This month, we breathe life into a track by restructuring it to avoid unnecessary repetition, adding subtle new parts, employing various mix tricks and finally applying a little DIY 'mastering' polish...

Here you can compare Dave's original arrangement in Cubase 4 (right) with Mike's remix arrangement in Reaper 3 (below). Notice the multing of the drums, vocals and guitars in the remix, as well as the new arrangement layers (all the green tracks).

Here you can compare Dave's original arrangement in Cubase 4 (right) with Mike's remix arrangement in Reaper 3 (below). Notice the multing of the drums, vocals and guitars in the remix, as well as the new arrangement layers (all the green tracks).

This month's mix comes from SOS reader Dave Gerard, who requested some advice on how to improve the overall production of his song 'Never Stop'. The strength of the anthemic chorus was clearly apparent on first listen, but both the arrangement and the sonics felt very much at the demo stage. In particular, the backing track felt rather too repetitive, and despite the heavy reverb in evidence, there was a sense that the arrangement needed filling out. These issues both needed careful attention to bring about a more successful remix, so I'll focus on each in turn.

Restructuring & New Fills

Too much repetition was one of the biggest issues with this track, leaving scarcely any light and shade in the arrangement and starving the mix of musical momentum. Clearly, a slow‑burn number like this doesn't demand fresh ear‑candy every second, but you've still got to be careful to avoid dead weight, especially if you're relying on programmed sound sources (such as the drums here) which, by their nature, will tend to lack humanity.

The main structural offenders were the bridge sections, which just seemed to be treading water, so I halved those in length fairly early on. It also felt a bit strange to me having a bridge section between the first chorus and the subsequent verse, because it somehow squandered the momentum of the chorus. A better use for that section seemed to be putting it just before the second chorus instead, allowing some expansion of the texture into the chorus and simultaneously defeating the expectation thus far that chorus would directly follow verse.

Repetition was also a more short‑term feature of most of the parts, so I did a small amount of work to try to introduce fills here and there, although opportunities were fairly thin on the ground — pretty much just a few pitch‑shifted/time‑stretched bass notes preceding section changes, and a little shuffling around of drum hits.

Mutes & Mults

Mike used several methods to give more of a drum‑machine sound to the verse/bridge drums, amongst them frequency‑restricting the kick and snare tracks with EQ and bussing the whole kit through SSL's lo‑fi Listen Mic Compressor.

Mike used several methods to give more of a drum‑machine sound to the verse/bridge drums, amongst them frequency‑restricting the kick and snare tracks with EQ and bussing the whole kit through SSL's lo‑fi Listen Mic Compressor.

The bulk of my efforts were focused on increasing textural variety, as a means of differentiating the song sections and providing some sense of dynamics through the song. A certain proportion of this simply involved judicious pruning of what was already there: for example, progressively paring down the drum parts before the first chorus; excising the synth, high guitar and backing vocal parts from the first chorus; and saving up some of the bridge guitar parts as features for later in the song. Again, though, there was a limit to how much I could do, because there wasn't a tremendous amount of raw material to work with.

I was able to get more variety from some of the available parts by giving them different sounds for different sections of the track. I did this using multing, in other words by hiving off different sections of a given part to different tracks for independent processing. The most clear‑cut example of this process in the remix is the drums, which occupy two separate sets of tracks: one for the verses and bridges, and one for the chorus sections. I noticed that the programmed drums sounded less artificial during the choruses than during the verses, so I decided to make this artificiality appear intentional by transforming them into more of a beatbox sound outside the choruses.

The two main ways I achieved this were by truncating the kick and snare tails using a gate plug‑in, and then bussing the whole verse/bridge drums mix through SSL's super‑crunchy Listen Mic Compressor plug‑in. However, EQ further differentiated the sections too. The kick, for instance, started with a medium‑resonance, high‑pass filter at 66Hz, compacting the sub‑bass frequencies and adding 2‑3dB of gain at around 100Hz, and a gentle low‑pass filter rolling off the presence above 2kHz. This restrained sound contrasted with a more open chorus EQ setting comprising 20Hz high‑pass and 8kHz low‑pass filtering.

With the snare, I took a similar approach, bracketing it into the 250Hz‑8kHz region with filters during the verse/bridge and then replacing the filters with 2dB peaking‑filter cuts at 220Hz and 4kHz for the chorus. The chorus snare felt like it needed to be a bit fatter too, so I rounded its peaks somewhat using the soft‑clipping options in GVST's GClip. Different send levels to some of the mix effects were also part of the equation here, giving the chorus a wider and more ambient presentation.

