This new four-part series explains all you need to know about creating brass arrangements for a range of genres.

In the ephemeral, here-today, gone-tomorrow world of popular music, it’s good to know there are certain long-standing ingredients which have stood the test of time. One such enduring feature is the classic pop/soul brass arrangement, a musical item that has maintained its relevance, hip-ness and appeal for over half a century.

This Kontakt multi uses two solo instruments from the Chris Hein Horns Vol. 2 sample library. A trumpet sustains patch is layered with a staccato trumpet to strengthen the attack. With both patches set on the same MIDI channel, played short notes produce a staccato effect, while longer notes trigger a sustained sound with a strong attack. In this multi, the same technique is applied to a solo tenor saxophone (operating on a different MIDI channel from the trumpet patches).Though I’m not here to teach history, it’s worth bearing in mind that many of the key features of contemporary brass arranging are based on a musical roadmap established in the 1960s. By the middle of that decade the US soul scene was in full swing, and the charts were jammed with trailblazing tracks by artists such as Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and James Brown. Take a look at the ‘20 Classic Brass Arrangements’ box and you’ll see a chronological list of records from this period which have been highly influential in shaping the development of pop brass arrangement.

This Kontakt multi uses two solo instruments from the Chris Hein Horns Vol. 2 sample library. A trumpet sustains patch is layered with a staccato trumpet to strengthen the attack. With both patches set on the same MIDI channel, played short notes produce a staccato effect, while longer notes trigger a sustained sound with a strong attack. In this multi, the same technique is applied to a solo tenor saxophone (operating on a different MIDI channel from the trumpet patches).Though I’m not here to teach history, it’s worth bearing in mind that many of the key features of contemporary brass arranging are based on a musical roadmap established in the 1960s. By the middle of that decade the US soul scene was in full swing, and the charts were jammed with trailblazing tracks by artists such as Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and James Brown. Take a look at the ‘20 Classic Brass Arrangements’ box and you’ll see a chronological list of records from this period which have been highly influential in shaping the development of pop brass arrangement.

Note that I’m using the word ‘pop’ in its widest sense, meaning the broad sweep of popular music (as opposed to classical, opera, Armenian bagpipe music or Tuvan throat-singing). That obviously covers a huge number of genres, but the ones in which you’re most likely to find soul-based brass nowadays are contemporary R&B, funk, Latin, urban, rap, hip-hop, ska, reggae, blues rock and mainstream pop (apologies for any styles I’ve inadvertently left out). Having said that, I’m not a big fan of musical categorisation, so if you want to add some funky brass to a traditional Tuvan throat-singing piece, go for it — and the best of luck to you!

Brass Tactics

In this article I’ll explain some of the basic musical ideas which crop up in pop brass arrangements, with a view to encouraging you to create hands-on arrangements of your own. For the benefit of those who don’t read music, we’ve included a Logic Pro piano-roll screenshot with each musical example. Those who can read music should remember that a dot written over the top of an eighth note indicates it should be played as a 16th note (this avoids writing in lots of fiddly rests).

Unless you’re in that small minority of musicians who can write out charts and pay session players to record them, you’ll need certain tools to help you: namely, a DAW or hardware sequencer, some decent brass sounds (see the ‘Patch It Up’ section below) and a MIDI keyboard on which to play your ideas. If you don’t play keyboard, a MIDI guitar or wind controller will do, though note that the latter can only play single lines, not chords.

The saxophone is present by default in most pop/soul ‘horn’ sections, whereas its presence in orchestral ensembles is more unusual. Some film and TV composers circumvent the keyboard issue by inputting notes directly on their software sequencer’s score page. Although I’ve heard convincing orchestral mock-ups which were created this way, I don’t recommend it for pop brass writing — this stuff relies, to a large extent, on human feel, and so works best when played on an instrument, rather than via a laboured series of mouse clicks.

The saxophone is present by default in most pop/soul ‘horn’ sections, whereas its presence in orchestral ensembles is more unusual. Some film and TV composers circumvent the keyboard issue by inputting notes directly on their software sequencer’s score page. Although I’ve heard convincing orchestral mock-ups which were created this way, I don’t recommend it for pop brass writing — this stuff relies, to a large extent, on human feel, and so works best when played on an instrument, rather than via a laboured series of mouse clicks.

