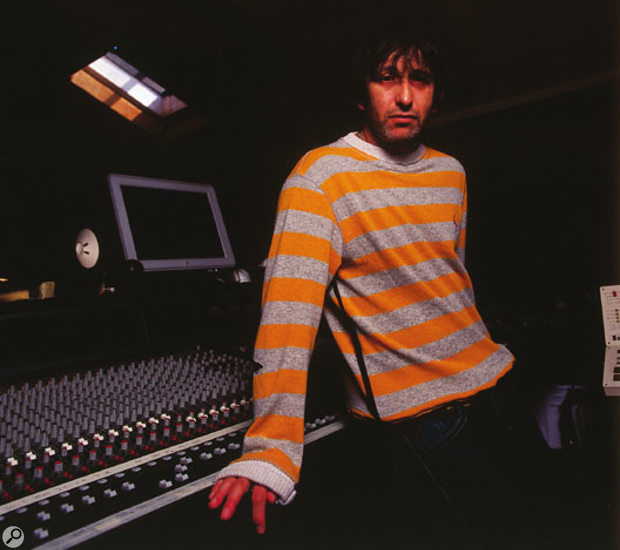

Since emerging from the Liverpool music scene at the turn of the '80s, Ian Broudie has juggled parallel careers as an artist and a producer. He has a new solo disc in the shops, and with albums by the Coral and the Zutons riding high in the charts, his production services are in greater demand than ever.

"There's very few producers who I have any respect for whatsoever," says Ian Broudie. In his view, studio recording and technology have reached a stage where the tail is wagging the dog. "You used to have a band who went into a studio and got a performance, and then you got all these things to try to make the performance easier — but it's almost gone full circle now, like those things have taken over. When you get a band, often the first thing people do is put it into Pro Tools, and it's almost like you're not giving the band a chance to not need that. If you're the producer, that makes your life much easier, because you can do the things that you do on any band. Therefore, the individuality of all those bands is just taken away a little bit, and you get this culture of things sounding like everything else, which is a lot of what goes on at the minute. That can be a good thing, depending on your aims, because then it gets played on the radio 'cause it sounds like all the other stuff on the radio and it fits in. But I think I've always wanted to do stuff that doesn't fit in."

An Eye-opening Experience

Over the last quarter of a century, Ian Broudie has managed to make an impressive career out of not fitting in. His first band, new wavers Big In Japan, never made it big outside Merseyside, but spawned an incredible array of successful ex-members, including Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Budgie of the Slits and Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bill Drummond of the KLF, and Teardrop Explodes' Dave Balfe, who would later found Food Records. Not to be outdone, Broudie made his mark producing artists such as Echo and the Bunnymen, the Primitives, the Fall, Sleeper and Alison Moyet, whilst his own Lightning Seeds project went on to even dizzier heights. He had a huge hit in 1989 with the single 'Pure' and follow-up album Cloudcuckooland, and four more successful albums followed before he retired the name after 1999's Tilt. Since then he's remained in demand as a producer, working with bands like the Coral and the Zutons, and he's also completed a solo album, Tales Told, the first to be released under his own name.

His introduction to the world of production happened almost by accident. "When I first went into a studio I was in Big In Japan, and down the road here there used to be a place called the Open Eye, where unemployed people could go and record, and they had two four-track TEACs and this weird little eight-channel desk, and I was the one who ended up working the tape machines and the desk. We started a record label called Zoo Records, and when we stopped, Dave and Bill said 'We don't want to be in groups any more, so can we have Zoo Records?' The rest of us went 'Yes,' so they said 'Great, we'd better do some records.' They went down the road 10 yards where Echo and the Bunnymen and Teardrop Explodes were, and said 'Do you want to do some records on our label?'"

Broudie was invited to oversee some Bunnymen sessions, an experience which gave him production credits on their first two albums and mixed feelings about the job itself. "I like producing things, but I don't like the thought of it being what I do all the time. There are great moments in it, but if it was something you did all the time, every day, I couldn't do that. I don't think I've got the attention span to work on things I don't like. I don't think I'm someone who covers all the bases. It'll be a disaster or it'll work out really well, and I'd rather it was like that. I've no desire to be able to work with everyone.

"I need to feel a certain way to work on something. I need to feel 'I wish I was in that band.' What I've always loved about certain groups, like the Bunnymen, was that they could play 'D' and 'G', and it sounded like the Bunnymen playing 'D' and 'G', it didn't sound like anyone else. It was just the chemistry between those people."

