RME's Fireface 800 brings together all of the company's expertise in developing audio hardware for computers, mic preamps and converters into one highly desirable unit. But can you really fit so much functionality into one interface without cutting corners?

Over the last few years RME have established a reputation for high-end products in the desktop digital audio workstation market, with a range that encompasses audio interfaces for computers in the Hammerfall series, the ADI series of A-D and D-A converters, and the Quad Mic and Octa Mic microphone preamps. Given this fairly complementary product line-up, it was only a matter of time before RME combined elements of all of these in one product, and that's exactly what's happened with their latest offering, the Fireface 800.

As the name implies, the Fireface is a Firewire-based interface; and in addition to being RME's first stand-alone external Firewire device, it's also the first-ever Firewire 800 (IEEE 1394b) interface on the market. This doesn't mean, however, that you can't use the Fireface with a Firefire 400 (IEEE 1394a) interface: the Fireface is completely compatible with 1394a interfaces, and, in fact, the unit itself is supplied with a Firewire 400 cable. For this reason, since Firewire 800 is backwardly compatible with Firewire 400 anyway, you might be wondering why the Fireface being a 1394b-based interface is so significant. Well, in keeping with many of RME's other products, it's possible to connect multiple Firefaces to the same Firewire buss — up to three, in fact — but only Firewire 800 offers the necessary bandwidth to do this. So, in a nutshell, if you'll only ever want to use one Fireface, Firewire 400 is fine; if you want to use multiple Firefaces, you'll need to use Firewire 800.

Time For A Physical

The Fireface offers the same aesthetic styling as all current RME gear, with a clear, well laid-out front panel that is coloured a darker shade of blue than the rest of the unit. My only personal grievance with the look of RME gear at the moment is the ugly plastic faux rack handles added to the front panel, which I was delighted to find could be easily removed in just a minute with a screwdriver — all without voiding the warranty, I hope! Continuing on my mission to customise the look of the Fireface, I also removed the rack ears [as did our photographer — Ed], which makes the unit much neater to pop into my laptop bag for location work.

Getting back to the germane issue, the front panel features one unbalanced instrument input, four mic preamps with XLR connections (along with additional quarter-inch TRS line-input connections), and a series of indicator LEDs. These show the gain for the analogue inputs and outputs, the clocking of the digital ports, and various activity lights for MIDI and host connectivity. There's also a stereo headphone monitor quarter-inch TRS output, and, of course, the power switch.

The Fireface features four of RME's own mic preamps, and its A-D and D-A converters can operate at up to 192kHz. Photo: Mark Ewing

The Fireface features four of RME's own mic preamps, and its A-D and D-A converters can operate at up to 192kHz. Photo: Mark Ewing

Moving around the back, there's a single pair of MIDI In and Out ports, eight balanced line-level quarter-inch TRS analogue outputs, eight balanced line-level quarter-inch inputs, RCA connections for S/PDIF input and output (which are AES-EBU compatible), BNC connectors for word clock input and output, and two pairs of ADAT optical input and output ports. There's also a blank plate for the forthcoming Time Code Option (RME refer to this as the TCO), which will add video synchronisation abilities to the Fireface with the addition of BNC LTC input and output connectors, and a VITC input. Finally, the Fireface incorporates a built-in 100-240V power supply with an IEC connector also on the back panel, although this is fairly well isolated along one side of the unit. There's no fan, which means the Fireface itself is silent, but it can get a little warm when left on.

The Fireface features three Firewire ports (one Firewire 400 and two 800) with built-in hub functionality, meaning you can connect a Fireface to your computer and then daisy-chain other Firewire devices from the Fireface. As mentioned at the start of the article, it's possible to connect up to three Firefaces on the same Firewire buss, but you have to be using a Firewire 800 port in order to have enough bandwidth to make this possible. In fact, the increased bandwidth is the big advantage of using the Fireface in 800 mode, even if you aren't connecting multiple Firefaces. While the Firewire 800 port offers no improvements over the 400 port in terms of performance with just one Fireface connected, performance can suffer if you start daisy-chaining multiple Firewire devices, such as hard drives, with a Fireface on one 400 buss, whereas you won't run into these issues when using the Fireface on an 800 buss.

