Rather appropriately, we round off this series by looking at what you need to consider when composing music designed to play while the end credits roll...

Last month I introduced a documentary film for television, Dinka Diaries, and made three scenes available for you to score. In this, the final instalment of this series, we'll look at how I scored these scenes, and consider music for the closing credits of programmes and films. I'll also try to explain the importance of backing up your work, and the significance of stem mixes of your finished scores.

Mission Accomplished

One of the most challenging aspects of composing using a computer is to have your tracks sound as if they were played by real musicians (assuming you are playing all the parts yourself with virtual instruments, which I do most of the time). I avoid quantisation whenever possible, which goes a long way towards meeting that goal. In Part 7 of this series, I discussed using tempo changes and markers to assist in accommodating picture edits. However, there are times when it can be far more effective to rely on the old-fashioned approach of simply playing along with the video. And that's just what I did with the first of the three scenes I introduced last month (you can view the finished scene with music at ![]() dinkaphotosafterfinal.mov .

dinkaphotosafterfinal.mov .

The finished musical arrangement for the 'Village Elder' section of Dinka Diaries, as seen in Pro Tools. Note the lines denoting the edits in the second guitar part, where it has been assembled from multiple takes.I established last month that the director of Dinka Diaries, Filmon Mebrahtu, wished to use a nylon string guitar and a string orchestra. Having thought up some harmonic changes, I rehearsed my guitar part while viewing the picture. It was important that I didn't play too busy a part, as I didn't want to distract from the dialogue. By closely following the picture and listening to the dialogue, I was able to create a part that flows in a way that would be difficult to create with a click track or tempo map. The slight tempo variations add a distinctive human element. Once I had recorded this part while playing along with the picture, I loaded strings from the Vienna Symphonic Library (VSL) Opus 1 collection into Native Instruments' Kontakt and played to the tempo established by the guitar.

The finished musical arrangement for the 'Village Elder' section of Dinka Diaries, as seen in Pro Tools. Note the lines denoting the edits in the second guitar part, where it has been assembled from multiple takes.I established last month that the director of Dinka Diaries, Filmon Mebrahtu, wished to use a nylon string guitar and a string orchestra. Having thought up some harmonic changes, I rehearsed my guitar part while viewing the picture. It was important that I didn't play too busy a part, as I didn't want to distract from the dialogue. By closely following the picture and listening to the dialogue, I was able to create a part that flows in a way that would be difficult to create with a click track or tempo map. The slight tempo variations add a distinctive human element. Once I had recorded this part while playing along with the picture, I loaded strings from the Vienna Symphonic Library (VSL) Opus 1 collection into Native Instruments' Kontakt and played to the tempo established by the guitar.

The second scene required two acoustic guitars to 'converse', played in the style of the late North African blues guitarist Ali Farka Touré. This was the most challenging piece for me — I dread to think what it must have been like for those of you who are not guitar players — and I found it hard to get it 'just right'. As with the first piece, I played the guitar while viewing the picture and listening to the dialogue. This was actually the fourth of five scenes in the documentary where music accompanies one of the youths while they are listening to a Sudanese village elder on headphones. I recorded a number of different ideas on the guitar for Filmon to choose from, built from thematic riffs that I had already established by this point in the scoring process. Once I had the first guitar recorded, I proceeded to play the second part. Listening carefully to both the dialogue and guitar, I played a track that complemented the first part, featuring more improvisation. I recorded a number of takes of the improvisation, and as you can see from the screenshot on the right, the final track was edited together from several of these takes. You can download the finished scene from the film, with its completed music, at ![]() villageelderafterfinal.mov.

villageelderafterfinal.mov.