The control room at Elevator Studios is based around an Amek Mozart analogue desk.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

The control room at Elevator Studios is based around an Amek Mozart analogue desk.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

Telling Tales

Ian Broudie's new solo album Tales Told is the first he's produced under his own name, and is very different from the slick pop of the Lightning Seeds. Broudie's ear for a tune is as strong as ever, but he's abandoned drum machines and synths for a much more spare, acoustic sound. "I wrote 'Pure' in 1988 or something, and then the last time I recorded a Lightning Seeds track was 11 years afterwards, and I think sometimes you find yourself writing for something that's not who you are any more. I suppose it's like John Lennon singing 'She Loves You' — 10 years after that he's going 'Imagine all the people,' and it's a different fella. I probably wanted it to be very straightforward; quite stripped-down songs, with as little in between the song and the finished thing as possible, if that makes any sense.

"They're songs that are being performed, and I think it's fresh because it's the first time they ever are performed. They were all done pretty quickly. If people were around, then I'd say 'Play on it,' but 90 percent of it I played myself. There's bits of the Zutons, a couple of the Coral lads, someone from Ella Guru, the people who I knew from bands around Liverpool. On the four or five of them where there's other people as well as myself, there's very few overdubs — just the singing and the backing vocals. For a few of them I'd have an acoustic guitar and someone on drums. I'd teach them the song and I'd be playing it on acoustic and we'd go through it a few times and record the drums, and then I'd stick things over the top. There's a couple where there were more people around and we did it more or less live. We'd do bass, drums and a guitar and maybe something else. There wasn't any kind of a plan. I tend to not be very organised in a way, and I like that approach."

Catch 'Em Young

If Ian Broudie does have a specialism as a producer, it's working with young bands such as the Coral and the Zutons, who are often new to the recording studio. "I've always preferred to work with bands who are at the beginning of something. If you've got a great band and they're going to go in the studio and they haven't really done that much before, that's a real moment for me. It's a moment when they discover themselves, and you're creating a situation where their creativity can flourish. And they don't really know what they're like at that point — it's a voyage of discovery for everyone. And that shapes how they're going to sound for their whole career, that first album.

"I think it's really important for bands to find a way of being in a studio. They can be quite intimidating places sometimes, studios, and for young bands, they're not like the places they usually find themselves in, which is a rehearsal room or a gig that's got a certain vibe to it. I think a group is going to be better in a cool environment where they're not intimidated, where they can make a mess, they feel like they're somewhere where they can be at home very quickly, and creatively they're unrestrained. I think you'll make a better record in that situation than in a place where they don't feel like that but there's fantastic equipment.

"When you get a new band, I love the idea of not squashing them to fit the shape, but letting everything else fit them. I'd rather hear what they can do, than fit them into something. And that's a harder thing to do. Sometimes you might feel that you don't want a group to sound perfect. I've never really heard a band where, when they're playing through a song and then you put a click track on, the feel gets better. It's another situation where it's a means to an end. If you do it to a click track, it means you're going to be able to use your technology a lot better, or you can sequence things to it, so it opens up that world, but I've never known it be a better performance with a click track."

This large booth shares the top floor at Elevator Studios; there's a much larger, open-plan recording area downstairs.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

This large booth shares the top floor at Elevator Studios; there's a much larger, open-plan recording area downstairs.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

Elevated

Ian Broudie's fondness for stand-alone mic amps and different flavours of compression is well catered for at Elevator Studios: from top, API Lunchbox input channel, Neve compressor and EQ, Summit Audio and GML EQs, Audix EQ modules, Focusrite dual-channel compressor.Photo: Richard EcclestoneMost of Ian Broudie's recent projects, including his own album and those by the Coral and the Zutons, have been recorded at Liverpool's Elevator Studios. "I always used to work in my own places, out of not really liking many other places, but this has become home from home," explains Broudie. "It's a place that's just comfortable to be in. I always find, equipment-wise, you tend to bring the things you want to use with you, so the best thing for me in a studio is somewhere you want to be where you feel bands are going to be comfortable, and has speakers that sound something like they're going to sound when you go home. They're the two key things with me."

Ian Broudie's fondness for stand-alone mic amps and different flavours of compression is well catered for at Elevator Studios: from top, API Lunchbox input channel, Neve compressor and EQ, Summit Audio and GML EQs, Audix EQ modules, Focusrite dual-channel compressor.Photo: Richard EcclestoneMost of Ian Broudie's recent projects, including his own album and those by the Coral and the Zutons, have been recorded at Liverpool's Elevator Studios. "I always used to work in my own places, out of not really liking many other places, but this has become home from home," explains Broudie. "It's a place that's just comfortable to be in. I always find, equipment-wise, you tend to bring the things you want to use with you, so the best thing for me in a studio is somewhere you want to be where you feel bands are going to be comfortable, and has speakers that sound something like they're going to sound when you go home. They're the two key things with me."

