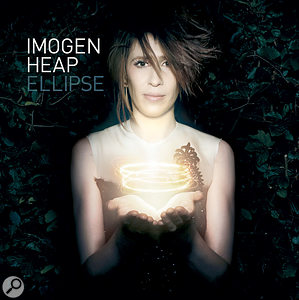

Imogen Heap travelled the world to write songs for her new album — and recorded it in her childhood playroom, with the help of some unusual toys!

Imogen Heap is right on the verge of becoming a household name. Even if you haven't encountered her, you've almost certainly heard her music in movies like Garden State and Chronicles of Narnia, and TV shows like Heroes, Six Feet Under and The OC. It's also hard to miss Imogen if you're a follower of the Web 2.0 revolution, where she seems to have defined the way in which artists connect with fans on‑line via Twitter conversations and YouTube video diaries.

Imogen released a solo album, the anagrammatically titled iMegaphone, in 1998, before forming a collaboration with producer and songwriter Guy Sigsworth under the moniker Frou Frou. The pair released the critically acclaimed album Details in 2002. Imogen's next album, Speak For Yourself (2005), was self‑written, self‑recorded, self‑produced, and self‑mixed, not to mention independently released.

Round Trip

Toys in the playroom: many of Imogen Heap's sounds begin life as samples from toys and other household objects.

Toys in the playroom: many of Imogen Heap's sounds begin life as samples from toys and other household objects.

In 2007, following a hectic couple of years that saw tours, Grammy nominations and a major‑label re‑release of Speak For Yourself, Heap found herself back in London considering her next steps. "I knew I had to do something, but my head really wasn't there, and all my gear was in tatters from touring; and there was loads of stuff I had to do at the house because I'd been away for so long — I just didn't want to be there. I hadn't been on holiday for such a long time — like five years — so I spun Google Earth around a few times, and thought, 'I just want to be somewhere that's the furthest away from anywhere else on the planet'.”

The result was a three‑month writing trip starting in Hawaii and stopping off in Australia, Japan, China, Fiji and Thailand. The trip saw a return to a more traditional approach to songwriting, separate from studio production: "I did take some bits [of gear] with me, just to record the ideas, but not with the thought that I'd use any of it on the record. I wanted to get the songs written, because with the last record I wrote the album and produced it in tandem, and found myself in situations where I'd have a track pretty much done, then I'd have to crowbar in this melody and lyric over the top and end up stripping it all away anyway. So I thought, 'I've learned my lesson, I'll go and write the songs old‑school style with the piano, and get them sounding good on their own.'”

Being away from the studio also freed up more space for lyric writing. "I hate writing lyrics when I could be making sounds, but I thought 'If I'm not with all my gear, I'll just have to write the lyrics,' and I really enjoyed it then.”

In the end, half the songs on the album were written on the trip, and the other half were written in England while her new studio was being built. The exception is 'The Fire', which includes both recordings of an improvised piano piece in Maui and a family bonfire back in England.

Home Studio

Imogen Heap's studio is centred around a Digidesign D‑Control Pro Tools controller.

Imogen Heap's studio is centred around a Digidesign D‑Control Pro Tools controller.

Speak For Yourself had been produced in a rented studio space at the Atomic Studios complex in South London, in a room previously occupied by Dizzee Rascal. However, for the next album, Imogen really wanted to set up a place of her own. "I wanted to create a space with a sound that I could control, because it's so noisy everywhere. But to do that in London is, like, millions of pounds.”

Before her trip, Imogen's father had suggested that she consider her childhood home: a unique, grand, oval‑shaped house, tucked away in a leafy corner of the London/Essex borders. Although a move back to the house where she grew up seemed a backwards step at first, Imogen didn't want to let the house go out of the family, and as her travels progressed, the idea of building a studio in her old playroom began to appeal. Far from being a dark underground space, the basement area that was to become the studio is surrounded by a passageway (the 'runaround'), and has windows to the open air.

"I thought it would be wonderful to be down here,” reacalls Imogen, now sitting in the finished studio. "Immediately I thought of the playroom: it's downstairs but there's still light. It actually has some natural soundproofing because of this wall of air.”

The main control room area occupies half the basement, so is semi‑circular. Mastering engineer Simon Heyworth recommended that acoustic masters WSDG come and assess the space to help transform the playroom into a pro mixing environment. "It wasn't as bad as I thought it was going to be, although when I said I wanted a fireplace they said 'Ooh, you can't!' And actually there is a bit of an issue that it does give us more bass, but I just live with it.”

