It's been possible to make music on Apple laptops for many years now, but creating a working mobile system is harder than it looks. Fortunately, one SOS contributor has years of experience to pass on...

Ever since my student days, whatever I've been doing always seems to have involved a lot of travelling. As a result, I have always found it difficult to make music from a home studio; whenever I've set one up, I've found myself leaving on a three-month trip the following day or week. Not surprisingly, I've been interested in portable recording systems for years, and have been attempting to use laptop computers for recording since long before they were really powerful enough, or possessed of the necessary interfaces to make it possible. But it's been worth the effort — once you do get a portable music setup together, it is a wonderful thing. It means that pretty much whenever and wherever inspiration strikes, you can be nailing the idea down into a working demo, before the all-too-capricious muse deserts you. How many times have you had a musical idea, struggled to get all your music gear switched on and working, only to find when it's all finally up and running that you can no longer remember your original idea? This used to happen to me all the time, but now I just open up my Mac laptop to wake it from Sleep mode and I'm ready to work (I rarely fully Shut Down any portable Mac that I am using for this reason).

A Trip Through History

However, using Apple laptops for music wasn't always this straightforward. Following my earliest experiences with portable computers (detailed in the 'Early Days' box below), the first Mac to come along which allowed the same sort of flexibility as my 8500 Power Mac home rig was the G3 Powerbook codenamed 'Wall Street', in early 1999. The introduction of the so-called Altivec 'velocity engine' had occasioned a serious leap in power which was perfect for running Cubase VST, and I had just started to become aware of the developing software synths and samplers which would run on computer CPUs. Bitheadz's Retro AS1 was the first synth I saw, and their Unity was the first sampler (and all before Steinberg had come up with the idea of VST Instruments). Having ascertained that the Wall Street was powerful enough to play back a reasonable number of tracks of samples and synth sounds, I treated myself to one of these at the 1999 MacWorld in San Franscisco. With both Unity and Retro installed on my Powerbook, I could seriously make music anywhere for the first time.

But the best thing about the Wall Street for me was that the stereo mini-jack audio input on the side would take the signal from my Zoom guitar processor and allow me to record electric guitar into Cubase VST. With a small master keyboard and a one-in, one-out Apple Desktop Buss-based (ADB) MIDI interface from Opcode, I had a mobile music rig which would fit into the knapsack I had bought for the Wall Street. So with my guitar over one shoulder and the Powerbook on the other (with an octave of MIDI keyboard poking out the top), I was ready to venture anywhere and make music. It did give me a bit of a lopsided walk (which a friend of mine dubbed 'the Wall Street Shuffle') but it did get me on the move musically.

The next logical stage was to try to get rid of the Zoom, with its insatiable appetite for batteries. The first VST plug-in effects stayed away from this area, concentrating mainly on things like chorus, reverb, and compression, but I knew that it was only a matter of time before someone started doing decent guitar effects as VST plug-ins. Line 6 had had the TDM version of Amp Farm for some time of course, but that was no use, as it needed a bucketload of Digidesign hardware to run. It took about six months before VST guitar effects processing finally made it onto my laptop in the form of Stomp'n'FX from DSound in the Czech Republic. These were brilliant little DSP effects designed especially for guitarists, and took their on-screen appearance from Boss's stomp-boxes, which they emulated. Also, the Czech PCs and Macs on which they were created were seriously underpowered, which meant they were coded very economically — I found that I could chain two or three effects together and obtain an excellent processed guitar sound which hardly took any of the Wall Street's DSP power. Now all the DSP was being done inside the computer, and I could dispense with the Zoom processor. I still have this Wall Street-based system and it works perfectly, as long as you don't use too many Retro AS1 synth sounds or DSP plug-ins.

I remember producer Duncan Bridgeman coming into my London office fresh from working on a track on Dido's first record to check out my Wall Street mobile system before he headed off around the world with Jamie Catto of Faithless on the project which was to become 1 Giant Leap. If ever there was a validation of the idea of the mobile Mac music system, it is that project, for which Duncan carried a portable Mac-based studio on the pair's round-the-globe journey, capturing music and situations which couldn't have been recorded any other way — a giant leap for mobile music on computers indeed (for the full story, see SOS February 2003, or read it at: www.soundonsound.com/sos/feb03/articles/1giantleap.asp).