Multing also helped out with the main rhythm guitar part, which I kept compact, central and quite warm‑sounding for the verse and bridge, before switching to a harder, clearer, double‑tracked sound for the choruses. The verse and bridge EQ was fairly minimal during the verses (a 3dB boost at 3.4kHz from a fairly wide peaking filter in T‑Rack's Classic Equaliser plug‑in), whereas the chorus guitar was leaner and brighter, courtesy of additional 170Hz high‑pass filtering, ‑3.5dB of low shelving, a 4dB peak at 1.1kHz, and 6dB of 3kHz shelving boost. Even with the different EQ, though, this guitar still felt like it wasn't clear enough in the final mix, so I also plumbed it through Stillwell Audio's Bad Buss Mojo distortion plug‑in, to make it a bit less clean‑shaven! Whenever I come back to this plug‑in, I'm always a bit mystified as to which control does what, but it does nonetheless offer a tremendous range of different distortion flavours, and (unlike many other distortion plug‑ins) it also has a wet/dry mix control, which makes it suitable even for subtler mixing applications.

The lead vocal track was another that used completely different processing chains and effects settings for the verses and choruses. The verses used the Universal Audio UAD2 card's SSL channel emulation to provide one layer of compression and a good deal of HF cut between 3kHz and 6kHz, then the Fairchild 670 emulation provided further dynamic control and extra warmth, before a Pultec EQ model restored a little air above 12kHz. The choruses, on the other hand, had only a little EQ (a couple of decibels of boost at 120Hz from 112dB's Redline Equaliser plug‑in) and leaner‑sounding dynamics from the UAD2's LA3A emulation and Flux's Pure Limiter II, to leave a sound better able to penetrate the thicker chorus texture. The verse effects were softer and more diffuse too, majoring more on stereo widener, ambience and plate reverbs, where the choruses relied more heavily on simple tempo‑sync'ed delay, an effect that takes up less space in the mix, allowing more scope for the other instrumentation.

Guitar Support

Here you can see the arrangement of the added cymbals during the final chorus section. At the top are a couple of ride cymbals, then a pair of mallet‑roll cymbal samples, and finally a selection of crash cymbals.

Here you can see the arrangement of the added cymbals during the final chorus section. At the top are a couple of ride cymbals, then a pair of mallet‑roll cymbal samples, and finally a selection of crash cymbals.

Despite the edits and mults, it quickly became apparent to me that there was only so much mileage to be had from the original tracks, and that I'd have to add some new ingredients to reach a more satisfying conclusion. The chorus sections were a case in point, because there just weren't enough layers to create the kind of lush sound that Dave's soaring vocal lines seemed to demand. It wasn't that I thought we needed extra musical parts here, it's just that the general production sonics felt rather anaemic.

One of the oldest tricks in the book for filling out a guitar arrangement is simply to layer some double‑tracked open‑fifth chords in the background. Such parts aren't usually designed to be heard in their own right (they're pretty boring), but they can make all the other guitar parts sound like they've had a good solid bacon butty! In the past I've overdubbed the chords myself for parts like this when I've not had a tame guitarist to hand, but I recently reviewed an excellent Nine Volt Audio sample library called Pop Rock Guitars which provides a much quicker solution, and saves an unsuspecting public from the horrors of my pathetic guitar technique into the bargain!

Although Pop Rock Guitars has a lot of nice musical rhythm‑guitar riffs and melodies, what I used for this remix were the simple eighth‑note REX loops, which are provided for every different scale note. If your sequencer supports REX import, the loops will automatically match themselves to your song's tempo, and you can then choose whichever pitches work with your chord progression. The loops are played by two different guitars as well, so it's a snap to pan the parts for a wide double‑tracked sound, which is what I did in this situation. One further single‑note line from one of the library's construction kits spiced things up a little further, pulling out more of the song's root note in the middle registers and also providing an additional layer during the final bridge/solo section.

Synth Padding

Mikko Hyyrylainen's freeware Satyr 8 synth was put though Schwa's Oligarc Phaser to enrich and widen the upper end of the guitar texture during the choruses.

Mikko Hyyrylainen's freeware Satyr 8 synth was put though Schwa's Oligarc Phaser to enrich and widen the upper end of the guitar texture during the choruses.

While I followed Dave's lead to an extent by warming up the chorus guitars with some reverb and tempo‑sync'ed delay, the levels weren't nearly as high as Dave's and the balance was more in favour of the delays than the reverbs, because this helps to keep the sound more up-front. Instead of using reverb to add richness, I therefore turned to another old favourite of mine: a synth pad. Dave had already included a synth part that partly fulfilled this purpose, but it was only a single‑note line that didn't really do the job, so I ended up putting in an additional one myself.