Firewire 800 Compatibility

Given that there are many different varieties of Firewire chip set on the market, it's important to check that you have a compatible Firewire interface before purchasing a Fireface, or, alternatively that you ensure you purchase a compatible Firewire interface before using the Fireface. To assist in this process, RME have published a useful Firewire compatibility guide on their web site (www.rme-audio.com/english/techinfo/fw800alert.htm), which is obviously of most interest to Windows users, since the Fireface is compatible with the Firewire chip sets used by Apple in Macintosh computers. For this review, I used a Lacie Firewire 800 PCMCIA card with my IBM Thinkpad, and can second RME's recommendation of Lacie Firewire interfaces for use with the Fireface.

There are also some compatibility issues to bear in mind with Windows XP Service Pack (SP) 2, which are also fully detailed on RME's web site (www.rme-audio.com/english/techinfo/fw800sp2.htm). Although Windows XP SP1 didn't support Firewire 800, according to RME the Fireface itself worked even though full 1394b performance wasn't achieved with every tested system. With SP2, Microsoft implemented support for Firewire 800 in accordance with the current Open Host Controller Interface (OHCI) specification, although, as RME's page goes on to explain, devices are switched to a transfer speed of S100 (100Mbits/s).

RME updated the firmware and driver for the Fireface to get around these problems with SP2, and if the driver detects SP2 is running on the host computer, the transfer speed is not switched to S100. Instead, one direction of data transfer is switched to S400, while the other direction stays at S800, so that the Fireface is fully functional, albeit without the full flexibility of true 1394b operation. I'm not sure how this would affect performance with multiple Fireface units on host computers with SP2, but if you're using this version of Windows and are interested in the Fireface, it's well worth checking with RME beforehand to make sure there are no surprises, despite the fact this problem has nothing to do with RME and has been affecting all manufacturers of Firewire 800 devices.

Analogue Inputs & Outputs

As you can probably tell from the line-up of inputs and outputs described above, to call the Fireface feature-rich is something of an understatement. The A-D and D-A converters are based on RME's stand-alone ADI series of A-D/D-A converters and offer support for sample rates up to 192kHz, at up to 24-bit resolution. There is a total of 10 analogue input channels, although the Fireface offers quite a bit of flexibility in how you actually use the 10 available inputs. As mentioned earlier, the back panel features eight balanced TRS inputs for the first eight channels, but there are also analogue-based inputs for channels one, seven and eight on the front panel. The gain on the inputs and outputs is selectable globally between three different levels, including +4dBu, -10dBV, and what RME describe as Lo Gain for inputs and Hi Gain for outputs, both equating to +19dBu at 0dBFS.

The channel one input on the front panel is an unbalanced TRS input with a gain control designed for a guitar or bass, and offers some interesting features for getting a better sound when DI'ing an instrument directly into a digital audio workstation. Firstly, there's a built-in soft-clipping function known as LIM that automatically limits any signals from -10dBFS, giving a soft distorted sound reminiscent of a tube-based overdrive if you completely overload the input, which is actually as great for Rhodes and Wurlitzer pianos as it is for guitarists.

When LIM is active, you'll see the red LIM LED light up on the front of the Fireface, and since there's no way to disable it, you'll need to make sure you keep the incoming signal below -10dBFS if you want a clean sound. While this might seem a little quirky, it actually helps to get a great dynamic sound from the instrument input, and you can always use the line-level input on the back of the Fireface instead if you're after a completely clean signal without the fear of soft clipping. It's also worth noting that even if you keep the input signal under -10dBFS for a clean result using the instrument input, you can still compensate for this to some extent by adding another 6dB of gain once the signal has been digitised by using Total Mix, which is described later in this review.

The Fireface serves as a Firewire hub, and up to three can be connected simultaneously to a Firewire 800 chain. Alternatively, various input and output streams can be disabled in order to conserve bandwidth on a Firewire 400 connection. Photo: Mark Ewing

The Fireface serves as a Firewire hub, and up to three can be connected simultaneously to a Firewire 800 chain. Alternatively, various input and output streams can be disabled in order to conserve bandwidth on a Firewire 400 connection. Photo: Mark Ewing

The instrument input also offers a dedicated drive function, which offers additional clipping and, as the manual points out "will blow you away" — with an extra 25dB of gain added to the signal, RME aren't kidding either. It's a good job you can enable and disable this feature manually! And if all of this wasn't enough, the instrument input also features a Speaker Emulation toggle to precondition DI'd signals to make them sound less dull and unmanageable once digitised by adding a little pre-clipping, removing low- and high-frequency noise and adding a small bass and presence boost.