Playing devil’s advocate, there is another, less labour-intensive way of going about the task: you could follow The Prodigy’s and Sugababes’ lead and sample a brass arrangement from an old record, as these acts did with (respectively) ‘Stand Up’ (featuring the blasting, anthemic instrumental break from Manfred Mann Chapter Three’s ‘One Way Glass’) and ‘Girls’, which makes liberal use of an infuriatingly catchy horns lick from Ernie K-Doe’s ‘Here Come The Girls’. However, unless you have a silver-tongued music-biz lawyer and a pot of cash to appease the original rights holders, it’s best to avoid that route.

A less legally perilous approach would be to buy a sample library of pre-recorded brass phrases and paste them over a backing track in your DAW. Though easy to do and superficially gratifying, that painting-by-numbers approach lacks creativity and tends to put the cart before the horse — you end up trying to make your track fit the phrases, rather than the other way round. Far better to use your imagination, think of some brass riffs of your own and play them into your sequencer, even if you have to do it one bar at a time, at half speed with one finger (no shame in that). At least that way you won’t be regurgitating the same pre-recorded licks as everybody else!

Instrumentation

Pop brass uses a different instrumentation and terminology from orchestral (‘classical’) brass. In the pop world, trumpets, trombones and saxophones are intermingled, with all instruments indiscriminately referred to as ‘horns’. In orchestral circles ‘horn’ means French horn, that complicated, circular piece of plumbing with a large flared horn and protruding mouthpiece. Some modern composers use saxophones in symphonic works, but a traditional orchestral brass section contains only trumpets, trombones, French horns and tubas. This critical difference marks the chief distinction between orchestral and pop brass: lacking the distinctive, reedy, slightly raspy timbre of the saxophone, classical brass has a pure, homogenous and refined tonal quality that has evolved over hundreds of years. By contrast, a pop horn section is essentially a 20th-century invention which, due to the saxes, can produce a more fluid, complex, insinuating and sexy sound.

Contemporary brass line-ups vary in size from a single performer (usually a trumpet, trombone or sax player) to five horns (trumpet, alto sax, tenor sax, trombone and baritone sax). Instrumentation and section sizes vary: it’s not unusual to hear a single horn player playing a jazzy solo over a track, while many bands feature just two players — typical examples include trumpet and sax, trumpet and trombone, and two saxes. Trumpet, alto and tenor sax trios are also common. The only rule we might apply here is to say that a section of more than five players is veering into jazz big-band territory, which is something I’ll look at later in this series.

Patch It Up

As a first step towards creating a brass arrangement, I’d suggest using a trumpet sound, for the simple reason that a trumpet often plays the highest part in an arrangement, and it’s this top line which connects with listeners and gives the arrangement its character. If you’re using a keyboard or DAW virtual instrument as your sound source, try to find a plain-sounding solo trumpet with a strong attack and a steady sustain. You may have to scroll past dozens of weedy orchestral brass presets to find it, but hopefully there’ll be a trumpet in there with the right energy, attitude and attack.

In addition to offering a selection of solo trumpets, today’s keyboard workstations usually contain trumpet section patches of two or more players. For the purposes of sketching an arrangement, it’s OK to use such a patch, providing the instruments within it are played in unison (ie. all trumpets play the same note). You should avoid ‘pop horns’ presets which feature a mix of different instruments, and never use patches with built-in octaves, as these become horribly muddy when you build up chords and harmony lines. If you’re not sure whether you’re hearing octaves, A/B the preset in question with a solo trumpet patch and listen carefully for traces of a lower note underneath the main pitch. I would also discourage the use of patches and samples with built-in chords, as they will stick out like a sore thumb and prevent you from dreaming up your own chord voicings!

The alternative to working with a keyboard or DAW instrument is to use a sample library, some examples of which I’ve listed in a box elsewhere in this article. While sampled instruments have the potential to sound more realistic and professional than a synth patch, they require more user effort. The first hurdle is navigating endless lists of patches to find a simple, playable solo trumpet: pop brass sample libraries invariably offer a choice of sustained notes and short staccato deliveries, as well as other styles with mysterious names like ‘fall’, ‘shake’ or ‘doit’, which I’ll explain in a future article. To get started, a straight solo trumpet sustains patch will do nicely.

