Mix engineer Tom Elmhirst massaged the '60s soul vibe of the recording to create a radio-friendly hit in 'Rehab'.

Mix engineer Tom Elmhirst massaged the '60s soul vibe of the recording to create a radio-friendly hit in 'Rehab'.

For her second album, Back To Black, Amy Winehouse and producer Mark Ronson crafted a heavily retro sound. Mix engineer Tom Elmhirst describes how he massaged their '60s soul vibe to create a radio-friendly hit in 'Rehab'.

"Mixing is something that you either have, or you don't," muses British star mixer Tom Elmhirst. "You can learn the techniques, but after that you have to feel it. I don't think it's something that you can study. Music and mixing are so arbitrary in that sense. I enjoy mixing most when I stop thinking about what I'm doing. It's like when you're a kid, and you learn to ride a bike. Once you can do it, you don't think about the method any more. This is exactly how I approach mixing. I just do it, and if it feels good, I go with it. Sometimes I glance at my settings and think 'Oh, that's quite drastic', or I look back and wonder 'Did I really do that?' But if what's coming out of the speakers sounds OK, I'm not bothered."

This approach to mixing appears to work well for Elmhirst, who began his studio career at SARM Studios in London in 1992, where he quickly rose through the ranks to become engineer for the legendary Trevor Horn. He went independent in 1998, and his breakthrough as a mixer came with his work on Bush's Science Of Things (1999). His mix resume of the last six years includes Goldfrapp, Lily Allen, Moby, Roeyksopp, Paolo Nutini, Hot Chip, Sugababes and Kylie Minogue. Elmhirst has described himself as "not a very technical engineer". He says that he's increasingly economical with effects, prefers tightly organised edit windows that fit on the screen so he doesn't have to scroll, and doesn't care too much whether he's working at 8-bit or 96-bit, provided that the music is good.

Writer and vocalist: Amy Winehouse."Well, obviously I care deeply about sound quality," he says. "I will convert every project that's given to me to 96k, so at least when I print the mix back in, it's the best quality it can be. But it's true that I'm far more interested in the musical than the technical side of things. I've heard great multitracks that were 16-bit and terrible multitracks that were 24/96. At the same time, if you have 100 or more tracks running at 96k your computer just crawls along, so I will edit the amount of tracks down enough to be able to get them onto one screen. It's about manoeuvrability. I recently received a multitrack with 120 tracks, and I just can't mix with that. There's too much information. So if there are eight tracks of backing vocals, I'll bounce them to a stereo track. I don't really want to use the [Pro Tools] Mix window, I use the Edit page, and I want to bring everything down to a size that's workable for me.

Writer and vocalist: Amy Winehouse."Well, obviously I care deeply about sound quality," he says. "I will convert every project that's given to me to 96k, so at least when I print the mix back in, it's the best quality it can be. But it's true that I'm far more interested in the musical than the technical side of things. I've heard great multitracks that were 16-bit and terrible multitracks that were 24/96. At the same time, if you have 100 or more tracks running at 96k your computer just crawls along, so I will edit the amount of tracks down enough to be able to get them onto one screen. It's about manoeuvrability. I recently received a multitrack with 120 tracks, and I just can't mix with that. There's too much information. So if there are eight tracks of backing vocals, I'll bounce them to a stereo track. I don't really want to use the [Pro Tools] Mix window, I use the Edit page, and I want to bring everything down to a size that's workable for me.

"When I begin working on a multitrack, there's a period of two to three hours during which I familiarise myself with the song and see what's there. I'll have the monitors up loud to get into it and I'll clean up tracks, get rid of unwanted noise, do comps... whatever it takes so that by the time I connect Pro Tools to the Neve, I'll have everything down to one screen of the Edit window. I try to organise things such that all parts come up on the board in a familiar way, but most of all this whole process is about a head space. By the time I start the mix proper, I have the whole multitrack in my head and I know exactly what I want to do, what my vision is for the mix. After that it's a case of just getting it done. I'm listening pretty quietly and just working to get things right.

