Understand the pitch-changing options in Sonar X1 for better results with your audio.

Transposing digital audio is never easy, and the more you need to transpose, the harder it is to retain fidelity. Yet sometimes pitch transposition is necessary and, fortunately, Sonar X1 offers several methods. Note that this column doesn't cover the MPEX pitch transposition found in previous Sonar versions, as it's not supported in 64‑bit Sonar. The iZotope Radius DSP stretching algorithms (included in both 32‑ and 64‑bit versions of Sonar) are equal or better anyway.

Pitch In Time

Sonar's lowest-quality option is the Cakewalk Pitch Shifter plug‑in. It reminds me of the ADA Harmony Synthesizer (circa 1979), an extremely rare analogue pitch‑transposer (only about 800 were made) that used bucket‑bridge delay-line chips. It had this kind of weird wobbling quality that the Pitch Shifter can, for better or worse, emulate.

As with most pitch-shifters, lesser shifts mean better fidelity. If nothing else, this plug‑in is useful for checking out a 'draft' of what a harmony will sound like. However, you can also get some really strange and radical effects by using the 'wrong' settings. I've outlined some of my favourites.

Pitch Shift amounts between ‑0.1 and +0.1 can produce wonderful chorusing and doubling effects. Adjust the amount of chorused sound with the Wet Mix and Dry Mix controls (typically set for equal amounts). Set Feedback to 0 and, if desired, adjust the Delay Time to add a time difference between the two signals.

The Mod Depth control modulates the delay time; its effect varies greatly depending on the amount of Pitch Shift, Delay and Feedback. Results are unpredictable, so just play with it until you get as close as possible to the kind of sound you want. One of its talents is to add ring-modulator‑type effects if you set the Pitch Shift to +12, Feedback to zero percent, and Delay Time to zero, then vary mod depth between about 13 and 20ms.

You can also create pseudo‑bass parts from guitar, using the settings shown in the screen shot. While you probably wouldn't use it for a final mix, it can serve as a placeholder: mix in some dry signal and you'll get a pretty cool eight‑string bass. The Mod Depth control setting is critical, so experiment. I found that settings around 30ms seem to work best.

The Pitch Shifter is a real‑time pitch transposer plug‑in. The settings shown drop the pitch by an octave to produce a pseudo‑bass sound from guitar.

The Pitch Shifter is a real‑time pitch transposer plug‑in. The settings shown drop the pitch by an octave to produce a pseudo‑bass sound from guitar.

The Acid Test

This is an effective technique for transposing down to about eight semitones or up to three semitones (or sometimes even more), and I'm surprised it's not mentioned more as a viable pitch‑shifting method. You'll simplify matters if you use Acidisation solely for pitch‑shifting and not time‑stretching, so record the part to be transposed after you've established the tempo. Then do the following to transpose using Acidisation:

- Record the part.

- If necessary, slip‑edit the beginning and end to measure boundaries, then, with the clip selected, in the Track View edit menu go to Clips / Apply Trimming to discard any audio beyond the slip‑edited boundaries. Note that you'll need to know the part's exact length in beats.

- Go to Project / Set Default Groove Clip Pitch and specify the song's key.

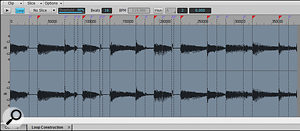

- Double‑click on the clip to open the Loop Construction window.

- Click on the Loop Construction window's Loop button, then enter the number of beats in the Beats field if it isn't already entered correctly (it probably will be).

- Even when not time‑stretching, you still need to make sure that transient markers are in the right places, particularly as you stretch further from the base pitch. For example, you may be able to get decent stretching to three semitones, but with better transient-marker editing, increase that to four semitones. We've covered this process in previous columns but, essentially, you want a marker at the beginning of each transient and at the end of a note that's followed by silence. You can add a marker by clicking in the timeline above the waveform, and move it back and forth by grabbing the 'stem' that appears over the waveform. I generally specify 'No Slice' in the drop‑down menu to the right of the loop button, then add slices manually as needed.

- To transpose, use the two rightmost fields in the Loop Construction window toolbar, for semitones and fine‑tuning.