Examples 1 to 5. Don’t be fooled by the simplicity of these single- and double-note ‘baps’ — they can be very effective.While I’m on the subject of sample-based instruments, here’s a useful tip: when working with samples, you can strengthen note attacks by layering a staccato or marcato patch over a sustains patch. Set the staccato and sustains patches to the same MIDI channel and experiment with their relative volumes to get the ideal blend. (The trick doesn’t always work, but with luck you’ll end up with an all-purpose combi which you can use for both short and long notes.)

Examples 1 to 5. Don’t be fooled by the simplicity of these single- and double-note ‘baps’ — they can be very effective.While I’m on the subject of sample-based instruments, here’s a useful tip: when working with samples, you can strengthen note attacks by layering a staccato or marcato patch over a sustains patch. Set the staccato and sustains patches to the same MIDI channel and experiment with their relative volumes to get the ideal blend. (The trick doesn’t always work, but with luck you’ll end up with an all-purpose combi which you can use for both short and long notes.)

Punctuation

If you listen to some of the classic ’60s arrangements listed in the aforementioned box, you’ll notice that the brass players don’t actually play that much — having started the song with a strong melodic statement, they often recede into the background and don’t re-emerge till the middle instrumental break. When they do play, the parts are often sparse and simple, leaving plenty of space for the vocal. Wayne Jackson of The Memphis Horns (a trumpet and sax duo who wrote and performed the brass parts on many of the records in our list) summed up the philosophy thus: “Don’t step on the singer.”

Wise words. Thankfully, you can avoid this by keeping your brass arrangement nice and simple in the passages where the vocalist is doing his or her thing: wait till the vocal line finishes (say, at the end of a chorus), then throw in a loud, staccato single-note accent — bap! Congratulations — you just created your first brass arrangement.

Examples 6 to 7. Repeated-note phrases such as these will grab the listener’s attention.Other examples of this single-note rhythmic punctuation are shown in examples two to five. You can place the simple double-hits accents shown in examples two and three more or less anywhere in the bar, while four and five are also good all-purpose rhythm licks. As well as being the perfect way of adding a musical ‘exclamation mark’ to the end of a vocal line, such accented interjections are concise enough to throw in behind a vocal without undue risk of upstaging the singer. However, if you want the brass to make a more attention-grabbing rhythmic statement, either of the repeated-note phrases in examples six and seven would make a great, dramatic way of ending a passage.

Examples 6 to 7. Repeated-note phrases such as these will grab the listener’s attention.Other examples of this single-note rhythmic punctuation are shown in examples two to five. You can place the simple double-hits accents shown in examples two and three more or less anywhere in the bar, while four and five are also good all-purpose rhythm licks. As well as being the perfect way of adding a musical ‘exclamation mark’ to the end of a vocal line, such accented interjections are concise enough to throw in behind a vocal without undue risk of upstaging the singer. However, if you want the brass to make a more attention-grabbing rhythmic statement, either of the repeated-note phrases in examples six and seven would make a great, dramatic way of ending a passage.

Short Melodic Phrases

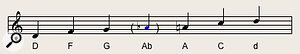

Examples 8 to 12. Five short melodic riffs, the last two featuring a held note at the end.We can extend this idea by introducing some melodic movement into our rhythmic phrases: examples eight to 12 show five examples of short melodic phrases, the last two of which introduce a held note at the end of the riff. For these examples I’ve used the D-minor white-note scale of D, E, F, G, A, B and C (example 13); for a tougher, more austere effect, you can omit the E and B and use the D-minor pentatonic blues scale of D, F, G, A and C (example 14). If you wish, you can add the extremely bluesy note of A flat, traditionally used as a passing note to the adjacent pitches of A or G.

