Andrew SchepsPhoto: Mix With The Masters

Andrew SchepsPhoto: Mix With The Masters

Under the guidance of producer Rick Rubin, Black Sabbath returned to their roots. Mixed by Andrew Scheps, the resulting album 13 topped charts worldwide.

Before the recording sessions for Black Sabbath's 13 began, producer Rick Rubin told singer Ozzy Osbourne, guitarist Tony Iommi and bassist Geezer Butler to revisit their first album. They were nonplussed, to say the least. In an interview with Spin magazine, Osbourne remarked, "I was like, 'What the fuck's the deal, man? Why the first album? We've all done a billion albums since then.' He goes, 'You're not a heavy metal band. The first one was a blues album.' I didn't know what the fuck he was on about. I thought he was fucking nuts. But I got the fucking punchline three weeks later. It wasn't that he wanted a blues album so much as he wanted the blues feel from us.”

"I had a similar conversation with Rick before mixing,” recalls Andrew Scheps. "He said to make sure I went back and listened to the first four records. I did, and immediately got it in terms of feel and balance, but also realised that, sonically, what we were going to do would have almost nothing to do with those records. As much as everybody says that the first Black Sabbath albums sound awesome, and they do, you could not put out a record like that now. They work because they're classic albums of their time, but it simply is not what records sound like today. If I had tried to mix their new album to make it sound like their first albums, nobody would have liked it. It would not make sense.”

Lucky Numbers

The sonic chasm that separates Black Sabbath's first four albums — their self-titled 1970 debut album, the same year's Paranoid, Master Of Reality (1971) and Black Sabbath Vol. 4 (1972) — from 13 encompasses most of the history of rock production. In the early '70s there were no digital tuners, no drum machines and no digital editing capacities, and occasional tuning issues and performance quirks such as speeding up or slowing down were par for the course. Since then, our ears have become accustomed to music that's perfectly in tune and in time. Moreover, today's productions typically have a much louder and denser sound, with more low and high end. Black Sabbath's first two albums were recorded cheaply and quickly on four-track tape recorders, whereas many of today's DAW sessions contain well over 100 tracks. All these dramatic changes don't even touch on the radical developments that have taken place in music itself.

The sonic chasm that separates Black Sabbath's first four albums — their self-titled 1970 debut album, the same year's Paranoid, Master Of Reality (1971) and Black Sabbath Vol. 4 (1972) — from 13 encompasses most of the history of rock production. In the early '70s there were no digital tuners, no drum machines and no digital editing capacities, and occasional tuning issues and performance quirks such as speeding up or slowing down were par for the course. Since then, our ears have become accustomed to music that's perfectly in tune and in time. Moreover, today's productions typically have a much louder and denser sound, with more low and high end. Black Sabbath's first two albums were recorded cheaply and quickly on four-track tape recorders, whereas many of today's DAW sessions contain well over 100 tracks. All these dramatic changes don't even touch on the radical developments that have taken place in music itself.

In this context, the Black Sabbath members understandably felt that Rubin's idea of going back to their roots was risky, given that there were 40 years to bridge in terms of aesthetics, working methods, technology and the like. However, given the overwhelmingly positive reviews that 13 has received, and the album's top position in many hit parades around the world, Rubin's strategy clearly created the desired results. It is widely judged to be a worthy successor of the early Black Sabbath albums and a welcome addition to the band's canon.

13 is the first Black Sabbath album featuring Osbourne since he was asked to leave the band in 1979, and the first under the band's name since the critically panned Forbidden (1995). The original line-up of Black Sabbath — Iommi, Osbourne, Butler and drummer Bill Ward — reunited for tours in 1997 and 1999, and began work on a new album in 2001, also with Rick Rubin, but that project was abandoned and Ward left the band. Several replacements were considered, until the company settled on Rubin's suggestion of Rage Against The Machine drummer Brad Wilk.