First Steps — From Tandys To Early Macs

I first became aware what a portable computer could do for you in the mid-'80s, when I was able to write articles for the US music-technology mag I worked for on a Tandy portable next to a swimming pool in Marina Del Rey, California. It was most enjoyable, and I remember wishing at the time that I could do something similar for music. The Atari I used for music-making back then was deskbound, not so much because of the computer itself but because all of all the musical equipment you needed to use with it. Several friends of mine used the Stacy (Atari's luggable) but for me there was no appeal in this because you couldn't carry all the MIDI devices which you needed for music around with you. I do remember programmer Will Mowat biking between his home in Kilburn and the Soul II Soul studio in Camden with a Stacy in his bag, but then he had all the gear he needed to attach at both ends of his journey. Unless you could do this, there seemed little point in being able to move the computer about, because back then it didn't make or record any of the sound.

By the early '90s, I was writing on a Mac 850c with a colour screen and enough power and memory to run Passport's Alchemy and Steinberg's (as it was then) Recycle, which allowed me to create and edit drum loops. On one occasion, I was even able to complete some important loop editing on a plane to Japan. Sample editing was always the strength of the Mac, ever since the first Sound Designer packages, but it took a long time for me to be convinced to start MIDI sequencing on one. The Atari always seemed better for this, and they developed the built-in audio side of things more quickly than Apple, allowing companies like Steinberg to start recording audio alongside MIDI much earlier. The unexpanded Atari Falcon was doing eight and then 16 channels of audio (thanks to Cubase Audio 16) with DSP effects long before you could do anything worthwhile on an unexpanded Mac, and back then, portable computers could not be expanded to improve their audio capabilities.

Once the Power PC chips came along in the mid-'90s, making DSP processing available inside Macs, and Steinberg unveiled the entirely host-based Cubase VST, I finally capitulated and started making music on the Mac, and this soon became my main sequencer (the Falcon had served me well for a while, but track counts on the Mac were now exceeding the hardware limit of eight linear or 16 compressed tracks on the Falcon). Running this on a desktop Power Mac 8500 with Korg's 1212 I/O card, I had a great home system. The trouble was, with my itinerant lifestyle, I was rarely at home to enjoy the benefits of the setup, and when I was, I had no energy left from travelling to dive in and make music. So I started looking for a mobile Mac which would let me do at least the stereo recording on the move. And that was where my G3 Wall Street Powerbook came in, as related in the main part of this article.

PCMCIA As A Fidelity Solution

My Wall Street system was perfect when recording at the quality of the Apple audio input (it was fine for guitar which I was then going to put through an overdrive effect anyway), but clearly for higher fidelity and mic-level recordings something else was needed. Duncan of 1 Giant Leap was making vocal recordings, of course, and he needed something better too. The solution he found was also the next product I tried to work with: Digigram's VXPocket PCMCIA card, which was then the only possible third-party audio I/O solution for Mac laptops, and gave you high-quality stereo in and output. It worked fine for Duncan on his trip, but I found it nigh-on impossible to use for multitracking because of the high latency (even with its ASIO driver, the latency was higher than that of the Mac OS). I'm still not sure how Duncan managed to make his work, though I believe that more recent versions of this PCMCIA card have managed to reduce the latency significantly.

I decided that the best thing to do was to stick with a PCI I/O card I knew and trusted, like the Korg 1212 I/O or Sonorus STUDI/O, but find a way to make it work on portables, which of course had no PCI slots. My next trip to San Fransisco for MacWorld brought me in contact with the company Magma and their PCI expansion chassis, and I decided to check into the suitability of this for running my system with higher-fidelity and multi-channel I/O. Their CB2S chassis held two PCI cards (and an extra SCSI hard drive if you wanted it) and connected to the portable via my Wall Street's PCMCIA connector. Lo and behold, my Sonorus STUDI/O card worked first time, and I was soon running a system which allowed me to connect 16 channels digitally to and from my Korg 168RC digital desk via the STUDI/O's dual ADAT optical ports, just like my desktop system at home.

