A dodgy snare recording was just one of the problems facing Rob O'Neil at the mixdown stage, so the SOS team visited his home studio to help him sort things out.

Rob O'Neil is both a solo performer and a front man with his band Taxi, which comprises Matt Woosey on guitar, James Elliot Williams on drums, and Rob himself on bass and vocals. When Rob plays solo, the acoustic guitar is normally his weapon of choice, and when recording with the band, Rob's brother Bruce occasionally furnishes some fine piano parts while Rob overdubs acoustic guitar. They're a good band, with some great original songs, and they've supported major artists and played at serious venues, including the university tour circuit, The Rock Garden, and the Glastonbury Festival. When not playing, Rob has been known to do acting work and has turned up as an extra in several episodes of Casualty. Given his band's line-up and his traditional songwriter's approach to music, it's no surprise that Rob uses his computer-based studio more like a traditional 'audio only' setup.

Assessing The Mixes

When we arrived at Rob's Worcestershire-based studio, he explained that he'd been on a bit of a fitness regime so we were offered plain digestive biscuits rather than chocolate ones. I mention this only to ensure that you don't take this as some kind of precedent! Rob has what might be considered a typical bedroom studio, based around a Windows PC running Steinberg Cubase SL and augmented by a couple of synth modules and a keyboard. His main PC system had developed a fault when we visited, so he'd transferred everything over to his laptop, which was coping fine. He has one main vocal mic, a Rode NT1A cardioid capacitor model, and for monitoring he has Tannoy Reveal Actives set up on stands. While Rob enjoys producing his own material, recording a band with a full drum kit in a bedroom studio is not a practical option, so for his last project he used a small commercial studio to record the electric guitar, rhythm section, and vocals as a live take, then brought the WAV files back to his studio where he overdubbed the remaining parts before mixing them. The stereo imaging was being compromised because Rob hadn't angled his speakers in towards the monitoring position, so Hugh quickly remedied this.

The stereo imaging was being compromised because Rob hadn't angled his speakers in towards the monitoring position, so Hugh quickly remedied this.

Although the performances were good and the songs well arranged, the mixes sounded somewhat congested and lacking in detail, which Rob first put down to the tracks needing mastering. However, once we arrived at his studio, it turned out that we could make more of an improvement by helping with the mixing. As always, the first job was to listen to a commercial recording played over the studio monitors to see how the room behaved. The room was 'L'-shaped and fairly small, and to help deaden the sound Rob had stuck carpet to most of the surfaces. Normally this isn't a good idea, as carpet only absorbs high frequencies, which can leave the room sounding quite dull or boxy. In this case, however, the presence of some plasterboard walls (which acted as ad hoc panel traps), a large window area, and the studio furniture helped to negate the potential ill effects of the treatment, and the general sound was quite workable.

However, the speakers were placed to fire straight down the room, and sitting in front of the computer screens to mix put the listener so far off-axis from each speaker that the stereo imaging was very poor and unstable. All we had to do, though, was turn the speakers in slightly to face the mixing chair and the imaging improved enormously. We also noticed a slightly bass-light area in the centre of the room. Although proper bass trapping may help to improve this, it wasn't a serious problem as long as we avoided sitting in the middle of the room while mixing!

Rob was using a Mackie 1402VLZ mixer for monitoring, where the output from Cubase was being fed into two mixer channels panned left and right. His monitors were then fed from the main stereo outs. We suggested that he instead run the output from Cubase into the two-track returns on the mixer and then select those inputs as the monitoring source. Of course his speakers would need to be connected to the control-room monitoring outputs on the Mackie mixer rather than to the main outputs, but this only meant changing the XLR cables for balanced jacks. The advantage of this setup is that the main mixer channels, via the main stereo out, become available for recording into Cubase at the same time. Furthermore, as the two-track return has no EQ, the simpler signal path should make for more accurate monitoring. Rob had been routing the output from his computer through a channel pair of his small Mackie mixer in order to monitor the signal through the mixer's main outputs. However, this approach put more electronics into the signal path than necessary, and also made it more difficult to use other channels for recording. The solution was to re-patch the computer's outputs into the Mackie's two-track tape return, feeding the monitors from the mixer's control-room outputs instead.

Rob had been routing the output from his computer through a channel pair of his small Mackie mixer in order to monitor the signal through the mixer's main outputs. However, this approach put more electronics into the signal path than necessary, and also made it more difficult to use other channels for recording. The solution was to re-patch the computer's outputs into the Mackie's two-track tape return, feeding the monitors from the mixer's control-room outputs instead.