Analogue Workflow

Numerous interviews and several 'making of' videos have cast light on the writing and recording process, but so far, no attention has been given to the two-month mix process during which everything came together. From his Punkerpad West studio in Los Angeles, Andrew Scheps explains how he managed to retain and enhance the feel of those early '70s albums, while also making sure that 13 sounds up to date in 2013. The key, it seems, was working in the analogue domain. "When I was working with the Chili Peppers on Stadium Arcadium during 2005,” said Scheps, "they decided to record and mix it entirely on analogue and mix on a Neve. If you buy the vinyl version of that record, the signal chain will have been analogue all the way through, having been tracked to two-inch analogue tape, mixed through a Neve, printed to half-inch, mastered in analogue and cut directly to vinyl. My experience of working on that album informed my decision to buy a Neve 8068 console and to return to mixing outside the box. One aspect of that is the sound, but the main reason for me working in this way is that I love the workflow, the logistics of it. It is about having physical knobs in front of me for everything that always do the same thing, so I don't ever have to think about anything. I am a very physical, hands-on mixer, and I hate having to hunt for something. When I know what I want to do, I want to be able to just grab a knob and do it.

"Many of the same mistakes can be made in analogue and in digital, the only difference is that they're more easily made in the digital domain. Even with the crazy amount of gear I have here in my studio, I will at some stage run out of outboard to use, whereas it's very easy to be tempted into using an infinite amount of plug-ins. Part of the myth of digital not sounding good is that many people aren't very good engineers. On the other hand, digital is more forgiving. Analogue colours the hell out of the sound, and this can be an amazing thing, but you have to know what you're doing. You have to be aware of the gain structure, the noise floor, all these things that you don't really have to worry about the same way with digital. You can do what you want in digital, and record things badly, but it'll sound OK, until you run out of room.”

The Punkerpad West wall of outboard: Andrew Scheps' retirement fund!

The Punkerpad West wall of outboard: Andrew Scheps' retirement fund!

Andrew Scheps certainly has plenty of experience of working with digital audio. Growing up in New York, he studied recording at the University of Miami from 1984 to 1988, and after that went to work for New England Digital, who made the pioneering Synclavier digital sampling, synthesis and recording system. The Synclavier system was astronomically expensive, hard to operate and came with its own engineers. Scheps travelled for three years around the US and Europe as a Synclavier engineer, partaking in high-profile sessions with artists like Sting, Mark Knopfler and Benny Anderson. In the early '90s, he left the company, because he "wanted to make records” moved to Los Angeles and worked hard to get into the studio game as an engineer. Helped by his experience of these high-profile sessions, he was remarkably successful at this, quickly clocking up credits such as Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Robbie Robertson, Iggy Pop and U2, and teaming up with Rick Rubin for the first time in 2001, for Saul Williams' Amethyst Rock Star. As a mixer and/or engineer, Scheps has since worked on many of the high-profile projects Rubin has produced, including tracks by Jay-Z, Neil Diamond, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Linkin Park, Metallica and Adele, while also branching out into production. Scheps recently produced the new Gogol Bordello album Pura Vida Conspiracy, and also runs a small label called Tonequake.

Options Open

Arriving at the subject matter at hand, mixing Black Sabbath's 13, Scheps focused on the album's first single, the track 'God Is Dead?' to illustrate his approach. With its whopping 50 tracks of audio, the Pro Tools session screen shots later in this issue make it immediately obvious that this is a 21st Century project. Given that the ethos of the recordings was to track the band live in a room and keep overdubs to a minimum, one wonders how just three guys playing and one singing added up to that many tracks. Scheps wasn't present during tracking — basic tracks and some overdubs were recorded by Greg Fidelman at Rubin's Malibu studio, Shangri-La, while additional overdubs were done by Mike Exeter in England — but was nevertheless able to explain.

This composite screen capture shows all the audio and aux tracks in the Pro Tools session for 'God Is Dead?'.

This composite screen capture shows all the audio and aux tracks in the Pro Tools session for 'God Is Dead?'."The reason why the sessions were quite big was because they wanted to be able to quickly and easily jump from song to song while tracking. They'd work on two or three songs a day, and for this reason they had many different mics on the drums, the bass and the guitar. These would normally have been combined into fewer tracks, but instead all recordings were kept separate for maximum sonic flexibility. So 'God is Dead?' has 23 drum audio tracks, one bass part spread over five bass tracks, and three guitar parts, each spread over three tracks. There are also two solo tracks and four guitar sustain tracks just playing one note to smooth out the switch from a loud to a quieter section. So that's 15 guitar tracks. So the song, in fact, has very few elements: drums, bass, a distorted rhythm guitar and two clean guitars, and a couple of brief additional guitar overdubs. There also are a stereo piano part, just for low reinforcement stuff, two 'Zombie' tracks, which is a weird little sound effect made up by Tony on a keyboard, and finally two tracks of vocals. The session still contains 11 tracks of intro sound effects, which took me six hours to build, but we didn't use them.

