Our Mix Rescue expert dips his toes in the Studio SOS waters this month, as he visits a reader's studio, sorts out his monitoring and takes him through strategies to improve his mixing.

Like a lot of SOS readers, Barry Martin has his own home studio setup that he's keen to master. Recently, however, he'd begun to feel that his progress had hit a bit of a brick wall, so posted on the magazine's web forum asking for some one‑on‑one tuition. The catch, however, was that he wanted to learn using his own equipment, rather than going to someone else's studio, and he'd had trouble finding anyone to fit the bill. Fortunately, this is the kind of thing that we at SOS do all the time, so I asked him if he fancied a visit for the Studio SOS column, in the hope that any advice thrown up by the session might benefit other readers too.

Mike helped Barry remove much of his existing thin acoustic foam, which was having little positive effect on the room acoustics.

Mike helped Barry remove much of his existing thin acoustic foam, which was having little positive effect on the room acoustics.

Monitoring Issues

Listening to a couple of Barry's mixes before the visit, I suspected that monitoring problems were one factor holding him back — the low‑end levels were quite inconsistent between different tracks, and balances occasionally seemed out of kilter. He'd already applied some acoustic foam squares here and there, but they were thin, so of no real use below about 1kHz. Auralex kindly supplied us with some thicker replacements, as well as some large corner wedges (which absorb a little further down the audio spectrum), so my first job after arriving on site was to help Barry put all that up, a process that has frequently been described in previous Studio SOS columns.

However, although this foam treatment took some of the edge off the early‑reflection problems (reducing phasing and stereo‑blur artifacts), I knew it wasn't going to do much about low‑end room resonances, of which there were plenty in Barry's 3 x 4m studio — a quick blast of some low‑frequency sine waves confirmed than the low end of the spectrum still had a good share of resonant lumps and bumps in it, and the response also varied considerably as you moved around the room. Ideally, I'd have liked to put up at least eight Rockwool bass traps, of the kind that Paul White and Hugh Robjohns often construct for their Studio SOS visits, although even then I know from experience that the most you can hope for is an improvement rather than a cure.

Using a small mono speaker for secondary monitoring in a small studio like Barry's can help side‑step many of the problems of uncontrolled low‑frequency reflections.However, as I explained to Barry, this isn't actually the end of the world — it just means that you have to think a little bit laterally when it comes to judging the low‑end balance of your mixes. My first tip was to get hold of a good spectrum analyser (such as Voxengo's SPAN or Roger Nichols' Inspector), as that can be a useful reality‑check (although only once you get to know how it responds to commercial tracks!). Walking around the room sometimes helps too, as it can allow you to mentally 'average' the frequency‑response peaks and troughs to an extent. I also recommended that Barry get hold of an Auratone‑style single‑driver mini‑monitor (my top tip being Avantone's Mix Cube) to assist with mix balancing, as this kind of mono monitoring tends to be much more resistant to room problems than typical stereo nearfields.

Using a small mono speaker for secondary monitoring in a small studio like Barry's can help side‑step many of the problems of uncontrolled low‑frequency reflections.However, as I explained to Barry, this isn't actually the end of the world — it just means that you have to think a little bit laterally when it comes to judging the low‑end balance of your mixes. My first tip was to get hold of a good spectrum analyser (such as Voxengo's SPAN or Roger Nichols' Inspector), as that can be a useful reality‑check (although only once you get to know how it responds to commercial tracks!). Walking around the room sometimes helps too, as it can allow you to mentally 'average' the frequency‑response peaks and troughs to an extent. I also recommended that Barry get hold of an Auratone‑style single‑driver mini‑monitor (my top tip being Avantone's Mix Cube) to assist with mix balancing, as this kind of mono monitoring tends to be much more resistant to room problems than typical stereo nearfields.

In order to demonstrate the reasons for this, I connected up my own little Canford Audio Diecast Speaker to Barry's system, feeding it from the headphone output on his Mbox 2 audio interface via a special 'stereo‑to‑mono' adaptor lead — you can find instructions for making one of these for yourself at http://koo.corpus.cam.ac.uk/mixerton/articles/monocable. Playing a few musical excerpts from my own reference CD, it was clear that the single small speaker interacted much less with the room's resonance modes than did the nearfields, and it also provided much more stable imaging (which makes for easier balancing) for important centrally panned instruments. The latter was especially apparent because the pair of Fostex PM2s that Barry was using had been spaced too far apart in order to accommodate his computer's dual flat‑screens, so the 'phantom' central images were particularly unstable.