However, this was somewhat stretching the definition of a portable system — the Magma chassis had a significantly bigger footprint than the Wall Street, and weighed twice as much, even before you put any cards or drives in it. Worse, it needed mains power. I found that it was transportable for use at trade shows, but otherwise I kept it at home as a sort of audio docking station for the Powerbook, as only Arnold Schwarzenegger would regard the entire rig as portable. For the sort of work I was doing on the road, the basic Wall Street was fine, and then I would just plug the PCMCIA card in when I got back to base and be able to record 16-channel audio.

However, this was somewhat stretching the definition of a portable system — the Magma chassis had a significantly bigger footprint than the Wall Street, and weighed twice as much, even before you put any cards or drives in it. Worse, it needed mains power. I found that it was transportable for use at trade shows, but otherwise I kept it at home as a sort of audio docking station for the Powerbook, as only Arnold Schwarzenegger would regard the entire rig as portable. For the sort of work I was doing on the road, the basic Wall Street was fine, and then I would just plug the PCMCIA card in when I got back to base and be able to record 16-channel audio.

A Change Of Direction

Then, just as Apple were about to corner the market in minimalist mobile music rigs, they decided to undermine their unassailable position by doing three things simultaneously. Firstly, they decided to drop ADB from their laptops — the Apple Desktop Buss by means of which all the then-current MIDI interfaces on the Mac worked. They put USB on instead, which promised eventually to give access to higher-quality audio I/O as well as MIDI I/O, but of course, when the first Powerbook came out with this change in 2000 (codenamed Pismo), there were no shipping USB MIDI interfaces, let alone USB audio interfaces. Although the USB MIDI interfaces arrived fairly swiftly, it was quite a while before anyone delivered a reliable USB audio solution. I remember several articles written for Sound On Sound in this period where I had to warn people to see the interface working on their Powerbook before buying it.

Eventually, the solutions arrived from the likes of Midiman (now M Audio), Swissonic and Tascam. For several years, I used Swissonic's USB Studio (which had excellent mic preamps and phantom power) in conjunction with a new 500MHz Titanium laptop to record vocals in my co-writer Simone's living room. The first-generation Titanium lacked a built-in audio input altgether (another Apple revision too far; the input was restored on later-generation Titaniums), so a USB device was vital. The USB Studio worked so well on demos, we often struggled to get a better vocal sound and performance in a fully fledged studio, because Simone was so relaxed recording at home.

By this time, the palette of software synths I was using was expanding rapidly to include Native Instruments' brilliant B4 and their superb Battery for drums, Emagic's EXS24 sampler and EVP88 for strings and electric pianos and an increasing number of synths like Steinberg's Wave 2.x, NI's Absynth and GMedia's M-Tron. As a result, I was putting increasing pressure on my Wall Street's CPU — one reason I eventually moved up to the Titanium laptop. In the interim, I performed more and more frequent bounces to audio, which reduced the CPU load. This was time-consuming, though, and a further interruption to the creative process. Since last year, Emagic's Logic has offered a better solution with its Freeze function, which carries out a similar bounce-to-audio process for the contents of tracks, whether they contain MIDI-triggered soft synths or audio parts with lots of CPU-hungry plug-ins. Freeze is much faster than bouncing, however, and better still, you have the option to 'Unfreeze' if you decide you do want to change the tracks you've bounced down in this way. Most other sequencers have now introduced similar functions too.

Hammerfall Goes PCMCIA

For some time, I had been using an RME Hammerfall in the Magma chassis at home. It was the natural successor to my Korg 1212 and Sonorus STUDI/O as it featured three ADAT I/Os instead of the Korg's one or the Sonorus' two, making 24-channel digital I/O possible. What I really wanted was to have this available for my laptop, so I pestered RME regularly about it, telling them that if only they could come up with a PCMCIA version, they would have the perfect solution for portables. When they finally did in the form of the Hammerfall DSP system, they had really thought it through. There was a PCMCIA and a PCI version of the card so that you could use it on either your portable or desktop machine, and there were a couple of interface choices: the Digiface, which gave you 24 channels of digital I/O, and the Multiface, with eight-channel analogue I/O. They were kind enough to get me one of the very first PCMCIA systems (as I had pushed the idea so hard at them) and I have been using it very successfully ever since. It is particularly good as a mobile PCMCIA solution, as it features a MIDI In and Out as well. I'm unaware of any other PCI or PCMCIA card which performs as well as the Hammerfall DSP system in terms of latency and sheer amount of audio I/O. It's particularly well integrated with Steinberg's Cubase and Nuendo, too; Steinberg even rebadge and resell the Hammerfall DSP as a dedicated interface for Nuendo, the Audiolink (pictured below). It also works well with Logic.