"It wasn't like when they were doing the first Black Sabbath record, which was made in two days. This took quite a bit more time than that! But when you're working on a song and it's not quite coming together, the best thing is to just switch to working on another song. You can then later come back to the first thing, and when you record all amplifiers and drum mics individually and everything is always ready to go, you don't have to think about what amps and mics you were using for each song. Also, there are quite a few long songs, and if you only had one guitar tone you are tying your hands. In any mix, but particularly if a song is long and you have relatively few instruments to work with, you want to be able to really get inside of a guitar tone, and change it subtly from section to section. If I had not been able to do that using the source material, I would have ended up multing the guitar out on the console.”

Room To Develop

The mixing of 13 took place from late January to mid-March 2013, with 'God Is Dead?' being mixed on January 28, followed by a recall on March 7. There are only eight songs on the standard version of the album, with an additional four bonus tracks for various special editions. Of the eight regular album tracks, five clock in at more than seven minutes, and 'God Is Dead?' is nearly nine minutes long. In a day when many producers tool their product especially for audiences with short attention spans, the luxurious way in which many of the riffs on 13 are introduced is a direct throwback to an earlier age. Scheps explained that, paradoxically, the fact that there were relatively few instruments for him to work with made mixing the longer tracks more time-consuming. It was one of several reasons why mixing took nearly two months.

Black Sabbath, 2013: from left, bassist Geezer Butler, singer Ozzy Osbourne and guitarist Tony Iommi.

Black Sabbath, 2013: from left, bassist Geezer Butler, singer Ozzy Osbourne and guitarist Tony Iommi.

"We worked on mixing the album the whole time,” said Scheps. "It was a long process, in part because we were in fact mixing 16 songs in total. Many of the songs were quite long, and it definitely is in some ways more difficult to mix an eight-minute-long song with just three tracks of guitar than if you had 15 and you have more colours to work with and the shifts in arrangements are more obvious. The performances were amazing, and it took a lot of work to accentuate the dynamics in them, without being over the top or too obvious. We also didn't want things just to sound big: they needed to sound huge. The basic tracks were recorded live in the studio, with only the vocal later being replaced, mostly because the lyrics were not finished yet. The rhythms and tempos are very tight, but people make the mistake of thinking that this means things were fixed. That does a disservice to these guys. They've been playing for 40 years, and what you hear on the album is the natural result of how they've developed over that time. One of the goals of this record was that we wanted to make sure that when you listen to the music, it sounds like a band playing. I think we managed that. It doesn't feel like there were a ton of overdubs and it doesn't feel very processed, it just feels like Black Sabbath.

"My biggest challenge in my mixes for 13, especially in the longer songs, was to maintain the feeling of the songs and to not lose the listener at any stage. A lot of that has to do with the balances and how they change over the course of a song, and this is where mixing out of the box is absolutely vital for me. My decisions are rarely based on anything other than how what comes out of the speakers feels. Sometimes the balances are surprising to me, and sometimes it's possible to go with that, and sometimes not, because someone may disagree. But these balances are not based on analysing what is louder than what. I could not care less about that. I really is just about what I am hearing, and feeling. I manually get a balance and find pan positions, and I am EQ'ing and doing all the things you do when mixing, and if it's not working, I pull all faders down again and start again from scratch. I might, this time, start with a different instrument, or exactly the same way. The balance gets built up like that, without me using automation. I'll do this multiple times until all of a sudden I get the feeling the song is playing itself. If you'd look at the faders for each of these balances they would have looked very similar, but if every fader is in a different spot by half a decibel across 32 faders, you have a very different mix.

"I break up the mix moves that I do into two categories. I do the structural moves to make a song work in Pro Tools, before I start mixing on the desk. These are the more drastic things that, if you don't do them, the song will fall apart. I will also already have done quite a lot of shaping and combining work in Pro Tools. For example, I'll submix the drums until they come up on maybe 10 faders on the desk. If a guitar part is spread over multiple tracks, they will definitely be combined, and so on. On my desk channels, 1-12 will usually be my drums and bass, with the kick on one and the snare on two, from 13 onwards will be the other musical instruments, and channel 24 will be the lead vocal. The vocal is almost in the middle of my console, next to the master section, the first fader of which will be the drum master drum group.”

