John Shanks at Henson Studio C, his ‘home from home’.

John Shanks at Henson Studio C, his ‘home from home’.

Nearly 30 years after they burst onto the scene, Bon Jovi continue to top charts worldwide.

My favourite records,” says producer extraordinaire John Shanks, "are always those that are cinematic, that take you on a journey, with interesting things flying past you all the time — hooks, harmonies, melodies, counterpoints, details in the arrangements — that connect you to the lyrics and the emotion they try to convey. Everything should take you on a rollercoaster ride. The production of the new Bon Jovi album, for example, has lots of ear candy. It is full of small details coming in at various places that you're more likely to notice with headphones on. But 95 percent of the songs were written on an acoustic guitar, so they all started from that place where it's about the lyrics, the melody and the chords, and we then built them up from there. We did a lot of layering, with loads of guitars and keyboards, and loops and beats and percussion. The production is very dense, but it also feels very open.”

Shanks is talking about Bon Jovi's 12th studio album, What About Now, the band's fifth number one album in the US, and their ninth in a row to reach number one or two in the UK. The group's staggering success has been built on their capacity for marrying anthemic heavy rock with ultra-catchy melodies, which has made them, ever since their 1986 breakthrough album, Slippery When Wet, the archetypal stadium rockers. Predictably, it doesn't exactly endear them to the critics, but with an estimated 120 million album sales to date, this is hardly going to give them sleepless nights.

John Shanks, meanwhile, has, as a guitarist, songwriter and producer, been involved in over 60 million record sales, which include more than 40 number one singles and close to 100 number one albums. If this isn't impressive enough, Shanks also manages to straddle two normally mutually exclusive worlds, with pop credits including Miley Cyrus, Kelly Clarkson, Take That, Westlife, Ashlee Simpson and Backstreet Boys, and rock credits such as Van Halen, Fleetwood Mac, Robbie Robertson, Sheryl Crow, Alanis Morissette and, of course, Bon Jovi. Throw in Shanks' involvement with country acts that include Keith Urban, SheDaisy and the Wreckers, and his influence can be felt almost everywhere. Legendary record company executive Clive Davis has called Shanks' records "the sound of Top 40 radio” and credits him with being "the father of that guitar-driven kind of pop sound”. Shanks, who is originally from New York and began his music career as a guitarist in Melissa Etheridge's band, has been nominated six times for a Grammy, and in 2005 received the much-coveted Producer Of The Year award.

Jovial Crew

John Shanks's room at Henson is stuffed to the gills with guitars and other instruments. Note the wall of amplifiers to the right!

John Shanks's room at Henson is stuffed to the gills with guitars and other instruments. Note the wall of amplifiers to the right!

Shanks first joined force with Bon Jovi in 2005, when he was one of several producers on the band's studio album Have A Nice Day. He co-produced 2007's country-influenced Lost Highway with singer Jon Bon Jovi, guitarist Richie Sambora and producer Dan Huff, and two years later reunited with Bon Jovi and Sambora to produce The Circle, before recording and co-producing four new songs for 2010's Greatest Hits. What About Now is again co-produced by Shanks with Sambora and Jon Bon Jovi, and combines acoustic guitars, dulcimers, mandolins and strings with distorted electric guitars, vocals, loops and keyboards, all driven by a hard-hitting rhythm section.

A lot of the pre-production work took place at Shanks' own studio, where he keeps a huge collection of musical instruments. "Jon and Richie would come to my house, and after the songs were written, or occasionally as a starting point, we'd start programming beats and they'd play guitar, while I played guitars, bass and keyboards, and programmed loops in Logic. We laid the foundations of the arrangements for many songs in that way, with help from my engineer, Paul Lamalfe, and the album's engineer Dan Chase. That was fun, because we could experiment with different sounds and arrangements, and we could then live with the songs for a bit, and revisit them and improve them. We'd later go to the various studios, where we'd record one or two songs at a time, and then we'd add overdubs. With some of the songs for which we did programming, we overdubbed the drums to the programming, but there were also many songs that the band cut from scratch. We'd have done the demo, and would then start again, recording it with the band playing just to a click, and build a new arrangement from there. I might play guitar with them. Whether the band was playing to a click or a programmed foundation, they always began the process with playing together, approaching it like a live session.