Channels seven and eight, along with channels nine and 10, offer mic preamps taken from the RME Quad Mic and Octa Mic series, with easily accessible front-panel XLR mic inputs and additional balanced quarter-inch TRS line inputs, along with a gain control. Phantom power can be switched in for each of the four preamps independently.

Throughout the above descriptions, you'll have picked up on the fact that many of the channels feature multiple inputs, and it's actually possible for these inputs to be used simultaneously. This doesn't mean you get more than 10 analogue input channels for recording, though, it just means you get 17 analogue inputs that are submixed into 10 record channels — before the A-D conversion stage. You'll have to balance the levels yourself. For channels one, seven, and eight, however, you do have a little more control as you can set which inputs do get used in the Fireface Settings window, which we'll look at later. For channel one you can set either Line, Instrument or both, and for channels seven and eight you can specify either Mic, Line or both.

The analogue outputs are slightly more straightforward in that the first eight outputs go directly to the eight balanced TRS outputs on the back of the Fireface, with outputs nine and 10 reserved for a stereo quarter-inch TRS headphone output on the front of the unit. Having the headphone output is great, especially when you're using the Fireface in a mobile system, but a nice touch for those using the Fireface in a studio might have been to include a monitor output with a gain control for a set of speakers as well as headphones. While you can still hook up your monitor speakers to the Fireface, there's always something comforting about a hardware volume control over a software alternative, although RME's compromise by including a hardware-based monitoring system, which I'll describe later, does compensate for this to an extent.

The Digital Connection

As mentioned previously, the Fireface features two pairs of ADAT input and output ports, along with an RCA S/PDIF input and output, and as with other RME hardware, the second ADAT port can also be configured to be an optical S/PDIF output if required.

When working at 44.1 or 48 kHz, each ADAT port offers eight channels for a total of 16 channels of input and output. The Fireface also supports Double Speed mode (also known as Double Wire or S/MUX, for Sample Multiplexing) for 88.2 and 96 kHz operation, where the ADAT channels are combined to support the higher sampling rates, with the first ADAT ports offering channels one to four and the second ADAT ports giving channels five to eight. Although the ADAT ports could in theory be used for a Quad Speed mode (or Quad Wire), given that few other devices support this mode of operation, and since you'd only get two channels from each ADAT port, RME decided not to support this for the ADAT ports in the Fireface. Here you can see a Fireface-based Nuendo system being set to a 192kHz sampling rate in the Project Setup window.

Here you can see a Fireface-based Nuendo system being set to a 192kHz sampling rate in the Project Setup window.

The S/PDIF ports only support Single Wire, although they are still capable of handling sampling rates of upto 192kHz, assuming your other S/PDIF or AES-EBU devices support Single Wire 192kHz operation, of course. As on other RME devices, eight-channel interleaving is also available, so you can use the Fireface's S/PDIF output to connect with your home cinema setup for DVD playback. Very important, I'm sure you'll agree!

To summarise the inputs and outputs on the Fireface, at 44.1 or 48 kHz you get a maximum of 28 input channels (10 analogue plus 16 ADAT plus two S/PDIF) from a total of 35 inputs (eight back-panel analogue plus nine front-panel analogue plus 16 ADAT plus two S/PDIF), and 28 output channels (eight back-panel analogue plus stereo front-panel headphones plus 16 ADAT plus two S/PDIF). At higher sampling rates, the number of analogue inputs and outputs remains constant, along with the S/PDIF I/O, but the number of ADAT channels halves at 96kHz, and ADAT I/O becomes unavailable at 192kHz.

Fireface Settings

When it comes to actually using the Fireface, the centre of operations is the Fireface Settings window. If you've ever used an RME computer audio hardware device, this should look a little familiar, except for the fact it's an RME settings window on steroids! Rather than provide hardware controls for setting up the Fireface, with the exception of the gain controls on the instrument, mic and headphone channels, RME have arranged things such that all of the parameters are selected here. This includes input and output level gain, phantom power, and the Drive and Speaker Emulation options on the Instrument input, alongside the more conventional parameters for setting up RME audio interfaces, such as clocking, buffers, and digital I/O options.