First off, Rob played us a mix of one of his songs, and this did indeed sound a bit middly and congested, though the balance was pretty good. Rob said that his method of mixing was to treat each sound in isolation until it sounded as good as possible, then balance the sounds in Cubase. However, as you may have discovered if you've tried it, this approach doesn't always work as well as you might expect. The important thing is how the sounds work against each other in the mix, not how they sound in isolation. When checking individual sources prior to mixing, it is worthwhile correcting any obvious EQ problems, but you should leave the creative tonal adjustments until a rough mix is achieved, as you're almost certainly going to need to make changes then.

Salvaging A Drum Recording

Rob's job was further compounded by the drum sound the studio had achieved. They had used a conventional pair of overheads augmented by a kick mic and a further mic placed near to the snare and hi-hat. While the overhead mics sounded OK, the snare-drum mic was producing an extremely boxy sound with virtually no top end, almost as if the mic had been facing the wrong way. I don't know what had gone wrong in the original recording — although the snare mic sounded as dull as ditch water, the snare sound in the overheads was bright and natural. The close-miked kick drum was also ringing and lacking in definition, with quite a lot of spill, and it sounded as though the mic was placed in front of the kick drum rather than inside.

Sorting out the drum sound was clearly going to be our greatest challenge, as the other tracks sounded perfectly usable, including the overdubs Rob had done at home. Had we had a decent enhancer plug-in, I would have used that to add some snap back into the snare drum, but I ended up using a 115Hz cut combined with a fairly aggressive 6.3kHz boost. I then gated the track to clean up the spill from the other drums, and to lose the ring. This was all done using the Cubase plug-ins, as they were pretty much the only ones Rob had. In isolation, the sound still wasn't very bright, and the gating effect wasn't entirely natural, but checking it in combination with the overhead mics showed that the composite sound wasn't that bad. There was a reasonable amount of snare 'snap' in the overheads anyway, and the tweaked close mic helped add in some welcome body and weight.

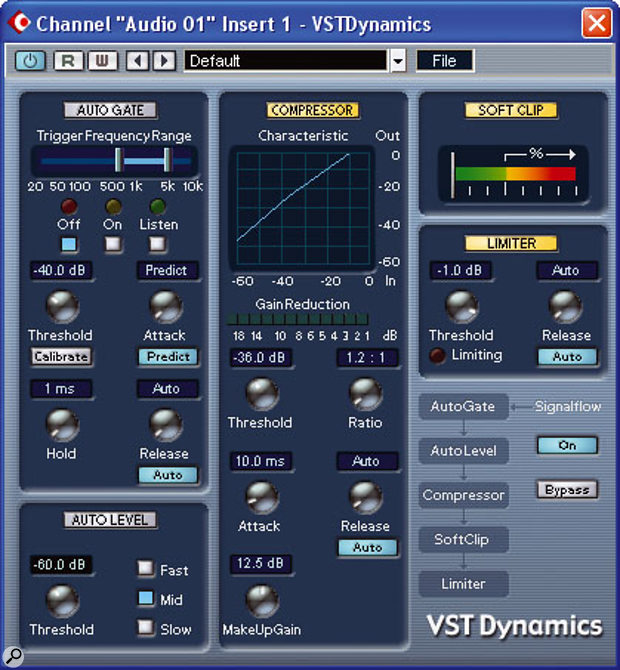

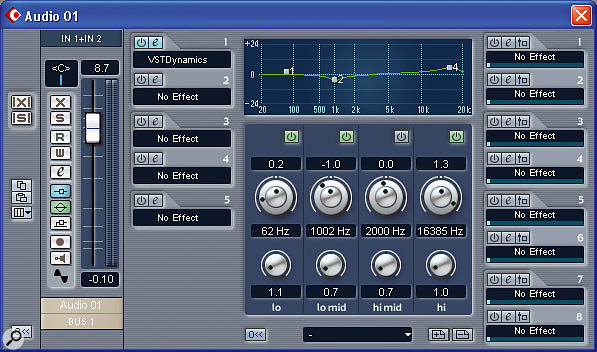

Although the overhead drum mics sounded good, the snare and kick close-mic signals had been badly recorded, and needed some heavy processing to salvage something usable — here you can see the settings used.

Although the overhead drum mics sounded good, the snare and kick close-mic signals had been badly recorded, and needed some heavy processing to salvage something usable — here you can see the settings used.

The drums were left mainly dry, but a little Cubase 'Ice' reverb — a nice bright plate-like sound — was added to the snare track, just enough to give the impression of playing in a larger space, but not enough to wash out the sound. For the kick drum, we settled for a 250Hz cut to try to take out some of the boxiness, coupled with a 5.5kHz boost to try to improve the definition. Again gating was used to take out the ring. Problems can arise when mixing the overhead mics and the close mics together, because small phase differences caused by the spacing of the mics can compromise the low end. We solved this simply by rolling off some low end from the overhead mics, adding a little gentle air EQ at 12kHz or so, and relying on the two close mics to add the weight.