Examples 8 to 12. Five short melodic riffs, the last two featuring a held note at the end.We can extend this idea by introducing some melodic movement into our rhythmic phrases: examples eight to 12 show five examples of short melodic phrases, the last two of which introduce a held note at the end of the riff. For these examples I’ve used the D-minor white-note scale of D, E, F, G, A, B and C (example 13); for a tougher, more austere effect, you can omit the E and B and use the D-minor pentatonic blues scale of D, F, G, A and C (example 14). If you wish, you can add the extremely bluesy note of A flat, traditionally used as a passing note to the adjacent pitches of A or G.

Simple blues licks sound good on pop brass, a reminder of where the underlying musical style came from — in fact, the blues scale is such a familiar sound in this context, you can even throw in the odd minor-key blues lick over a major chord without it sounding wrong!

You’ll notice in these examples that there are often spaces between the notes, and that some phrases terminate before the end of the bar. These spaces and rests are important: they define the rhythmic shape of phrases, make space for other instruments and help emphasise the contrast between long and short notes that is such a vital feature of brass writing. When creating an arrangement, you should pay as much attention to where you end notes as to where you start them, as this has a significant impact on overall feel. Example 13. D-minor white-note scale.

Example 13. D-minor white-note scale. Example 14. D-minor pentatonic blues scale.

Example 14. D-minor pentatonic blues scale.

Strong Melodic Statements

At some point in an arrangement, the horns should step into the spotlight and cut loose — otherwise, what’s the point of having them? The great records of the soul era were bossed by memorable brass melodies. As Wayne Jackson put it: “Maybe within the song, the horns will get to make a statement so strong as to be unforgettable.” That was certainly the case with ‘Knock On Wood’, ‘In The Midnight Hour’ and ‘Hold On I’m Comin’’, all of which feature rousing, irresistibly catchy horn intros and middle eights.

![]() Example 15. The D-major pentatonic scale of D, E, F#, A and B has a happy, homely and proclamatory sound.If you want to turn the clock back and write a brass break so stunningly melodic that people will be queuing up to sample it for the next 50 years, you should follow the golden rule and keep it simple. As the old cliché goes, less is more — rather than throwing in every note under the sun, you could restrict yourself to the D-major pentatonic scale of D, E, F#, A and B (example 15), which has a happy, homely and proclamatory sound. Examples 16 and 17 are examples of strong melodic phrases created with this simple five-note major scale.

Example 15. The D-major pentatonic scale of D, E, F#, A and B has a happy, homely and proclamatory sound.If you want to turn the clock back and write a brass break so stunningly melodic that people will be queuing up to sample it for the next 50 years, you should follow the golden rule and keep it simple. As the old cliché goes, less is more — rather than throwing in every note under the sun, you could restrict yourself to the D-major pentatonic scale of D, E, F#, A and B (example 15), which has a happy, homely and proclamatory sound. Examples 16 and 17 are examples of strong melodic phrases created with this simple five-note major scale.

Examples 16 and 17. These strong melodic phrases were created with the simple D-major pentatonic five-note major scale (see example 15).Choosing the right scale for your melodies obviously depends on the chords used in the music, but since many tunes featuring pop horns are based on simple, homogenous chord sequences, it’s possible to write melodies that stay on the same major or minor scale throughout. This has parallels in the rock world, where guitarists often repeat the same lick over a set of chord changes (with, it has to be said, occasionally painful results).

Examples 16 and 17. These strong melodic phrases were created with the simple D-major pentatonic five-note major scale (see example 15).Choosing the right scale for your melodies obviously depends on the chords used in the music, but since many tunes featuring pop horns are based on simple, homogenous chord sequences, it’s possible to write melodies that stay on the same major or minor scale throughout. This has parallels in the rock world, where guitarists often repeat the same lick over a set of chord changes (with, it has to be said, occasionally painful results).

The aforementioned song ‘One Way Glass’ is a good case in point: over a chord sequence of (let’s say) D, C, G and D, the brass line sticks to a six-note major scale of D, E, F#, G, A and B (no seventh is used). The glorious, largely pentatonic tune that emerges thus owes its success not to a blizzard of jazzy notes, but to a strong, focused and deliberately simple melodic statement with a great, catchy rhythm.