Prep School

According to Scheps, combining and shaping the tracks in Pro Tools is part of his preparation work to get a session ready to mix on his desk. "The prep work is a big part of the mix. The half an hour to 45 minutes it takes me to colour-code the session — 'Everybody else uses the wrong colours!' — and assign outputs and decide what I'm going to combine and whatnot is also a discovery process, during which I get to know what's in the session and what's under every fader on my desk. It's a definite first step of the mixing process. The transport is always running while I'm setting up the session, so I'm listing to it the whole time. I'll listen to the rough a couple of times, and to individual tracks to decide where to place them, and if there are plug-ins, to hear what they do and decide whether to leave them in or not. I might also add my own plug-ins. If there's mix automation, I'll decide what I need and what I prefer to switch off. Greg's roughs for the Black Sabbath album were done on a console, so if there were plug-ins on the sessions, they usually were just one-band EQs, as a high-pass filter, or a specific effect that the band wanted and that they happened to do in the box. Overall, there were very few plug-ins in the sessions, which was great, because the recordings sounded like they wanted them to sound. I am a big fan of very simple rough mixes, because intricate rough mixes always end up being things that the mixer has to beat. Greg's mixes were nice and loud, but very simple.”

The down side of working in the analogue domain: recalls require extensive documentation!

The down side of working in the analogue domain: recalls require extensive documentation!

Only after having prepared the mix inside Pro Tools and laid it out over his desk does Scheps mix as if it's 1986, in a process that's all about feel and intuition. "Yeah, the desk moves are much more like doing front-of-house for a band playing live. They are the moves I do to make things more exciting. Because the order of the faders is always the same, and because I have set everything up so I can grab anything at any time I want, I can mix without having to look at anything or having to think about anything. I just do it. When you look at a screen you're second-guessing what your ears are telling you, which is why everybody needs the Massey Listen plug-in, which makes the screen go blank.

"If it is a rock track, I will usually start with the drums, because they have by far the most tracks to make up one instrument. My goal is to turn that instrument into one fader, which is my group fader, so I don't have to think any more about the 20-odd tracks that make up the drum kit. Once I've got the drums to play as one instrument, I will work left to right on the console — bass, guitars, keyboards, vocals, and to the right of the vocals will be extra stuff, percussion or sound effects — to get the basic tones and an overall balance. After that, I jump all over the place and it's a free-for-all. While making the mix moves, I will usually let the whole session run, also with the longer Black Sabbath songs, and I'll start to hear what I need to do and make the moves manually, still with the automation off. In my head, I'm building up a list of all the moves that I need to do. I do these moves over and over again until I finally switch on the automation, and get all the moves inside of it. I can't stop during this process. I can keep the stuff in my head, but an hour later I'd have forgotten most of them. It really is a mental balancing act to keep all that in my head. The automation is only for the faders, so I also do quite a bit of automation on the effect return faders.”

Like many mix engineers, Andrew Scheps employs Avid's Lo-Fi plug-in to add grit where needed.

Like many mix engineers, Andrew Scheps employs Avid's Lo-Fi plug-in to add grit where needed.

Drums: desk EQ, Neve 2264, Dbx 160VU, RCA BA6A, Spectrasonics 610, Softube TSAR1, Waves L2, Chandler TG1, Avid Digirack EQIII & Lo-Fi.

"All the drum tracks are in purple, apart from a couple of floor-tom tracks in pink. The drum tracks are a little out of order in this session: the overheads and the toms are at the top of the session, probably because I was dragging things around to look at some timing stuff. Sometimes I will bounce stuff, and I'll then align them back up. For example, there's a track called 'Drums 2264', marked as 'GID Drums Bounce' in the regions, which are in black. I usually have my Neve 2264 compressor as my two-bus compressor on the console, but in this mix that just wasn't working. For whatever reason, it did not handle the song well, but the drums sounded great, so I sent a stereo mix of the drums through the 2264 and bounced that back into the mix. It came up under a couple of faders on the desk and ended up being a huge component of the drum sound. It acted like parallel compression. In addition to the 2264, there is quite a bit of outboard on the drums, and in fact the entire session. The recall notes run to 30 pages!