I suggested that the speakers might be better placed on wall brackets above the screens to allow narrower spacing, and Barry said he'd see what he could do there. I also noticed that the speakers didn't present much inertia, recoiling quite easily when subjected to my deeply scientific 'poke them with a finger' test. Inertia is a good idea when you want accurate bass reproduction, because otherwise the speaker itself will tend to wobble around in response to large low‑frequency woofer‑cone excursions, distorting the audio. A benefit of fixing the speakers to the wall, in Barry's case, is that it might also anchor them more solidly, assuming that sturdy brackets were employed.

Another thing I mentioned to Barry was that a top‑of‑the‑range pair of open‑backed headphones might also be a sensible purchase in his situation, to provide a reasonable perspective on the mix, uncoloured by room acoustics considerations. It's amazing how well you can mix on headphones using models such as Sennheiser's HD650 or Beyerdynamic's DT880 Pro, and this can help to offset some of the nearfield monitoring unreliability that's inherent in most real‑world budget studio setups.

Examining The Mix Settings

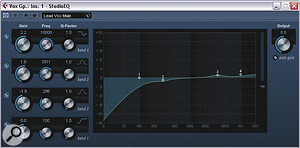

At first glance this Barry's lead vocal EQ appeared fairly sensible — but it turned out that it was just a preset and didn't actually suit the needs of the track.

At first glance this Barry's lead vocal EQ appeared fairly sensible — but it turned out that it was just a preset and didn't actually suit the needs of the track.

In order to tailor my advice to Barry's music, I suggested that we examine one of his own Cubase mix projects, and at a first glance his EQ usage seemed fairly sensible. For instance, high‑pass filters were in evidence for many of the tracks, something that's vital for small‑studio work, where you can't always rely on your monitoring to alert you to sub‑bass rumbles and general low‑end 'rubbish'. Most of the frequency graphs also showed the fairly restrained settings that I'd expect of mix processing — in that there was nothing much beyond 6dB of gain or attenuation.

However, on closer inspection, it turned out that these settings were presets from Cubase's internal library. Barry was the first to admit that he lacked confidence with using EQ, so it's easy to see how the temptation to fall back on the presets arose, but EQ presets are basically useless for mix purposes — because one of the main purposes of mix equalisation is to deal with frequency interactions between the different tracks in your arrangement; arrangements vary a great deal from song to song, and EQ presets take no account of this.

I also raised an eyebrow upon discovering an instance of Cubase's GEQ30 graphic EQ on one of the vocal parts. Graphic EQ isn't usually very well suited to mixing tasks, in my view, because it tends to encourage you to process rather narrow frequency regions: narrow boosts rarely sound good, whereas narrow cuts aren't tremendously useful unless you can aim them more precisely at troublesome resonances.

The biggest processing problems to my mind, though, were to be found in the internal mixer of XLN Audio's Addictive Drums, which Barry was using to supply drum parts. This was piling on a heap of EQ and compression for each of its individual 'virtual mic' channels (again as part of the instrument's presets), but it seemed to me that the settings didn't really relate to Barry's song and were over‑hyping the sound — so I suggesting pruning them back fairly hard in search of a more natural sound.

Barry's effects were fairly minimal, with a couple of barely used send‑effect reverbs, and a clear problem for me was that these sounded over‑done, even though the track as a whole didn't really gel properly. While investigating the send channels I also noticed that he'd popped an instance of the Waves multi-band limiter into the main Cubase mix outputs. Although I'm not shy of master‑bus EQ or compression per se, I recommend that most people steer clear of multi‑band dynamics processors at mixdown, as they're much more complex beasts which can make mix‑balancing feel very confusing.

Given the range of different issues I'd encountered during my reconnaissance, it seemed to me that advising Barry on the general framework of his mixing activities would be more useful than spending too much time focusing on tweaks to the original mix version. So I duplicated the project file, removed all the processing plug‑ins, and spent our remaining time together showing him how he might go about building up a better mix from scratch.

Better Software Drum Sounds

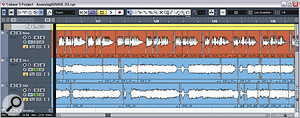

Splitting the kick and snare MIDI parts to separate tracks allowed these parts to be processed individually with Cubase's MIDI Modifiers plug‑in, making them more consistent in the mix.

Splitting the kick and snare MIDI parts to separate tracks allowed these parts to be processed individually with Cubase's MIDI Modifiers plug‑in, making them more consistent in the mix.

To start with, I detailed some of the advantages of introducing tracks to the mix in order of sonic importance — it's easier to deal with frequency‑masking issues between instruments one at a time, and also encourages you to use higher‑quality (and therefore more CPU‑hungry) plug‑ins on the most important instruments. We decided that we should therefore start with the drums (a common choice when mixing rock music such as Barry's) and so faded up the Addictive Drums instrument, removing all internal EQ and dynamics processing from its individual mic signals so that we could concentrate on getting the best raw sound.