Normally, pads tend to be quite dull‑sounding to add warmth, but in this case I wanted to give extra brightness to the guitar chords without over-emphasising their high‑frequency distortion components, so I used a fizzy dual‑sawtooth patch from one of my favourite freeware synths: Mikko Hyyrylainen's virtual analogue Satyr 8. I started by programming a moderately dense low‑register part with four voices, and then gently rolled off its output below about 1kHz with a high‑pass filter to remove most of the lower harmonics. Once this was done, I tried to fade it into the mix just until the point where it began enhancing the apparent high end of the guitars, but I found that the 4kHz area of the synth spectrum poked out too obtrusively within the context of the mix, so I had to cut about 4dB from that with a peaking filter before I achieved the desired balance of high‑end enhancement and apparent inaudibility. A touch of Schwa's Oligarc Phaser gave me a little additional stereo width too — I'm a sucker for phaser on synths!

Added Cymbals & Hi‑hats

A combination of two background noise sources (the Vintage and VST Editions of Retrosampling's Audio Impurities) was used to give extra cohesion to the mix, so that less reverb was required.

A combination of two background noise sources (the Vintage and VST Editions of Retrosampling's Audio Impurities) was used to give extra cohesion to the mix, so that less reverb was required.

One of the things that was really letting down Dave's drum sound, to my ears, was the cymbals, which were mono and had a thin timbre. That meant that although he'd tried some cymbal accents to highlight the chorus entries, they were falling rather flat. For the remix, I decided to create new chorus parts using the general‑purpose cymbals from Spectrasonics' old Back Beat sample library (now available as a SAGE Expander for Stylus RMX): a simple low‑level repeating ride‑cymbal part, alternating between two samples, provided a bit of width and air to the texture, while accents were provided by four other cymbal crashes in various combinations.

To keep the crash cymbals tucked into the background, I shelved off a few decibels above 5kHz (slightly different amounts for each sample) and pretty much removed any stick noise by turning the Attack parameter in Reaper's Jesusonic Transient Controller plug‑in down to minimum. Further compression and some delay send from these parts extended the cymbal tails, and then, as a final touch, I added in some cymbal mallet rolls (another old chestnut!) from Soundlabel's Xtreme Whooshes sample library, to give some subliminal impetus into the section boundaries.

Those additions made a big impact on the chorus, so I now turned my attention to the verses, which also suffered from lacklustre upper percussion, this time the hi‑hat. Not only did it have similar sonic problems to Dave's chorus cymbals, but it also followed a rather halting part which seemed to drag. Once again, I rifled through my sample library and this time pulled out Mads Michelson's old Groovemasters Drums WAV library, which includes a selection of hi‑hat‑only loops. A much more solid part was soon constructed, and by shuffling around half a dozen loop variations I was also able to introduce another couple of subtle fills.

Spit & Polish

The final major arrangement update was an additional electric piano I programmed using the tiny little freeware MDA Epiano plug‑in I usually reserve for musical sketching purposes. The main purpose of this was to add some subtle ripplings around the guitar and bass rhythms during verse/bridge sections, where the production as a whole felt as though it needed an extra dose of warmth and movement. To this end, I bracketed the sound between 145Hz and 9kHz with filters and dipped out 4dB at 4kHz to keep the sound fairly shy and retiring, then I laid on delay, ambience and plate reverb to wash the instrument into the mix. While I was programming the part, I took the opportunity to add another couple of fills, and also found that the sound worked quite well for a simpler oscillating open‑fifths part underpinning the choruses, so that's in there too — although I think you'd be hard pushed to notice it in its own right.

The remaining arrangement tweaks were fairly minor: a couple of cross‑rhythm vocal delay spins to break up the four‑square repetitions of the first two bridges; one of the solo guitar riffs pasted into the final choruses; and an additional solo guitar part provided by Dave when I suggested to him that the second half of the final bridge section might benefit from a couple of melodic features. On top of those, some background noise layers from Retrosampling's two Audio Impurities plug‑ins assisted in binding the mix together with less reverb, while three little subliminal rhythmic loops from Sonic Couture's excellent Abstrakt Breaks sample collections gave the verse/bridge drums some background detail.