Adding A Lower Part

Example 18. While the trumpet top line alternates between a minor and major third, the tenor sax below moves between a sixth and a flattened seventh.As mentioned earlier, many bands feature a horn section of trumpet and tenor sax. Despite its size, this economic line-up can make a big sound, and that sound is easy to achieve: we simply double the trumpet part with a tenor sax playing an octave lower. Being a physically larger, lower-pitched instrument, the tenor sax would struggle to play a melody up in the trumpet’s high register, but bringing its part down an octave works a treat, adding beef, rasp, honk (and, for quieter passages, a breathy, velvety timbre) to the trumpet’s pure, clarion tone. The playing ranges of the trumpet and tenor saxophone are shown below.

Example 18. While the trumpet top line alternates between a minor and major third, the tenor sax below moves between a sixth and a flattened seventh.As mentioned earlier, many bands feature a horn section of trumpet and tenor sax. Despite its size, this economic line-up can make a big sound, and that sound is easy to achieve: we simply double the trumpet part with a tenor sax playing an octave lower. Being a physically larger, lower-pitched instrument, the tenor sax would struggle to play a melody up in the trumpet’s high register, but bringing its part down an octave works a treat, adding beef, rasp, honk (and, for quieter passages, a breathy, velvety timbre) to the trumpet’s pure, clarion tone. The playing ranges of the trumpet and tenor saxophone are shown below.

In addition to beefing up the trumpet part, the tenor sax can add simple harmonies under a top line. I’ll expand on this topic in next month’s article, but for now I’ll leave you with the funky lick in example 18 — this quirky motif (which I always associate with James Brown) is based on a flattened fifth (aka ‘tritone’) interval which rapidly oscillates up and down a semitone. In this particular case (written in the key of A), the trumpet top line alternates between a minor and major third (C & C#), while the tenor sax below moves between a sixth and a flattened seventh (F# & G). You can invert the intervals so that the sixth and seventh play the top line with the thirds placed underneath, as shown in example 19.

Scary Quant

Example 19. The intervals in example 18 can be inverted, so that the sixth and seventh play the top line with the thirds placed underneath.When sequencing your brass parts I urge you not to use quantisation (the automatic fixing of notes to an exact timing grid). While it’s fine for programmed drums, percussion, bass lines and some rhythmic keyboard or synth parts to be quantised, other elements in the track need to maintain their natural human timing, otherwise the whole thing will end up sounding mechanical and computerised.

Example 19. The intervals in example 18 can be inverted, so that the sixth and seventh play the top line with the thirds placed underneath.When sequencing your brass parts I urge you not to use quantisation (the automatic fixing of notes to an exact timing grid). While it’s fine for programmed drums, percussion, bass lines and some rhythmic keyboard or synth parts to be quantised, other elements in the track need to maintain their natural human timing, otherwise the whole thing will end up sounding mechanical and computerised.

A downside to this naturalistic approach is that obvious timing errors inevitably occur from time to time. The way to deal with this is to use your sequencer’s note editor to locate the offending notes and drag them back or forwards in time, using small movements, until they feel right with the track. Don’t be fooled into thinking that an event that lands exactly on the beat must be ‘right’ — quite often, a slightly late entry helps create a relaxed feel, and notes played slightly before the beat can add urgency and excitement. The secret here (if it can be called that) is not to rely on your eyes, but to use your ears.

If you’re adjusting the timing of a chord, it’s good practice to preserve the relative position of its component notes by highlighting them all and moving them as a unit — that way, you’ll preserve the microscopic timing differences between pitches that occur naturally in a played chord. This may seem academic or nit-picking, but subtle micro-timing issues of this kind have a cumulative effect on the overall rhythmic feel.

Assembling The Elements

To illustrate how the various accented interjections, rhythmic phrases and melody lines outlined above can be combined into a coherent whole, I created the brass arrangement shown in example 20 — it’s in the key of D, uses a tempo of 115bpm and is based on a simple 12-bar sequence, like the chorus of Duffy’s 2008 single ‘Mercy’ (and before that, countless blues tunes stretching back to the dawn of time).

