In the second part of our masterclass on the production of modern metal music, we explain what makes a great metal mix.

The way music is balanced, equalised, processed and effected has an overwhelming impact on the way it is perceived. In extreme metal, a good mix is usually characterised by hyper‑realism of performance and tightness of production, with a particular emphasis on low‑end definition, overall clarity and intelligibility. Despite the fact that each mix will present its own specific challenges, this article aims to explain basic techniques that are common practice within the genre. With time and experience, these will serve as a starting point for developing your own personal mixing style.

Mixing is a creative process, and it's important that you aren't continually distracted by technical issues. So it's a good idea to carry out all the technical preparation on your files before getting stuck in. Start by getting rid of any unwanted audio from your project: for unwanted sections where toms are not being used, as well as incidental bass and guitar string and amp noise, waveform edits with appropriate fades are a lot more accurate than trying to get manual gates to operate correctly. If you're going to be using samples to replace or reinforce your drum tracks, now is the time to add them (see 'Drum Samples In Metal Mixing' box).

Time Alignment & Phase

Paying attention to phase issues can often make the difference between a clear, well‑defined mix that has a heavy yet tight low end, and one that is thin, with poor intelligibility. Start by ensuring that your various kick‑drum sources (multiple mics and samples) are phase‑coherent, by fading each source in with one of the kick mics, and comparing this without, and then with, the phase inverted. Usually, one of these settings will provide a much thicker, fuller low end, and clearly this indicates phase summation.

After doing the same with your individual snare tracks, I can recommend that you spend time experimenting with time‑aligning your overheads to your snare spot mics. It is amazing how much difference bringing the overheads just two or three milliseconds earlier in the digital domain will make to the overall body and tone of the snare when these sources are combined, due to improved phase coherence. Simply line up a significant transient on your overheads to the same transient on your snare top channel by zooming right in to the waveform display as far as possible, then physically shift the overhead audio files earlier so that this transient is starting at exactly the same point. Room mics can likewise be time‑aligned to your snare spot mics.

As phase cancellation is a very common problem with a multi‑miked kit, all other spot mics should now be checked against the overheads for phase, and polarities reversed if appropriate.

Like sample reinforcement, re‑amping the bass guitar is common place in metal mixing. However, a common mistake is the failure to realign the re‑amped track to the DI, to take into account the delay introduced by this signal path. Even a couple of milliseconds is enough to introduce comb filtering, which will thin out the bass sound when the re‑amped cab is combined with the DI. You can make this realigning task a lot easier by flying in a signal with a sharp transient attack (such as a cowbell) before the start of the DI track before you re‑amp. Afterwards, simply zoom into the cowbell's waveform on the re-amped track, and time‑align this to exactly the same point on the DI track.

Even if re‑amping has not been used, it's usual to record at least one DI and one amped bass track, so there is still the possibility that time‑alignment/phase issues will need addressing. Use the DI signal as the central reference. Once all the individual bass channels are time‑aligned and reinforcing each other, make sure that the collective bass sound is phase‑coherent with the kick drum; failure to get this right will result in a vastly weakened low end.

If you have double‑miked your guitar cabs for each take, and the diaphragms were placed as close as possible to each other, there shouldn't be any phase issues here; and as any re‑amped guitar tracks will not be combined with the DI source, it is not so vital that these are time‑aligned.

Although checking all these phase issues may seem rather time‑intensive, it's invariably time well spent.

Grouping The Groups

At this point, your session should be edited, time‑aligned and fully phase‑summated, with the snare, kick, toms, bass and guitar gated or edited and the samples lined up. You can now set up any mix groups you want to use. Remember that using equalisation and compression on individual channels can give very different results from using the same processes on groups: for example, applying EQ to four rhythm guitars separately will provide a profoundly different tone from applying a single EQ across the whole rhythm guitar group.

All producers will have their preferred approach, so instead of stating my own preferences, I would rather emphasise the importance of experimenting with the various options, by exporting relevant sections and A/B'ing the results. However, I definitely would not recommend processing your kick drum and bass guitar on the same group, as I have heard suggested by some people. Boosting or attenuating the two instruments at the same frequency will increase the likelihood of an unnatural accumulation, or gaps, in the frequency spectrum.

Finely Balanced

As ever, the most important element of mixing is balancing the relative levels of all the instruments and, if necessary, using automation to control them. It is very hard to generalise about balance levels, because, obviously, every mix is different, but we can give a few guidelines that usually apply to extreme metal mixes.

First, contrary to popular belief, red lights from level peaking are not a sign of virility when mixing loud, powerful music! As a general rule I recommend keeping at least 6dB of headroom right across the board on individual channels, groups, effects auxiliaries and the master bus.