The third and final scene featured a map, and like the other map scenes in the film, this one needed some rhythmic movement. I turned to East West's Ra, which offers a number of authentic African percussion instruments to choose from. The first instrument loaded was an African metal shaker, which provided the pulse. Next I added a kalimba, which served as a melodic element as well as reinforcing the pulse. I also added a xylophone from my VSL Opus 1 library to double the kalimba part, fading it in and out of the track. This added a thickening to the kalimba part that I liked. Finally, with the percussion in place, I loaded up the string orchestra from the Opus 1 library. It's interesting to note that as the Kalimba is playing an ostinato part, it helps to serve as a neutral foundation and a balance against the strings, which adds a more serious tone to the maps. Depending on the instructions from the director, I am always careful not to inject my personal feelings into the score. And that's not easy when the subject matter is controversial. In this case, I was able to strike the right balance between the seriousness of the situation being discussed and the neutral intent of the director. You can hear the final clip at ![]() dinkamapafterfinal.mov

dinkamapafterfinal.mov

Upon completion of the score, Filmon asked me to provide stem mixes, so that he could control the balance between the strings, the guitars, and the percussion. To learn more about this, see the box about stems on the next page of this article.

Every scoring project will have its own set of circumstances, and Dinka Diaries proved to be a significant challenge. But sometimes the most rewarding projects are the ones that challenge us the most, and in the process, teach us something we didn't previously know anything about. In the end, the director was extremely happy with the music, which is all that really matters, and I certainly learned something new by having to explore the music of Ali Farka Touré.

Classical Inspiration

This series has given you some suggestions about contemporary film composers to listen to, as well as the great masters who developed the art form. But who do the great film composers listen to? Where do they get their inspiration? Typically, they listen to works of the great classical composers. And while it's not unusual for classical music to be used in films and on television, let's not forget that many classical composers wrote specifically for the medium, among them William Walton (Henry V), Ralph Vaughan Williams (Scott Of The Antarctic), Malcolm Arnold (Bridge Over The River Kwai), Dmitri Shostakovich (The Fall Of Berlin), John Corigliano (Altered States) and Aaron Copland (Of Mice And Men).

If you like Samuel Barber's Adagio For Strings (used, of course, in Oliver Stone's film Platoon), I think you'll love Musica Celestis by Aaron Jay Kernis. Kernis is a gifted composer whose symphonic works seem very 'cinematic' — to me, at least. And if you're a fan of Ridley Scott's Alien, as I am, you probably loved Jerry Goldsmith's masterful soundtrack. The music that accompanies the climactic scene where the alien is blown out into space at the end of the film, however, is not Goldsmith's music, but the end of the first movement of Howard Hanson's second symphony (also called Romantic). The music continues on through the closing credits, and it's hard to believe Hanson didn't write the music just for this film, as it works perfectly.

Besides the obvious composers to listen to (Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Strauss, Ravel, Debussy, Holst, and Wagner were all highly imaginative and adept at creating evocative music that lends itself well to accompanying film, which is perhaps why their works are used so often), consider the music of 20th-century composers such as John Adams, Henryk Gorecki, Béla Bartók, Philip Glass, Jennifer Higdon, Jean Sibelius, Igor Stravinsky, Charles Ives, Libby Larsen and Alban Berg (particularly the latter's violin concerto).

Here Today...

Recently a fellow composer called me with some very bad news. His main audio drive had failed, and he had not backed it up in over a year or more, so virtually all the audio from his recent projects was now lost. This was a hardware failure, so available software fixes were ineffective, as he could not mount the drive on the desktop. It may seem hard to believe that he had not made any backups over such a long period of time, but the story is true, and he has learned a painful lesson. It remains to be seen whether or not all of his files can be recovered. The only course of action he can attempt now is to take the drive to a data-recovery service — and of course, there is no guarantee that he will successfully recover his data at the end of it. What's more, data recovery is an extremely expensive option. You literally don't want to go there.

I didn't get where I am today without... lots of backup drives. But just to prove that no-one's perfect, as I write this, I'm trying to recover some lost data from a crashed drive. And of course, as luck would have it, the drive that's crashed is the only one that wasn't fully backed up...If you want to make a living working in film and TV, you'll need to adapt some backup strategies to prevent such a disaster from happening to you. Archiving of data is an essential part of a professional workflow; clients will not tolerate delays, and wholesale loss of data can rapidly lead to the loss of a job.