With an open-plan control room on a separate floor from the main live area, Elevator Studios has been designed to fit into an existing warehouse space rather than built to order, and part of the reason Broudie likes it is that it's not a typical recording environment. "I love the fact that really you can't design studios, because there are too many variables. There's all these rules about the way you're supposed to build studios, but then you go in them and they never sound very good. All the ones they design seem to sound different, and they're always tweaking them and they're never quite happy with them. I always think you may as well start with a room, and if you're lucky, you might get one that sounds good. Most control rooms are dead and this is pretty live, with wood floors and brick walls. It's probably a bit of a fluke, but I always seem to know where I am in here. Partly, again, it's just being used to somewhere. A lot of the time, studios are dealing with people coming in who've never been there before, so you want somewhere where you can go from studio to studio and it be the same, but it never is. Everyone's got NS10s, but every set of NS10s sounds different depending on the shape of the desk that they're sitting on. Really, having the same set of speakers goes some way towards it, but there's so many variables that even in the same building, where they've got two rooms, usually there's one room that sounds very different to the other, and people like mixing in studio two but not in studio one."

Driving The Racing Car

Although Broudie had his own studios for many years, and has his share of engineering skill, he insists both that as a producer he doesn't want to be concerned with engineering decisions, and that gear choices are relatively unimportant. "I take all the technical stuff for granted. I'm like 'Yeah, you're going to put in a Teletronix, you're going to squash it down, you're going to get an EQ and you're going to use a different mic amp and you're going to put it through the desk and you might make it hit tape to get tape compression,' but that's not the important stuff. If Michael Schumacher gets into a racing car, he expects all that stuff to be going on — but then he has to drive it. It has to be done, and it's a very important part of the process, but it's not the bit that makes him world champion.

"At the end of the day, I don't really believe in equipment. There's treble and there's bass, there's compression and there's reverb, and that's it. No-one's invented anything else. At the moment there's a big propensity for using old equipment — most records are going through an enormous amount of old valve gear, and I don't think it has any relation to what you do. I think you can get anything out of anything. That stuff that the Beatles used to use, Freddie & The Dreamers used to use it as well. The difference is the Beatles, and the people who were working on those records and their vibe and ears and talent."

What does it mean to say that you can get anything out of anything? "Sometimes with guitar players when you're producing, a guitar player will have a certain sound, and you give them another guitar and another amp — and if you let them fiddle about they'll generally adjust it so it sounds like the guitar and amp that they started on, because that's the sound that they naturally like and the way that they play the guitar. In a way, it's like that when you EQ something. You tend to go for the sounds you like — whatever guitar and amp it is, you're going to get somewhere near the same thing." More of Elevator's processor armoury, including (from top) BSS four-channel DI, Valley People Kepex and Gain Brain dynamics units, Empirical Labs Distressor compressor, Drawmer DF320 noise filter, Ensoniq DP-Pro digital effects and two Gain Brain IIs. Photo: Richard Ecclestone

More of Elevator's processor armoury, including (from top) BSS four-channel DI, Valley People Kepex and Gain Brain dynamics units, Empirical Labs Distressor compressor, Drawmer DF320 noise filter, Ensoniq DP-Pro digital effects and two Gain Brain IIs. Photo: Richard Ecclestone

Nevertheless, Broudie does have some preferences when it comes to recording equipment. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given his emphasis on capturing the magic of a band performance, he prefers to record to analogue tape where possible: "The thing about digital recording is that every time something is invented, you get told that it's absolutely the same as tape and it's the bee's knees and it's perfect, and you're mad if you think it's any different. And then three years later they invent a better thing, and they say 'Yeah, what we did have wasn't so good, but now...' I don't believe anything except my ears. If it sounds OK, on an old Pro Tools or a new Pro Tools, I'm happy. And really, at the end of the day, tape is different. None of them are 'right', they've just all got a different character. You can do a good record on any of them, but certain things, like drums, I do prefer to put to tape. I like to hear the tape compression — but then I'm quite happy to transfer them over into Pro Tools to work on them after that.