Example 20. This retro-flavoured 12-bar brass arrangement in the key of D shows how accented interjections, rhythmic phrases and melody lines can be combined into a coherent whole. A trumpet plays the top line, with tenor sax doubling the trumpet part an octave lower (except for the chords in bars 6, 9, 10 and 12, where the sax plays the lower harmonies).I’ve deliberately gone for a retro feel in this arrangement to demonstrate how classic soul licks can be strung together. A contemporary arrangement would probably focus more on syncopated rhythmic figures at the expense of the melodic material — this stylistic shift reflects the evolution of sixties soul into the more 16th-note based, 1970s funk styles that persist to the present day. This mini-composition works well with trumpet playing the top line and tenor sax doubling the same part an octave lower (except for the chords in bars six, nine, 10 and 12, where the sax plays the lower harmonies).

Example 20. This retro-flavoured 12-bar brass arrangement in the key of D shows how accented interjections, rhythmic phrases and melody lines can be combined into a coherent whole. A trumpet plays the top line, with tenor sax doubling the trumpet part an octave lower (except for the chords in bars 6, 9, 10 and 12, where the sax plays the lower harmonies).I’ve deliberately gone for a retro feel in this arrangement to demonstrate how classic soul licks can be strung together. A contemporary arrangement would probably focus more on syncopated rhythmic figures at the expense of the melodic material — this stylistic shift reflects the evolution of sixties soul into the more 16th-note based, 1970s funk styles that persist to the present day. This mini-composition works well with trumpet playing the top line and tenor sax doubling the same part an octave lower (except for the chords in bars six, nine, 10 and 12, where the sax plays the lower harmonies).

I’ve written in the chord changes where they occur — note that although these chords are nominally major, the brass line frequently features a minor third (F), which creates some harmonic tension and a nice bluesy feel. The arrangement starts out in time-honoured fashion with a strong melodic statement — hopefully you’ll also recognise some of the other musical ideas outlined above in there!

Retro Versus New

It may seem contradictory that I stress the need for original, creative musical thought while simultaneously banging on about brass styles dating back half a century, but please bear with me — as I said at the start of the article, rather than being forgotten artifacts long ago swept away by the tides of time, the historic musical precepts of pop brass live on in modern arrangements, sound as cool as ever, and maintain a vital link with the past which it would be foolish to ignore.

Please also understand that this article is intended as a primer: in the same way that you’d learn a handful of chords and some basic scales on an instrument and jam on a 12-bar blues before launching into a complicated jazz chart, the simple musical examples above are intended as starting points from which you can hopefully go on to build your own arrangements. Put another way, you have to learn to walk before you can run, and I hope this helps to provide a modicum of upright forward motion!

Next month I’ll introduce the lower brass instruments, investigate the wonderful world of funk, talk about how to construct chords for bigger brass line-ups, take a look at the role of keyswitches in brass sample libraries and examine ways of adding expression and realism to synth brass patches and sampled brass instruments. I’ll also give some tips on how guitar players, bassists, keyboard players and drummers can adapt their parts in order to integrate successfully with a horn section in a band setting.

Instrument Ranges

Although synth patches and samples don’t have to replicate the limitations of real-life instruments, it helps to have a working knowledge of their playable pitch ranges — and, of course, if you’re hiring real players, knowing their instruments’ ranges is essential! Below are the playing ranges of a Bb trumpet and tenor saxophone, often heard playing together in brass arrangements. Middle C (C4) is marked in blue. (Trumpets are made in a variety of models that play in different keys: although the trumpet in C crops up in orchestral scores, the model ubiquitous in pop and jazz circles is the trumpet in Bb.)

Although synth patches and samples don’t have to replicate the limitations of real-life instruments, it helps to have a working knowledge of their playable pitch ranges — and, of course, if you’re hiring real players, knowing their instruments’ ranges is essential! Below are the playing ranges of a Bb trumpet and tenor saxophone, often heard playing together in brass arrangements. Middle C (C4) is marked in blue. (Trumpets are made in a variety of models that play in different keys: although the trumpet in C crops up in orchestral scores, the model ubiquitous in pop and jazz circles is the trumpet in Bb.)

These ranges are not hard limits: good players can produce higher and lower notes but, generally speaking, the extreme high and low end of instruments’ registers tend to sound strained, with a resulting diminution of musical quality and usefulness.