The ceiling was lowered to reduce the reverb time in the room, and the walls were treated with two four‑inch layers of Rockwool separated by a gap. Wood panelling was initially chosen for the final acoustic treatment, mainly to avoid a lengthy wait for plaster to dry, but they subsequently found a new quick‑drying plaster which encroached less into the space than the panels. After the shell was complete, Imogen worked with a carpenter to furnish the room, with their designs being vetted in WSDG's modelling software.

Heaps Of Gear

This fixed rack houses the input chain used for non‑vocal sources, and includes a Focusrite Liquid 4Pre preamp, Line 6 PodXT guitar processor, Korg rackmounted guitar tuner, TC‑Helicon Voiceworks Plus vocal processor and Joemeek VC1 input channel and SC2.2 compressor.

This fixed rack houses the input chain used for non‑vocal sources, and includes a Focusrite Liquid 4Pre preamp, Line 6 PodXT guitar processor, Korg rackmounted guitar tuner, TC‑Helicon Voiceworks Plus vocal processor and Joemeek VC1 input channel and SC2.2 compressor.

The core equipment for the studio changed little from the modest kit‑list used on the previous album. "It's the same monitors — the MKs — which actually almost died, they're a bit buzzy around the mid frequencies, but it was in the last month of mixing and I didn't want to change them.”

The main new purchases were a Focusrite Liquid4Pre, which handles most mic recording other than vocals, and a Digidesign D‑Control work surface for Pro Tools. Despite the fact that she mixes entirely 'in the box' in Pro Tools, Imogen admits ruefully that she probably doesn't use half the features on the desk beyond the faders, keyboard, and monitoring section. "I bought it thinking that it would help me get out from here [the centre section] and I'd be really dynamic with it, but in reality I just sit here. But it looks great, and when people come they go 'Wow! It looks like a real studio!'”

There are two outboard racks, both dedicated to input and recording duties. One is Imogen's flightcased signal path for vocal recording, and the other is used for recording all other sources. The permanent rack houses the Liquid4Pre, a Line 6 Pod for guitars, a TC Helicon Voiceworks Plus and some Joemeek rack processors. The flight case is dominated by an Avalon VT737 tube channel, but also has an Electrix Repeater and another Voiceworks.

Remote Recording

Imogen Heap's portable vocal recording chain, headed up by an Avalon VT737 input channel and also featuring an Electrix Repeater delay and a second TC‑Helicon Voiceworks Plus.

Imogen Heap's portable vocal recording chain, headed up by an Avalon VT737 input channel and also featuring an Electrix Repeater delay and a second TC‑Helicon Voiceworks Plus.

Imogen's vocals on Ellipse were recorded through the Avalon, using a Neumann TLM103. The original plan was to set up a vocal booth area and use Apple's Remote Desktop software on a MacBook Pro to control recording in Pro Tools. However, the fan noise from the laptop was too intrusive. In the end, all the vocals were recorded in the control room, with the mic shielded by an SE Electronics Reflexion Filter. Although the Remote Desktop scheme proved unsuitable for vocals, it did get used elsewhere. "I did get it working, and I used it upstairs in the dining room because I've got tie‑lines from the piano to down here, and from the hall.”

As well as the Steinway piano upstairs, a drum kit was set up in a separate room behind the main studio. Other acoustic instruments were generally recorded in a fold‑away booth made of baffles to one side of the control room.

Imogen's recording technique is more intuitive than textbook, an approach she admits stems from laziness and impatience. "I'm really bad!” she confesses, when discussing recording the drum kit. "I usually have two overheads, and I might have one on the snare. Then I'll have one ambient mic, perhaps in the 'runaround' — because you get some great natural reverb in there — and I just compress the hell out of it. Or I'll have a mic in another room, or a cupboard to get another sense of space. But I don't have 10 mics and spend ages choosing. I'm so impatient, I just want to get in and play it. And if a channel's not working, I'll just think 'To hell with it, I'll just have one mic!'”

In fact, she thinks that her "lackadaisical engineering process” is partly responsible for the character of the sounds she makes, and she relishes the creative challenge of dealing with them in Pro Tools. She does occasionally worry about what guest musicians visiting her studio will think, though. "I do get a slight sweat on! But I just do it really quickly by ear. After a while you get a feel for space and distance, and if you understand the body of an instrument and where the sound feels best coming out of — it's mostly instinctive. I do sometimes get nervous that someone might think, 'You don't mic my cello up like that!', but thankfully I don't work with musicians like that!”

