Lalah Hathaway

‘Little Ghetto Boy’

Although everything about this Grammy-winning live performance oozes effortless class, it’s the vocal that provides the real magic. One aspect of Hathaway’s technique particularly impresses me, and that’s her treatment of long sustained notes. There are plenty of R&B divas who lack the conviction to stay put on a given pitch for any length of time, retreating into blizzards of emotionally vacuous curlicues at every opportunity — their fear, presumably, being that they’ll lose the listener’s attention otherwise. What Hathaway so splendidly demonstrates here is that there’s plenty of scope to hold the ear with timbral variation alone. The word “boy” at 0:50 is a case in point. By virtue of her extending the vocal diphthong, you effectively get a slow transition between ‘o’ (as in ‘top’), though ‘e’ (as in ‘set’), to ‘ee’ (as in ‘see’), creating a kind of timbral momentum through the arrangement drop-down at that point. Likewise, the word “door” at 1:51 goes from ‘o’ (as in ‘top’), through ‘er’ (as in ‘her’), to ‘a’ (as in ‘hat’); and the word “sing” at 1:00 sustains the ‘ng’ almost into an additional syllable.

Not that Hathaway’s style is without ornamentation, but it’s economical and unfussy, often just simple mordents (eg. “street” at 0:25, “misery” at 1:05, and “sad” at 1:25); little upward scoops at note onsets (eg. “face” at 0:33, “got” at 1:42, and “boy” at 2:21); or tiny scalar fall-offs (eg. “be” at 0:57, “go” at 1:45, and “man” at 2:27). And she doesn’t just rely on flurries of notes to enhance her expression. Take, for example, the added articulations on “gr-o-ce-ry sto-o-(h)ore” and “and i-it, and it ai-ain’t gonna change” (at 1:20 and 1:36 respectively), or the sudden stressed and extended-duration high-register notes on “how rough” and “don’t you know” (0:54 and 1:22). Because of this restraint, her first real ad lib (the “eh-heh” at 2:33) actually feels like an important event, and the subsequent improvisatory outro section also provides a natural step up in performance intensity, as you’d hope. Mike Senior

Little Big Town

‘Girl Crush’

It’s not easy to find a new angle on the classic 6/8 country ballad formula, so I can’t help admiring the way Little Big Town have refreshed it here with an inspired combination of quirky instrument sounds. Right from the outset the obligatory arpeggiated guitar is garnished with a deliciously strange slapback echo reminiscent of water dripping. Between that, the achingly glistening lead vocal and the supporting backing vocals, there’s plenty to hold the attention well past the end of the first minute, until that magic moment when the specks of tuned percussion (celeste and vibraphone, I’d guess) start arriving at 1:16. Then the crusty drums shuffle into the second verse like some kind of shy trip-hop refugee, followed not long after by querulous, almost otherworldly little Hammond stabs. And gluing it all together is a constellation of Nashville’s most tastefully understated backing sweeteners — rich bass guitar, oh-so-subtle clean guitar layers, and a variety of cockle-warming keyboard fillers.

It’s not easy to find a new angle on the classic 6/8 country ballad formula, so I can’t help admiring the way Little Big Town have refreshed it here with an inspired combination of quirky instrument sounds. Right from the outset the obligatory arpeggiated guitar is garnished with a deliciously strange slapback echo reminiscent of water dripping. Between that, the achingly glistening lead vocal and the supporting backing vocals, there’s plenty to hold the attention well past the end of the first minute, until that magic moment when the specks of tuned percussion (celeste and vibraphone, I’d guess) start arriving at 1:16. Then the crusty drums shuffle into the second verse like some kind of shy trip-hop refugee, followed not long after by querulous, almost otherworldly little Hammond stabs. And gluing it all together is a constellation of Nashville’s most tastefully understated backing sweeteners — rich bass guitar, oh-so-subtle clean guitar layers, and a variety of cockle-warming keyboard fillers.