"Hugh McDonald and Tico Torres always tracked the bass and drums playing live together, apart from in a couple of instances when we recorded Tico's drums separately. We'd always record the drums, and usually also the bass, at Jon's studio, because that room is part of the band's sound. We know the room really well, it's big with lots of natural reverb, and you can really hear the reflections. It's great for making things sound anthemic, like in a stadium, and works fantastic for a song like 'Because We Can'. Jon's studio has an SSL, and Neves, Pultecs, LA2A, LA3A, a couple of reverbs, some delays, all the solid gear that you see in most studios. The main thing is the sound of the room, and because of its ambience we record everything there that we want to sound really live, like big acoustic guitars, big background vocals, and most of Jon's lead vocals. It gives us this nice delay on his voice, rather than it just being dry. We can control the acoustics of the room by deadening it up a little, but we still get that attack, which is nice.”

Laundry Lists

For every recording visit to the East Coast, Shanks packed his Apple MacBook Pro with Logic, and would ship "a trunk with 10 or more guitars, a guitar rack with two [Lexicon] PCM42s, a Line 6 delay, a PCM80, an Eventide Eclipse, a [Empirical Labs] Distressor, tons of pedals, Neve and API mic pres, some acoustic guitars, mandolins and dulcimers, and also my Adam S4A speakers”. The laptop plays a central role in Shanks' songwriting and arranging because, he explains, "it has many of my favourite soft synths, like Lennar Digital Sylenth, Absynth, Nexus, all Tone2 stuff, especially Gladiator, the Rob Papen synths, Kontakt, and the Arturia synths, all of which I play with my Pro Control controller. I find Logic easy to use because of its drag-and-drop functions, and I can play something on a guitar or keyboard and it's very straightforward to loop it. It's very knucklehead. I get my initial ideas in Logic and when it's up and running I'll put it into Pro Tools. I'll also use a MIDI Time Piece to lock Logic up to Pro Tools, and I'll get beats going in Logic, or use the Absynth, and my Logic rig will then be like an alternate keyboard rig, because I know where all my sounds and sequencer parts are in it.”

Big trunks are clearly not necessary when Shanks works in Henson Studio C, where parts of What About Now were also recorded, as it has been his home away from home for 12 years. Shanks remarks, "I love being in my room at Henson. It's a small room, but it has an incredible sound and lots of history. It used to be called A&M studios and Joni Mitchell's Blue [1971] was done there, and Carole King's Tapestry [1971], and albums by John Lennon, Cat Stevens, Peter Frampton and the Carpenters. We can get small drum sounds there, and if I want big drum sounds I can go across the hall to studio A, B or D. I love working at my home studio, but when I really want to hear what I have, I'll go to Henson, because I know the room so well.”

As the writing and recording of What About Now progressed, Shanks's focus shifted more and more from songwriter to producer. "You take the rough mixes with you, and are listening to them over and over again, and you make notes of what needs to be done to them, like maybe the second verse could be shorter, or maybe it needs a guitar solo in a certain place, or maybe the lyrics need some lines changed. Jon and Richie make their own notes, and by the time we get back together again, each of us will have a laundry list of suggestions for changes, and when we compare them it allows us to look at each song objectively. It's almost like we're A&R-ing the record! For me, personally, because I co-write some of the songs, the more distance I have from the songs the better, so I don't think of them any more as mine or not mine. My job is simply to make every song as great as it can be. They each become like my kids, and I want them represented in the best possible light so they can reach as many people as possible.”

