SOS regulars the Travis Waltons, pictured here playing at the Louisiana in their native Bristol, are centred on the talents of songwriter Daniel Flay and drummer Danny Watts.

SOS regulars the Travis Waltons, pictured here playing at the Louisiana in their native Bristol, are centred on the talents of songwriter Daniel Flay and drummer Danny Watts.

Re-focusing a recording: having set out to capture a live-band feel when tracking, our engineer is tasked with steering the mix in a more polished pop direction.

Regular readers will know that I’ve written a few times about my recording and mixing adventures with Bristol-based band the Travis Waltons, and I’ve worked closely with the band’s songwriter Daniel Flay on a number of albums over the last few years. While I do worry a little that they’re in danger of becoming the SOS house band (I prefer to think of us as ‘long-term collaborators’!), I want to return to them here, as there are a few useful points of discussion to draw out of their latest project. This had started out as a reasonably straight-up indie-rock affair, and I described in SOS September 2016 (sosm.ag/sn-0916) how we tracked the drums for the album over a single weekend. The intention was that this album would be much more ‘raw’ than previous offerings, and that it would more closely reflect the band’s live shows.

But ideas evolve, and as the technology we now have at our fingertips allows us to change the course of a project with frightening ease, we ended up experimenting with various approaches to fill out the band’s sound. And, eventually, we found ourselves heading towards a much more lavish, layered and ‘produced’ sound. This month, I want to write about a few of the techniques that I employed to achieve this, and also to reflect on the issues this sort of ‘reinventing’ work throws up for engineers. While it puts us in an increasingly influential position, how do you decide where and when to stop?

All Change!

There was one song on the album, ‘Bright Eyes’, for which the change in direction was particularly dramatic. This has a four-to-the-floor beat, with driving, repetitive guitars and Daniel’s single vocal line. The bass sound came from a combination of a low Minimoog-style synth that had been played in live, and a very mid-heavy bass guitar. Dan was keen for this track to be one of the more ‘accessible’ ones on the album — I may even have heard the word ‘pop’ being used!

The live sound we had already was pretty cool, and everything had been played well, other than for a few ‘characterful’ timing issues. While it had some charm, though, the collective opinion was that this wore off quite quickly as the song progressed, and that the track wouldn’t compare well with the more commercial-sounding productions to which the band now aspired. Now, I do love keeping live performances wherever possible, and I think our ears and our brains connect with them to deliver a sense of excitement. But it’s all about context and, in this instance, things just needed to be tighter and more defined — in other words to head off down a different path.

Marching To A Different Beat

Looking at the drums first, I’d sensibly taken a few steps at the recording stage to ‘future proof’ things. The drummer Danny Watts has a good natural sense of timing, but I still encouraged him to play to what I call a ‘soft’ metronome. This involves the drummer playing to a click but without an accented beat in each bar, which allows the drummer to play ‘around the click’ a little. It’s a compromise of sorts, as the drums won’t necessarily sit slap-bang on the grid in your DAW, but it does help the drummer hold the tempo of the track, and helps you with basic editing between different takes.

The other thing I did was to capture Danny playing some individual drum hits after we’d finished tracking, so that I could take some nice clean samples of his individual drums. I nearly always forget to do this, and don’t often need to use the result, but on this occasion it helped me out a great deal with defining the final drum sound.

At the original drum tracking session, we’d aimed for more of a live feel, but with one eye on a possible change of direction later on from the band, I took a few measures to ensure I’d have some flexibility when it came to mixing.

At the original drum tracking session, we’d aimed for more of a live feel, but with one eye on a possible change of direction later on from the band, I took a few measures to ensure I’d have some flexibility when it came to mixing.

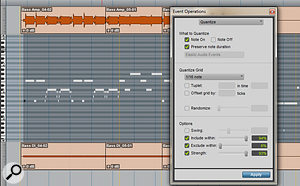

I used Pro Tools’ Beat Detective to quantise the live drums — personally, I still find that this delivers better results than using Elastic Audio or similar audio-warp tools. As the drums weren’t sitting absolutely on the grid, this was quite a time-consuming and challenging exercise for some songs, but the straight 4/4 nature of this particular track meant it was reasonably straightforward to nudge the audio and work to the ‘bars and beats’ grid in Pro Tools.