Firewire & mLAN

By the time the third series of G3 Powerbooks came out (codenamed Pismo), they had Firewire instead of SCSI, and everyone began to seriously consider this as the best way to expand the audio capabilities of portable computers. Mark Of The Unicorn were first to market with their 828 Firewire box and this proved to be a most elegant and reliable solution to multi-channel I/O. However, I always felt that the Firewire-based mLAN system had more potential, as it could allow all kinds of Firewire-equipped devices to talk to each other (MOTU's products, though Firewire-based, used a proprietary protocol).

RME's PCMCIA card-based Hammerfall DSP recording system, shown here with its breakout box in its Steinberg Audiolink livery (it is also available from RME under their name).However, although Yamaha were the original instigators of mLAN, it's taken a long time to be able to use their products with it in a sensible way. They released a YGDAI mLAN card for their digital desks a couple of years ago, but the YGDAI format restricts audio I/O to a maximum of eight audio channels, so although mLAN is capable of much more, you still needed three YGDAI cards to handle 24-channel I/O, and most people then couldn't see the advantage over ADAT optical connections. This situation has now changed with the arrival of Yamaha's fully mLAN-compatible 01X (see review in last month's SOS), and the fact that mLAN is supported in the latest versions of Mac OS X. I hoped to show off mLAN's integration with Mac OS X at last year's Sounds Expo show in a demo I did with producer Steve Levine, but the update to OS 10.2.4, the revision that made Mac OS fully mLAN-compatible, was not released until the day after the show closed, so all of the interfacing in our demo had to be done via ADAT optical connections. Because of this lousy timing, very few people are aware even now that OS X's Core Audio fully supports the mLAN standard, and has done since February 2003! Hopefully the arrival of more mLAN-compatible products will help to change this.

RME's PCMCIA card-based Hammerfall DSP recording system, shown here with its breakout box in its Steinberg Audiolink livery (it is also available from RME under their name).However, although Yamaha were the original instigators of mLAN, it's taken a long time to be able to use their products with it in a sensible way. They released a YGDAI mLAN card for their digital desks a couple of years ago, but the YGDAI format restricts audio I/O to a maximum of eight audio channels, so although mLAN is capable of much more, you still needed three YGDAI cards to handle 24-channel I/O, and most people then couldn't see the advantage over ADAT optical connections. This situation has now changed with the arrival of Yamaha's fully mLAN-compatible 01X (see review in last month's SOS), and the fact that mLAN is supported in the latest versions of Mac OS X. I hoped to show off mLAN's integration with Mac OS X at last year's Sounds Expo show in a demo I did with producer Steve Levine, but the update to OS 10.2.4, the revision that made Mac OS fully mLAN-compatible, was not released until the day after the show closed, so all of the interfacing in our demo had to be done via ADAT optical connections. Because of this lousy timing, very few people are aware even now that OS X's Core Audio fully supports the mLAN standard, and has done since February 2003! Hopefully the arrival of more mLAN-compatible products will help to change this.

The recent 2004 Winter NAMM show saw many more manufacturers announcing Firewire interfaces, but M Audio beat them to market with their Firewire 410, announced last year (and also reviewed in last month's SOS). I tried to use one of these in my demos for this year's recent Sounds Expo show, and M Audio kindly supplied me with one, but I was unable to get it working before the show. Just as this article was ready to go to press, the problem was traced to the power supply, and M Audio swapped the unit for another one, whereupon I was able to complete a successful two-hour recording session with it. This story underlines a useful piece of advice when it comes to trying out interfaces for laptops before you buy them — given that the computer you'll be using with the interface is portable, why not take it to the shop and try it out there? That way, you can check your chosen interface works, not only on the shop's system, but on the computer you'll be using it with. You may well find that the shop staff are more motivated to help you test the device in the store if you do all of this before you actually part with any money... !