As I suspected, there was a great deal that we were able to do before any need for processing arose. Choosing the right drum sound was important, of course, but so was adjusting the MIDI trigger data to get the best out of it. The same drum can sound very different depending on how hard it's hit, and there's also no point in processing a drum to death to deal with performance unevenness which MIDI editing can solve much more transparently. I ended up splitting out the MIDI data for both the kick and the snare parts, and was able then to insert Cubase's MIDI Modifiers plug‑in over those MIDI tracks to make the playing appear more consistent and commercial.

It was also crucial to achieve the right balance of all the instruments in the overhead and room mics, because these mic signals form the basis of any natural‑sounding drum recording. Fortunately it's possible to adjust this easily with each instrument's Overhead and Room level controls, and it was a real eye‑opener how much this simple step improved the overall sound of the kit — especially the snare, which always tends to sound best when heard through the overhead mics. Once the kit instruments were balancing sensibly in the overheads/room signals, we could then fade up each of the close‑mic signals as required to add in more punch and hit definition, and the result was a decent kit sound which required very little processing at all. In a lot of respects this mirrors the realities of recording and mixing live drum kits: the more suitable the sound of the instrument and the better the balance captured through the mics, the less work you're likely to have to do to fit things into the mix later on.

To EQ Or Not To EQ?

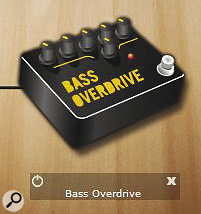

In place of the former preset lead‑vocal EQ, a more appropriate tonal treatment in Barry's track turned out to involve a notch at around 8kHz (to tame a nasty microphone resonance) and a small dip at 350Hz, combined with some parallel distortion from the Bass Overdrive stomp‑box model in Line 6's Pod Farm.

In place of the former preset lead‑vocal EQ, a more appropriate tonal treatment in Barry's track turned out to involve a notch at around 8kHz (to tame a nasty microphone resonance) and a small dip at 350Hz, combined with some parallel distortion from the Bass Overdrive stomp‑box model in Line 6's Pod Farm.

Once the drums were in place, we followed them up with the bass, which didn't actually warrant any EQ at all, just some slow compression from Cubase's Vintage Compressor, to keep it at a consistent level. The two rhythm guitars needed only slightly more processing: mostly just some high‑pass filtering to keep the low end clear for the bass, a broad 2dB EQ peak at 1.4kHz to increase the note definition, and a little compression to one of the two parts so that its dynamic range matched the other more closely — an important consideration given that Barry wanted to pan the guitars to opposite sides of the stereo spectrum to widen the mix's stereo image.

So far, we'd needed very little EQ to speak of — and in fact you often don't need that much if you've chosen sounds you like and there's lots of space in the mix. I had, however, made a point of switching back and forth between the nearfields and the mono speaker repeatedly during the process, so that Barry could hear how the former supported tone and quality judgements, while the latter focused more critically on balance issues. This comparative monitoring clarified many of our mix decisions, highlighting for instance when kick‑drum EQ was required — although the drum balanced fine on the mono speaker, it seemed weak in the nearfield balance, because the low end wasn't coming through powerfully.

The vocals needed more processing, though, because not only did they sound a bit thin and uninspiring, but they also conflicted with the guitars in the frequency spectrum. A few moments twiddling the EQ was enough to show Barry that it wasn't actually that good at altering the track's subjective tone, so I instead applied another process which often yields greater rewards in this department — the common rock & roll trick of parallel distortion. It's not that EQ has no role to play in making a sound more pleasant to listen to (it was useful to scotch a harsh 8kHz vocal‑mic resonance, for example), but it's very easy to overprocess if you try to use EQ for things it's not good at.

That said, I also had the opportunity to illustrate where EQ really comes into its own: in dealing with the inevitable frequency conflicts and pile‑ups which occur when parts are combined in an arrangement. For instance, the strong guitar 'presence' frequencies in Barry's mix, around 4kHz, were masking those same vocal frequencies, pushing the singer back into the balance. A couple of decibels of peaking EQ cut on the guitars offered a simple and effective solution, making the vocal tone appear clearer. In addition, a build‑up of energy around 350Hz in the vocal, guitar, and bass parts was making the mix feel a bit muddy overall, so another couple of decibels of cut in this region for both the upper parts proved beneficial.