I The Fireface Settings window offers a tremendous amount of flexibility, providing easy access to almost all of the unit's parameters in one place.n place of the usual selection of radio buttons for setting the buffer size used (and so the latency of the audio interface) in RME hardware is a pop-up menu to help save space. Unlike most of RME's PCI-based audio hardware, which offers a minimum buffer size of 64 samples (1ms latency at 44.1kHz), the Fireface offers values as low as 48 samples, alongside larger buffer sizes of 64, 128, 1024, 2048, 4096 and 8192 samples. However, there is a small caveat here because in order to ensure the reliable transmission of audio data over Firewire, the Fireface makes use of what RME term a 'Safety Buffer', which is a 64-sample buffer that's accumulated to the existing driver buffer on playback.

The Fireface Settings window offers a tremendous amount of flexibility, providing easy access to almost all of the unit's parameters in one place.n place of the usual selection of radio buttons for setting the buffer size used (and so the latency of the audio interface) in RME hardware is a pop-up menu to help save space. Unlike most of RME's PCI-based audio hardware, which offers a minimum buffer size of 64 samples (1ms latency at 44.1kHz), the Fireface offers values as low as 48 samples, alongside larger buffer sizes of 64, 128, 1024, 2048, 4096 and 8192 samples. However, there is a small caveat here because in order to ensure the reliable transmission of audio data over Firewire, the Fireface makes use of what RME term a 'Safety Buffer', which is a 64-sample buffer that's accumulated to the existing driver buffer on playback.

This means that the actual minimum playback latency is 48+64=112 samples, and the minimum theoretical software-based monitoring latency through an ASIO application such as Nuendo is 48+64+48=160 samples. As an example, with 48 samples set as the buffer size on the Fireface, Nuendo reported 1.134ms as the Input Latency and 2.585ms as the Output Latency with delay compensation enabled. And while the Safety Buffer might sound like a disadvantage, 112 samples is still acceptable, and it does ensure the Fireface works reliably, especially at higher sample rates such as 192kHz.

Staying with the subject of Firewire, another related setting in the Fireface Settings window is Limit Bandwidth, which, as you might expect, limits the bandwidth used by a given Fireface on the Firewire buss. This is achieved by restricting the number of channels used, and there are four settings available: All Channels, which basically gives you everything using the maximum amount of bandwidth, Analog 1-8, using only the first eight analogue inputs and outputs, Analog+SPDIF, which activates all 10 analogue inputs and outputs plus S/PDIF, and Analog+SPDIF+ADAT1, which disables only the second ADAT port. The Limit Bandwidth feature will be most useful for those using the Fireface with a Firewire 400 interface, as mentioned earlier, although the latter option to disable the second ADAT port is always worth making use of if you're not going to be using the second ADAT port so you don't waste bandwidth.

One particularly neat feature of the Fireface is that many of the settings configured in the Fireface Settings window are stored in the unit's internal flash memory, including the sample rate, clock mode, the setup of the channels and digital inputs and outputs, and the complete Total Mix configuration. This means that the Fireface returns to its previous state immediately after the unit is switched on, rather than waiting for the driver to initialise itself; it also means that, once set up for a given task, the unit can be used stand-alone without being connected to a computer. This feature really adds to the flexibility of the Fireface when you think about how many features the unit offers, and the manual suggests many stand-alone applications, such as A-D/D-A conversion, digital format conversion, monitor mixing, mic preamplification, and so on.

Driver Support

RME have always had possibly the best driver support of any range of audio cards I've ever come across, with regular updates and consistent reliability, and this extends to the Fireface. As it's a fairly new product, RME were continually posting new driver updates throughout the review period, including Mac OS X-compatible drivers towards the end. Occasionally, newer drivers will require you to flash the Fireface's firmware as RME add new functionality (such as Windows XP SP2 compatibility — see 'Firewire 800 Compatibility' box), although this takes just a few moments with the software updates downloadable from RME web site. Like the HDSP 9652, the Fireface features Secure BIOS technology, meaning that even if the firmware update fails, rebooting the Fireface will restore the old firmware so that you can continue to use the unit or try the updating procedure again.