I didn't get where I am today without... lots of backup drives. But just to prove that no-one's perfect, as I write this, I'm trying to recover some lost data from a crashed drive. And of course, as luck would have it, the drive that's crashed is the only one that wasn't fully backed up...If you want to make a living working in film and TV, you'll need to adapt some backup strategies to prevent such a disaster from happening to you. Archiving of data is an essential part of a professional workflow; clients will not tolerate delays, and wholesale loss of data can rapidly lead to the loss of a job.

Of course, backing up isn't very easy (which is perhaps why so many people don't do it). File sizes for musical projects can be rather large, and Quicktime video files only add to that. To give you an example, the size of my Pro Tools project folder for Dinka Diaries was in excess of 10GB, and the video files were 13GB. Managing files of this size can be a tall order, and you need to consider many factors, such as how much suitable backup hardware will cost, and how long it will take to back up your current projects with it, before you make your final decision.

The following strategy works well for me (but your mileage, as ever, may vary). The quickest way to back up data at the end of a session is to copy files to a spare external Firewire drive, and fortunately, the cost of such drives is fairly reasonable these days. My first ever hard drive had a capacity of 30MB (yes, that's Megabytes, not Gigabytes...) and it cost me 800 dollars (about £450). These days, you can't even get RAM that small any more. In the USA, the current cost is around a dollar per Gigabyte of external Firewire hard drive space, but this is just as well — as a hard-working music-for-picture composer, you'll need access to hundreds of Gigabytes of storage, probably split across many drives, to house all the variations on your work that you may need to create, to say nothing of the space you need for modern sample libraries. It's true what they say — you never can have too much hard drive space. In addition to a rack of hard drives (shown in a picture earlier in this article), I keep a completely separate 500GB drive just for temporary backups. For approximately the cost of a synth plug-in, I have a reliable and quick means of backing up my current projects.

As I get further into a project and a window opens long enough to take a break, I'll make a temporary archive to DVD. DVDs can hold just over 4GB of data, and now that high-speed DVD burners are standard in most modern computers, it doesn't take that long to burn a disc. Things get more complicated as I move beyond the capacity of a single DVD. Fortunately, Roxio's Toast 7 software for Mac has a great solution, a feature called 'data spanning', which allows you to archive (say) a video file which is too large for one disc across a set of DVDs. The set can then be used to restore the file later — provided you don't lose any of the discs! My Dinka Diaries project is spread out across three DVDs for the Pro Tools session and four DVDs for the video file.

At the end of a project, I make at least two sets of backups to DVD. For me, this is the best solution, combining speed and low cost. No archive medium is completely foolproof, whether it's a DVD, a hard drive, a CD-R, or a tape-based system; there will always be a risk that some defect may exist with your backup of choice. So the more backup copies of your project you make, the more you minimise the risk of not being able to recover your data. And any backup is better than no backup, as my friend has discovered. Sooner or later your drives will fail, and whenever it happens, it's going to be at a bad time (after all, when would be a good time for a drive to fail?). Minimising the damage when the time comes is up to you as a responsible, professional composer.

The Importance Of Stems

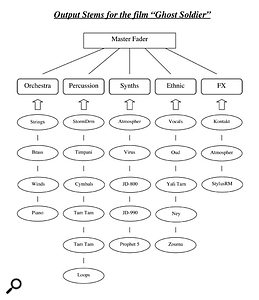

Audio stems supplied to the director of Ghost Soldier, the film mentioned in Parts 6 and 7 of this series, to allow for greater control when mixing the soundtrack. In the film and television world, it is often required that in addition to providing your clients with a stereo mix, you also provide stems, or split mixes. These are premixed files, often in stereo, that usually contain all of the instruments of a certain type (for example strings, drums, or guitars) to facilitate greater flexibility when mixing. However, the exact configuration can change depending on the type of music, its complexity, and the requirements of the post-production audio mixer. When called upon to provide stems, I usually make separate stereo mixes of percussion instruments, symphonic instruments, synths and finally sound-design elements. For the film Ghost Soldier (covered in parts 7 and 8 of this series), I also added a separate stem of ethnic instruments (see the diagram below).