OS X & Class Compliance

The moment when I first realised just how good Mac OS X was going to be for musicians was in January 2002, when Evolution sent me an MK249C controller keyboard the night before a series of OS X Roadshows that I did in London. I had spent all day failing to get OS X working with music applications — Celemony's Melodyne, the only OS X-compatible application shipping at the time, was the only thing that had worked reliably all day — and was about to give up and do my entire presentation in OS 9 when the MK249C turned up. I plugged it in via USB and to my amazement, Core Audio (then in its infancy in Mac OS 10.1) immediately recognised it and offered it as an available Core Audio device in Ableton Live. I was then able to trigger loops in Live and also Reason. Together with Melodyne, I suddenly had a coherent demo of OS X's Core Audio and its advantages for musicians — and the highlight was seeing the MK249C plugged in and registering on the computer with no drivers installed.

The MK249C was the first so-called class-compliant USB device I'd seen, and Evolution went on to produce many more, such as the UC33 controller, the faders of which were excellent for controlling the drawbars on NI's B4 or Emagic's EVB3. Class compliance can work with Firewire devices as well, and now that Evolution has been absorbed into the M Audio empire, I hope that M Audio's controllers and interfaces will benefit from this advance too.

Banishing Latency

The other key feature of Core Audio for musicians is the ability to set your latency level without needing ASIO or some other third-party driver to make this available to you. Typically within Logic I have the buffer set to 256 samples which gives a latency of just under 6ms at 44.1kHz. This is fine for triggering software synths via MIDI, but you have to remember that if you are monitoring recordings through the program so you can put effects on them, you have to double this figure to account for the latency at both input and output. Consequently, if you are processing instruments as you record them and need to hear the processed signal, you might need to reduce the sample buffer to 128, even though this places a greater load on your Mac's CPU. One of my favourite programs, RT Player (the shell application for the DSound guitar plug-ins I mentioned earlier) defaults automatically to a buffer size of 64 samples, presumably because of the legendary intolerance for latency on the part of guitar players. This means there is just under three milliseconds of latency at 44.1kHz, accounting for both input and output, and I have not noticed this over-burdening my CPU.

Of course, if you are using an older machine, you will have to make greater allowance for the burden which these short buffer settings place upon your processor. You can either do this by running fewer software synths and effects or putting up with longer latencies! Many of the USB devices on the market now allow you to monitor at source (also known as zero-latency or through monitoring), which means you can get around the problem in recording completely, as long as you don't want to monitor effects on the input signal while recording. Of course software synths and samplers cannot be monitored at source as they originate inside the computer, although you only have the output signal to worry about, so latency is half that experienced when monitoring recordings through input and output stages.

My Current Portable System

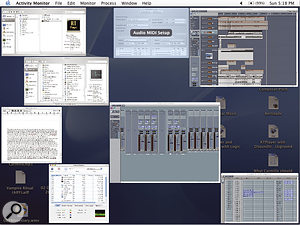

Making use of Panther's new Exposé function to deal efficiently with multiple open application windows. Who needs multiple monitors when you can do this?To explain my current renewed enthusiasm for mobile computing, let's have a look at what I am currently using for music composition, demo recording and live performance. I recently purchased a 12-inch Powerbook, the first portable I have used which, for me, really improves on the Wall Street I purchased six years ago — the machine is just so compact, and the 1GHz processor performs extremely well. My main sequencer these days is Emagic's Logic Platinum together with the EXS24 sampler and all Emagic's software synths, as well as my favourite Native Instruments plug-ins, which I've now got working in Logic as Audio Units plug-ins. On the controller side, I use the Evolution MK249C to control my latest favourite plug-in, GMedia's impOSCar, and of course RT Player provides processing for my guitar. I use the mini-jack out of the Powerbook to output from the computer most of the time. I find that the quality is pretty good as long as you don't crank the output up to full; back it off a couple of notches and the sound is clean enough to put through an average PA when gigging. If I do need higher fidelity or to record via mic preamps with phantom power, then I still dig out my class-compliant Swissonic USB Studio. Whenever I need to output from the laptop in surround, I use the two-in, six-out Emagic EMI 2|6 (recently renamed the A26, which sounds more like a road to a South-coast resort to me, but there you go).