"I don't record an awful lot through the mic amps on the desk, most of it gets recorded through other pathways. I really like having a lot of different types of compressors around, because I think every compressor is a bit different, and I'm quite up for different types of compression. We use the Universal Audio 6126 a lot, I like that, it's a quick and easy kind of thing. The Audix stuff I think is really good, and I really like the Summit EQs. I like the old Valley People Gain Brain 1s. The Distressor's really good when you absolutely need to hammer things, and I love the Crush setting on the Smart compressor. I like the APIs on the guitars and stuff, sometimes I'll use a Telefunken mic amp going into the APIs."

Shocking And Wrong

"Sometimes bringing a good guitar is going to be more use than bringing a good mic amp," says Ian Broudie.Photo: Richard EcclestoneOver the last few years, engineer Jon Gray has been pit mechanic to Broudie's Schumacher, freeing him from mundane technical matters to concentrate on the important things. Which are... what, exactly? "I think what people tend to do in the studio is to avoid making a decision by breaking things down into smaller decisions, but I think I prefer to make bigger decisions — and if it's wrong, it's wrong. Sometimes you've recorded a track and you just think 'This is the wrong tempo.' Those are the sorts of things that no-one ever says, in a funny way, but really it's an inescapable fact and you have to do it again. And then when you bite the bullet and do it again, sometimes changing the tempo can make a massive difference. It's an incredibly obvious thing, but sometimes everyone's concentrating on the little things.

"Sometimes bringing a good guitar is going to be more use than bringing a good mic amp," says Ian Broudie.Photo: Richard EcclestoneOver the last few years, engineer Jon Gray has been pit mechanic to Broudie's Schumacher, freeing him from mundane technical matters to concentrate on the important things. Which are... what, exactly? "I think what people tend to do in the studio is to avoid making a decision by breaking things down into smaller decisions, but I think I prefer to make bigger decisions — and if it's wrong, it's wrong. Sometimes you've recorded a track and you just think 'This is the wrong tempo.' Those are the sorts of things that no-one ever says, in a funny way, but really it's an inescapable fact and you have to do it again. And then when you bite the bullet and do it again, sometimes changing the tempo can make a massive difference. It's an incredibly obvious thing, but sometimes everyone's concentrating on the little things.

"I think a little bit of idiocy goes a long way in the studio, you know. Things that are unusual can sound shocking and wrong in the studio, but when you take them away, they sound fresh and exciting. When you're in the studio a lot of the time you can feel a pressure to go down a well-trodden road, and in the environment of a studio things often sound better like that, but when you take them away from the studio and listen in real life at home, things have a different cultural impact on you. You're going to perceive it in a different way in different situations, and sometimes you need to keep in mind how you will perceive it away from the studio."

Less Is More

Ian Broudie is being completely sincere when he says that to him, the best production is when it sounds like there's no production. "Sometimes as a producer, I feel that the best job you do is when you manage to do hardly anything. I think the best records sound like someone went in and it took them 10 minutes. I always think Dr. Dre records sound like that. It doesn't sound like they sat there for three days poring over it to make it a Blue Nile record. 'Be My Baby' is like that to me, and Pet Sounds, and all the records that I really, really like. They sound like they were done in a few moments of genius. I'm sure they weren't, but it's just a quality that they have, a directness. I think over the years it has been my obsession, not to make things sound like that, but to have those qualities — and I think those qualities are more in what you don't do than what you do. Like on my album and a lot of the stuff I do at the moment, there tends to be one reverb, maybe two, and I'll have it on a lot of the things. I don't really like it when they have lots of different reverbs. Another Broudie favourite is the Universal Audio 6176 tube preamp, here sitting above Tube-tech compressor and EQ and two Teletronix LA2A compressors. Photo: Richard Ecclestone

Another Broudie favourite is the Universal Audio 6176 tube preamp, here sitting above Tube-tech compressor and EQ and two Teletronix LA2A compressors. Photo: Richard Ecclestone

"The difference between a classic great record and a record that no-one ever plays is really small, which is why it's quite hard to do, and it's sometimes not what you'd expect that makes that difference. For me it's about capturing moments in time, and in a way with groups, I like the idea of just capturing a moment when that group is just firing on all cylinders in a natural way. And now technology allows us to take everyone's finest moments individually and put them in Pro Tools, but I still think that's a different thing to when you just get a magic moment that's just happened between everyone, rather than piecing everyone's magical moments together. When you get this thing that's just magic in a less thought-about way, and capture a certain feeling, a certain vibe, they're the moments that resonate.

"I've always thought the important things are tunes, vibe, and a sound that suits those tunes. When you go in to buy a stereo, the people who sell you stereos always have certain CDs that they play that make the stereos sound amazing — but they're very rarely records that you'd ever want to put on. And that's quite telling. I'd much rather make a record that people want to put on than one that shows off the stereo."