts of difficulties if you effectively try to master your production while you're still mixing it. Follow this advice and you should get better results:

- Try to get the overall balance of your track working before you start applying mix‑bus compression. Although you may subsequently need to adjust some faders in response to the bus dynamics, in my experience it's easier to do this than to have the compressor's gain‑reduction action interfering with all your initial balancing decisions.

- Steer clear of using multi-band dynamics processors or dedicated 'loudness maximisers' over your main outputs during mixdown. Although these can be useful as part of a separate mastering stage, they do make it very difficult to judge what's going on when judging level balances, channel processing, and effects settings.

- If you're deliberately driving a full‑band compressor hard to generate obvious gain‑pumping effects, consider using a processor with a wet/dry mix control so that you have the option to reduce any transient‑smoothing side‑effects of such heavy treatment.

Where you're using buss compression to achieve more aggressive effects, then try one which has a built‑in parallel processing option or wet/dry mix control — it'll often let you get more obvious gain pumping with fewer negative side‑effects as far as the fidelity of powerful kick/snare mix transients is concerned.

Where you're using buss compression to achieve more aggressive effects, then try one which has a built‑in parallel processing option or wet/dry mix control — it'll often let you get more obvious gain pumping with fewer negative side‑effects as far as the fidelity of powerful kick/snare mix transients is concerned.

- If you're in any way uncertain about the validity of the master‑bus processing you've applied, do make sure you bounce down a version of your final mix without it, to hedge your bets.

Example Mixes: Many of the competition mixes didn't seem to use enough bus compression to suit the aggressive musical style — mixes 05 and 30, for instance, or even the overall contest winner, mix 63. In the circumstances, something more along the lines of mix 31 or 33 feels about right to me. There were also inevitably people who drove their master processing considerably harder, though, such as in mixes 26 and 52, both of which feel rather overbearing as far as level pumping is concerned, while introducing undesirable transient side‑effects and distortion products. Mixes 50 and 58 are also over-compressed, for me, because their fast‑attack processing irons out much of the short‑term dynamics excitement and dulls the transient definition. Mix 42 is pretty much ruined by its heavy‑handed multi‑band dynamics, which is a shame, as it turns out that the unprocessed version subsequently submitted has a lot to recommend it.

One Song, 100 Mixes!

The competition mixes I've used as audio illustrations in this article were carried out in March and April this year for a contest at www.Mixoff.org, a site that's home to a family of mixing collaboration forums. The song 'Blood To Bone', by a talented alt‑rock band called Young Griffo, was provided in raw multitrack form for anyone on the forum to download, and I agreed to provide a detailed critique of any mix submitted within the first couple of weeks. In the end, more than 100 mixes were supplied, of which I critiqued around 60, and I've since consolidated them all to a dedicated web page, so that it's easy to listen to any of them and read the critiques alongside. You can even still download the raw multitracks if you fancy having a crack at them yourself!

The competition mixes I've used as audio illustrations in this article were carried out in March and April this year for a contest at www.Mixoff.org, a site that's home to a family of mixing collaboration forums. The song 'Blood To Bone', by a talented alt‑rock band called Young Griffo, was provided in raw multitrack form for anyone on the forum to download, and I agreed to provide a detailed critique of any mix submitted within the first couple of weeks. In the end, more than 100 mixes were supplied, of which I critiqued around 60, and I've since consolidated them all to a dedicated web page, so that it's easy to listen to any of them and read the critiques alongside. You can even still download the raw multitracks if you fancy having a crack at them yourself!

Monitoring

A specialised single‑driver mixing speaker, such as Pyramid's Triple‑P shown here, is one of the best equipment investments you can make if you're mixing at home or in a small college studio.

A specialised single‑driver mixing speaker, such as Pyramid's Triple‑P shown here, is one of the best equipment investments you can make if you're mixing at home or in a small college studio. One of the most powerful mixing tools available may already be sitting on your shelf!Monitoring is a big issue when it comes to mixing, which is fair enough — you can only really mix what you can hear. That said, it's perfectly possible to create decent‑quality mixes on comparatively modest equipment if you play your cards right. First of all, whatever you plan to spend on monitor speakers, I think you should try to plough the same amount of money into acoustic treatment to make the investment worthwhile. If you need suggestions for acoustic treatment, check out the web site archive of Studio SOS columns, which offer dozens of real‑world examples of affordable speaker and acoustics setups.

One of the most powerful mixing tools available may already be sitting on your shelf!Monitoring is a big issue when it comes to mixing, which is fair enough — you can only really mix what you can hear. That said, it's perfectly possible to create decent‑quality mixes on comparatively modest equipment if you play your cards right. First of all, whatever you plan to spend on monitor speakers, I think you should try to plough the same amount of money into acoustic treatment to make the investment worthwhile. If you need suggestions for acoustic treatment, check out the web site archive of Studio SOS columns, which offer dozens of real‑world examples of affordable speaker and acoustics setups.

My second suggestion is to get hold of a small, single‑driver mixing speaker (such as Avantone's Mix Cube, pictured, or Pyramid's Triple‑P), and use it to listen to your mix in mono. The additional insight into your mix balance this kind of monitoring provides in home‑studio environments is extraordinary, and well worth the additional outlay, especially if you don't have the budget for proper nearfields and are thus obliged to carry out your mixing work primarily on headphones.

As far as monitoring technique is concerned, the main thing to remember is to listen at a variety of different monitoring levels, and to take regular breaks to keep your ears as fresh as you can. Switching between different monitoring systems while working can help improve your objectivity too.

Mix Referencing

One of the best mixing aids is probably already sitting on your shelf: your own record collection. About the cheapest way to improve your mixing is to take the time to line up your favourite commercial productions against your own work (matching the loudness if necessary, to enable a reasonable comparison). What amazes me, though, is how few home mixers take the time to do this in anything more than a cursory manner. I dedicated a whole article to this subject back in SOS September 2008 (/sos/sep08/articles/referencecd.htm), but the most important thing to remember is just to take your time selecting suitable reference tracks, so that you set yourself the most challenging goal. Although the reality of continually struggling to reach such a high benchmark may feel a bit depressing at times, there's nothing to beat it when it comes to ensuring that you always achieve a solid quality level.

Further Reading

There's only so much I can cram into an article like this, so on the SOS web site I've placed a list of useful SOS articles that go into much more detail about how to tackle the 10 'mistakes' described here. This includes a number of Mix Rescue features, complete with audio examples.