There are plenty of good tutorials available online if you want to get to know Beat Detective in more depth, but here are a couple of quick pointers for achieving good, natural-sounding results: try to use only the kick and snare to define where the audio is cut, leave drum fills alone where possible, and play with the Strength and Exclude options in the Conform section to find the most natural ‘sweet spot’.

Pro Tools’ Beat Detective tool was used to tighten up the live drums. The Conform controls were set so as to allow a little of the natural timing variation to remain.With the drums tightened up, it was time to see what I could do to fashion a more defined kick- and snare-heavy sound that would suit the track’s new direction, but first I had to attend to the overall balance. As I explained in my article about the drum recording session, Danny’s kit and playing style were very cymbal-heavy. I took a few steps at the recording stage to mitigate this, and I found that switching to the ribbon-mic overheads I’d rigged up set the cymbals back a little in the drum mix.

Pro Tools’ Beat Detective tool was used to tighten up the live drums. The Conform controls were set so as to allow a little of the natural timing variation to remain.With the drums tightened up, it was time to see what I could do to fashion a more defined kick- and snare-heavy sound that would suit the track’s new direction, but first I had to attend to the overall balance. As I explained in my article about the drum recording session, Danny’s kit and playing style were very cymbal-heavy. I took a few steps at the recording stage to mitigate this, and I found that switching to the ribbon-mic overheads I’d rigged up set the cymbals back a little in the drum mix.

Conventional drum gating wasn’t giving me the kick and snare definition I sought, so I experimented with adding some drum samples from my library (comprising both stock samples that come with various bits of software and some that I’ve created myself). This was working fine, but I have an internal ‘taste threshold’ with samples, and dislike drums that sound obviously replaced once they get past a certain level in relation to the real kit. It was at this point that I remembered I’d captured those exposed drum hits, so I set about seeing if samples derived from the actual session might provide the answer.

Roll Your Own Drum Samples

On a very basic level, you can just take one recorded hit of a drum and trigger it with a drum-replacement tool, via MIDI, or even manually (tab-to-transient and paste). Obviously, though, this won’t reflect any of the drummer’s performance — which could be bad, or good, depending on where you’re heading. Dedicated drum-replacement software like Slate Digital Trigger, or Wavemachinelabs Drumagog, on the other hand, allow multiple samples of the same drum hit to be ‘triggered’ according to how hard the original drum was struck. To take advantage of this, you need to record and prepare a number of drum ‘hits’ played at different velocities. Once you begin this process, you’ll start to appreciate just how much work goes into the many commercial sample packages available — I tend to run out of patience with this repetitive editing work very quickly!

When creating your own drum samples, it’s important to ensure you trim as close as possible to the beat’s transient.Rather than prepare dozens of hits for each drum, though, I find that I get enough variation with only around five or six samples, especially when they’re being blended in with an original drum part captured in the same recording session as the samples. I also speed things up by only producing maybe two different balances between the microphones per drum.

When creating your own drum samples, it’s important to ensure you trim as close as possible to the beat’s transient.Rather than prepare dozens of hits for each drum, though, I find that I get enough variation with only around five or six samples, especially when they’re being blended in with an original drum part captured in the same recording session as the samples. I also speed things up by only producing maybe two different balances between the microphones per drum.

Once I’ve finished editing, I’ll typically end up with a folder for each drum with six trimmed stereo samples. A ‘dry’ version, which is primarily the close mics with a touch of overheads, and a ‘room’ option containing a bit of the close-mic signal, but with a more generous balance of the overheads and room mics. I’m also quite happy to do a little EQ and compression before I bounce out the samples, as this gives me a more mix-ready sound.

