Combining the guts of an 02R mixer with a fully featured multitrack recorder, the AW4416 ended up being a prodigiously complex beast. Our hands-on workshop shows you which of those snazzy features work best in practice, and how to use them efficiently.

Arguably the biggest product release of 1996 was the Yamaha 02R digital mixer, featured on the cover of SOS in February of that year. The product offered pro-quality automated mixing with motorised faders, two onboard effects processors, plus EQ and dynamics on all channels; and all for the sum of £7049! In those days, that seemed like an unbeatable batch of features for such a modest price, despite the fact that the various I/O boards and accessories bumped the overall figure rather higher. Still, the industry marches on, and just over four and a half years later, the guts of the mixer had been bundled together with a hard disk recorder, sampler, and CD-RW drive to create the considerably less expensive AW4416.

The more basic AW2816, and AW16G were released at a later date, each one improving on the integration of mixer and recorder, and therefore becoming more user-friendly. By their standards, the AW4416 is a little daunting, but it offers a great deal of functionality to anyone willing to spend the time getting to grips with it.

This short series won't attempt exhaustively to describe all the workstation's features in detail — the two manuals do a fine job in that department already. What I'll be doing is giving practical examples of how all these features can be used and abused to best effect during recording and mixing.

Setting Levels For Mixing

Each of the AW's mixer channels has an attenuator, and these become very handy when preparing for a mix, because they allow each fader to be used over its optimum range. If you look closely at the faders you will see that they offer the most control around the 0dB position. For example, moving the fader about a centimetre from the 0dB position will cut or boost a signal by around 5dB, whereas when the fader is at the bottom of its travel, the same movement represents a 40dB change! As a result, mixing is easier and more accurate when the fader movements are made near to the 0dB mark.

When you come to mixdown, any fader set far below its unity gain position makes mixing less accurate, because the resolution of the AW4416's faders gets coarser at lower gain settings — you can tell this from the scale printed to the side of each fader.

When you come to mixdown, any fader set far below its unity gain position makes mixing less accurate, because the resolution of the AW4416's faders gets coarser at lower gain settings — you can tell this from the scale printed to the side of each fader.

Unless all your sources happen to be at the correct volume straight away, the chances are that after you've found the right mix balance some faders will be up at +6dB while others may be hovering down at -40dB. By adjusting the attenuators on each channel, all the faders can be set at a 0dB (unity gain) starting point.

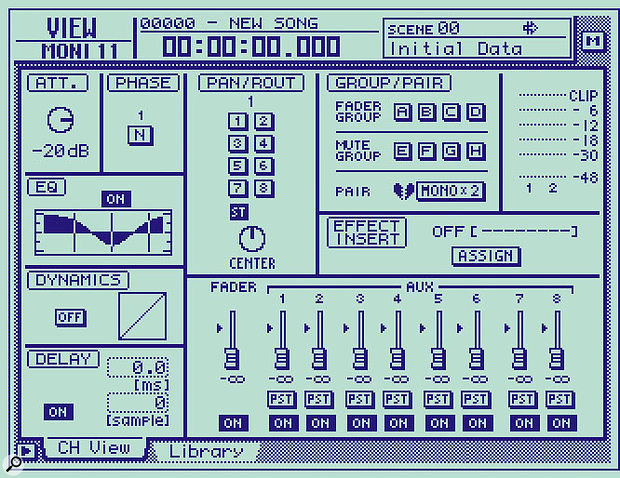

To bring the fader back to roughly unit gain while retaining your mix balance, first press the Ch View button and use the cursor keys to navigate to the channel's attenuation control.

To bring the fader back to roughly unit gain while retaining your mix balance, first press the Ch View button and use the cursor keys to navigate to the channel's attenuation control.

To do this, start with the track which is mixed the loudest, and is fundamental to the mix — often the lead vocal. If the track fader is at +4dB, then pull it down to its unity-gain position, and then use the channel attenuators to bring all the other channels down by the same amount. The quickest way to apply the change to all the tracks is by pressing the Ch View button to bring up the channel pages and then using the Sel buttons in each fader layer to select each track or pair of tracks in turn, pulling down the attenuator for each one as you go. Once this has been done, the previous mix balance will be regained, but most of the faders will still not be at unity gain.

In this example, channel 11's fader is about 20dB too low, so the Att control should be adjusted to its -20dB setting...

In this example, channel 11's fader is about 20dB too low, so the Att control should be adjusted to its -20dB setting...