The Fireface's drivers offer multi-client compatibility with ASIO 2.0, MME and GSIF 2.0 driver models for Windows 2000/XP users, and Core Audio and MIDI support for Mac OS X users running at least 10.3. GSIF 2.0 (GigaSampler Interface) is the latest driver model used by Gigastudio 3 (Gigastudio 2.5 used the GSIF 1.7 model), and, as with previous versions of GSIF, offers extremely low latency by operating at a kernel level. One of the new features of GSIF 2.0 is kernel-level MIDI support, so the Fireface's MIDI ports can now be addressed at a lower level by Gigastudio 3 for improved latency, and RME were actually the first developer to support GSIF 2.0, with suitable drivers having been publicly available even during the beta-testing stages of Gigastudio 3.

The multi-client nature of the drivers allow ASIO, MME and GSIF applications to be used simultaneously (it's even possible to run multiple ASIO applications at the same time) so long as each application runs at the same sample rate and doesn't share the same audio channels with another application. This latter limitation can be overcome by RME's included Total Mix system (described in the main text), which allows you to reroute or mix a playback channel to a different physical output.

Total Mix

I've mentioned Total Mix many times during this review, and while both Total Mix and RME's Digicheck analysis tool were discussed a year or so ago in the HDSP 9652 review, I'll recap briefly and point out the differences and improvements RME have made since the time of that review.

A year ago, the software to configure Total Mix was Windows-only, but the full Total Mix feature set, in terms of the software configuration, is now available to both Windows and Mac OS X users. However, Digicheck is still a Windows-only utility. Now at version 4.2, a new feature added to Digicheck since we last wrote about it is support for K-system metering, a new level-metering standard proposed by the well-known mastering engineer Bob Katz. You can learn more about this by visiting the relevant pages of Bob Katz's web site.

Total Mix presents the user with routing and volume controls for the audio inputs (before the audio reaches the host application), the playback channels (the audio output from the application), and the output channels (the audio output leaving the physical outputs on the card). This allows you to create monitor mixes without affecting how audio is recorded in your host application, by routing inputs directly to outputs, for example, or routing playback channels to multiple output channels. In the case of the Fireface, Total Mix is effectively a 1,568-channel mixer ((28 input channels plus 28 playback channels) x 28 output channels) operating with 42-bit precision.

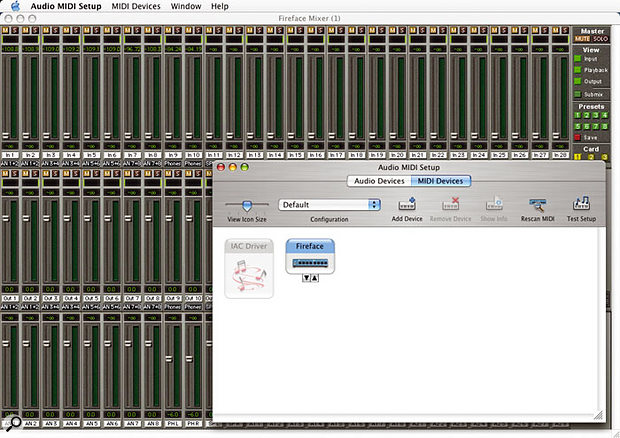

The Fireface is fully Mac OS X-compatible, and here you can see the Total Mix fader view in the background with OS X's Audio MIDI Setup utility showing the Fireface's MIDI ports in the foreground. Photo: Mark Ewing

The Fireface is fully Mac OS X-compatible, and here you can see the Total Mix fader view in the background with OS X's Audio MIDI Setup utility showing the Fireface's MIDI ports in the foreground. Photo: Mark Ewing

As you may remember from the 9652 review, rather than using an off-the-shelf DSP chip to power Total Mix and Digicheck, RME have implemented the DSP abilities of the HDSP family using an FPGA (Field Programmable Gate Array). These are chips where the actual logic and behaviour of the processor can be specifically programmed by the developer, allowing RME to provide the most efficient way of implementing the exact DSP functionality they need. The other benefit of an FPGA is that it allows RME to update the design of the chip at any time by providing the user with new firmware, making it possible to add new features or make any other adjustments.