As you can see, I added a lot of things to this mix, but I do want to stress that although the combined effect is quite dramatic in the remix, each individual change was actually pretty subtle. As with mix processing, big improvements to the sound are most often achieved by a combination of small tweaks, rather than by bold, broad‑brush changes. It's also worth mentioning that although I've presented my changes in a linear manner, for the sake of writing about them clearly, real‑world arrangement tweaking is actually very much a 'suck it and see' activity, and I was constantly experimenting with different combinations of parts throughout the mix process, muting and unmuting elements to see what helped and what didn't.

But What About The Mix?

The recording room's acoustics had imposed some nasty mid-range resonances on the lead vocal part, so the vocal wouldn't blend properly with the backing until Mike had addressed these with a set of narrow peaking filters.

The recording room's acoustics had imposed some nasty mid-range resonances on the lead vocal part, so the vocal wouldn't blend properly with the backing until Mike had addressed these with a set of narrow peaking filters.

You'd be forgiven for wondering when I'll start talking about any mixing, given the name of the column, but compared with the arrangement work, the mixing itself was mostly fairly straightforward, and in many respects quite similar to that of Turn Back To Spring's 'Another Day Calling' in SOS May 2010. Two parts presented a few extra difficulties, however: the bass and the lead vocal. The bass was probably the most dull‑toned DI part I've ever encountered — so woolly, in fact, that I can only assume it had been inadvertently processed during recording. I just couldn't do anything useful with it, so I threw in the towel and asked Dave to retrack it for me. The new version seemed quite a bit clearer, although I still added in a bit of overdrive to improve the audibility of the line on small speakers. The distortion was an instance of IK Multimedia's Amplitube X‑Gear running in parallel, a setup I generally prefer because you can EQ the return to isolate just the bits you want — in this case, 112dB's Redline Equaliser allowed me to restrict the distortion to a 200Hz‑2kHz region that seemed most effective.

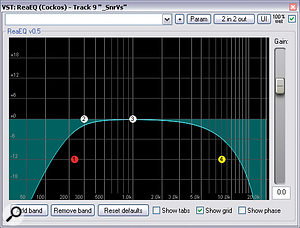

The vocal had a much thornier problem, because it had been recorded in a small, untreated room, which had introduced a series of nasty‑sounding mid‑range resonances. Until these were sorted out, the vocal always seemed to be unpleasantly telephone‑like, no matter what I did with the overall tone, and no dynamics or send effects appeared able to blend the vocal adequately with the mix. After dickering fruitlessly with different equalisers and compressors for a while, it dawned on me that they weren't fixing the underlying problem, whereupon I fired up Schwa's high‑resolution Schope audio analyser and set off on a hunter‑killer mission. Armed with a bank of narrow peaking filters from Reaper's ReaEQ, I slowly tracked down the main culprits by watching for peaks whenever the sound became abrasive, finally settling on 8dB incisions at 350Hz, 416Hz, 700Hz, and 1400Hz, which together seemed to bring the vocal more within the bounds of workability.

Of course, in future Dave should reconsider his vocal recording location and technique, to try to head off this kind of problem at source, as that would make the vocal mixing much easier. Even the quick bodge of hanging up a couple of duvets behind the singing position would probably have made a significant difference here, and if that doesn't do the trick, he should consider recording vocals in some other room, because the recorded results should more than compensate for any extra hassle involved.

Fix Before The Mix

In my experience, the tracks submitted by many Mix Rescue candidates suffer as much from arrangement problems as mixing problems. This month's remix showcases a number of the most common quick fixes for this malaise, so if you're tearing your hair out trying to get a full sound with mix processing alone, you might want to give a few of these alternative tactics a spin for yourself.

Precision Multi‑band Processing

Although I wouldn't class myself as a mastering engineer, I do usually do some mastering‑style processing to the auditioning mixes I send out, so that people can compare my work on a fairly even footing with their own commercial reference tracks. This processing is usually just a question of increasing the loudness to an appropriate level, but in this case I decided to try to make a bit more of the mix's internal details with some fine processing from Flux's Alchemist multi‑band dynamics plug‑in.  Flux's all‑singing, all dancing Alchemist multi‑band dynamics plug‑in helped to improve the detail and smoothness of the final remix file. Here you can see the subtle upward expansion that was applied to the low‑frequency band.This prodigiously complex beast has five frequency bands available and five simultaneous dynamics processors per band, so it's powerful enough to let you do just about anything you want to the dynamics of a signal. However, it's easy to get lost amongst the forest of options and controls, so you have to keep your mind clearly focused on what what you're trying to achieve.