Any faders that are above 0dB should be taken down to unity gain, and their channel attenuators increased by the same amount to retain the mix balance. For example, a guitar track which is still faded 2dB up can be taken down by that amount, and then have its attenuator increased by 2dB. Conversely, any faders below 0dB gain need to be pushed up — if a fader is moved from -10dB to 0dB then the attenuator can be lowered by 10dB. The fader can now be raised back to its highest-resolution position.

The fader can now be raised back to its highest-resolution position.

Once this process has been competed for all tracks, the basic mix should sound the same as before, but all the faders will be in a line at 0dB. When it's time to create an automix, you will be able to boost and cut from this position. If you find that one of the tracks needs more boost in places, just attenuate everything else down a few decibels more to gain the extra headroom. This only takes a few seconds to do, and it retains the relative balance.

Alternatively, consider using the channel dynamics processor to dial in a few decibels of gain. The disadvantage of using the channel attenuators is that they come before the dynamics processor, so any pre-existing compressor threshold settings will require re-evaluation. Adjusting the output of the dynamics processor avoids the problem; however, it also means that if you later decide to bypass a redundant compressor, for example, then the balance will immediately change. More food for thought is that the dynamics processors allow up to 18dB of gain to be added, whereas the attenuators do not go above 0dB and therefore reduce the chances of overloading the output.

If the overall balance is correct, but clipping is occurring on the main Stereo buss, press the Ch View button and the Stereo track selection button. Here you will find the attenuator for the stereo buss, as well as EQ and dynamics processing, allowing the signal to be brought under control.

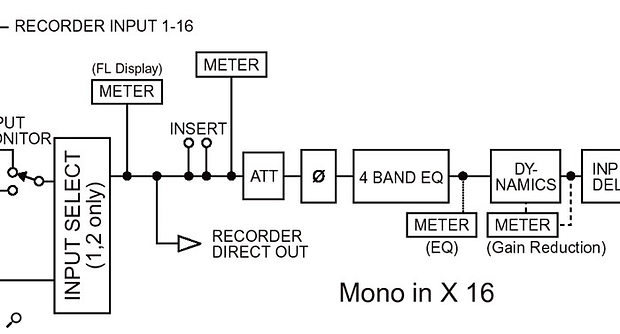

As you can see from this block diagram of the AW4416's mixer (shown in full at the back of one of the two manuals), the one disadvantage of using the channel Att controls to bring channel faders into their area of greatest control resolution is that this may interfere with any dynamics processing already set up. In such cases, the make-up gain control in the relevant dynamics section can be used instead, as long as you don't bypass it at any later stage.

As you can see from this block diagram of the AW4416's mixer (shown in full at the back of one of the two manuals), the one disadvantage of using the channel Att controls to bring channel faders into their area of greatest control resolution is that this may interfere with any dynamics processing already set up. In such cases, the make-up gain control in the relevant dynamics section can be used instead, as long as you don't bypass it at any later stage.

Managing Scenes During Mixdown

I've come to the conclusion that the most efficient way to automate a mix is to start by laying down a series of Scenes, positioning them at key places throughout a Song, and identifying their positions with markers. Each Scene can be used to determine the basic mix palate for the block of audio it precedes, and it creates a foundation from which smaller changes can be made using the dynamic automation.

Of course, a whole Song can be automated without the use of Scenes, but Scenes are a much neater way of working because they act like chapters in a book, insomuch as they break everything down into manageable lumps. It is also quicker to apply mix changes to Scenes than it is to work through and edit masses of dynamic automation bit by bit.

I like to set up a Scene which is relevant to the largest portion of the Song and then work from there, rather than starting at the beginning and creating a new Scene for each section as it is encountered. For each section I load the core Scene, alter it appropriately, and then re-save it with a different name.

It's a good idea to test your basic Scene mix on a variety of systems before creating numerous edited copies, so that they don't all need to be changed if some drastic alterations to the overall setup are required. If, however, you've already set up your Scenes and find that you need to change the same settings across several, you can cut down on the work by saving edits into the various EQ, dynamics, and effects libraries. For example, if the EQ on a stereo drum track needs changing for all of a Song's Scenes, first make the changes for the main Scene and save the new setting into the EQ library. When editing the rest of the Scenes, rather than making all the same changes by hand, just recall the saved setup from the library for the drum part, and then re-save the Scene. Once a series of carefully programmed Scenes is in place, a Song actually requires very few real-time automation moves before it's complete.

Fine-tuning Dynamic Automation

When it comes to mixing, there are often occasions when a small block of audio, possibly just a note or two, gets in the way and needs to be removed. Perhaps the timing is out, or the notes are just not right. In some circumstances in may be possible to edit out the offending notes, or simply mute them. However, the sudden absence of a track of audio can sound unnatural. In such cases a fader move is a more appropriate solution, as it effectively allows the mix engineer to bury the unwanted notes. Ducking just a note or two is usually difficult to get right by hand, but the automation allows a fader move to be tuned almost to perfection.