The level meters in Total Mix offer a comparable level of accuracy to RME's Digicheck software, making them pretty valuable when you need to monitor the signals leaving the card. In use, being able to see the signal in the actual card is a great diagnostic facility, ensuring that audio is actually being output from the host application correctly. I've also been in situations where I've heard distortion even though the level meters in the host application looked fine; with further inspection in Total Mix, it became clear where the signals were peaking. You can also use the separate HDSP Meter Bridge application, which reads the hardware-based RMS and peak values for the given channels, for this purpose if you're looking for a less resource-intensive (but still accurate) metering solution.

When I last looked at Total Mix with the HDSP 9652 card, there was only the mixer-styled view for all operation, making it impossible to get an overview of the entire signal routing between all of the available channels. To overcome this, RME have since implemented the Matrix window, which is basically presents Total Mix to the user as a patchbay, with the input and playback channels listed vertically and the output channels listed horizontally. A connection can be made between any horizontal and vertical channel on the Matrix by simply clicking in the appropriate intersect slot, and you alter the level of the signal by Control-dragging with the mouse. The Matrix view is colour-coded so that 0dB connections are shown as green and connections greater or less than 0dB are black, while muted connections are orange. Unfortunately, though, there's no way to mute and unmute connections within the Matrix — this still needs to be done from the mixer view.

The only small criticism I have of Total Mix, which is actually quite understandable from a technical perspective, arises when you use multiple Firefaces in the same system. Although Total Mix provides a way of addressing the different interfaces, there's no way to bridge connections between multiple Firefaces, meaning that you can't route the first playback channel from the first Fireface to the first output channel on the second Fireface. Technically, the reason for this is that because Total Mix is a hardware-based feature, it has to work independently on each Fireface, and bussing the audio between Firefaces would make it impossible for Total Mix to achieve the near latency-free monitor mixing for which it was designed.

This handy block diagram, which is printed on the top surface of the Fireface, clearly illustrates the signal path of the unit and how the various elements interact with each other.

This handy block diagram, which is printed on the top surface of the Fireface, clearly illustrates the signal path of the unit and how the various elements interact with each other.

Relevant RME Reviews In SOS

Hammerfall DSP 9652

www.soundonsound.com/sos/jul03/articles/rmehammerfall.asp

Hammerfall DSP 9632

www.soundonsound.com/sos/nov03/articles/rmehdsp9632.htm

Quad Mic

www.soundonsound.com/sos/dec03/articles/rmequad.htm

ADI-8

Clocktastic

One of the reasons I really like RME hardware is that it tends to offer the most rock-solid clocking of any device in its price range, and the company always seem to be actively developing new digital audio clocking technologies to further improve this functionality.

RME's Sync Check is of course implemented in the Fireface, providing status information on the incoming clock signals from the possible external sources. When Autosync mode is active (as opposed to the specified Master mode) in the Settings window, the unit will if possible automatically slave itself to your preferred, selected source, or the most stable clock input from either ADAT, S/PDIF, word clock or its own internal clock (if no external source is detected). One important note is that if multiple Firefaces are connected in the same system, each must be clocked individually so that additional Firefaces are slaved to one master Fireface, or all Firefaces are clocked to whatever your master studio clock signal might be. The DDS page in the Fireface Settings window allows you to recalibrate the sample rate clock, effectively tuning your digital audio workstation up or down. This is most useful for those who need to work with pull-up or pull-down frame rates in video.

The DDS page in the Fireface Settings window allows you to recalibrate the sample rate clock, effectively tuning your digital audio workstation up or down. This is most useful for those who need to work with pull-up or pull-down frame rates in video.

A newer clocking technology that has found itself into recent RME products, such as the HDSP MADI and ADI 648 (of which SOS reviews will be forthcoming very soon), along with the HDSP 9632, is Steady Clock, which, simply put, provides a method of cleaning up a clock signal. Steady Clock was originally developed to overcome the reasonably high levels of jitter inherent in a clock signal distributed over MADI, although it also has great application in cleaning up clock signals generally, whether they're from an ADAT source, word clock, and so on. The bottom line here is that using Steady Clock should dramatically improve the stability of your clocking with efficient jitter suppression, especially when using the inherent clock signal in digital audio transmission formats, which means you'll get the highest possible quality achievable from the A-D/D-A converters. Another added bonus is that if you're clocking any devices from the Fireface using word clock, any word clock input to the Fireface is automatically cleaned up by Steady Clock, giving you a much cleaner clock signal on the word clock output.