Transposition will reveal any problems with the Acidisation. Missed transients are pretty obvious as a sort of echo; a flutter on a sustained note can sometimes be fixed by placing an additional marker part-way through the note. It's really a matter of experimentation, so experiment! If you put a marker in the wrong place, remove it with the eraser tool.

There's a really great sound you can get with rhythm guitar parts if you're combining MIDI and audio tracks, as MIDI tracks can be transposed so easily (or you can just create a temporary MIDI track). Here's the scenario: suppose you're recording in E, and have recorded a rhythm guitar part. Mute the audio tracks, then transpose the MIDI tracks down two semitones to D. Now record a doubled guitar part while playing in the key of D.

When you're done, transpose the MIDI parts back to E, and unmute the audio tracks. Now use the Acidisation technique described above to transpose the guitar part you just recorded up two semitones, from D to E. It will have a brighter tone that will add another dimension to the original rhythm guitar part. Similarly, recording a guitar part at a higher pitch and transposing down gives a 'heavier' sound — metal fans, take note.  The clip has had its transient markers edited in the Loop Construction window. Sonar added the ones with the red triangles automatically, while the purple ones were added manually. The clip is 16 beats long and is being transposed up by three semitones.

The clip has had its transient markers edited in the Loop Construction window. Sonar added the ones with the red triangles automatically, while the purple ones were added manually. The clip is 16 beats long and is being transposed up by three semitones.

Go Offline

Using DSP yields the best possible fidelity over the widest possible range, but the reason why is because it's an offline process: you need to apply the transposition to a recorded file, then invoke the DSP and wait for Sonar to crunch some numbers to do the transposition.

To transpose, click on the clip to select it, then go to Process / Transpose. When the Transpose dialogue box appears, tick the Transpose Audio box, enter the transposition Amount, then choose the transposition Type.

There are five pitch‑transposition algorithms: Solo, Bass, Vocal, Radius Mix and Radius Mix‑Advanced. Solo, Bass and Vocal are designed for monophonic lines, while Radius Mix and Radius Mix‑Advanced are optimised for polyphonic material. However, I've found that, even with solo guitar notes from a hex pickup, the Mix algorithms sound the best (the trade-off is that they take longer to crunch numbers than the Solo algorithms).

Choosing the Mix‑Advanced algorithm adds two more parameters: Pitch Coherence and Phase Coherence. The latter is important mostly for surround, so we can safely ignore it (really, how many of you are recording in surround?). I've experimented with Pitch Coherence and, aside from vocals, haven't yet found source material where it makes a huge difference in sound quality.

The DSP fidelity is so good I've been able to create a really cool and extremely authentic‑sounding 12‑string emulation. I used the hex outputs from a Gibson Firebird X, although any guitar with hex audio outs will work. I recorded each string on its own channel, ending up with six channels of recorded sound. I then cloned the lower four strings (low E to G) to create additional tracks for octave‑shifting, and used the Mix‑Advanced algorithm to transpose these up 12 semitones. I was amazed at the sound quality, even when transposed that high.

Even better, I could delay or advance the octave string clips in time to emulate different 12-strings. With Rickenbackers, a down strum hits the octave string first, then the standard tuning string. With a Fender 12-string, it's the opposite. Adding about a 25ms differential between the octave and standard strings emulates the time difference between hitting these strings. (For the high-E and B tracks, I cheated and used a chorus to create the 'doubled string' sound.)

The Transposition dialogue box is set up to transpose up one octave, using the Mix‑Advanced algorithm. The end result will be a 12‑string emulation, as described in the text.So why not just record a 12-string? Several reasons. The Firebird X has a piezo‑based acoustic patch that's quite wonderful, and I don't have an acoustic 12-string. Furthermore, it's easy to do alternate tunings; you can do tricks like Nashville tuning electronically, or drop some strings down an octave while bringing others up — or do both, and get something like an 18‑string guitar. The sound is huge!

The Transposition dialogue box is set up to transpose up one octave, using the Mix‑Advanced algorithm. The end result will be a 12‑string emulation, as described in the text.So why not just record a 12-string? Several reasons. The Firebird X has a piezo‑based acoustic patch that's quite wonderful, and I don't have an acoustic 12-string. Furthermore, it's easy to do alternate tunings; you can do tricks like Nashville tuning electronically, or drop some strings down an octave while bringing others up — or do both, and get something like an 18‑string guitar. The sound is huge!