Making use of Panther's new Exposé function to deal efficiently with multiple open application windows. Who needs multiple monitors when you can do this?To explain my current renewed enthusiasm for mobile computing, let's have a look at what I am currently using for music composition, demo recording and live performance. I recently purchased a 12-inch Powerbook, the first portable I have used which, for me, really improves on the Wall Street I purchased six years ago — the machine is just so compact, and the 1GHz processor performs extremely well. My main sequencer these days is Emagic's Logic Platinum together with the EXS24 sampler and all Emagic's software synths, as well as my favourite Native Instruments plug-ins, which I've now got working in Logic as Audio Units plug-ins. On the controller side, I use the Evolution MK249C to control my latest favourite plug-in, GMedia's impOSCar, and of course RT Player provides processing for my guitar. I use the mini-jack out of the Powerbook to output from the computer most of the time. I find that the quality is pretty good as long as you don't crank the output up to full; back it off a couple of notches and the sound is clean enough to put through an average PA when gigging. If I do need higher fidelity or to record via mic preamps with phantom power, then I still dig out my class-compliant Swissonic USB Studio. Whenever I need to output from the laptop in surround, I use the two-in, six-out Emagic EMI 2|6 (recently renamed the A26, which sounds more like a road to a South-coast resort to me, but there you go).

I am genuinely blown away with how much power is available in this tiny little portable. One of the songs Simone and I are currently performing live uses a Logic song triggering drums and strings from EXS24, synth bass from impOSCar, and synth strings from Emagic's own ES2 synth — and I still have enough CPU power to run a four-effect guitar multi-effects patch from RT Player for the live electric guitar solo.

Laptop Troubleshooting

Of course, you do need to make sure that all the power the CPU offers is being used by your music applications. More than any other type of computer, laptops have lots of extra facilities to facilitate their mobile use which suck a lot of power out of the CPU. The golden rule is to have nothing switched on except what you actually need for your performance. So turn Airport off, disable Bluetooth, switch Ethernet off and make sure Appletalk is disabled until you next need to do your email. Otherwise, you may find your computer is scanning for a non-existant 802-11 LAN (Airport in Applespeak) and using enough power for two plug-ins to do so, or preventing your samples playing back properly in case someone wants to send you a file via Bluetooth.

A further word of warning to all would-be music lecturers and demonstrators: when you plug in the connector which allows your screen to be duplicated on a projector so your audience can see what you are doing, the connection sucks a serious amount of power out of the computer. As a result, a song which plays back perfectly at home may crash mid-playback. A similar thing can happen if you decide to use an additional monitor with your Powerbook, even if it is only mirroring what is showing on your built-in screen. In general I prefer to manage without, and Mac OS X's Exposé function can go a long way to making this possible (see screenshot above). By using the new Activity Monitor in Panther (as mentioned in last month's Apple Notes), you can check on the overall CPU usage. Of course, sequencers like Logic have their own Performance Meters, but these will only show the DSP load for which the sequencer is responsible — it won't tell you what other open apps are doing. Activity Monitor can really help you to pin down unexplained CPU loads.

Conclusion

I have been genuinely amazed since getting this 1GHz G4 Powerbook how much is now possible on a portable — the days of struggling to achieve a minimum of usability while others sensibly eschewed laptops in favour of static, but more powerful setups seem behind us at last. Of course, desktop systems are still faster, but you could always invest in a dual-processor G5 for your home studio to provide extra tracking and mixdown muscle when you come to polish off productions started on your laptop — funds permitting, of course! But despite the continued difference in spec, if you think about it, a 1GHz G4 CPU was the top of the desktop Power Mac range just 18 months ago, so you are able to do now what was possible in a desk-bound machine just 18 months ago. If you have any interest in mobile Mac-based recording and sequencing, there's never been a better time than now!