My method of editing involves bouncing all the snare hits from one balance as a single WAV file, and then carefully trimming each snare hit in a stereo editor like Sound Forge or WaveLab. You need to be precise when preparing the start of each sample, to ensure latency and phase-cancellation doesn’t become problematic, and I like to leave around a second of the drum’s decay after the initial transient.

Slate Digital Instrument Editor was used to create a dynamic drum sample instrument for use in the same company’s Trigger drum-replacement plug-in.Slate Digital Trigger is my plug-in of choice for drum reinforcement at the moment, and Slate provide an Instrument Editor tool for preparing your own TCI files to work with Trigger. This is straightforward to use and involves choosing where to position your samples, depending on their velocity, and then choosing an appropriate articulation algorithm such as ‘snare direct’ or ‘snare room’. You then have your own dynamic, multisample presets to use in your mix.

Slate Digital Instrument Editor was used to create a dynamic drum sample instrument for use in the same company’s Trigger drum-replacement plug-in.Slate Digital Trigger is my plug-in of choice for drum reinforcement at the moment, and Slate provide an Instrument Editor tool for preparing your own TCI files to work with Trigger. This is straightforward to use and involves choosing where to position your samples, depending on their velocity, and then choosing an appropriate articulation algorithm such as ‘snare direct’ or ‘snare room’. You then have your own dynamic, multisample presets to use in your mix.

MIDI From Audio

With the drums tighter and my DIY samples lending the sound a great deal more clarity, I felt I had a solid foundation on which to build a mix... but much like when you begin to paint a room, doing this first bit highlighted the problems elsewhere! Dan was already keen to re-track his guitars, as he’d acquired a new guitar that we’d used on some of the other tracks, and we all preferred that sound, so that wouldn’t be a problem. The bass parts, though, I hoped to salvage, so I set about finding the best way of getting the live synth bass to ‘sit’ better with the quantised drums; I’d then try and balance this with the bass guitar.

Pro Tools’ Elastic Audio was used to tighten key parts of the bass guitar recording — though care was taken not to ‘correct’ the life out of it.I use both Pro Tools and Ableton Live and each has a number of features for adjusting the timing of audio tracks. Using Pro Tools’ Elastic Audio, I gave the mid-range heavy bass guitar a little help, dragging a few key notes manually to tighten things without sacrificing the live feel.

Pro Tools’ Elastic Audio was used to tighten key parts of the bass guitar recording — though care was taken not to ‘correct’ the life out of it.I use both Pro Tools and Ableton Live and each has a number of features for adjusting the timing of audio tracks. Using Pro Tools’ Elastic Audio, I gave the mid-range heavy bass guitar a little help, dragging a few key notes manually to tighten things without sacrificing the live feel.

The synth bass provided the track’s low end, though, and needed to be rock solid against the drums. This was a very simple root-note affair, and a fairly generic sub-bass sound that was almost a simple sine wave. Thus, I figured, it could easily be recreated with a soft synth, so I set about extracting a MIDI part from the audio bass track. A number of DAWs now have the ability now to turn audio into MIDI, but in this instance I used Melodyne. It was a ridiculously easy process that involved loading the bass part into the software, selecting it, and then saving the part as a MIDI file. Once I’d imported that file into Pro Tools, I was able to quantise a new synth-bass part so that was tightly sync’ed to the drums. Then, it was a simple question of finding a nice blend between the synth and bass guitar.

Adventures In Vocoding

MIDI derived from the low synth-bass audio file (via Melodyne) was quantised to sit tightly with the live drums.At this point, we were all buoyed by our success in re-moulding the recordings to fit the band’s new objective, but it was also the point at which a few alarm bells started ringing in my head. It was suggested that I apply similar techniques to the guitars in the track, which I felt would be a step too far, so I suggested we put further timing correction on hold and see how things felt after a while of living with the new sound and feel of the song. The band were happy to trust me on this.

MIDI derived from the low synth-bass audio file (via Melodyne) was quantised to sit tightly with the live drums.At this point, we were all buoyed by our success in re-moulding the recordings to fit the band’s new objective, but it was also the point at which a few alarm bells started ringing in my head. It was suggested that I apply similar techniques to the guitars in the track, which I felt would be a step too far, so I suggested we put further timing correction on hold and see how things felt after a while of living with the new sound and feel of the song. The band were happy to trust me on this.