Audio stems supplied to the director of Ghost Soldier, the film mentioned in Parts 6 and 7 of this series, to allow for greater control when mixing the soundtrack. In the film and television world, it is often required that in addition to providing your clients with a stereo mix, you also provide stems, or split mixes. These are premixed files, often in stereo, that usually contain all of the instruments of a certain type (for example strings, drums, or guitars) to facilitate greater flexibility when mixing. However, the exact configuration can change depending on the type of music, its complexity, and the requirements of the post-production audio mixer. When called upon to provide stems, I usually make separate stereo mixes of percussion instruments, symphonic instruments, synths and finally sound-design elements. For the film Ghost Soldier (covered in parts 7 and 8 of this series), I also added a separate stem of ethnic instruments (see the diagram below).

As you can probably imagine, generating all of these mixes can be time consuming. So why do it? The goal is to give the audio mix engineer the ultimate in flexibility when balancing music with dialogue, ambience and effects. Be sure to have what is known in movie-speak as a 'two beep' (a 1KHz tone lasting the duration of one frame of video), or at least a count-off, at the beginning of each stem mix, so that the mix engineer can precisely synchronise all of your stem files. At the very least, make sure your stems all start at exactly the same frame!

At the beginning of a scoring session, I'll often set up Aux channels to accommodate the stems. Sometimes I'll even create sub-stems that are routed to the main stem. For instance, I often create separate sub-stems for brass, strings and woodwinds, which are all routed to the main orchestra stem. Another advantage of configuring a session this way is that it makes it easy to control the overall level of your session. Reaching for the master fader and pulling that down is not always the best solution; but when your session is set up in the way I've described, it takes just a few moments to drop a Trim plug-in across all of your stems and pull everything back a decibel or two. One final note of caution: be sure to set up your reverb and effects so that they are routed to the appropriate stems. I typically use separate reverbs for each stem. You can get around this by bouncing each stem separately with effects, but this is very time consuming and you lose flexibility. In Pro Tools, I'm able to bounce all of my stems to individual audio tracks at the same time.

Closing Credits

So, you've written your cinematic masterpiece, and you've come to the end of the film. What next? It's time once more to engage in the art of persuasion, and convince your employer of the importance of using more of your music while the credits roll past.

This may be harder than you think. There's no shortage of people who want to get their music into films, and many of them offer their music for free just for the privilege. What's more, the closing credits traditionally provide a producer with a great opportunity to reward someone for investing in the film, to satisfy a promise to a distant cousin, or to repay that friend who loaned him the use of his beach house for a weekend. It even gives some producers the opportunity to add their own little four minutes of 'creative input'... In short, the chances are that you'll have competition!

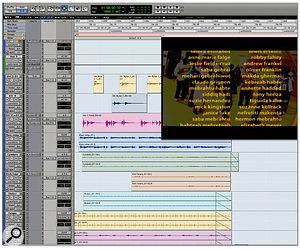

The finished Pro Tools arrangement for Dinka Diaries' closing credits, featuring percussion, bass, guitars and slide guitar. In the end, this piece provided much of the material for the rest of the score.This isn't the only problem you face. On TV, commercials or trailers for upcoming shows often begin almost as soon as the closing credits start to roll. The screen may shrink to make way for this information, and announcers often drown out virtually all sound. In the world of the cinema, people rapidly start to make their way to the exit, talking as they go. Is closing title music really worth the effort?

The finished Pro Tools arrangement for Dinka Diaries' closing credits, featuring percussion, bass, guitars and slide guitar. In the end, this piece provided much of the material for the rest of the score.This isn't the only problem you face. On TV, commercials or trailers for upcoming shows often begin almost as soon as the closing credits start to roll. The screen may shrink to make way for this information, and announcers often drown out virtually all sound. In the world of the cinema, people rapidly start to make their way to the exit, talking as they go. Is closing title music really worth the effort?

I come from the school of thought that believes that it's important for a film to have a consistent musical thread from beginning to end — and that includes the closing credits. Usually, when discussing music with directors, I'll ask about the kind of feeling he or she wants to leave people with as they exit the cinema. If the film is particularly tragic, do they want people to feel hopeful at the end, or devastated? Or will the music hint at a solution to a question that was left unanswered? In any event, the music at the end of the film can be just as important as the music scored at the beginning. It's up to you to make the case that your music would serve the picture better than the producer's nephew's (or ex-girlfriend's...) debut song.