Foundation Sounds

Even after numerous bounce‑downs, the expansive 'Tidal' Session was a huge challenge to arrange.

Even after numerous bounce‑downs, the expansive 'Tidal' Session was a huge challenge to arrange.

Many of the sounds on Ellipse come from Imogen's collection of unusual instruments and sound toys, or everyday objects processed into something new. In particular, she decided to use sounds from around the house as starting points, partly because of the poetic sense in which the house was linked to the album, but mainly as a practical framework or limitation to focus her efforts.

"Most of the sounds on the record do begin as unlikely candidates. You can easily get lost and spend hours even beginning a starting point in Logic, because you have so many options open to you. It's easy to get lost in something like [Native Instruments'] Massive, listening to all the fun sounds. So I generally start with something acoustic.”

The song '2‑1', a dark, brooding epic that was originally destined for the second Narnia film, is a good example. The opening pad is a pitched-down 'whirly': one of those corrugated plastic pipes that you spin around your head. This is followed by some deep timpani‑like thumps that underlie the rhythm throughout the track. These turn out to be the large plastic light panels in the studio ceiling being tapped with a finger — a sound stumbled upon while trying to flick out an unfortunate fly that had expired inside the light fitting.

Evolving Process

Delving further into the production process of '2‑1' reveals a surprising approach. "I did all the vocals first, all the harmonies, and actually got most of the [fader] rides done before I did anything else. I know it sounds weird, but I want to make sure that when you hear the voice you never lose it, and it always works on its own.”

The chord structure was fleshed out with piano, before the basic rhythm was added with the light panels. Next came strings, arranged in Logic. Most of the strings on the album started off sample‑based, using either Ultimate Sound Bank's Plugsound Pro or East West's Symphonic Orchestra Gold. "I know what sounds good with them, but I knew that I'd end up with a live cellist and violinist on it to give the impression that there's more live strings. And when anything sounds slightly 'keyboardy', I bring up the real ones and take down the other ones, or EQ out whatever sounds synthesized.”

The final basic ingredient was a triple‑layered organ sound riffing around the chords in the verses. This completed the kernel from which the song could then be developed in Pro Tools. "I knew that I wanted it to go off into this dark, angular space, but I didn't know what that would entail yet.”

One of the first elements to be added was another of those unlikely sources: a jaw harp. After several rounds of processing and mangling, the jaw harp provides a dark, growling pulse at some points, and a bouncing rhythm in the choruses that pushes and pulls against a sub‑bass component. "It's going through a massive long reverb in [Waves'] TrueVerb, and then volume‑ridden and processed and reversed... and probably going through TrueVerb again! I love how you can have this little tiny sound that turns into a monster after a couple of hours of playing.”

Numerous additional elements were then woven into the song, including brushed drums, trumpet, harp, and probably a few things that have been forgotten. Despite the large array of components layered into the Pro Tools Sessions, the arrangements and mixes were kept spacious and open by limiting the number of things happening at once. This occasionally involved some painful decision‑making, most notably in the case of the track 'Tidal'. The 'Tidal' Session grew to dozens of tracks, including Indian vocals, synth lines, acoustic and electric guitars, 8‑bit Gameboy‑style sounds, and plenty more besides. "It had a ridiculous amount of tracks, I just could not decide where to go. It had so many elements that I loved, and I was trying to make them all work.”

In the end, she decided to let the song follow a rollercoaster ride through all the different directions that the production had taken. "It's a total mish‑mash of about five different approaches to the song! I was nervous that it would be self‑indulgent, but it seems to be the one people are really liking.”

Elliptical Mixing

Everything on Ellipse was mixed by Imogen at her studio. Early in her career, Imogen was keen to take the controls, and she mixed her own demos at the in‑house studio of her first record company, Rundor. "There would be a sound guy at the studio, but whenever I came they knew that they'd got the day off! They'd set me up and say 'See you at six,' and I'd get stuck in.”

She uses Pro Tools because it enables her to wield "ridiculous amounts of automation”, explaining that "At Rundor I'd literally have to get the receptionist and everybody in to do these manual desk movements and say 'Right, you do this, and you do this…' So when I got my head around Pro Tools and realised I didn't have to do that any more, I was hooked.”