"Once I have an idea of how I want the song to sound, I'll just go for it. I will get a balance going, and will tend to work pretty randomly. I don't just solo the drums and get them right first or something. Instead I'll jump from getting the vocals sounding right back to the guitar, then work on the panning. Whatever grabs my attention. I'll be soloing various instruments, often applying hard notch EQ. I try to find things that I hate, and the way I do that is by adding specks of EQ with a high Q setting, find what I don't like and off it goes. I'm constantly moving like that. A lot of the time I'll be listening instrumentally, and every so often I put the vocals back in to make sure it is all working together. It takes time, but it all comes together in the end." Tom Elmhirst prefers not to use the Pro Tools Mix window, and pre-mixes Sessions to make everything fit on a single Edit window screen (see key overleaf).

Tom Elmhirst prefers not to use the Pro Tools Mix window, and pre-mixes Sessions to make everything fit on a single Edit window screen (see key overleaf).

'Rehab'

- Writer: Amy Winehouse

- Producers: Amy Winehouse, Mark Ronson

Tom Elmhirst: "'Rehab' was not the first song I mixed off Amy's album [Back To Black, which has so far gone 3x platinum in the UK]. I think that was the second single, 'You Know I'm No Good'. When I received Mark's original mixes, they were much more radical in terms of panning, kind of Beatlesque. The drums, for instance, were all panned to one side. I tried to mix one track, 'Love Is A Losing Game', in a similar way, but it just didn't feel right. The bulk of the recordings for the songs that Mark produced on the album were done at the studio of this band called the Dap Kings, in Brooklyn, New York. They recorded drums, piano, guitar and bass all together in one room. The drums were recorded with one microphone, and there's lots of spill between the instruments, which was great.

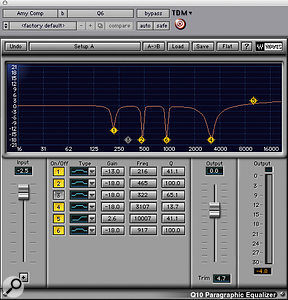

"When I first received the multitrack of 'Rehab' it was very small, with maybe only 20 tracks, but Mark then came to London to record strings, brass and percussion in one of Metropolis's tracking rooms. By the time all this was added, there were quite a few tracks, and I bounced a number of things -- backing vocals went from 12 to three tracks, for instance. The track has a retro, '60s soul, R&B feel, which is what the Dap Kings specialise in. It is definitely a nod to '60s soul wall-of-sound style production. For me, the mix had to have a contemporary feel to it as well, while Mark wanted to keep the mix sparse and not over-produced. I love Amy's voice and the vibe of the track, so mixing was a matter of getting the feeling right, with the brass, strings and percussion, but also getting it up to date beat-wise, so that it would work for radio without losing any of its charm. Although there's quite a lot going on in these tracks, they hopefully don't sound ridiculously complicated. The mix came together quite quickly, because I knew exactly what I wanted to do." As well as plenty of hardware processing, Amy Winehouse's lead vocal was treated with surgical EQ from Waves' Q10.

As well as plenty of hardware processing, Amy Winehouse's lead vocal was treated with surgical EQ from Waves' Q10.

Lead vocals

- Urei 1176 blackface compressor, Pultec EQ, Fairchild compressor/limiter, McDSP F2 Filterbank, Waves Q10 Paragraphic EQ, Waves De-esser, Great British Spring reverb, EMT plate reverb.

"I am not a techno snob, I'll use whatever I can to make a great record. Simple as that. I do try to keep compression and EQ analogue, unless it's EQ to notch out specific frequencies, in which case plug-ins are more precise and effective. Amy is a very dynamic singer. She has a lot of bite in her voice, but I wanted it to sound warm and not take your head off. I often use the Renaissance Q10 EQ for radical reductive EQ'ing, and you can see this in the settings I used on Amy's voice. I'm cutting four frequencies by 18dB; in two cases, 465 and 917, with a Q of 100! That's a really heavy notch. At 3107Hz the Q is only 13.7, so that's quite wide. Taking off 18dB here is enormous, but that's what it was.

Waves' De-esser was employed on Amy Winehouse's lead vocal to cut sibilance."There were specific frequencies in Amy's lead voice [the track labelled 'AmC'], that were bugging me. It may be due to hundreds of things, perhaps to do with the microphone that was used on the day. Don't get me wrong, it was not a bad vocal sound, but she does have some hard frequencies in her voice. There are a few tracks on the album that I did not mix [instead they were mixed by Gary 'G Major' Noble], and you can hear on them what she sounds like without the EQ I applied. I also use McDSP's Filterbank F2, probably shelving around 40Hz, and the Waves De-esser cuts around 5506Hz. Amy is not hugely sibilant. The threshold here is 22, which is not that high for me. There would probably be no more than 3dB of de-essing.