I scored a short film once that contained some very difficult subject matter, and it had to be treated very delicately, with an intimate piano score supplemented with a gentle string orchestra. But once the credits began, a singer began to wail, drums crashed and guitarists flailed. This music was completely out of keeping with everything that had come before it. If you were so minded, you could argue that the film might have enjoyed greater success if the music during the credits had been a bit more sympathetic to the subject matter, and the established musical tone of the film. However, in this case, the director apparently felt humbled that someone had written this song 'just for the film' and couldn't resist. Once I heard the song over the end credits, I couldn't help wondering whether its composer had actually seen the film at all.

Assuming you do land the job of writing the music for the closing credits, you have an opportunity to wrap up the musical development of the film. Other than the difficulty of getting the job in the first place, the other main restriction is time. While the credits often run for over five minutes on large-scale blockbusters, I've often had to find a way to squeeze music into a minute or less. It's also fairly typical in my experience that the credits are not yet complete when I receive a 'final cut' of a film for scoring purposes, and whatever clients say when I ask them how long the credits will be, the number they give me is usually subject to change.

So how do you go about creating musical and dramatic closure for the end of a film? Let's answer this by example, and look at how I handled a few different situations.

As I was working on the music for Dinka Diaries, director Filmon Mebrahtu specifically requested an upbeat song for the closing credits. He wanted guitars and drums, similar in style to a recording made by Ali Farka Touré with Ry Cooder. He also wanted to include slide guitar in some way. And I somehow had to fit all of this into 30 seconds of screen time. What's more, I had to create a two-minute version of the same theme for use at public screenings of the film.

The first thing I did was search my drum loop libraries for some appropriate beats. Spectrasonics' Liquid Grooves library really came in handy for this. I recorded a few passes, using different combinations of percussion, and then edited what I had to work within 30 seconds. I added some snare and cymbals to complete my percussion track. Next, I turned to Spectrasonics' Trilogy bass instrument. I particularly like the sampled finger noises and squeaks of this instrument, as it adds to the realism of the samples. There are also a number of bass slides available, one of which I used in the introduction to my closing theme (these are far more effective than trying to use a mod wheel to simulate the effect).

Then it was the turn of the guitars. I'm not much of a slide guitar player, but I felt I could play a part sufficiently well if I planned it carefully. Using a Baby Taylor guitar, which is a great-sounding three-quarter-scale guitar, I retuned the strings so that the slide would play in the key of the song when playing across the top four strings. I used a Martin D28 acoustic for a second part, and then added a Gibson ES335 electric guitar plugged into a Roland Jazz Chorus amp. You can download an MP3 of the track at ![]() dinkacredits.mp3. Filmon was thrilled when he heard it, and liked it so much that the musical motifs I created here ended up being used as the basis for many of the transitional cues earlier in the film. These transitions were short cues of three to 15 seconds in length that were used on significant scene changes. So with a little 'reverse engineering', the theme for the closing credits became the source for much of the music appearing earlier in the film. In this way, by the time you got to the closing credits, it felt as if the music belonged there — which is usually exactly what you want to accomplish.

dinkacredits.mp3. Filmon was thrilled when he heard it, and liked it so much that the musical motifs I created here ended up being used as the basis for many of the transitional cues earlier in the film. These transitions were short cues of three to 15 seconds in length that were used on significant scene changes. So with a little 'reverse engineering', the theme for the closing credits became the source for much of the music appearing earlier in the film. In this way, by the time you got to the closing credits, it felt as if the music belonged there — which is usually exactly what you want to accomplish.