Missing From The Mix

Once all points in the laundry lists had been addressed, the next step was to turn the rough mixes into final mixes. Jeff Rothschild at Henson Studio C.Photo: Julian Lennon Mixer Jeff Rothschild was not initially in the picture to do this task, even though he's worked with Shanks since 2003 and has mixed much of the material that they've worked on together. Originally from New York, and developing his musical skills as a drummer in rock bands as a teenager, Rothschild obtained a degree in Music Production and Engineering at the Berklee College of Music in Boston before moving to LA, where he became a runner at Henson Studios. He assisted on sessions conducted by greats such as Don Was, Randy Staub, Bob Rock and John Shanks. Rothschild and Shanks hit it off, and Rothschild worked as an engineer on every album Shanks produced from 2003 until 2011. He also mixed most of them, though Because We Can was his first Bon Jovi mix. Two years ago, however, Rothschild decided that there was more to life than being holed up in a studio, and has been busy studying for a Master's degree in Nutritional Science and acting as a college tennis coach — "it means that I get some sunshine!” he laughs.

Jeff Rothschild at Henson Studio C.Photo: Julian Lennon Mixer Jeff Rothschild was not initially in the picture to do this task, even though he's worked with Shanks since 2003 and has mixed much of the material that they've worked on together. Originally from New York, and developing his musical skills as a drummer in rock bands as a teenager, Rothschild obtained a degree in Music Production and Engineering at the Berklee College of Music in Boston before moving to LA, where he became a runner at Henson Studios. He assisted on sessions conducted by greats such as Don Was, Randy Staub, Bob Rock and John Shanks. Rothschild and Shanks hit it off, and Rothschild worked as an engineer on every album Shanks produced from 2003 until 2011. He also mixed most of them, though Because We Can was his first Bon Jovi mix. Two years ago, however, Rothschild decided that there was more to life than being holed up in a studio, and has been busy studying for a Master's degree in Nutritional Science and acting as a college tennis coach — "it means that I get some sunshine!” he laughs.

Rothschild has nonetheless continued to mix during the last two years, albeit no longer doing 80-hour, seven-day weeks, and only on projects he really likes doing. He's recently worked on albums by Lana del Rey and Lawson, and remains closely in touch with Shanks. When Bon Jovi, Shanks and an unnamed mixer had begun the mix of What About Now at Henson Studio C, Rothschild dropped by to say hello. "We played him the mix we had of 'Because We Can',” recalls Shanks, "and Jeff came up to me and said, 'I think I can beat that.' Jon and I trust Jeff, so we said, 'OK, have a go, impress us!' We loved Jeff's mix, so we then said, 'OK, try another song.' And from there it was: 'Why don't you do the whole album?' He knows what I like, and what the band likes, and he was sending Jon, Richie and I mixes via email. We'd send him notes, and he'd apply those to the mixes. So even though the three of us weren't together for most of the mixing stage, it was a collaborative process.”

"When I first heard 'Because We Can',” elaborates Rothschild, "I thought it was such a great Bon Jovi track. I love that song and when I heard the mix that they had, to my ears it didn't quite nail it, it was missing something. I immediately knew what to do with it and what it should sound like. I felt quite strongly about that. There was no question in my mind. It's hard to describe exactly what the original mix was missing, it was a feeling and an impact thing. Mixing has an objective and a subjective aspect. The balance is an aspect of the objective part of mixing. There can't be any mistakes in a mix, and there weren't in the original mix. It was well balanced, but it just didn't have the impact that I felt it could have, with good use of compression, and EQ, and reverb and so on. Just by improving the overall tone of the mix, which is to do with the subjective side, you can give it more excitement, so you can turn the mix up and it just feels great!”

Big Drums

'Because We Can' is the opening track of and the first single from What About Now. According to John Shanks, it was written the old-fashioned way. "I think Jon played me a recording of him and Richie singing and Richie playing an acoustic guitar that they had recorded on an iPhone. It was written on an acoustic guitar, but they wanted lots of vocals on the track, and big drums. So a lot of work went into doing the drums for this song, because we wanted them to sound huge. As a result, we used Jon's studio a lot to record this song. We got Tico to play individual hits on the drums, instead of him playing a drum kit, and recorded these sounds and programmed drum parts using them. He then played live drums to these beats that had used his own sounds as samples. In addition, I added samples of a dance kick and a big, attack-y snare, to make them pop out more. Jon also sang his vocals at his studio.”

