This month we follow the mastering process for Spektakulatius’s albums 10 and Sommeredition 2015, as carried out by Ian Shepherd at Mastering Media.

This month we follow the mastering process for Spektakulatius’s albums 10 and Sommeredition 2015, as carried out by Ian Shepherd at Mastering Media.

Spektakulatius: With last month’s mixes in the bag, our engineer was tasked with finding and working with a mastering engineer to put the finishing touches to both albums.

In June 2015’s ‘Session Notes’ (http://sosm.ag/jun15-session-notes), I wrote about a high–speed on–location tracking session I did for the German band Spektakulatius (www.spektakulatius.de), recording 28 songs across a wide variety of musical styles in less than five days. Then, in last month’s ‘Mix Rescue’ column (http://sosm.ag/jul15-mixrescue), I documented my mixing approach for this same production. This month I’d like to follow that up by showing how the mixes were brought together at the mastering stage to create a pair of finished albums.

Once I’d completed the mixes, the band asked me whether I could handle the mastering too, but this wasn’t something I felt I could say ‘yes’ to with a clear conscience. Like a lot of studio owners, I’ve learnt plenty about mastering over the years, but the main lesson has been that I’m no mastering engineer! So I recommended a few well–respected UK mastering engineers, from which shortlist the band chose Ian Shepherd at Mastering Media (www.mastering-media.com), asking me to liaise with him directly, both to surmount the German–English language barrier and to help get the quickest turnaround.

In my view, the advantages of professional mastering are frequently misunderstood by project–studio users, who often primarily seem to expect it to ‘finish’ or repair their mixes for them! This fundamentally isn’t the job of a mastering engineer, though — and there are many other important reasons for having an album mastered professionally, even when you’re already content with how your mixes sound, as the band and I were in this instance.

Fresh Ears

The first big benefit of bringing in an external specialist at the mastering stage is that they can approach the project with greater objectivity than anyone who’s been more deeply involved in the project’s gestation. As Ian himself put it when I interviewed him about his work, post–completion: “When you’re mixing and recording, it’s so hard to distance yourself. It’s tempting to use your ‘inside knowledge’ about why everything sounds the way it does to justify what you’re hearing and avoid changes that might be needed or beneficial. That’s why having somebody who knows none of the history of the project and just comes in and listens to it with fresh ears is really valuable. The whole thing about mastering is looking at the project as a whole in a relatively short space of time, so you can bring the ‘If I was the first person ever to listen to this, how would I react?’ perspective to it.”

To give a specific example, when I sent Ian the songs for the first album, he immediately suggested that I adjust the flute sound on one of the mixes. Sure enough, revisiting the mix in question I couldn’t help but agree with him — I’d been over–zealous with my high–pass filtering on that channel and the mix clearly improved when I eased off a bit. How had I missed this? Quite simply, I was too preoccupied with how the DI’ed electric–piano sound and acoustically isolated flute were blending with the live drums and bass in that particular mix, rather than the flute timbre itself.

But a mastering engineer isn’t just performing some kind of ‘everyman listener’ role, because he/she also brings a weight of experience to the task that non–specialists can’t match. While most conscientious mix engineers do spend a certain amount of time comparing their mixes against commercial releases, this process is very much the mastering engineer’s stock in trade, so it stands to reason that mastering professionals tend to have better skills and tools for making such critical comparisons. In addition, mastering engineers typically deal with a far greater number and variety of projects than mix engineers do, and are usually better informed about how different media–delivery formats and end–user playback devices impact audio transmission, which means they’re better able to judge how your sonics will actually translate to your target listeners in the real world.

But a mastering engineer isn’t just performing some kind of ‘everyman listener’ role, because he/she also brings a weight of experience to the task that non–specialists can’t match. While most conscientious mix engineers do spend a certain amount of time comparing their mixes against commercial releases, this process is very much the mastering engineer’s stock in trade, so it stands to reason that mastering professionals tend to have better skills and tools for making such critical comparisons. In addition, mastering engineers typically deal with a far greater number and variety of projects than mix engineers do, and are usually better informed about how different media–delivery formats and end–user playback devices impact audio transmission, which means they’re better able to judge how your sonics will actually translate to your target listeners in the real world.