Obviously, I'm EQ'ing on almost every channel, on the board, and using outboard. I paid for these EQs, so I better use them! I had parallel compression on the drums and the snare, using the Dbx 160VU. Both the kick and the bass guitar are sent to a parallel RCA BA6A compressor, and the snare also goes to a parallel Spectrasonics 610 comp/limiter. Plus there's a little reverb on the snare from a Softube TSAR1 reverb as a send — the aux track is at the bottom of the session, and also has an L2 on it to bring up the level of the reverb. Having reverb is atypical for Rick's projects, because we usually keep things dry, but not putting some room around the snare sounded weird with Ozzy's voice. On the rest of the drum kit, like overheads and toms and things like that, I had a Chandler EMI TG1 compressor as a side-chain.

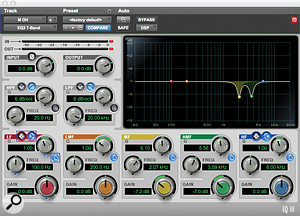

Relatively few plug-ins were used in the mix. Avid's Digirack EQIII was used to notch out a couple of problem frequencies in the drums.

Relatively few plug-ins were used in the mix. Avid's Digirack EQIII was used to notch out a couple of problem frequencies in the drums.

"There also are quite a few plug-ins on the drums. I had three instances of the Digirack EQ3 on the kick. On the 'Kick Out' track, it adds some low end, and the first one on the 'Kick d30' track underneath is a one-band low-pass filter that Greg had put in, and I then added a seven-band EQ with some crazy settings to get more low end. And then I didn't use it! Below that are mono faders for the kick and the snare, and I used the Lo-Fi on both of them, with just 0.2 distortion and everything else turned off. It was just to add some colour. I think that the Lo-Fi is an amazing plug-in when you just scratch the distortion. The 'Snare Top' track had an Expander/Gate that was put on by Greg, but I got rid of that because I felt that it made the hi-hat move too much, and the snare bottom has a seven-band EQ3. On the 'Ride' track is another EQ3, just taking out some low end. Below that is a master track for the overheads, dipping out 2.07kHz and 359kHz with the EQ3. When I use EQs in Pro Tools, it usually is for very surgical things, and this is a good example. Brad Wilk is an amazing drummer who plays really hard, and the cymbals were everywhere, so I notched out these two frequencies.”

Bass: RCA BA6A, SPL Transient Designer, UAD Helios EQ.

"They had two different amps, recorded with three mics, and two DI tracks. I didn't have a lot on the bass, because it just sounded amazing. In outboard there are two parallel compressors, one being the BA6A I mentioned above, which is shared with the kick drum, and also the vocals. Then I have a Transient Designer as a side-chain with the attack all the way turned down and the release up a little bit. It's a weird thing that I tried years ago, and that I like doing. It basically helps to even out the low end, so that no notes disappear or stick out. I can't stand riding the bass level to fix this, though if there is a real problem note in the recording I may fix it in Pro Tools with a quick volume ride or something like that. 'Master 7' is the master bass track, on which I used a UAD Helios EQ plug-in. When you just pop it to 60, it adds this amazing bloom to the low end. I also added a little bit of mid-range with it.”

The UAD Helios EQ was used to thicken up Geezer Butler's bass sound.

The UAD Helios EQ was used to thicken up Geezer Butler's bass sound.

Guitars: desk EQ, UAD Helios EQ, Alan Smart C2, SPL Vitalizer, Waves L2, Urei 1176.

"There were a couple of songs on the album, like 'Zeitgeist', on which I did some processing on the guitars, but for the most part I left them pretty much the way they sounded. There's very little EQ, because the guitars sounded great. I just used some desk EQ and some UAD Helios plug-in EQ, which has a really cool mid-range. I had parallel compression on the guitars from the Alan Smart C2, although on many of the other songs it was a Fairchild 670. The plug-ins on the main guitar part, consisting of three tracks, are mostly from me. There's a compressor that Greg put on, and I added an SPL Vitalizer, then a Helios EQ, and an L2 set to just 0.2dB, just to keep the clip lights off. This is the chain on both guitar tracks, and on the third track it's just the Helios and the compressor Greg put on. I added some mid-range to find the sweet spot where the notes were and bring them out a bit more. 'Master 6' combined these three guitar tracks, and again it has the Vitalizer and the L2. Below this are the four sustain tracks that help link the loud section with a quiet section, and then there are two sets of three clean guitar tracks, which were overdubs, and the master tracks again have the Vitalizer and the L2, used very sparsely. Finally there are the two solo tracks. Many of the solos were played by the tracking guitar, but in this case it was an overdub. There were two amps and they added a delay, which I kept. When a guitar player adds an effect, it's the sound he wants. On the rear bus of my Neve console, I also had a pair of Urei 1176s, as parallel, through which I sent everything apart from drums and bass. So the guitars, piano and vocals had some of that added in.”