As with recording and arrangement, the approach to mixing on Ellipse was very vocal‑centric. The first track to be mixed was 'First Train Home', the first single from the album. This mix became the reference point, and the vocal tracks, signal path and plug‑ins were imported into subsequent Sessions to ensure perfect consistency in the vocals throughout the album. "I thought that was quite clever!”, she laughs. Some vocal doubling effects were employed, but the main technique used to achieve the tight, thick vocal sound on the album was to edit multiple backing tracks strictly into time, and bounce them down.

Although an array of plug‑ins were used for sound design, Imogen's workhorse plug‑ins at the mixing stage were the Focusrite D2 EQ and D3 compressor, along with the Waves Renaissance Compressor. The Waves S1 was also used for stereo spreading. Imogen favours delay effects over reverb, and mainly uses the Waves Super Tap plug‑in. "I don't like reverbs; I prefer the space that you get with a delay, rather than the blanket filling up of noise you get with a reverb.”

Imogen also dislikes de‑essers, preferring to take a manual approach by editing the volume automation graph. "I'm pretty anal when it comes to de‑essing, but you can't bring up the level of the nice breathy part of the vocals if the esses are jutting out.” A trick she credits to Guy Sigsworth is to create a copy of the vocal track and manually cut out every 's' and 't'. This track is then used to feed the vocal delay effects instead of the main vocal track, preventing the hard consonants from generating overpowering echoes.

Mastering

The final mixes were digitally recorded to Alesis Masterlink, and taken to Simon Heyworth's Super Audio Mastering facility. Given that Imogen wore all the other hats during the album's production, it's almost surprising that she didn't master it as well, but she felt it was important to have at least one other person's perspective on the mixes. "I also really enjoy the ritual of going to his place in Devon and staying there for a couple of days. I love choosing the signal path with him; and l like learning. You don't feel like you're going in there on a conveyor belt like you do in some studios.”

They decided to buck the trend for squashed, heavily peak‑limited masters.

"It doesn't sound like it has that push on it, which some people may have gone for — that edgier sound. Simon doesn't square off mixes anyway, but I went with the least pushed version he did; I thought it was more true to how I listened to it here to have it more dynamic.”

Circular Thinking

Reflecting on the intense period that has been the making of Ellipse, Imogen says she'll take a different approach next time. "I'm not going to sit and work on a record non‑stop for two years ever again — it's counter‑productive. It's also counter‑creative, because you can't bounce off everything that's going on, off life. I can't go out and be social at the same time as making a record, so I'm on my own for a year. I love what I do, I love making music, and I don't want it to become something I don't want to do because it's such a big job. It doesn't have to be like that now.”

The plan is to write and produce individual songs in the course of day‑to‑day life, alongside touring, writing commissioned tracks for films, and collaborating with other artists. An album will then slowly grow over the course of three years or so, but the songs won't just be sitting around waiting. "Every time I do a song I'll release it the next day on the Internet, so it's already out there doing its thing. When I finish a song I just want it out, and not have to wait for all the promo and manufacturing; that just feels so against what it's all about today.”

Home Alone: Making An Album Solo

Producing an entire album alone had the benefit of complete creative autonomy, but there were also challenges, both production‑wise and emotionally. One of the ways in which Imogen Heap was able to get some temporary distance from the project was to bring friends down to listen to songs. Just having someone else in the room made her hear the songs differently. "It's not necessarily what they said, it's how I felt when they were in here.” Imogen sought a more direct form of feedback when she got stuck with the direction for the song 'Tidal': she put snippets of the different versions up on the Internet and held a public vote.

Another helpful dynamic was the regular presence of artist/video‑maker Justine Pearsall, who was filming a 'making of' documentary about the album, as well as shooting Heap's regular video blogs. This turned sessions into something that felt more like a performance. "I always got great stuff done when she was here. I'd moan about it, but I'd think 'What can I do for Justine today rather than sit in front of the computer?' I'd do something like get my binaural microphones and go round the house and play things.”

More difficult was maintaining the head space to keep going on such a large project, dealing with the mental chatter and expectations. "It was such an intense period. It was really emotional being down here with my thoughts. I didn't actually enjoy most of it, because you're just left to your own demons in your brain going, 'You can't do it! Don't go into the studio today, you won't be able to do anything good!'”.

Often, the messages from the connections she'd made on‑line acted as positive counterparts to her negative mind‑talk. "I'd shut the thoughts out of my head, go on Twitter and hear everyone saying, 'Go on, we love you, get on with it!' As soon I was sat down in the studio and actually working I was fine.”