Waves' De-esser was employed on Amy Winehouse's lead vocal to cut sibilance."There were specific frequencies in Amy's lead voice [the track labelled 'AmC'], that were bugging me. It may be due to hundreds of things, perhaps to do with the microphone that was used on the day. Don't get me wrong, it was not a bad vocal sound, but she does have some hard frequencies in her voice. There are a few tracks on the album that I did not mix [instead they were mixed by Gary 'G Major' Noble], and you can hear on them what she sounds like without the EQ I applied. I also use McDSP's Filterbank F2, probably shelving around 40Hz, and the Waves De-esser cuts around 5506Hz. Amy is not hugely sibilant. The threshold here is 22, which is not that high for me. There would probably be no more than 3dB of de-essing.

"In addition, I was also filtering with a Pultec outboard EQ and on the board as well. The outboard chain on Amy's vocal was Pultec, going into a Urei 1176 blackface compressor, going into a Fairchild compressor. On the Pultec I was probably adding around 12k, just to brighten it up a little bit, adding air. The Urei will have been set with a very fast attack and a super-fast release, doing perhaps 10dB of compression, while the Fairchild will have had a very slow release. I can't quite explain what this does, but in my head the Urei will catch anything that jumps out, while the Fairchild will pick up the slack and keep a more constant hold of the vocal -- ie. smooth things out. During the mix I'll be constantly playing with these two compressors; it's not something I set up and then leave. How hard the signal coming from the Urei hits the Fairchild affects the sound a lot.

Trillium Lane Labs' Space convolution reverb was used to add a spring reverb effect."The vocals had a spring reverb which would have been tracked when they recorded Amy, at Chung King Studios in New York. I also recorded an EMT plate on the vocals at Metropolis. You can see both at the bottom of the Edit screen. I spent a lot of time on the vocal, and I would regularly come back to it. Late in the evening of the first day of mixing 'Rehab' I would have the vocal pretty much in the track all the time, and after that I'd constantly be tweaking it a little bit. I don't just do it and leave it. You're getting constantly closer to the final mix, but it's not immediate."

Trillium Lane Labs' Space convolution reverb was used to add a spring reverb effect."The vocals had a spring reverb which would have been tracked when they recorded Amy, at Chung King Studios in New York. I also recorded an EMT plate on the vocals at Metropolis. You can see both at the bottom of the Edit screen. I spent a lot of time on the vocal, and I would regularly come back to it. Late in the evening of the first day of mixing 'Rehab' I would have the vocal pretty much in the track all the time, and after that I'd constantly be tweaking it a little bit. I don't just do it and leave it. You're getting constantly closer to the final mix, but it's not immediate."

Drums

- Neve 33609 compressor, Waves Q4 Paragraphic Equaliser, Empirical Labs Distressor, Fairchild compressor, spring reverb

"I loved having the drums on one mono track, because there are no radical choices to make and you get the backing track balanced quickly, but I did spend quite a long time adding bass drums and snare samples [on the tracks called 'Ilk1', 'B11' and 'SRKc'] using Sound Replacer. I use the 'B11' bass drum sound in many of my mixes, it's a sound I put together. There's only so much you can do with one drum track, but I would have brightened it up to get as much of the snare on the track as possible. I did not worry too much about the low end, because I knew that would come from the samples. I also had to make sure that the mid-range was clear, because there's a lot of brass on the track, which almost plays the rhythm as well. So a lot of EQ'ing is about creating space.

"All the drums were on a subgroup that went to bus 3 and 4 on the Neve, which went to a Neve 33609 compressor and a Prism EQ. I also used one side of a Fairchild on the original drums as an insert. Some things, like the samples, did not go to bus 3 and 4, which is why I had two bass-drum samples. One bassdrum sample went to bus 3 and 4, and B11 went to bus 1 and 2, the main mix bus. So I could hit the Neve compressor pretty hard, with a very quick release, keep B11 clean, and balance the two bassdrum sounds.