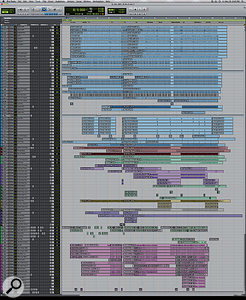

Shanks isn't exaggerating when stating that a lot of attention went into the drums on 'Because We Can': the mix session contains a whopping 40 drum tracks, in blue. In addition there are three bass tracks (in red_, 15 guitar tracks (green and purple), nine keyboard and other instruments tracks (yellow-green, white and dark purple), and 16 backing vocal tracks (pink), while the lead vocals (light green) are spread out over six tracks. This adds up to 90-odd tracks, yet Rothschild explains that "originally there were probably close to double that amount of tracks. I did a lot of bouncing in the box, like right at the bottom of the session there is a stereo bounce of 28 background vocal tracks. Among the drum tracks, just underneath the snare bottom track, there's a stereo bounce of seven loop tracks, and further down, underneath the fills tracks, a stereo bounce of six fills room tracks, and so on. They are marked as bounces in the comments column.  This composite screenshot shows the entire Pro Tools Edit window for 'Because We Can'.

This composite screenshot shows the entire Pro Tools Edit window for 'Because We Can'.

"I did these bounces where there was no reason for me to keep tracks separate, and also, I tend to use 36 Pro Tools outputs to the desk, and then about 20 faders of outboard effects. For me, that's a nice balance between submixing things in Pro Tools and still having enough options on the desk. So the first 30 minutes of a mix I spend in front of the computer screen and create a basic balance and do all these bounces, and after that I move to the desk and don't really look at the screen any more. But if necessary I can always go back to Pro Tools to adjust the balance of my bounces. The drum section of this session is atypical for a Bon Jovi because it is so extensive: in total, around 55 tracks before I bounced some of them. Usually the drum section is simpler and more compact, as in 'I'm With You', which has 21 drum tracks and six loop tracks, done by John. I did add kick and snare samples on many songs, using Sound Replacer, which are marked 'SRMM' in the Edit window waveforms.

"I have worked with the guys who recorded What About Now — Paul Lamalfe, Dan Chase, Lars Fox and Obie O'Brien — so the sessions were more or less ready to go when I received them. They didn't need much attention from me, other than the bouncing and the colour-coding. In general, after I have organised the session, bounced tracks where needed, and laid everything out over the board, I'll spend the first 15 minutes getting the song to sound more or less like I think it should sound in terms of balance, and after that it's a matter of dialling in the EQ and effects. There's a difference between mixing something you recorded yourself and something mixed by others. When I record, my rough mixes turn into the final mixes, but when I come in with fresh ears, never having heard the song before, I may be hearing it very differently, which is a risk, but it can also be good. Some people will want something that's close to the rough mix, but sometimes the rough mix was done quickly, just for people to have something to listen to, and I have a lot more freedom. It depends.

"In the case of What About Now, the roughs were really close to the way they wanted to have them, though they maybe hadn't spent a long time refining the sound. But after 10 years of working with Bon Jovi, I know what they're going for, so I could tell whether the rough was more or less where it needed to be, or not. It's a modern rock album, with a very up-front, compressed sound, which is based on a mixture of played and programmed elements, like synth basses and drum loops. But the core of it is that organic Bon Jovi feel of real people playing. People think of Jon Bon Jovi's vocals and Richie's guitar when they think of Bon Jovi, but it actually is amazing how much the drums and bass contribute to the sound. When Tico and Hugh play together, it really gives you that Bon Jovi feel, and combined with the air from them having been recorded in Jon's studio, you get the Bon Jovi sound. This album has a lot of air, which all comes from that studio, which is a killer room in the top floor of a barn. You can't fake air. DAWs have revolutionised recording, so people can make recordings in their bedrooms, but that won't allow you to make records with lots of air.