Brass In Your DAW

When looking for ‘pop’ brass sounds to use in your DAW, try to steer clear of orchestral libraries. Although some contain playing styles that can work in a pop context, their deliveries generally lack the gutsy, uninhibited attitude required for pop, and their instrumentation and articulation menus are likely to contain significant omissions. Below are some of the better brass libraries and instruments that feature keyswitchable playing styles optimised for pop, soul, R&B, funk and jazz big band. They’ve all been well received by the sampling community, and with intelligent programming will add realism and colour to your horn charts. (SOS reviews in brackets).

Sample Instruments

- Chris Hein Horns Vols. 1-4

- Big Fish Audio First Call Horns (http://sosm.ag/big-fish-firstcall-horns)

- Big Fish Audio Vintage Horns

- Fable Sounds Broadway Big Band (http://sosm.ag/fablesounds-broadway)

- Vir2 Instruments Mojo Horn Section (http://sosm.ag/vir2-mojo-horns)

- Native Instruments Session Horns (http://sosm.ag/ni-session-horns)

Modelled Instruments

Sample Modelling offer an impressive range of solo instruments, including Trumpet, Trombone and various saxophones (http://sosm.ag/sample-modelling-trumpet and http://sosm.ag/sample-modelling-solo-wind-brass).

Phrase Libaries

I’m not a great advocate of pre-recorded phrases, but recommend the Memphis Horns sample library (http://sosm.ag/memphis-horns), created by Wayne Jackson (trumpet) and Andrew Love (tenor sax). Recorded by the guys who defined the style, this comprehensive lexicon of soul brass licks has the advantage of total authenticity, and it’s also a great educational resource.

20 Classic Brass Arrangements

Here’s a ‘top 20’ of records dating back to the mid-1960s that feature iconic brass arrangements. Often dreamed up on the spot by the players at the recording session, these deceptively simple, but highly catchy, horn parts defined a musical template that persists to the present day. These tracks are recommended listening for all would-be brass arrangers, and for fans of the golden age of soul!

1. ‘Dancing In The Street’ (Martha & The Vandellas) 1964

2. ‘Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag’ (James Brown) 1965

3. ‘In The Midnight Hour’ (Wilson Pickett) 1965

4. ‘I Can’t Turn You Loose’ (Otis Redding) 1965

5. ‘I Got You (I Feel Good)’ (James Brown) 1965

6. ‘Rescue Me’ (Fontella Bass) 1965

7. ‘Uptight (Everything’s Alright)’ (Stevie Wonder) 1965

8. ‘Hold On I’m Comin’’ (Sam & Dave) 1966

9. ‘Land Of 1000 Dances’ (Wilson Pickett) 1966

10. ‘Knock On Wood’ (Eddie Floyd) 1966

11. ‘Road Runner’ (Junior Walker & the All Stars) 1966

12 ‘Mustang Sally’ (Wilson Pickett) 1966

13. ‘Respect’ (Aretha Franklin) 1967

14. ‘Soul Man’ (Sam & Dave) 1967

15. ‘Tell Mama’ (Etta James) 1967

16. ‘Dance To The Music’ (Sly & the Family Stone) 1967

17. ‘Hard to Handle’ (Otis Redding) 1968

18. ‘It’s Your Thing’ (The Isley Brothers) 1969

19. ‘Vehicle’ (The Ides Of March) 1970

20. ‘Move On Up’ (Curtis Mayfield) 1970

If you can find it online, check out the rampaging version of ‘I Can’t Turn You Loose’ on the 1966 UK TV show ‘Ready Steady Go’!

Article Overview

Part 1: This four-part series explains all you need to know about creating brass arrangements for a range of genres.

Part 2: The second in our four-part series deconstructs funk licks, discusses the implications of using live players and explains how to get more expression and feel into your sampled brass arrangements.

Part 3: A simple, catchy tune with a funky rhythm may be all you need to create a highly commercial horn hook — but harmony is also an essential ingredient in brass arrangements.

Part 4: We conclude our series with an overview of arrangement techniques and a peep into the world of big-band brass.