In this case, for instance, Ian’s verdict was that he could subtly widen the stereo image of many of the mixes. “All I did was boost up the Sides signal,” explained Ian. “The advantage is that it’s basically a non–destructive process, in the sense that if it ever gets summed to mono it won’t introduce any unwanted side–effects.” This move made a lot of sense to me, because increasing the Sides level tends to both widen and wetten a stereo mix, counterbalancing my own innate mixing biases — not only do I instinctively err on the side of caution in terms of stereo spread, but I also tend to prefer drier mixes in general. By the same token, I mix almost exclusively in project–studio environments, where the acoustics are never ideal for making low–frequency judgements, so I deliberately tend to keep the low end in my mixes fairly tightly controlled by default. With the support of more critical mastering–grade monitoring facilities, however, Ian could more confidently shift emphasis back towards the sub–100Hz region for quite a few of the songs.

A Sense Of Belonging

Another major area where mastering engineers really earn their keep is in making a collection of different mixes ‘belong’ together on an album. Although the tools mastering engineers use to achieve this are actually often quite straightforward, it’s such a specialised listening and processing task that there’s simply no substitute for experience here, and few non–professionals are ever able to devote enough time to developing the necessary skills.

Another major area where mastering engineers really earn their keep is in making a collection of different mixes ‘belong’ together on an album. Although the tools mastering engineers use to achieve this are actually often quite straightforward, it’s such a specialised listening and processing task that there’s simply no substitute for experience here, and few non–professionals are ever able to devote enough time to developing the necessary skills.

The first of Spektakulatius’s two albums was particularly challenging in this respect, because it was a collection of festive songs, spanning a wide variety of different musical genres. Despite everything being recorded and mixed by a single person, the mix style inevitably varied quite a lot to suit the different genres, so neighbouring tracks in the album playlist often required quite different EQ curves from Ian to get them sitting comfortably next to each other. However, even on the much more stylistically unified and organic–sounding second album, Ian was still able to improve the song–to–song transitions with carefully targeted EQ changes, despite my best efforts to maintain consistent sonics across the whole project during the mixing process. As I said before: I’m no mastering engineer!

Since I’d expressed an interest in this aspect of Ian’s contribution, he was kind enough to send me some screenshots of his mastering settings, which also showed some level automation at work during a few of the songs on the Christmas album. “One of the things I’ll sometimes do is compensate for the dynamics processing that’s going on,” he explained. “For instance, I ducked the vocal for a couple of lines during the first song on the album, because it was hitting the mastering compressor much too hard, and it just sounded wrong. It was obviously pumping, and not working. So I tried the manual ducking as an experiment and it sounded better.” Elsewhere inter–section contrasts were increased by introducing stepped volume changes, and a couple of very subtle level ramps were added to assist with the inter–song transitions. “It’s unusual for me to do ramps like that,” he commented. “Usually I’ll do it in sections and go ‘OK, at this point it’s going to step up’. But with those songs I felt that wasn’t appropriate — the change needed to happen quietly, without anybody actually noticing.”

Mastering Dialogue

Some project–studio users seem to labour under the misconception that mastering is a kind of one–way street, and that the client’s contribution amounts to no more than sending the engineer the files and paying the bill. Ian says, “I have people come to me who’ve just uploaded their stuff to an online mastering house without anyone talking to anybody, made their credit–card payment, and got stuff back that they’ve hated. But then they haven’t even told the mastering house they’re unhappy, and that to me is crazy! Even if you can’t attend the session, which is more and more the case these days, any mastering engineer worth their salt will be open to hearing feedback.”

A constructive dialogue between client and mastering engineer throughout the mastering process can be tremendously beneficial for the final outcome, particularly in situations where the mixes can still be tweaked to order.