"Once I have organised the session and achieved a basic balance, I'll refine the mix and dial in the effects. Chris Lord-Alge has been a big influence on me as a mixer, and I have spent some time with him and have learnt a lot from listening to his mixes of sessions that I recorded. The difference between my rough mixes and how he then mixed the tracks was incredibly informative. He EQs everything at the same time and doesn't solo tracks, and that actually makes a lot of sense, because everything is part of a big picture. I tend to work in a similar way. I will very occasionally solo a track, just to hear what's going on, but I will rarely listen to one thing for any length of time. I also tend to EQ and work on all tracks at the same time. I'll be busy doing quick EQ corrections in the beginning, when I'm still checking what is going on on the individual tracks, usually using plug-in EQs. The vocal may have been recorded in different places and with different mics, so I may need to EQ them to make everything sound uniform. I'll also look at where the backgrounds need to sit. And you can really change the shape of a song with the way you EQ and place heavy guitars. I'll then start dialling in my delay times, just to see where these need to be. A little later, I will start automating the mix on the desk, and I'll do basic rides of reverbs and delays, which then take care of themselves. At that point, I'll look at whether the song needs additional effects, like distortion or slapback echoes on parts of the vocals. This allows the mixer to add things to the song which are unique.”

"Once I have organised the session and achieved a basic balance, I'll refine the mix and dial in the effects. Chris Lord-Alge has been a big influence on me as a mixer, and I have spent some time with him and have learnt a lot from listening to his mixes of sessions that I recorded. The difference between my rough mixes and how he then mixed the tracks was incredibly informative. He EQs everything at the same time and doesn't solo tracks, and that actually makes a lot of sense, because everything is part of a big picture. I tend to work in a similar way. I will very occasionally solo a track, just to hear what's going on, but I will rarely listen to one thing for any length of time. I also tend to EQ and work on all tracks at the same time. I'll be busy doing quick EQ corrections in the beginning, when I'm still checking what is going on on the individual tracks, usually using plug-in EQs. The vocal may have been recorded in different places and with different mics, so I may need to EQ them to make everything sound uniform. I'll also look at where the backgrounds need to sit. And you can really change the shape of a song with the way you EQ and place heavy guitars. I'll then start dialling in my delay times, just to see where these need to be. A little later, I will start automating the mix on the desk, and I'll do basic rides of reverbs and delays, which then take care of themselves. At that point, I'll look at whether the song needs additional effects, like distortion or slapback echoes on parts of the vocals. This allows the mixer to add things to the song which are unique.”

Drums: Euphonix compressor & EQ, SPL Transient Designer, Pultec EQP1A, Neve 33609, Avid Sound Replacer, EQ7 & Long Delay, Waves L1 & API 550, Lexicon 300 & PCM42, AMS RMX.

"I had one kick channel on the Euphonix desk, and one snare channel, so I was submixing the many kick and snare tracks in the 'Because We Can' session inside of Pro Tools. Almost all drum elements were submixed to a channel pair on the desk. I like to keep it simple! I added one kick and four snare sample tracks using Sound Replacer, just to get more of the attack and bite that you need on a modern rock record. The letters in the 'comments' column are a reference to the samples I used. For outboard on the kick and snare, I will have used the Transient Designer, and a Pultec EQP1A, and I may have had a subcompression group with the Neve 33609. I also multed the snare to two other channels, one that's really compressed to the point where it is distorted, using the desk compressor, and one that's really bright, and I ride these channels throughout the song as needed, to help the snare cut through. This is something I learned from Tom Lord-Alge.

"As you can see in the session, I used few plug-ins, and there were none on the kick and snare, apart from the API 550 on the snare master track. The other plug-ins I used on the drums in this session were the Digidesign EQ7 on the hats, the L1 and the API 550 on the overheads, the L1 on a fills track, the EQ7 on some toms, the L1 on the loops, and the Long Delay on the closed hat. The API 550 and the L1 are often used in this session because they are my favourite plug-ins. They give me everything I really need from plug-ins. I'm a big fan of the API plug-ins, and for me, the L1 is all about tone. It makes things louder, but it also has a distinct sound, and that's primarily why I use it so much. My drum reverbs came from a Lexicon 300 with a room sound, the AMS RMX non-linear, and I may have had the Lexicon PCM42 on the snare as well.”

Pitched instruments: Waves LA2A, API 560 & L1, Dbx 160, Pultec EQP1A, Altec compressor, Euphonix compressor & EQ, Urei LA3A, API 550, Roland SDE3000.