Relatively few effects were employed on Ozzy Osbourne's voice, one of them being a simple delay.

Relatively few effects were employed on Ozzy Osbourne's voice, one of them being a simple delay.

Vocals: Waves Renaissance Vox, 1176, Aphex Vintage Aural Exciter & L2, Avid Trim & Slap Delay, Cranesong Phoenix, RCA BA6A.

"Ozzy's voice sounds insanely great with electric guitars and cymbals. It is incredible how it cuts through and how easy it is to hear him. There are just two vocal tracks: one lead vocal and one double that he overdubbed. The plug-ins are really simple, with a Waves Renaissance Vox and an 1176 that Greg had put on, and it just sounded good, so I didn't touch it. The double had the same plug-ins, plus a Trim and a short slap delay, again both added by Greg, and I again left them because it sounded good. If the vocal sounds great, I'm not going to reinvent the wheel! I did create an entirely separate audio track, placed in between the lead and the double, for delay repeats on certain phrases. Rather than automate a send on the main vocal track itself, I prefer to do this on a separate track by copying bits of audio. It's easier to put a fade-in on a small chunk of a line than to automate that. Secondly, the delays are in time, a quarter note in this case, and sometimes the word that gets sent to the delay is a little early or late, and suddenly your delay does not sound good. So in having these bits of audio on a separate track I can move them in time to make sure the delay is exactly in time.

"The master vocal track underneath these three tracks had a Waves Aphex Vintage Aural Exciter on it, just for some additional top end. There's also a Cranesong Phoenix saturation plug-in to add some colour, and again an L2, again set to 0.2 [ceiling]. Because I had two vocals, I did not want to have to bother with looking at the level. The outboard gear on the vocals was another Vintage Aphex, as well as the BA6A that I also had on the kick and bass.”

Waves' Aphex Vintage Aural Exciter was used to add extra 'air' to the vocal.

Waves' Aphex Vintage Aural Exciter was used to add extra 'air' to the vocal.

Master Bus: UAD Pultec, Waves Puigchild, Massey L2000, Neve 2264.

Scheps recorded the final mix back into the session, which was at 96kHz, 24-bit — the resolution Rubin and he use for all their sessions. "The 'Router' track takes the stereo inputs from the console and routes it to the stereo track on which I print the mix. I usually do two versions, one without anything, and one with some plug-ins for the listening copy that I send out to the band and the label. In that case, I put on a UAD Pultec plug-in, adding a bit of 100Hz, and I normally use a pair of Lang EQs on my mix bus, which are based on the Pultecs. I love them, but they don't have a lot of headroom, and because this mix was very loud I used the Pultec instead. I also had the Waves Puigchild plug-in on it, but it's not compressing at all, it's just for some coloration. Finally, there's the Massey L2000, again set to just 0.2dB. We did actually find that the song sounded slightly different to the other songs because it didn't have the Neve 2264 on the mixbus, so I did a recall just to run the mix through the 2264.”

Mastering for 13 was done by Stephen Marcussen and Stewart Whitmore. Scheps noted that he was "very involved” in the mastering process. "It was very interactive, with us going back and forth for weeks. It was great.”

13 has come in for criticism in some quarters for its allegedly over-compressed sound, criticism which Scheps rebuts. "The album is loud, but it is in line with what metal records sound like today. It is not distorted and it is not square-waved. You can really hear the individual guitar performances, and Tony's fingers on the strings, and the bass is very audible, which usually it isn't. Parallel compression brings up the VU level without messing with the peak level, so my mixes have a ton more loudness than they would if I did not use parallel compression. While mastering 13, Stephen [Marcussen] said that he was glad that my mixes are loud, because he gets many mixes that have a lot of limiting on them, and when he takes the limiting off, the waveform is like a fish skeleton. There's no level, but because it's what people have been listening to you can't get rid of the sound of the limiting. Loudness is not just about making things sound loud, it's also about what stuff sounds like when you go to the limit in the analogue domain, and about the way the gear handles the level, and the way in which digital converters handle the level. That's all part of the way modern records sound. My mixes are crazily loud coming off the consoles. When it comes to the choruses, the meters don't even move! They are pinned. I mix like that because it sounds good to me. I think that 13 sounds really good and I am very happy with how it turned out.”