Their next request was to audition a vocoder effect on the lead vocal in the chorus. I’ve heard this used tastefully on a number of songs recently and after discussing a few references, I understood the kind of thing that Dan had in mind. But, vocoding not being something I’ve done a lot of, I didn’t have a favourite and familiar tool to reach for, and fishing around in my plug-in folder created some pretty crazy sounding — and completely inappropriate — vocal effects!

To create the vocoder effect for the chorus vocal, Melodyne was used to turn the vocal melody into a MIDI file. Instances of the Waves Morphoder plug-in were then used on both the MIDI and remaining audio vocal track to produce the vocoder effect.A quick browse on the Internet threw up a few options to try, though. My first port of call was to activate a trial of the Waves Morphoder plug-in. A quick glance at the manual suggested I could easily do what I was attempting if I could interpret the vocal melody as a MIDI part. As I had already run the chorus vocal part through Melodyne to tighten up a few notes here and there, things quickly fell into place. With a few clicks of the mouse, and using the same technique as on the bass synth, I had a MIDI file that followed the vocal melody perfectly.

To create the vocoder effect for the chorus vocal, Melodyne was used to turn the vocal melody into a MIDI file. Instances of the Waves Morphoder plug-in were then used on both the MIDI and remaining audio vocal track to produce the vocoder effect.A quick browse on the Internet threw up a few options to try, though. My first port of call was to activate a trial of the Waves Morphoder plug-in. A quick glance at the manual suggested I could easily do what I was attempting if I could interpret the vocal melody as a MIDI part. As I had already run the chorus vocal part through Melodyne to tighten up a few notes here and there, things quickly fell into place. With a few clicks of the mouse, and using the same technique as on the bass synth, I had a MIDI file that followed the vocal melody perfectly.

Waves Morphoder.It was fairly trivial to configure the plug-in once I had the MIDI — it involved placing instances of the plug-in on both the original audio and MIDI and instructing the plug-in which MIDI channel to follow. After playing with few options in the Morphoder plug-in, we had pretty much nailed the sound we were looking for. (I like to think that, if I’d been working with a new band, they’d have regarded me as some kind of audio wizard at this point, but Daniel has seen enough of these situations to know it’s not always this quick and simple!)

Waves Morphoder.It was fairly trivial to configure the plug-in once I had the MIDI — it involved placing instances of the plug-in on both the original audio and MIDI and instructing the plug-in which MIDI channel to follow. After playing with few options in the Morphoder plug-in, we had pretty much nailed the sound we were looking for. (I like to think that, if I’d been working with a new band, they’d have regarded me as some kind of audio wizard at this point, but Daniel has seen enough of these situations to know it’s not always this quick and simple!)

Clarity & Brightness

Once we’d addressed the performance issues, my biggest challenge seemed to be getting enough clarity and brightness into the track as a whole. With the drums, I was after a really bright, punchy kick and snare, and my DIY drum samples allowed me to achieve this — I was able to add generous amounts of upper mids (around 6-8 kHz) without having to concern myself with cymbal bleed, and I could bring the level of the overheads down in the mix. To get the snare sitting naturally with the kit, though, I had carefully to set up some extra reverb on the close snare channel. This was set with around a 1s decay time and, after removing some frequencies below about 150Hz on the effect return, this worked nicely.

In terms of getting more overall brightness across a mix, I increasingly find a high-quality EQ on the mix bus is a good way of achieving a more commercial sheen, without things becoming too harsh. It’s important to get this processing involved early in a mix, though, so that you mix ‘into’ the EQ (otherwise you’re unpicking your previous mix moves), but it can often mean you need to do less on individual channels. I’m currently getting good results using a Pultec-style EQ in this way, with a small, but broad, boost at 12kHz, followed by more of an ‘air’ style EQ boost.