Flux's all‑singing, all dancing Alchemist multi‑band dynamics plug‑in helped to improve the detail and smoothness of the final remix file. Here you can see the subtle upward expansion that was applied to the low‑frequency band.This prodigiously complex beast has five frequency bands available and five simultaneous dynamics processors per band, so it's powerful enough to let you do just about anything you want to the dynamics of a signal. However, it's easy to get lost amongst the forest of options and controls, so you have to keep your mind clearly focused on what what you're trying to achieve.

This mix is a good illustration, because I ended up using three frequency bands of processing which all had quite different settings. The mid-range band, which spanned 135Hz to 2.5kHz, was using a typical mastering‑style, low‑ratio compressor, operating at a low threshold and a ratio of 1.09:1 so that the resulting gain reduction was usually hovering around 1dB. The attack time for this was fairly long (10ms), while the release was short (ranging between 2ms and 22ms in the plug‑in's variable‑release mode), the idea being to bring up little low‑level details between signal peaks but without killing the mid‑range transients.

The make‑up gain for the mid‑range band was set to around 1dB, just to return the overall mix tone to where it was before the compression. With the high band, by contrast, I was keen to add a little more brightness, while at the same time slightly dipping the most prominent high‑frequency transients to keep the sound smooth. For this, then, I chose a slightly higher ratio of 1:2:1, again with a low threshold, and set the attack and release times to their minimum settings. The result was a very skittery gain‑reduction action that closely tracked signal peaks, although it only reached a maximum of 2dB during the loudest moments, and a make‑up gain of only 1dB still increased the subjective brightness, especially during the quieter sections.

While referencing the track against some others in my CD collection, I decided to tone the bass down just a half decibel using the make‑up gain on Alchemist's low band. However, this worked better for the kick drum than for the bass, so I initially tried some more low‑ratio compression to bring out more of the bass line's softer notes. I wasn't happy with this, though, because it seemed to take away some of the attack of the kick drum even after a certain amount of settings massage. So I ditched the idea of normal top‑down compression and went instead for bottom‑up compression (which Flux refer to as de‑expansion). This reduces the dynamic range below the set threshold, rather than above it, which is usually kinder to transients. I used a 1:05:1 ratio and aimed for around a 0.5dB gain change, using reasonably slow attack and release times of 32ms and 48‑100ms respectively.

So overall, although I processed all three bands, I consciously homed in on the particular dynamics adjustment that fitted the bill, rather than just choosing a preset or slapping all five processors onto every band for the hell of it. Multi‑band mastering compression has earned itself a bit of a bad name amongst some engineers in recent years, but it has its uses and shouldn't wreck your mix as long as you take care to use it for clear reasons. Also make sure you compare the processed and unprocessed audio side by side at the same subjective loudness.

Rescued This Month

Dave Gerrard

Dave GerrardSOS reader Dave Gerard wrote, recorded, and mixed the version of 'Never Stop' that features in this month's Mix Rescue remix. Dave performed the lead vocal and all the guitar parts himself, and programmed the drum and synth parts using Toontracks Superior Drummer v2 and NI Absynth respectively. Backing vocals were sung by James Priest, a friend of Dave's who's studying voice at the Trinity College of Music. Dave has some decent kit (including a classic Neumann U87, which he used for the vocals and guitars) but when contacting SOS he mentioned that he thought his recording‑room acoustics might be undermining his recordings, and that he was having difficulty bedding his vocal sounds into his Cubase mix, despite having some nice UAD2‑based plug‑ins on hand. Reverb and panning were also a concern, and overall he felt that he was falling short of the big sounds that he was hearing on records from people like Kings Of Leon and U2 — the parts sounded separate from one another and the song lacked real musical dynamics.

Remix Reactions

"The remix has really blown me away! The change is massive — far beyond what I was expecting was possible. The song sounds glued together in a convincing space and, in particular, the chorus sounds huge and powerful now. The changes Mike's made to the arrangement and production particularly help to add interest to the song, for example cutting unnecessary repeating bits, adding the really nice electric piano part, and using that vocal echo in the instrumental. Although I had some fairly decent equipment, it just goes to show that experience counts for everything! I can't thank Mike and Sound On Sound enough‚ the new version really does sound a million times better!”

Dave has offered to provide SOS readers with all the original audio files for 'Never Stop' if they'd like to try remixing it for themselves — just email him on contact@davegerardmusic.com.

Hear This Mix Rescue For Yourself!

You'll get a whole lot more out of this Mix Rescue if you listen to the before and after mixes and some of the different elements that make up the remix. Go to /sos/jun10/articles/mixrescueaudio.htm, where you can hear the MP3 files or download hi‑res WAV files to audition in your own DAW.