Punkerpad West

Where possible, Andrew Scheps likes to work at his own LA studio, Punkerpad West. "I've had this room for 18 years now, and during the last 10 years it has grown into a place where I'm very comfortable. I know everything about this room, and it saves me many hours when I mix here, so I mix here unless I have to go somewhere else for logistical reasons. The room has some acoustic treatment, with rugs on the floor and hanging from the ceiling, and, being 22' by 25' with very high ceilings, it is pretty dead. It's almost like mixing outside. I don't really have any reflections to deal with, I'm just hearing the speakers, which are Tannoy SRM10Bs. I also have some Yamaha NS10s, with a sub, and for every single project, when the band comes in, during the first day we switch back and forth between the NS10s and the Tannoys, and they take the mix home and we never listen to the NS10s again. They are just there for other people as a reference. The Tannoys are pretty bright and definite-sounding and they are the only monitors I listen to. I never reference anything anywhere else, because I don't have to at this point.”

As well as an impressive collection of outboard, Punkerpad West boasts not one but two Neve 8086 desks.  Punkerpad West is based around two Neve 8068 mixers. This is the main one, through which all the source tracks pass."My Neve desks are from 1978 and 1979 and they are completely tied together, so it is, in effect, one 64-input console with Flying faders across all 64 faders. The console in front of me usually handles all the source material coming from Pro Tools and the other console is for effect returns and extraneous overdubs and so on. The reason I have them in an L-shape is that having one 13-foot-wide console does not make sense. You never sit between the speakers! Because of the way the consoles are situated, when I sit in front of my first console I can, at the same time, grab eight faders on the second console just to my left. I can reach every single fader without moving and remain in front of my speakers all the time.

Punkerpad West is based around two Neve 8068 mixers. This is the main one, through which all the source tracks pass."My Neve desks are from 1978 and 1979 and they are completely tied together, so it is, in effect, one 64-input console with Flying faders across all 64 faders. The console in front of me usually handles all the source material coming from Pro Tools and the other console is for effect returns and extraneous overdubs and so on. The reason I have them in an L-shape is that having one 13-foot-wide console does not make sense. You never sit between the speakers! Because of the way the consoles are situated, when I sit in front of my first console I can, at the same time, grab eight faders on the second console just to my left. I can reach every single fader without moving and remain in front of my speakers all the time.

"In addition, I have a Neve BCM10 sidecar, which I used for mixing before I bought the second 8068. The BCM10 is now only used for recording. Having the second desk is almost a necessity for me, because I rarely insert effects; most of what I do is parallel. I have probably about 20 channels of returns always patched into my second desk, including tons of compressors for parallel compression. This means that I only have to hit buttons on the consoles and the effects are there, and this relates to my visceral, hands-on approach to mixing that I mentioned earlier. I rarely go over to the computer to insert effects in that.”

While Scheps's towering collection of outboard is as eye-catching as it is mouth-watering, one does wonder how practical it is in this day and age of instant recalls, where mixers are often asked to perform small mix adjustments weeks and months after they mixed a track. He replies, with tongue firmly in cheek, "Yes, it's true, when people ask for a recall, the documentation required is like a small phone book! But when I rented a console and outboard to mix the Red Hot Chili Peppers' album [Stadium Arcanum], I just fell in love with the analogue equipment. And most of all, it's my 401(k), my retirement money! Seriously. That's how I convinced myself to buy all this gear. Once people find out I'm not very good and I have to stop working, I can immediately sell it and get all my money back. If you look at the racks, they contain very few new pieces of gear, not because I don't think the new stuff is any good — the Chandler stuff is amazing and JLM Audio makes some ridiculously good compressors — but because the old stuff won't go down in value. Also, a lot of the gear here comes from famous studios that have closed, like Sound City and Signet Sound.”