Softube’s Tube-Tech PE1C EQ plug-in was used to apply a broad high-frequency boost on the mix bus.As the mix progressed, we still really liked the vocoder effect in the chorus, though we spent a little time finding the right balance between the treated and untreated vocal. The tightened rhythm section was sounding punchy and powerful now but, crucially, it retained just enough of the human element to still feel like a band performing. We’d exercised some restraint by leaving the re-recorded guitars in their natural state, along with most of the bass guitar, and I felt that all this gave the song just enough natural movement to make it feel ‘real’.

Softube’s Tube-Tech PE1C EQ plug-in was used to apply a broad high-frequency boost on the mix bus.As the mix progressed, we still really liked the vocoder effect in the chorus, though we spent a little time finding the right balance between the treated and untreated vocal. The tightened rhythm section was sounding punchy and powerful now but, crucially, it retained just enough of the human element to still feel like a band performing. We’d exercised some restraint by leaving the re-recorded guitars in their natural state, along with most of the bass guitar, and I felt that all this gave the song just enough natural movement to make it feel ‘real’.

Final Thoughts

Further contributing to the ‘sheen’ was the Plugin Alliance Maag EQ4 emulation, with the ‘Air’ band boosted a couple of decibels at 40Hz (thus creating a very gentle lift lower down in the audible part of the spectrum).When you’re tasked with helping artists change course in a recording or mix session, it often puts you in some interesting, very influential — if sometimes a little awkward — positions. Engineers have often had a great deal of influence over the direction of a project, of course, but with the power we have to manipulate audio now in any DAW, it’s more and more expected by artists that we can perform certain tasks. Being able to quickly tighten, tune and experiment with effects and techniques are prerequisites now for a modern engineer — not for every genre of course, but if we have aspirations to work with a variety of artists, we need to learn techniques to quickly implement ideas on a whim.

Further contributing to the ‘sheen’ was the Plugin Alliance Maag EQ4 emulation, with the ‘Air’ band boosted a couple of decibels at 40Hz (thus creating a very gentle lift lower down in the audible part of the spectrum).When you’re tasked with helping artists change course in a recording or mix session, it often puts you in some interesting, very influential — if sometimes a little awkward — positions. Engineers have often had a great deal of influence over the direction of a project, of course, but with the power we have to manipulate audio now in any DAW, it’s more and more expected by artists that we can perform certain tasks. Being able to quickly tighten, tune and experiment with effects and techniques are prerequisites now for a modern engineer — not for every genre of course, but if we have aspirations to work with a variety of artists, we need to learn techniques to quickly implement ideas on a whim.

Thankfully, it’s fairly easy to learn the techniques described in this article, but the real skill is in knowing how to balance this technology with the live performances and often-evolving ideas and emotions of the artist — they can easily get carried away with a new sound, or technique, but can also be unfairly self-conscious about their own ability. I see it as a producer’s job to help them get the balance right. Speed is also important, so that your efforts don’t impede the creative process. And, in the heat of a session, you need to at least give the impression that you know what you’re doing!

Being able to discuss and understand what the band’s asking for and what you’re doing is also important — I was a musician (well, a drummer...) before I got into audio engineering, and I can clearly remember how important it was that we worked with someone who knew where we were coming from. I’m always mocking one of the engineers at my studio for not listening to, or liking, any music made after 2003! It’s all in good fun, of course, but I’m also trying to make a serious point — you need to have at least a vague idea of what people are referring to when they start talking about bands or artists that you’ve never even heard of.

Thus, one of the little ‘continuous improvement’ tasks I set myself is to listen to the radio, both to ensure I maintain a broad understanding of musical styles and some idea of what’s current. I also like to think about how a certain effect that attracts my attention might be achieved, and that helps when faced with requests to apply such effects on a production.

Featured This Month

SOS regulars the Travis Waltons are centred on the talents of songwriter Daniel Flay and drummer Danny Watts. With two albums under their belt (Your Neck Is Bleeding and Separation Season), they’re currently putting the finishing touches to album number three.