The most intriguing clock-related feature that RME are debuting in the Fireface (and which is soon to be featured in other products such as the HDSP MADI) stems from the fact that RME use a Direct Digital Synthesizer (DDS) for the internal clock rather than a quartz crystal. This means that it's possible for the internal clock of the Fireface to operate at practically any required frequency, as opposed to only 44.1 or 48 kHz, for example, which is particularly useful when working with video.

If you work in post-production, or any area of music where film is involved, you'll probably have come across the terms pull-up and pull-down, which, simply put, mean that the sample rate is deliberately changed in order to slow down or speed up audio to compensate for a change in the speed (or frame rate) of film. This is usually necessary when transferring between different frame rates, such as when picture is converted between PAL and NTSC or film and video. The most common factors used for pull-ups and pull-downs are changes of ±0.1 percent or ±4 percent, and these are provided as preset options in the new DDS page in the Fireface Settings window, along with Coarse and Fine sliders for even more accurate sample-rate recalibrations. As an example, 0.1 percent pull-ups and pull-downs are used for transferring audio between 30 and 29.97 fps (frames per second), or 24 and 23.976 fps, while you'd use 4 percent pull-ups and pull-downs for going between 25 and 24 fps.

For those working with video, the DDS features of the Fireface would really enhance any computer system used for post-production, especially since these features aren't readily available in applications like Nuendo.

Conclusion

The Fireface 800 was first announced at the Winter NAMM show in January 2004, and there has certainly been a great deal of anticipation surrounding its release, especially with all the promised functionality and Firewire 800 support. Once again, RME have lived up to expectations and the Fireface offers an incredible amount of functionality and flexibility, implementing everything the company does so well in one small, 1U box.

RME say that they took the Hammerfall DSP Multiface as the starting point for the Fireface, and certainly the Fireface takes everything that was great about the Multiface and adds everything that was lacking, creating one unit that provides Swiss-army-knife audio functionality for anyone on the road with a laptop, or in the studio requiring a Firewire audio interface that 'has it all'. The fact the Fireface has a stand-alone mode that enables you to use it for a variety of other applications only enhances its usefulness. At the end of the day, all I can say is that the only thing I sent back to RME after I'd finished reviewing the Fireface was my credit card number!

Alternatives?

While the Fireface is without competition if you're looking for a Firewire 800-compatible audio device, there are, of course, many alternatives if you're looking at Firewire 400 devices, most notably from MOTU and Metric Halo. MOTU's 1U 828 MkII offers similar functionality for those on a smaller budget, with 10 channels of analogue I/O at up to 96kHz, one pair of ADAT I/O, S/PDIF I/O, two mic/instrument inputs, a Cuemix monitoring facility, plus SMPTE synchronisation and ADAT 9-pin Sync. The company's 2U 896HD offers 192kHz support across eight channels, each with a preamp, plus S/PDIF I/O and one pair of ADAT I/O ports.

For Mac OS users who have a slightly larger budget, Metric Halo offer the 1U Mobile I/O range, which includes the 2882 with eight channels of 96kHz conversion and preamps, S/PDIF I/O and the ability to draw power from the Firewire buss, or the ULN2, a two-channel version of the 2882. Metric Halo also offer versions of these interfaces with onboard DSP that provides a routing window and onboard effects such as dynamics and EQ.

Pros

- The first Firewire 800 audio interface makes daisy-chaining multiple Firewire devices, including multiple Firefaces, on the same buss possible without performance issues.

- One Fireface can be used on a Firewire 400 buss without limiting functionality.

- Brings together RME's technologies, including Total Mix and the new DDS video-related features, in one great box that is portable enough to take on the road.

- Up to 192kHz sample rates can be used on the analogue inputs and outputs.

Cons

- I can't think of a reason for not buying a Fireface if I was looking for a serious Firewire-based audio interface.

Summary

The Fireface is an amazing unit that brings together RME's strengths in audio interfacing, converters and preamps into one neat Firewire-based package.

information

£999 including VAT.

Synthax Audio UK +44 (0)1664 410600.