Were it not for Ed Sheeran’s ‘Thinking Out Loud’, this song would have been easily my favourite ballad of 2015. A vintage year! Mike Senior

Alabama Shakes

‘Don’t Wanna Fight’

The ethos of experimentation that Alabama Shakes’ production team talked about back in SOS July 2015 clearly paid dividends — not since Anastasia’s ‘I’m Outta Love’ have I heard such a show-stopping vocal opener as this. It sounds like Macy Gray’s caught something sensitive in her zip! And aside from its sheer ‘what the...?’ impact, that kettle-just-boiling squeal is also tremendously effective as a contrast to the main vocal timbre that arrives three seconds later, serving to emphasise the earthy gutsiness that’s practically a Brittany Murphy trademark. The vocal gymnastics don’t end there, either, because the chorus then pushes into a completely different pitch register. Somewhat outside the singer’s comfort zone, clearly, but there’s no harm in that when it results in something as ear-catching as this.

The ethos of experimentation that Alabama Shakes’ production team talked about back in SOS July 2015 clearly paid dividends — not since Anastasia’s ‘I’m Outta Love’ have I heard such a show-stopping vocal opener as this. It sounds like Macy Gray’s caught something sensitive in her zip! And aside from its sheer ‘what the...?’ impact, that kettle-just-boiling squeal is also tremendously effective as a contrast to the main vocal timbre that arrives three seconds later, serving to emphasise the earthy gutsiness that’s practically a Brittany Murphy trademark. The vocal gymnastics don’t end there, either, because the chorus then pushes into a completely different pitch register. Somewhat outside the singer’s comfort zone, clearly, but there’s no harm in that when it results in something as ear-catching as this.

Another fascinating sonic element here is the opening dual-guitar texture, which feels almost supernaturally wide in stereo, but without using any fancy out-of-phase shenanigans — soloing the left and right channels independently, it’s clear that all we’re hearing is hard-panned mono signals. However, each channel does have that kind of ‘static flange’ timbre I associate with comb-filtering, which suggests one plausible explanation for the image width. Let me explain.

Even with separate instruments panned to opposite extremes, there will almost always be some frequencies that both instruments are both putting out in phase at any given moment, effectively panning the combined energy at those frequencies towards the centre. Although the specific frequencies narrowed in this manner will constantly be changing, on average this unpredictable phenomenon will tend to narrow the mix a touch. However, imagine that you notch a narrow frequency band out of the left channel — it would avoid that spectral slice ever being pulled towards the centre, albeit at the cost of nailing that slice to the right-hand speaker. Then, naturally, you’d want to notch a slightly different frequency in the right channel to rebalance the stereo image overall. The result: a mix where more of the frequency energy remains at the stereo extremes, and which therefore feels subjectively wider.

Even with separate instruments panned to opposite extremes, there will almost always be some frequencies that both instruments are both putting out in phase at any given moment, effectively panning the combined energy at those frequencies towards the centre. Although the specific frequencies narrowed in this manner will constantly be changing, on average this unpredictable phenomenon will tend to narrow the mix a touch. However, imagine that you notch a narrow frequency band out of the left channel — it would avoid that spectral slice ever being pulled towards the centre, albeit at the cost of nailing that slice to the right-hand speaker. Then, naturally, you’d want to notch a slightly different frequency in the right channel to rebalance the stereo image overall. The result: a mix where more of the frequency energy remains at the stereo extremes, and which therefore feels subjectively wider.

Now scale that up to use masses of different EQ notches per channel, rather than just one, and the width-enhancement strengthens. If that sounds like a lot of work, though, never fear — comb-filtering generates a whole series of different EQ notches at a stroke by its very nature. Which brings me back to what I’m hearing on ‘Don’t Wanna Fight’. I reckon each guitar has some degree of comb-filtering on it, but each part affected at different frequencies, and that’s what’s enhancing the apparent stereo width in this case. What’s causing the comb-filtering is another question, of course. I can only guess... While it could feasibly be a dedicated stereo-widening plug-in, it’s just as likely to be some kind of sub-10ms delay effect (such as a static flange) or merely the outcome of combining multiple mics set up at different distances from the amp during tracking. Mike Senior

Ghost

‘Cirice’

Whether or not you can keep a straight face through Ghost’s stage act, there’s nonetheless plenty to recommend this Swedish metal band’s Grammy-winning US breakthrough single on a musical level. It’s very cool the way they give the song’s hook line (first heard on “can you hear the thunder” at 1:31) a new lease of life halfway through the song by tacking an extra half-bar onto the first phrase (“...in your heart”) and reharmonising the backing parts to include a couple of euphoric major chords. The second of these, the C major first heard at 2:22, has the added benefit that its E creates a whacking great false relation against the root of the following Eb major chord — and few people like false relations more than musicians with long-term face-paint-related acne. Mike Senior