"There are three bass tracks: a real bass and two synth basses. These actually came up on three different channels on the board. I had LA2A and API 560 plug-ins on the real bass, and outboard would have been Dbx 160 and a Pultec EQP1A and an Altec compressor. The synth basses had some desk compression, just to rein in notes that jumped out, but you don't usually need to do much with synth sounds. The two acoustic guitars, the 12-string guitar and the dulcimer added a lot of texture to the song, and all came up on two channels on the desk, on which I treated them with an LA3A outboard and some desk EQ. One of the two acoustic guitar tracks had API 550 and L1 plug-ins in it. The purple guitar tracks are the electric rhythm guitars and they came up on three pairs of channels on the desk, on which I again had an outboard API 550 and some desk compression. The green tracks are the solo electric guitars, including some solo harmony licks, doing that Brian May kind of thing. These all came up on channels 15 and 16 on the desk, and would have had desk compression and EQ. I also had a delay on the guitar solo tracks, using a pair of Roland SDE3000s. The piano had its own two channels, as did the padding instruments such as the [Suzuki] Omnichord and the keyboards, including the cello sample track, which all came up on a stereo pair on the desk. I had API 550 and L1 plug-ins on the piano track, and the same on the cello, and for the rest I used desk compression and EQ. I don't use reverb or delay on padding instruments.”

Vocals: Waves API 550, L1, De-esser, C4, Metaflanger, Doubler & L1, Lexicon PCM70, Roland SDE3000, Yamaha SPX90 & Rev 5, Lexicon PCM42, Line 6 delay, Focusrite EQ, Smart C2, Behringer Ultrafex, Eventide H3000.

More guitar amps in John Shanks's studio!

More guitar amps in John Shanks's studio!

"There are two ad lib lead vocal tracks, and four main vocal tracks. The top two may have been recorded on different days, needing slightly different EQ, and the two tracks below that came into being because I pulled down certain words and phrases that I felt needed a different treatment. There are several plug-ins and loads of outboard on the lead vocals. The plug-ins are the API 550 and L1 for tone, and the Waves De-esser, nothing crazy. There's also a Waves C4 to take out some mid-range. It's a compressor, but it functions as an EQ. The outboard comes from two Lexicon PCM70s, two Roland SDE3000s, a Yamaha SPX90 and Rev 5, a Lexicon PCM42, and a Line 6 delay. The SDE3000s gave me eighth-note and dotted eighth-note delays, panned left and right for that stereo thing, and the Line 6 box gave me a lo-fi quarter-note mono delay. One PCM70 was set to a plate reverb and the other PCM70 to a concert hall, and I used the SPX90 for its pitch-change program, +8 [cents] on one side and -8 on the other. You can use a plug-in, but the SPX90 has a distinct sound, and I'm a big fan of it. It widens and fattens the vocal, and results in a tone that I like. Then there's a small slap echo from the PCM42 and an early reflections short room from the Rev 5. It sounds like a lot, but all these effects have their place and they are all ridden throughout the song.

"There also are loads of backing vocals, which came up on three stereo pairs on the desk, channels 17-22. I combine the backing vocal elements that match in Pro Tools, like all the chorus vocals, if they need to be part of the same blend. I had a Focusrite EQ plug-in on one of the backing vocals, probably just to correct something. Because the backing vocals were combined on the desk, I could use outboard over several tracks, like the Alan Smart C2 compressor, the Behringer Ultrafex for a stereo imaging thing to spread the vocal group out, and the Eventide H3000 for a similar pitch-shift effect as I did with the SPX90 on the lead vocals, +8 on one side and -8 on the other, though it sounds totally different. I probably also put that through an SDE3000 to get a ping-pong delay. The bounce of 28 vocals tracks at the bottom has four plug-ins: the Metaflanger, a Focusrite, Doubler, and the L1. It creates a mid-range telephone effect that occurs in the middle of the chorus.”

Mixdown: Waves Pultec EQ, L3 & L1, Avid Maxim.