One thing that surprised Barry was that my EQ consisted almost entirely of cuts, rather than boosts, so I explained to him the rationale behind this. The biggest reason to avoid boosts is psychological really, because it makes it trickier to fool yourself into thinking you've improved a processed instrument simply because your boosts have made it louder (louder sounds always seem more impressive). However, boosting can also be bad from a sonic perspective (especially when using the CPU‑light EQ typically built into most sequencers), because any unwanted processing side‑effects will usually be strongest where the most EQ gain is being applied. By cutting, you'll normally put those artifacts into areas of the frequency spectrum that are less important to the sound you're processing. It takes a bit of concerted brain‑washing to get yourself into the habit of cutting rather than boosting, though, so few newcomers to mixing seem to take this useful technique on board.

Making Reverb & Delay Effects Work

Mike set up a version of the classic pitch‑shifted delay stereo widening patch for Barry using Waves Doubler.

Mike set up a version of the classic pitch‑shifted delay stereo widening patch for Barry using Waves Doubler.

Once we had a basic balance up and running, I added in a few stalwart mix effects to show Barry how these could help blend and warm the final mix. A small room ambience was first in line: starting from a preset in Lexicon's native reverb plug‑in, I pulled down the reverb time to its minimum, and then added different amounts of it to all the different parts in an attempt to blend everything together and set their front‑back positions in the mix. With rough effect levels set, I then filtered the reverb's return channel to keep the low end clear of muddiness, and to reduce a little of the reverb's high end, thereby reducing its audibility as an artificial effect. Although most reverbs have loads of parameters, you rarely need to delve into them nowadays — as long as you take care in selecting a preset, you can usually get by with just tweaking the reverb length, send levels, and return‑channel EQ.

Another meat‑and‑potatoes effect I dialled in was a simple quarter‑note delay patch to increase the sustain of the vocal parts. By virtue of being tempo‑sync'ed this usually sinks into the mix pretty well, but I usually help it along with another dose of return‑channel EQ. In this case I also sent from the delay return to my ambience reverb too, in order to widen the delay repeats and push them into the background. An instance of Waves Doubler completed the send‑effects menu, implementing a version of the classic pitch‑shifted delay stereo‑widening patch that's so effective in making lead vocals appear larger-than-life: short delays of 11ms and 13ms, shifted by five cents down and up respectively.

Once all these were running, I passed on to Barry a couple of useful little safety checks which are good for refining your effect levels. Firstly, just toggle the effect return's mute button — if you can get the levels so that you only really notice the effects when they disappear, then that's usually about right for general mixing purposes these days. Secondly, try muting the most imposing instruments (drums, bass, and vocals usually) in various combinations, because this makes it a lot easier to tell if effects levels are appropriate for your less prominent backing parts.

At The End Of The Day

By the time the clock had caught up with us, we'd managed to put together a pretty solid static mix. More importantly, though, Barry was more confident in his studio monitoring setup, and was up to his eyeballs in new ideas to explore. Hopefully some of them will also help you in your own studio too!

A Stitch In Time

Before I began reworking Barry's mix in earnest, I took the opportunity to demonstrate to him how tightening the timing of the rhythm section could make the mix appear more commercial‑sounding.

Before I began reworking Barry's mix in earnest, I took the opportunity to demonstrate to him how tightening the timing of the rhythm section could make the mix appear more commercial‑sounding.

It only took about 20 minutes to line up the bass and guitar parts more with the drums, but the difference to the blend and punch of the mix was palpable, which meant we didn't have to use as much processing for these purposes later on.

Reader Reaction

Barry Martin outside his studio. Even with a small room like this, some strategically placed foam of the right type can make a big difference to the listening environment — and leave you to focus on making music!Barry Martin: "I'd been on the SOS forum many a time pleading for local audiophiles to come and help me improve my studio technique — because I wanted to wring the best out of my nice equipment, but still lacked the knowledge to deliver satisfying results. After Mike's visit to my humble little studio, my head is still spinning from all the gems he disclosed during the few hours we spent together. I can categorically say that the expense of a full English breakfast for Mike and myself at my local greasy spoon was very much worth the investment!

Barry Martin outside his studio. Even with a small room like this, some strategically placed foam of the right type can make a big difference to the listening environment — and leave you to focus on making music!Barry Martin: "I'd been on the SOS forum many a time pleading for local audiophiles to come and help me improve my studio technique — because I wanted to wring the best out of my nice equipment, but still lacked the knowledge to deliver satisfying results. After Mike's visit to my humble little studio, my head is still spinning from all the gems he disclosed during the few hours we spent together. I can categorically say that the expense of a full English breakfast for Mike and myself at my local greasy spoon was very much worth the investment!

"First off, the changes we were able to make to the sound of the room were really quite inspiring (thanks Auralex!), and mixing is now a whole heap easier. Once we'd got the acoustics issues out of the way it was great to be able to turn the virtuoso's visit into a combination of Studio SOS and Mix Rescue — a dream for me. Thanks Mike and SOS for helping me so enthusiastically on my continuing journey of discovery!”