Whether or not you can keep a straight face through Ghost’s stage act, there’s nonetheless plenty to recommend this Swedish metal band’s Grammy-winning US breakthrough single on a musical level. It’s very cool the way they give the song’s hook line (first heard on “can you hear the thunder” at 1:31) a new lease of life halfway through the song by tacking an extra half-bar onto the first phrase (“...in your heart”) and reharmonising the backing parts to include a couple of euphoric major chords. The second of these, the C major first heard at 2:22, has the added benefit that its E creates a whacking great false relation against the root of the following Eb major chord — and few people like false relations more than musicians with long-term face-paint-related acne. Mike Senior

Classic Mix

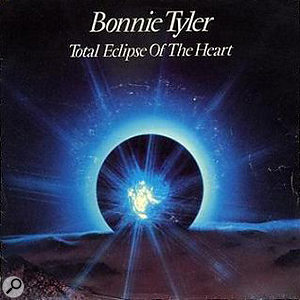

Bonnie Tyler ‘Total Eclipse Of The Heart’ (1983)

Bonnie Tyler’s tremendously ragged vocal timbre is a saving grace of this production, which might otherwise have descended into pure bathos under the weight of Jim Steinman’s production histrionics and a snare reverb as synthetically bouffant as the singer’s 1984 Grammy Awards hairdo. The progressive unveiling of her high pitch register is also well paced, with each new section reaching a fresh peak. So in the opening verses we get up to G#, before pushing further to C in the first chorus. Then the following verse hits a ferociously phlegm-spattered C# in its final moments, before the chorus inches first to D for “giving off sparks” and, finally, to the crowning Eb, which hammers home the last “I really need you tonight”. But it’s not just the high registers that are used strategically, because Tyler’s lowest notes are kept back exclusively to distinguish the title hook.

Bonnie Tyler’s tremendously ragged vocal timbre is a saving grace of this production, which might otherwise have descended into pure bathos under the weight of Jim Steinman’s production histrionics and a snare reverb as synthetically bouffant as the singer’s 1984 Grammy Awards hairdo. The progressive unveiling of her high pitch register is also well paced, with each new section reaching a fresh peak. So in the opening verses we get up to G#, before pushing further to C in the first chorus. Then the following verse hits a ferociously phlegm-spattered C# in its final moments, before the chorus inches first to D for “giving off sparks” and, finally, to the crowning Eb, which hammers home the last “I really need you tonight”. But it’s not just the high registers that are used strategically, because Tyler’s lowest notes are kept back exclusively to distinguish the title hook.

In terms of harmony, this song is curiously (though effectively) rather bipolar: while the verses are unstable and modulatory, flitting jarringly between suggestions of Bb minor, C# major and E major, the chorus settles into a more conventional Ab major workout to support the expansiveness of the lead melody. Of course, it helps in this context that the chorus kicks off with one of the hoariest old harmonic chestnuts ever, that repeated I-VI-IV-V pattern that’s been the darling of ballad-writers for generations, perhaps most famously illustrated in Whitney Houston’s ‘90s smash-hit reworking of Dolly Parton’s ‘I Will Always Love You’. (The chorus in Houston’s version, incidentally, exhibits such striking similarities in tempo and melodic contour to ‘Total Eclipse...’ that it’s surely a viral mashup sensation in waiting!)

Other indicators abound of experienced song-writers at the helm. Notice, for instance, how the line “total eclipse of the heart” is a thinly veiled octave-down reworking of the opening chorus melody (first heard on “and I need you now tonight”), its provenance hammered home by the instrumental restatement which immediately follows in the piano accompaniment. Why invent something new when you can better cement the material you already have in the listener’s mind instead? Those two extra beats of phrase extension after the second “giving off sparks” likewise bear testament to a sure hand on the tiller, ratcheting up the tension one more notch into the song’s climax.

But my favourite moment has to be the way the two-part harmony of “now I’m only falling apart” converges to unison double-tracking for “total eclipse of the heart”, a move which begs so strongly to be interpreted as an ‘eclipse’ of the backing vocal behind Tyler’s louder and more characterful lead line that I can’t believe it wasn’t conscious word-painting. Mike Senior