The two overhead mics were presented as separate mono tracks, rather than as a stereo pair in Cubase, so we copied the EQ settings from one channel to the other to ensure they remained properly matched. Whereas Rob had balanced the close-miked sounds and then added a little overhead to fill in the cymbals, we worked the other way round using the overheads as the main sound and the close mics just to underpin the kick and snare. To our ears, this gave a much more open and transparent drum sound. Finally, the amount of snare reverb was adjusted to give the right subjective reverb level when the rest of the drums were playing.

Mixing The Overdubs

The next thing to add was the bass guitar, which had been DI'd directly into the desk. In isolation, this sounded fine, but tended to lack definition when the remaining tracks were brought up. This is very common with DI'd bass, and the instinctive response is to add more low EQ to the sound to bring out the bass, but that tends to be counterproductive as it means you have to turn the overall track level down to maintain headroom. The part of the bass-guitar sound that you actually hear in a mix is more likely to be between 200 and 300Hz (which is why you can still hear the bass guitar on a small transistor radio with no low end) and that's the area that gets reinforced when you use a bass guitar amp and speaker rather than DI'ing. Our solution was to compress the bass slightly to even out the level, then boost it at 255Hz to give the sound the ability to cut through. Rob wasn't sure about this when he heard the bass track in isolation, but with the rest of the mix up and playing, he agreed that it worked much better.

Rob's acoustic guitar was one of the other mainstays of the mix, but he'd again EQ'd this in isolation, with the result that it sounded rather like a solo acoustic guitar part. When used within a mix, the acoustic guitar doesn't need that big low end — it just gets in the way — so again we added mild compression to keep the level even and applied a fairly wide cut at 250Hz to take some of the weight out of the low end. There was also a hint of harshness in the sound which was dealt with by cutting at around 3kHz. This left us with a thinner sound with more zing to it, which sat well in the mix without getting in the way of the bass guitar and kick drum.

Rob's lead vocal was pretty good already, so that was treated with just very light compression and a touch of 12kHz 'air' EQ and light reverb to freshen it up. However, when vocals are going to be recorded in a bedroom studio such as his, the result can generally be improved by using our regular trick of hanging a duvet or sleeping bag behind the singer's head to reduce the amount of reflected sound getting back into the mic. In practical terms, this reduces the effect of the room acoustic on the sound, and even though a little room coloration may sound OK to start with, as soon as you add compression it tends to get emphasised. The less room sound you pick up, the cleaner the vocal recording will be.

As a rule, it's best to try to avoid radical EQ with vocals, as it can lead to a very unnatural or coloured sound, especially with simple plug-in equalisers. It also helps to be sparing with less sophisticated reverb plug-ins, as they have a habit of seeping into all the spaces in a mix if you use too much. This is often not fully appreciated unless you've had a chance to hear a really good reverb, so upgrading to either a mid-price hardware reverb or a DSP-powered effects card/box is a good way to upgrade if your system doesn't have the horsepower to run one of the new convolution-based reverb plug-ins.

An existing electric guitar part was left much as it was, but re-balanced lower in the mix, and the guitar solo — which was on a separate track — was tweaked to make it sound more part of the band and less like an overdub. Rob had added some big delays of around three and four seconds respectively to the left and right channels, as well as some fairly dramatic EQ, but the guitar sound had a slightly rough edge to it and the big delays made it sound quite disembodied. As the flavour of this song was more 'West Coast rock', something more conservative was required. The guitar tone was tamed by applying a 92Hz cut to thin out the bottom and a 6.9kHz cut to smooth out the top. The left and right delays were reduced to around 300ms and 400ms, resulting in a sweeter, better-integrated guitar tone.

Last of all, a piano track, played by Rob's brother Bruce, had a strong left-hand bass component that tended to fight with the bass guitar and kick drum, so some low cut was applied to keep it out of the way. Then we balanced up the tracks and retired to the landing outside the bedroom studio to listen to the result from outside the door. This trick of listening outside in the passageway never fails to show up balance problems, after which we made a few further minor level adjustments and then bounced the song to a stereo file that we could use as a 'guinea pig' for some mastering experiments. We also did some straight comparisons with Rob's original mix, which showed we had improved the overall transparency and clarity of the mix, even though the snare drum sound was never going to be great.

After working on the mix, Paul worked with Rob on selecting suitable mastering processing — the final settings can be seen in the screenshots.

After working on the mix, Paul worked with Rob on selecting suitable mastering processing — the final settings can be seen in the screenshots.