"I mixed back into the session, which was in 44.1/24. It makes no sense to record in 48 or 96, unless it's for a movie, and I think that you can only justify going to 88.1 if you're recording a classical record or something with only acoustic guitar and vocals. On this record, there was so much stuff going on that you won't hear the difference between 88.2 and 44.1. The mix came back into the session on the bottom track, which has four plug-ins, the Pultec EQ, the L3, the L1 and the Maxim, and it was then printed on the track next to it. All these plug-ins are doing subtle things, but together they changed the sound so much that I had to leave them in when I sent the mix to mastering. The plug-ins are partly there for tone, but you also need to make your mix loud, because rough mixes are getting louder and louder and brighter and brighter. This can be a real problem for mixers, as it ties your hands: you have to come in at least as loud and bright as the rough mix! I'm really proud of this record, and particularly this song, which is one of my favourite mixes.”

John Shanks is also proud of Because We Can, despite a lukewarm critical reaction. "There's always this funny thing that if the critics like it, it doesn't sell, and if they don't like it, it'll be a number one. You can't please everybody, so you may as well please yourself. You want people to listen objectively to a record you've made, and not just cherry-pick and only listen to the single. You want them to go in and listen to the entire album, which is a body of work. Albums are time capsules, and this is where Jon, Richie and the band were at when we recorded the album, and I'm really proud of it. I stand by this record. I've been doing this for a long time, and I listen to everyone else's records, and I feel that this is really good. It's a strong body of work. I know that Jon is proud of the album, and so he should be. These guys do great work, and I am honoured that they trust me to continue the journey with them.”

The Pros Of Digital Control

Like John Shanks, Jeff Rothschild works at LA's Henson Studios all the time, and he has come to depend on Studio C's Euphonix desk. "Probably 95 percent of the records I have mixed while working with John I did at Henson Studio C, and I mixed What About Now there in its entirety. I live just five minutes from the studio, so I could come in and out when I liked. I did a mix a day, and then waited for feedback. There was quite a bit of going back and forth, but because the Euphonix desk is a digitally controlled analogue desk, the mixes would come back instantaneously. It's a great desk that wasn't well-received at the time it came out, because back then people weren't used to working on assignable digital surfaces. But if it came out now, it'd be all the rage. I believe that it was 10 years ahead of its time. It sounds great, and is very easy to use. The desk has 48 channels that you can split, so it's actually 96, and each channel has two EQs and a compressor, which are very transparent and don't add a lot character, but they are very effective and smooth-sounding. As you can see from the screenshots, I don't use many plug-ins during the mixes, and the nice thing about having mixed in one place for so long is that all the outboard is permanently plugged in on certain channels, so it's easy for me to get everything back to where I was. I haven't changed patch cables in five years! When I was younger, I used to baulk at people who had permanent systems and setups, like always having the same vocal chain, but over the years, you work out what works and what each box will give you, and you develop a method.”

Shanks On Songwriting

"With this record, Jon [Bon Jovi] really wanted to take his time writing, so we took eight months on and off to write the album,” explains John Shanks. "The entire making, including recording, took about a year, starting in October 2011. We wrote and recorded in many places, including my home studio, Henson Studio C [both are in LA], Jon's apartment in New York and his studio in New Jersey, and Electric Ladyland and Germano Studios in New York. The songs Jon and I, sometimes with Richie [Sambora], wrote for the album were often written at Jon's apartment or at my home studio, with one or two guitars and a piano, a legal pad, and us recording things into a cassette player or an iPhone. We'd sit together and really hone the lyrics as well as the music. We really aimed for the songs to have depth, and I really like the vulnerability and realism in the lyrics.

"I have written songs every different way, just by picking up a guitar and starting from there, or beginning with a small figure on the piano, or with soft-synth sounds and/or a beat in Logic. You write a different kind of song when you're writing with a DAW. You tend to have less chord changes, whereas when you write on an acoustic guitar, you want to move chords more often and this also pushes you to create more melodies. How I write depends who I am working with. I'm about to do a Colbie Caillat record, and that's old-school writing, us sitting with acoustic guitars and feeding off each other. When I wrote with Gary Barlow of Take That, we were writing with an acoustic guitar and piano, and once we had the song, we'd go into the studio to make the record. I'm happiest when I'm in that songwriting mode, and the things that are in your head are coming out. It's really exciting and to my mind usually produces the best songs.”