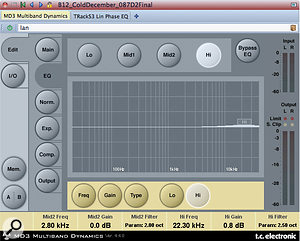

Here you can see Ian’s work in progress when mastering the second of the two albums.To illustrate what I mean, let me sketch out the workflow we followed for each album. First I discussed the nature and timescale of each project with Ian over the phone in very general terms. I explained that the band were already happy with the sounds of the mixes, so the main concern was making all the songs gel into a coherent album. Ian then checked over the files (immediately suggesting that flute mix tweak I mentioned above) and did a ‘test master’ of one of the songs so that we could discuss the overall sonic direction at the outset. I listened to the mix on a few different systems, and then emailed him to say that we were happy with his overall width, loudness and tonal decisions, on the whole, but also asked for a decibel less 2–3kHz, which made things feel a bit too hard–edged for me — this request was positively received and addressed.

Here you can see Ian’s work in progress when mastering the second of the two albums.To illustrate what I mean, let me sketch out the workflow we followed for each album. First I discussed the nature and timescale of each project with Ian over the phone in very general terms. I explained that the band were already happy with the sounds of the mixes, so the main concern was making all the songs gel into a coherent album. Ian then checked over the files (immediately suggesting that flute mix tweak I mentioned above) and did a ‘test master’ of one of the songs so that we could discuss the overall sonic direction at the outset. I listened to the mix on a few different systems, and then emailed him to say that we were happy with his overall width, loudness and tonal decisions, on the whole, but also asked for a decibel less 2–3kHz, which made things feel a bit too hard–edged for me — this request was positively received and addressed.

The next stage was a first draft of the full–album master, which again I listened to on a few different systems to build up a small list of desired revisions. While these requests were mostly just a decibel of level change or EQ here and there, or slight track–gap adjustments, some of them were actually much better dealt with by sending Ian updated mixes. For example:

- One slightly odd–sounding fade–out at the end of a song was better managed on an instrument–by–instrument basis with my mix–project channel faders.

- A low mid–range cut Ian had (justifiably) applied in response to the kick and electric–guitar sounds on one song had the side–effect of undesirably thinning the vocal tone. Applying similar EQ cuts with my kick and guitar mix processing allowed Ian to bypass that mastering EQ cut, reinstating the lost vocal warmth.

- By contrast, the vocal’s lower mid–range on another song seemed a bit congested to me once I heard it in the full–album context, but I didn’t want Ian to recess that spectral region overall with his master EQ, so it made more sense to apply some channel EQ to the vocal and rebounce the mix.

- One song in particular came across as too ambient in the first–draft master, a concern that would have been very difficult to remedy with mastering processing without knock–on effects for the mix’s sense of stereo width. Returning to the mix and nudging down the reverb returns, on the other hand, was a doddle.

What’s so great about this kind of give–and–take is that it enables both client and mastering engineer to do a better job than they’d otherwise have been able to. Ian’s mix feedback and draft masters meant that I refined my mixes to better suit their final context; and my feedback responses and revised mix files enabled Ian to reach a final master more quickly and with fewer processing side–effects. “If you want to get the best out of the mastering engineer, the key is communication,” remarks Ian. “It’s much easier — and more fun! — when a client talks to you.”

These screenshots show Ian’s mastering EQ settings for a selection of tracks from the more challenging project, the Christmas album 10. Notice how the settings are quite different from each other, a reflection of the wide divergence in musical genre and mixing style between songs.However, this can only really happen if you’ve left sufficient time for mastering. “It’s very common for people to leave the mastering right up to the deadline,” says Ian, “so there’s no time to go back and make any mix alterations. I always recommend that people allow at least a week, preferably a couple of weeks, not because it takes that long to master an album, but because you’ve got to get the files sent, I’ve got to fit it into my schedule, you’ve got to have time to listen to my draft and form a proper opinion, and if there’s a tweak or two needed, then we still have time to do it.”

These screenshots show Ian’s mastering EQ settings for a selection of tracks from the more challenging project, the Christmas album 10. Notice how the settings are quite different from each other, a reflection of the wide divergence in musical genre and mixing style between songs.However, this can only really happen if you’ve left sufficient time for mastering. “It’s very common for people to leave the mastering right up to the deadline,” says Ian, “so there’s no time to go back and make any mix alterations. I always recommend that people allow at least a week, preferably a couple of weeks, not because it takes that long to master an album, but because you’ve got to get the files sent, I’ve got to fit it into my schedule, you’ve got to have time to listen to my draft and form a proper opinion, and if there’s a tweak or two needed, then we still have time to do it.”