To tackle the scenario outlined above, solo the offending audio and find the start of the first duff note. Write down its exact location, using the Waveform display to help if necessary. Then do the same for the end of the last bum note. Next, defeat the solo, so that the whole composition is heard, and rewind to just before the beginning of the section. Set the Automix facility to record fader data, make sure that the Fader Edit Out mode is set to Return, and start the track playing. At the start of the duff section, briefly duck the fader and stop recording — at this stage it doesn't matter if the fader move starts at the right spot or goes to the right level.

Make your way to the Automix Event List page (the F4 tab in the main Automix screen) and find the fader data you have just recorded. Using the cursor keys and data wheel, change the time of the first move to the start time you noted down, and alter the last event to the end time. You will notice that the smallest timing increment is 25 milliseconds, so data positioning is not as accurate as editing, but that still means that there are 40 steps to every second, so you can get things more or less right. The next step is to reposition the rest of the fader increments between the two outside points. To keep things smooth, it's probably best to have the volume drop rapidly in small steps to its benign level, and then rise back up in the same fashion. The actual fade amount can then be tweaked until the notes are suitably unnoticeable.

Such methods are time-consuming, but worth considering when a small and accurate patch-up job is needed. The same basic principles can also be applied to other automation data, like pan positioning, or the placement of Scenes.

Using The Waves Y56K Card With Scenes

I am among those AW users who have invested in the Waves Y56K mini-YGDAI card (see the Wave Hello box for more information on this product). This card offers eight mono effect chains (any pair of which can be linked for stereo operation) each with as many as five effects blocks into which the various processors can be loaded. The effects chains can be inserted into the path of any relevant monitor channel, or they can be fed from a spare aux send buss and returned via any vacant input channels. The former routing is most useful for the various compressor, limiter, de-esser, and EQ effects, while the latter suits the reverb and delay algorithms. The Y56K's dynamics processors and equalisers all greatly improve on the in-built equivalents provided as standard by the AW4416's mixer.

Clearly, eight channels of processing offers a lot of flexibility, but I soon found myself wanting to swap effects setups around during a Song by using Scenes with different Y56K chain setups. Unfortunately this is not practically viable, because you get significant drop-outs when recalling Scenes with drastically different Y56K chains — the card has to reload its whole internal DSP setup. For this reason, I plan my basic mix with the relevant channel insert and send settings for the eight Waves channels, and then make sure they remain the same throughout a mix. If needs be, I avoid changing Waves chains by editing audio so that it physically moves to a track with a particular insert effect at the point where a Scene change happens. That said, it is possible to change, say, an EQ setting or compressor level within a Y56K effects algorithm under Scene control without causing the card to reload its whole DSP setup. Another option, of course, if you think you're going to run out of effects horsepower, is to bounce audio to disk through the Waves processor, keeping the unprocessed audio safe on a spare virtual track.

Wave Hello

The Y56K mini-YGDAI card offers some of the company's most sought-after processors and effects for use in both mixing and mastering situations. I'd certainly recommend it to any committed AW4416 users who feel frustrated with the in-built dynamics, EQ, or delay/reverb effects that come as standard.

The board does take up a slot that could otherwise be occupied by a mini-YGDAI I/O board, although the Y56K does include eight channels of ADAT lightpipe I/O. It's also important to note that the Y56K has some compatibility conflicts with other optional I/O boards. Firstly, it cannot be used when the AW4416's other mini-YGDAI slot has either of the Apogee converter boards installed — this risks damaging the multitracker. A similar risk of damage prevents the simultaneous use of a second Y56K. In fact only the MY4AD, MY8AD, and MY4DA can be used alongside the Y56K.

If you own the Waves Y56K board, you can now download three new plug-ins from www.y96k.com, although you'll need to update your card's operating system to run them.

If you own the Waves Y56K board, you can now download three new plug-ins from www.y96k.com, although you'll need to update your card's operating system to run them.

The standard Y56K tools are the L1 Limiter, L1 Ultramaximizer, Renaissance EQ, De-esser, Renaissance Compressor, Multitap Delay, and Trueverb reverb. Current owners may also be interested to learn that there are now three more Waves products available for download and installation on a standard Y56K card: the Renaissance Bass, Renaissance Vox, and L2 Ultramaximizer. The first of the three generates harmonic sub-bass frequencies and is best suited to dance-music applications. The Renaissance Vox is an easy-to-use compressor and gate combination specifically designed for use on vocals, and the L2 Ultramaximizer is an alternative to the L1 Ultramaximizer. All three processors can be bought together as the Waves Power Bundle, and can be downloaded into the Y56K via a computer.