Relief & Release

A completely different example is provided by a short film that I worked on with Laura Storm, the director of The Narrow Gate (the film discussed in parts 7 and 8 of this series). As I mentioned previously, I was engaged solely to do sound design and mixing on this short, which preceded The Narrow Gate. Subsequently, I was asked also to score two short guitar-based cues. The film, All Souls Day, is a beautiful, sentimental story of a mother (played by Narrow Gate producer and lead actress Heather MacAllister) who has to come to terms with the death of her six-year-old daughter. The music for the film is primarily classical piano, and the ending is particularly moving, with the sustaining piano ringing out. But there wasn't any music for the closing credits. I spoke with the director about it, and suggested that something had come to mind which I would like to score. The budget had already been agreed, and there was no money left for additional music — but I felt so strongly about it that I did it anyway. Of course, this goes against what I've said earlier in this series about compensation, but what I did felt right at the time, and anyway, looking back, you'd have to say that I made a wise choice — within six months of this, I was hired to score The Narrow Gate, Laura's next film, which more than made up for the extra effort I put in on All Souls Day.

A promotional poster (top) for All Souls Day, Laura Storm's film about a mother (played by Heather MacAllister) coping with the loss of her daughter Alice (played by Taylor Spreitler, pictured above).For the closing credits to All Souls Day, I had just over a minute to work with. Laura and I had discussed the idea of using the music to create some 'closure', as well as a sense of hope. Without the music, you were left with a tear in your eye at the end of the film. With the music, the hope was that we'd add a smile in addition to the tear. The music I had in mind was very simple, with a clarinet playing the melody accompanied by a string orchestra. Once again, VSL's Opus 1 library provided all of the necessary ingredients. Working with Pro Tools, I used one instance of NI's Kontakt loaded with the necessary samples. Composing can be a long and arduous process, and sometimes you try many different approaches before you find the right one. However, this particular track flowed smoothly, and was finished in just a few short hours (you can hear the finished track at

A promotional poster (top) for All Souls Day, Laura Storm's film about a mother (played by Heather MacAllister) coping with the loss of her daughter Alice (played by Taylor Spreitler, pictured above).For the closing credits to All Souls Day, I had just over a minute to work with. Laura and I had discussed the idea of using the music to create some 'closure', as well as a sense of hope. Without the music, you were left with a tear in your eye at the end of the film. With the music, the hope was that we'd add a smile in addition to the tear. The music I had in mind was very simple, with a clarinet playing the melody accompanied by a string orchestra. Once again, VSL's Opus 1 library provided all of the necessary ingredients. Working with Pro Tools, I used one instance of NI's Kontakt loaded with the necessary samples. Composing can be a long and arduous process, and sometimes you try many different approaches before you find the right one. However, this particular track flowed smoothly, and was finished in just a few short hours (you can hear the finished track at ![]() soulscredits.mp3. Laura was extremely pleased, I was gratified with the result, and I got another gig out of it. A 'win-win' situation!

soulscredits.mp3. Laura was extremely pleased, I was gratified with the result, and I got another gig out of it. A 'win-win' situation!

It's certainly worth the time you spend persuading your employer to let you score the closing credits to their work. There are no hard and fast rules, and you can't guarantee that people will listen as the credits roll, but it's an opportunity to make a musical contribution to the film that can really count.

Be Seeing You

Hilgrove Kenrick and I hope that we've given you the essentials needed to tackle a career in making music for picture. There are entire areas of possible employment that we've barely touched on at all, such as music for video games and corporate presentations, although these have been covered in other SOS articles over the years (for examples, see www.soundonsound.com/sos/ nov01/articles/smartdog1101.asp and www.soundonsound.com/sos/ nov01/articles/corpvideomusic.asp, both from the November 2001 issue). You have to find the opportunities, as it is unlikely that they will find you. If you have the right tools, skills, and plenty of determination (plus a reasonably thick skin), you're probably ready to try your hand at writing music for picture commercially. Remember, there is no single way to succeed. These strategies are based on what has worked for us; you'll need to find your own way. What's more, you must remember that music is subjective, and that what works for one person may not work for another. All clients have different musical tastes, and it's rare that two composers will approach a scene in exactly the same way. The world is full of people with opinions about music, but in the end, there's just one that you need to please — your employer. As long as you keep that in focus, there's every possibility that you can make a living from music for picture like we do.