Digidesign's Smack compressor was used to add drive to the bass track during the chorus only."The Waves Q4 EQ was about taking out unwanted spikes. This is exactly the same principle as with the Q10 used on Amy's voice. With one drum track you have little flexibility, and you can see that the Q's on the Q4 are all at maximum. I'm cutting at 155, 218 and 423Hz. These frequencies are really close together, and you'd be amazed what the track would sound like without them. 423 is the lower end of the snare, it probably had a honk in it.

Digidesign's Smack compressor was used to add drive to the bass track during the chorus only."The Waves Q4 EQ was about taking out unwanted spikes. This is exactly the same principle as with the Q10 used on Amy's voice. With one drum track you have little flexibility, and you can see that the Q's on the Q4 are all at maximum. I'm cutting at 155, 218 and 423Hz. These frequencies are really close together, and you'd be amazed what the track would sound like without them. 423 is the lower end of the snare, it probably had a honk in it.

"I also used a Distressor, which has a nice setting called British Mode, which gives you real bite. It's not a matter of nuking or slamming the drums with the Distressor, and again similar to Amy's vocals, I sent this to a Fairchild, which just glues it together. Apart from the spring reverb, which I recorded back in [to the track called 'rhsR'], there were no other effects on the drums. I had the drum spring on a separate fader and was riding it. You can hear on the track that the drum track is dryer in the verses, while the reverb comes right up in the chorus and the bridge. There are a lot of spring reverbs on this track, which contributes to the retro feel. I'm not a big fan of digital reverbs anyway. Some of the spring reverbs would have been recorded at the Dap Kings' studio, and some I added here in London."

Bass

- Urei 1176 blackface, Digidesign Smack!

"Most of my bass stuff has Urei compression, 4:1 and 8:1 ratios pressed in together, attack and release would be at three or five, not super-fast. Mark Ronson would have added the Smack! plug-in, and I love it. It's like another version of the Alan Smart C2/SSL compressor, if you like. The idea of the Smack! is to give it a slight vintage effect. It's not doing heavy stuff in this track, the bass was already pretty constant. It has a pretty fast release, of 2. The bass [track 'B02'] has a plectrum-like sound, and you want to keep that. You don't want to kill the attacks too much. I only used this effect in the chorus of the song; I thought it would give it a little bit more drive."  The piano had lots of spill from other tracks, which was partly cleared by cutting low frequencies with Sony's Oxford EQ.

The piano had lots of spill from other tracks, which was partly cleared by cutting low frequencies with Sony's Oxford EQ.

Piano

- Sony Oxford EQ, TLL TL Space, Waves L1 Ultramaximiser, McDSP F2 Filterbank

"The piano [track 'P02'] was recorded completely dry, but with a lot of spill from the drums and the bass. There's so much spill that I would have shelved everything under 500Hz, using the desk. It has a nice constant rhythm in the high end, and I needed to find a place for that in the mix. To my ears it was all about the mid to high-frequency ranges. The Oxford cuts below 100Hz and boosts a little around 5k. There's also an L1 limiter, and a Filterbank, which I use quite a lot, though only to filter the high end or low end. The reverb on the piano is from the Trillium Lane Labs [convolution reverb] plug-in, a vintage spring type. I put it as an insert on the track, rather than have it as an aux, so the 'dry' fader is set to 0, and I'm adjusting the 'wet' fader on the left."  To help fit the timpani into the track, Elmhirst limited heavily with Waves' L1.

To help fit the timpani into the track, Elmhirst limited heavily with Waves' L1.

Timpani

- Waves L1, Digidesign Lo-Fi, Waves Renaissance EQ

"Timpanis have a very hard attack and then lots of rumble. I wanted to get rid of some of the attack, because I had the drums doing that, and then have a nice smooth sustain. I may have tailed off the sustain on the board by riding the fader. At the same time you want to hear the timps, so it's a real balancing act. There's a lot of information below 300 to 400 Hz, but you're not going to hear that in the mix. I wanted to hear the high end of the timpanis, so I am cutting the low end and boosting around 1 to 3k with the Renaissance EQ, and then limiting heavily with the L1, keeping the release slow-ish. I also treated the timpanis with Digi's Lo-fi plug-in, to make it cut through a little bit more -- they also make plug-ins like Sci-fi, and there's Vari-fi, which I love; it slows things down and speeds them up.  Reducing the bit depth and sample rate with Digidesign's Lo-fi helped fit the timpani into the track.I changed the sample rate to 33k, which takes the top end off, and almost halved the bit-rate to 13, to break it up a bit. I'm not adding distortion, I'm just giving it a smaller, more concise frequency spectrum. It sounds weird on its own, but it works in the mix. As I said earlier on, it's not the technical side that matters, it's whether what comes out of the speakers sounds good."