Before any new updates can be made, however, the Y56K Maintenance Update OS has to be installed. The software is also available in download format from the same site. Whether or not you desire the three extra Waves products, the update may well be worth installing anyway, as it is free and is said to increase stability and crash recovery in case of power failures. The installer uses the Y56K's RS232 connector for performing the update, so a standard RS232 nine-pin serial cable and a PC with a COM port are needed. Unfortunately the installers are available only for Windows machines.

Saving Space: Editing & Optimising

If you are recording your Songs at 24-bit resolution then you will almost certainly find that a four-minute composition using all 16 tracks creates a file that is hundreds of megabytes in size. If there are additional virtual tracks too, then it's possible to get a project of a gigabyte or more. Obviously, big files take up a lot of hard disk space, but they also become problematic when attempting to make backups. For example most CD-Rs and CD-RWs offer about 700MB storage, so a 1GB Song requires two recordable CDs and increases backup time considerably.

Taking dead space out of your audio tracks has the most immediate advantage that it makes it much easier to navigate through your recordings — the solid black bars in the track view above give no visual cues to your arrangement, whereas the edited tracks here make the song layout obvious at a glance. The other advantage of such topping and tailing is that you can then use the Optimise routine to reclaim disk space and also to reduce the size of the project prior to backing up.

Taking dead space out of your audio tracks has the most immediate advantage that it makes it much easier to navigate through your recordings — the solid black bars in the track view above give no visual cues to your arrangement, whereas the edited tracks here make the song layout obvious at a glance. The other advantage of such topping and tailing is that you can then use the Optimise routine to reclaim disk space and also to reduce the size of the project prior to backing up.

To help matters, the AW4416 has an Optimise feature (press the Song key and then the F3 tab to find it) which allows unwanted data to be discarded, thus reducing file sizes significantly. If you are re-recording a track over and over, you will notice that the file size goes up rapidly as the AW stores each take ready for undo requests. The Optimise function does away with all undo layers in one go, although it retains virtual tracks and all mix data, so it certainly pays to check that a series of edits are successful before optimising.

Song sizes can also be kept to a minimum by trimming each track using the digital editing options. A 24-bit recording of silence uses just as much memory as a 24-bit full orchestral recording, so erasing areas of recorded inactivity is advisable. If several seconds are taken from both ends of all 16 tracks and their virtual tracks, it's possible to claw back several minutes of 24-bit recording, thus reducing file size by hundreds of megabytes. Remember, though, that the file-saving benefits of editing will only be noticeable after optimisation.

Curiously, erasing audio from within a track, rather than from the start and end, does not seem to reduce file size, and for some reason the activity often has the effect of increasing it by several megabytes! Of course it's not totally necessary to edit the gaps between vocal lines or guitar breaks, because you can automate channel muting, and many people will do just that to save time.

Nevertheless, erasing silences is thoroughly worth doing because it dramatically improves the visual landscape of the Track View page, making navigation through a track far easier — it becomes possible to tell where you are in a Song just from glancing at the display.

Effective Track Naming

You can name tracks and virtual tracks using either a connected mouse or the cursor keys and Enter button. Although the track name can be up to 16 digits long, it's unwise to have long track names, because the all-important Track View screen only displays the first eight of these (including spaces). Long names are simply truncated, so naming a track Elec Gtr Lead, and another Elec Gtr Rhythm will, for example, read Elec Gtr for both tracks, which is rather unhelpful!

You can name tracks and virtual tracks using either a connected mouse or the cursor keys and Enter button. Although the track name can be up to 16 digits long, it's unwise to have long track names, because the all-important Track View screen only displays the first eight of these (including spaces). Long names are simply truncated, so naming a track Elec Gtr Lead, and another Elec Gtr Rhythm will, for example, read Elec Gtr for both tracks, which is rather unhelpful!

As you can see, a naming strategy needs to be employed to ensure that the important information is contained in the first eight digits. I tend to abbreviate names as much as possible, sometimes using product codes when I know that certain sounds have been used from a particular sound module. User settings for EQ, dynamics, and effects can also be named using 16 digits, but as these are only ever viewed in the relevant library lists where all 16 digits are visible, it's unnecessary to abbreviate them.