Spektakular Sound

When you’re producing music on a budget, the investment required for professional mastering isn’t something to be taken lightly. So if you do decide to bring in a specialist — and I hope this has highlighted many of the benefits of this — the best way to make sure you get your money’s worth is by treating the process as a collaboration, maintaining a positive cycle of feedback and adjustment on both sides of the relationship.

Listen Like A Punter

If you record your own music, it’s tempting to approach evaluating the first full draft of a professional mastering job in the same way you might evaluate a mix, methodically scrutinising each element of each song with the help of software tools, and referencing everything against multiple commercial references. However, I think that’s usually a mistake. By all means do this with a single–track test master to validate the engineer’s processing approach before proceeding with the whole album (as we did here), but once you’re listening to the first full–length master, it’s important to try to dissociate yourself from the mechanics of the production process and try to listen more as an ordinary punter would.

If you record your own music, it’s tempting to approach evaluating the first full draft of a professional mastering job in the same way you might evaluate a mix, methodically scrutinising each element of each song with the help of software tools, and referencing everything against multiple commercial references. However, I think that’s usually a mistake. By all means do this with a single–track test master to validate the engineer’s processing approach before proceeding with the whole album (as we did here), but once you’re listening to the first full–length master, it’s important to try to dissociate yourself from the mechanics of the production process and try to listen more as an ordinary punter would.

For a start, think about how your target audience consumes music day–to–day, and try to judge the album in those kinds of contexts. For the Spektakulatius project, for instance, I listened to the master not only on my studio speakers, but also on hi–fi headphones, a little stereo boombox, some PC multimedia speakers and my car stereo before signing off on my own revisions list. Of course, there’s no end to the possible playback alternatives, so you have to make a few judgement calls to make best use of time — so I didn’t bother checking this particular project on an iPhone speaker or club PA, for example, however relevant those devices might be for more mainstream chart styles.

Here’s another trick: funnily enough, it really helps me break out of the mixing engineer’s mindset if I actively concentrate on a song’s lyrics, because that usually prevents me focusing unduly on sonic technicalities that non–specialist listeners simply don’t notice in any conscious way. I also recommend playing the record top–to–tail rather than skipping through the tracks, not only because that gives a better perspective on the effectiveness of song–to–song transitions, but also because it encourages you to engage more with the emotional content of the music, as the public generally will. The more you start playing small snippets out of context, the more you’re likely to start obsessing about small sonic details at the expense of the big picture.

Here’s another trick: funnily enough, it really helps me break out of the mixing engineer’s mindset if I actively concentrate on a song’s lyrics, because that usually prevents me focusing unduly on sonic technicalities that non–specialist listeners simply don’t notice in any conscious way. I also recommend playing the record top–to–tail rather than skipping through the tracks, not only because that gives a better perspective on the effectiveness of song–to–song transitions, but also because it encourages you to engage more with the emotional content of the music, as the public generally will. The more you start playing small snippets out of context, the more you’re likely to start obsessing about small sonic details at the expense of the big picture.

Uncommon Knowledge

The moment at which I was most glad I’d resisted the temptation to try mastering this project myself came when the band added, almost as an afterthought, that they’d like to put a couple of videos on the CD too. While I’d probably have been able to cobble together a mixed–format disc like that somehow (with a bit of research!), the conversation I subsequently had with Ian about this highlighted once again the value of being able to draw on specialist experience. Not only was he able to explain the options for doing this in technical terms but was also able to advise, based on first–hand experience, how auditioning and manufacturing requirements would impact on both the delivery schedule and cost. On top of that, he also brought up the more general question of what the band wanted to achieve with their video content, pointing out quite reasonably that the proposed videos would probably do them more good as web publicity material, or as bonus content for mailing–list subscribers, than it would as an on–disc extra — an argument that eventually prevailed.

Audio Examples

On the SOS web site’s accompanying media page you’ll find a selection of before–and–after audio examples demonstrating how the sound of a couple of the tracks developed through the interactive mastering and remixing process described in this article.