Mastering Suggestions

Rob asked us if it was OK to use mastering processors at the mixing stage, and while there's no technical reason not to do this it doesn't really help achieve one of the main aims of mastering, which is to help the different songs on an album work together both tonally and in terms of level. It's far better to mix with no overall processing, then compare the finished tracks that will be used on an album before processing them to produce the same 'family' sound. Other considerations such as adjusting relative balance, and limiting to achieve extra loudness, can also be addressed at this stage. Personally, I wouldn't try to master anything serious in a small bedroom studio using nearfield monitors, but if you check your mixes on other systems, you can achieve some worthwhile results and gain experience at the same time.

Neither are the basic plug-ins that come with 'light' sequencers particularly great sounding for mastering, but used with care they can help apply a little polish to mixes. On this particular mix, we demonstrated the gentle compression that can be achieved by using a very low compression ratio of around 1.2:1 combined with a low threshold (around -35dB relative to digital full scale) to produce just a few decibels of gain reduction across the entire dynamic range of the mix. This was followed up by the Cubase limiter and soft clipper, and the compressor makeup gain was adjusted to give brief limiting on signal peaks. I didn't feel the Cubase limiter had good enough metering to do this job in any serious capacity, but we managed to get a lot more subjective level without obviously compromising the sound. There is no standard EQ for mastering, as you just have to do what the song needs, but we demonstrated the clarifying effect of broadband 'air' EQ in the 12-14kHz range as well as the ability to add 'thump' by applying just a little boost at between 80Hz and 90Hz.

Although Rob had made good recordings and clearly has a good ear for balance, his mixes had run into trouble because he was trying to optimise sounds in isolation before mixing them. The studio drum sounds he had to work with didn't help either. While you can make general adjustments before mixing, you are nearly always going to have to change your EQ settings once everything else is playing. The other thing that helped us improve the mixes was using EQ to prevent sounds colliding with each other, especially in the upper reaches of the bass register, where things can easily get messy. This kind of attention results in a much more open-sounding mix with far greater clarity — as Rob himself commented. Rob had also been using some over-dramatic EQ and compression treatments to shape his individual tracks, but readjusting the EQ settings made a big difference, and most of our more 'dramatic' EQ settings involved cut rather than boost, as the ears perceive that as more natural. Rob also tried too hard to push the guitar solo out front by making it loud with lots of echo. By re-equalising it and adding a more restrained amount of echo, then pulling it back in the mix a bit, it sounded as though it belonged to the band again and didn't sound any smaller or less powerful for it.

Rob's Comments

"Having the SOS team visit was extremely useful in several respects. Firstly, the band and I didn't listen back to the original studio recordings in enough detail, just a rough monitor mix, so we didn't pick up on the fact that the kick and snare sounds were extremely poor — as Hugh and Paul pointed out, they were being concealed by the overheads, so no-one noticed at the time. We were aiming to capture a performance, which took precedence over sonic quality, though with hindsight we should have had both in mind equally. However, the budget didn't allow for too many takes — a maximum of two shots at each song!

"Having the SOS team visit was extremely useful in several respects. Firstly, the band and I didn't listen back to the original studio recordings in enough detail, just a rough monitor mix, so we didn't pick up on the fact that the kick and snare sounds were extremely poor — as Hugh and Paul pointed out, they were being concealed by the overheads, so no-one noticed at the time. We were aiming to capture a performance, which took precedence over sonic quality, though with hindsight we should have had both in mind equally. However, the budget didn't allow for too many takes — a maximum of two shots at each song!

"Observing the remix was extremely informative. I had approached it wrong by trying to get each individual sound as good as possible in isolation first. I now see the process more like a jigsaw — the pieces don't fit if you have segments that overlap. Removing elements from each of the sounds really gave the mix room to breath, as though you could see daylight between the instruments. I thought it sounded more 'live' than my mix, more real. I'd tried to use low frequencies and volume to give it power, but had achieved the opposite!

"One great tip was how to make the lead guitar solos sound bigger. Having applied big delays to try giving it that stadium feel, Paul and Hugh made it more subtle, explaining that you can get the same effect of making it sound like it's in a bigger space just by how you EQ it and place it in the mix. Overall the power didn't suffer for reducing the bottom end on things like the bass guitar. The whole mix became clearer, sweeter, and more punchy; the guitars weren't fighting for space; and the vocal sounded really full and louder, but still part of the band.

"Once the mix was lighter and more free of overlapping sounds, balancing the track was much easier, and all the instruments seemed to slot into place where I wanted them to do so, without any persuasion required. From now on I'll work the other way round, do a rough mix first, then start throwing out elements that are occupying the same frequency band before mixing again. It all goes to show how much skill and experience is needed when mixing — I've always concentrated on writing and performing, and engineering is equally difficult to master. I'll apply the techniques the team showed me and get more engineering practice done!"