The Value Of Defragmentation

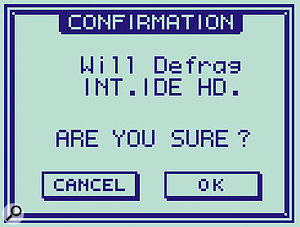

In the AW4416's v1.3 OS update, a disk defragmentation facility was added to combat the operational problems the AW4416 suffers when the disk becomes fragmented. Given that there are so many ways you can edit and re-record data, it doesn't take long before the information relating to a particular Song is scattered far and wide across the hard drive, and this means that the recorder has to work hard to reassemble it in real time on playback.

To get to the defragmentation option you must press the File button and then the F3 key to recall the Disk Utility screen. The data wheel must then be used to select 'Int.IDE', which is the name of the internal drive, whereupon you are given a choice of either Defrag or Format options. The manual small print advises that defragmentation requires approximately one hour per gigabyte of disk space, which is a little worrying if you have a large hard disk installed! However, I have found that even after months of use the whole process takes something approaching a couple of hours rather than several days. Nevertheless, if you do have an uninterruptible power supply then it might be worth running your recorder from it while defragmentation is in progress, as a power cut during defragmentation could corrupt the drive.

As crashing is an occasional hazard, it pays to back up at the end of every session. I ike to use CD-RW disks for this purpose until I am satisfied that a recording is finished, at which point I make a slightly more permanent backup to CD-R.

Archiving Songs

Although only one Song can be loaded at any time, you can transfer individual tracks from one Song to another. There are many reasons why this could be a useful procedure, one of which is Song archiving. For example, if a Song is being developed over a long period of time it's quite possible that all the virtual tracks could be used up, or at least a project could become confusingly cluttered with tracks and virtual tracks in various states of development. This may also result in a project becoming so large that it has to be saved onto several disks.

One solution is to save the Song with a new name, so that two versions of the same thing exist. Name one as the archive and one as the working project. Go through the current version and delete anything which is not immediately required, freeing up as much space as possible. Work can then continue on the project, but if a previous bit of audio is required, it can be imported into the current project from the archived version. Both versions can, of course, be backed up separately.

Multitrack Mastery

That's all for now, but there's still plenty more to be said about the AW4416, so tune in again next month for the concluding instalment of tips next month, where I'll be covering some methods for making creative use of the effects and signal generator in Part 2.

Automatic Muting

If you try to record and play back too many tracks simultaneously, the AW4416 will automatically mute some of the playback tracks so that it can cope with the recording duties. If you don't like its choice of muting, then you can change it from the main Track View screen.The AW4416 has to juggle its resources on occasion, particularly when it is attempting to play back and record at the same time. In 24-bit mode, for example, it often has to mute some playback tracks if too many other tracks are already playing back.

If you try to record and play back too many tracks simultaneously, the AW4416 will automatically mute some of the playback tracks so that it can cope with the recording duties. If you don't like its choice of muting, then you can change it from the main Track View screen.The AW4416 has to juggle its resources on occasion, particularly when it is attempting to play back and record at the same time. In 24-bit mode, for example, it often has to mute some playback tracks if too many other tracks are already playing back.

If you're using the Quick Rec 2 page to route the audio for recording, this causes the tracks to mute automatically, but the tracks that are muted are often ones you actually need to hear when performing your overdub, so some user intervention can be required.

In the track view screen, the arrow keys allow any track to be highlighted and its mutes to be turned on or off. However, to change a mute when a track is armed for recording you will first need to mute an alternative track. At this point, a non-vital track can be muted leaving the important one available for playback.

Software Updates & Manual Supplements

Since it starred on the cover of SOS's 15th birthday Issue in November 2000, the AW4416 has had its software revised on a number of occasions. The machine is no longer in production (I am told that this is because one of the key components sourced from a third-party manufacturer has been discontinued), so it is unlikely that the current version 2.12 OS will now be superseded, even though there are users who still continue to write computer utilities for the product.

Since it starred on the cover of SOS's 15th birthday Issue in November 2000, the AW4416 has had its software revised on a number of occasions. The machine is no longer in production (I am told that this is because one of the key components sourced from a third-party manufacturer has been discontinued), so it is unlikely that the current version 2.12 OS will now be superseded, even though there are users who still continue to write computer utilities for the product.

If you have just bought a second-hand machine, or have one which has an old version of the software, you should be aware that there were many minor updates that happened between versions one and two, rendering the original manuals rather outdated in many areas. Therefore it's worth getting hold of the manual supplements for versions 1.2/1.3 and 2.0 if you don't already have them — these are available for download from www.aw4416.com/e/download/download.html. The last OS update can also be obtained from the same site (www.aw4416.com/e/download/ver_up2.html), but no new features were added since version 2.0, beyond the ability to work with a further six CD-RW drives.