Reducing the bit depth and sample rate with Digidesign's Lo-fi helped fit the timpani into the track.I changed the sample rate to 33k, which takes the top end off, and almost halved the bit-rate to 13, to break it up a bit. I'm not adding distortion, I'm just giving it a smaller, more concise frequency spectrum. It sounds weird on its own, but it works in the mix. As I said earlier on, it's not the technical side that matters, it's whether what comes out of the speakers sounds good."

Few would argue with that.

'Rehab' Edit Window Key

Reca: The mix, or recall master.

D03: The original mono drum track.

Rhsr: Drum spring reverb printed back in.

Ilk1: Bass-drum sample.

B11: Bass-drum sample.

Srkc: Snare sample.

Rhsp: Spring reverb.

145: Drum reverb.

T02: Timpanis.

B02: Bass.

C01: Bell.

Viba: Vibraphone.

Clap: Live handclaps (heavily edited).

Rhsp: Spring reverb.

W02: Wurlitzer, panned hard left.

Gtr: Guitar, not used.

102, 202, V02, Vc02: Strings.

Aux 1: TL Space plug-in spring reverb.

Bra: Brass.

T01-010: Brass.

AmC: Lead vocal.

Bv: Guess!

Sprn: Lead vocal spring reverb.

Plat: Lead vocal EMT plate reverb.

Mixing In The Digital Age

Tom Elmhirst began his career at a time when digital audio was already becoming mainstream, and witnessed the spectacular development of the medium close-up and first-hand. "Luckily for me, I started at the tail end of the analogue era and the beginning of the digital age," he recalls. "Eighty percent of the sessions I did at SARM in the early '90s were two-inch analogue, and I learned to count bars, drop in and be disciplined when track laying. Trevor's multitracks were always immaculate. You could push the faders up and let the tape run, and it would sound good. I know that was a way of working in those days, but it's an art that's disappeared a little in the computer era. People just lay things down, and in the end someone has to come in to make some decisions and sort it all out.

"When I worked with Trevor, our main format was pretty much the Sony 3348 [48-track digital tape recorder]. We also had Digidesign's Sound Designer, which was the beginning of Pro Tools, and which could only be used for two-track digital editing. There was no way you could use it as a stand-alone recorder. Pro Tools crashed all the time, it was a nightmare. I saw it going from twotrack to eight-track, to 24-track. I've worked with Pro Tools from the beginning, so it's not an alien format for me. I love what I can do with it."

Elmhirst's experiences at SARM and with Horn have clearly influenced his current working methods. It shows in his strong preference for working on analogue boards, particularly the Neve VR, and he acknowledges that his habit of submixing sprawling master files before beginning his 'proper' mix mirrors Chris Lord-Alge's habit of mixing Pro Tools files down to a 3348 (see May 2007's Inside Track). The main purpose for both mixers is to get to know, condense and organise the material they're given.

"What Lord-Alge does is exactly the same mentality," says Elmhirst, "but I just don't see the point of submixing to another format, so I premix back to Pro Tools. I prefer working on the Neve because of the headroom the desk has. Obviously I understand the fundamentals of mixing, so when I said that I'm not a technical mixer, I meant that I'm probably a little lax with things like headroom. When using an SSL, it would be probably overloading quite a bit, so I need the flexibility and headroom of the Neve. I don't like VCAs, and prefer Neve's Flying Faders, which essentially work with automatable volume pots -- the automation is very straightforward and simple. I can do tricks like panning and so on in the computer, while on the board I just want to be able to cut and to ride the faders. I find that over time I'm using less and less in terms of effects, and so working on the desk is all about balancing. Mixing in the box? Forget it, it's not for me at all. I'll sometimes mix in the box for stems, but I will always bring the full mix up on the board."