To achieve the required tightness of sound, the drum sound will usually be dominated by the spot mics, so be careful not to overplay the level of your overheads and any room mics. Overdoing the overheads will very quickly lead to an abrasive mix that will soon tire the ears of the listener. It is usually appropriate to make the kick drum(s) slightly higher in volume than the rest of the kit: not only is the weight and presence of the kick essential in providing a strong foundation to the mix, but the kick tends to get pushed down when overall mastering compression is applied — as, to a lesser extent, does the snare.

Bass guitar often tends to get overshadowed by the drums and rhythm guitars, and again, master compression can exaggerate this, so bear in mind the likely effect of any mix processing when you're setting bass levels.

Vocal levels need to be determined by the style and type of performance. Some bands I've mixed have actually requested that the vocals be given less prominence, to divert attention more towards the grooves, guitar riffs and general power of the instruments. In this situation, try overdriving the vocals using a plug‑in such as Digidesign's Lo‑Fi.

The best extreme metal mix engineers in the business have developed an uncompromising dedication to detail, and as you get more experienced and proficient at mixing, so will you. Examples of paying attention to detail might include riding up the overheads to provide additional energy during choruses, automating big reverbs on key snare or floor-tom hits, riding certain bass notes or phrases, and emphasising pinched‑harmonic guitar squeals and vocal segments with long, panning delays.

Panning & Stereo Width

Good stereo width, which will provide a big soundscape, is essential. However, you need to be very careful that this is not to the detriment of the centre of the mix: when instruments are panned inappropriately wide, the centre can sound unfocused and slightly detached, with an apparent hole in the middle.

First of all, think about how wide your overheads should be panned to provide as realistic a perspective as possible, avoiding excessive movement across the stereo field.. From here, ideally, the panning of the tom mics should mirror their perceived positions in the overhead mics. In many instances, a more natural focus will be provided by bringing the pan position of the overheads inwards slightly, which has the added bonus of leaving the extremities of the stereo field free for the rhythm guitars.

Equalisation

Before getting into detailed discussion about equalisation, I firstly want to present two errors that many novices to the metal genre, make with their EQ decisions. One is the tendency to focus on only boosting rather than attenuating frequencies. This will, of course, increase the overall level of the audio, which can mislead us into thinking that it sounds better when it doesn't. Boosting has its place, but it's important to remember the value of corrective attenuation. For example, cutting with a tight (higher) 'Q' setting can remove, or significantly reduce, resonant or undesired frequencies. It might not be as 'ear‑grabbing' as a big boost but it may be more effective.

Another novice error is to spend too much time manipulating and fine‑tuning EQ choices while assessing the individual instruments or audio tracks in isolation. This can be useful, particularly when finding unwanted resonant frequencies, but audio always needs to be judged in context, and this is never more so than when dealing with the heavy, dense tonalities of extreme metal. Therefore, the impact of your EQ decisions as they sound within the mix should always take priority.

Filter Away

One of the biggest challenges in modern metal production is getting the low end of the mix right. In striving for a 'heavy' production, many mixers will excessively amplify the wrong low‑end frequencies, resulting in an uncontrolled, boomy and flabby mix. Alternatively, a production with a deficiency in the right bass frequencies will lack impact and sound thin.

One of the keys to getting this aspect of the mix right is to create a very specific space for each instrument to sit and breathe. This will partly be achieved by avoiding masking: the tendency of one sound or instrument to obscure, or inhibit another in the same frequency region. This is particularly important in the low end, where getting the bass right is not so much a case of boosting low frequencies as of removing inessential energy in this region, so that instruments that need to sit here have space to 'breathe' in.

To achieve all of the above, I can't stress enough the importance of integrating high‑pass filters (HPFs) into your equalisation decisions. When these are used correctly, the treated instruments will be perceived as being louder and more defined, and there will be more clarity in the overall mix. I will often use HPFs on every single instrument, and the busier the mix, the higher the corner frequency that will be selected for each filter. Particularly for a dense, Dimmu Borgir‑style production with fast double kicks, blast beats, string sections and keyboards, extensive and aggressive use of HPFs is necessary to help retain intelligibility for all these instruments.

As a general rule for mixing extreme modern metal, I would use an HPF to remove anything below 60Hz right across the mix, and would avoid boosting anything in the 20‑60Hz sub‑bass range, which invariably will wreck a mix for this genre. Obviously, every instrument in every project will have vastly differing frequency content, and although you can't use a formula when applying high‑pass filters, I will present the following as a general guide.

For kick and snare, an HPF will be used to remove everything below the lowest desirable frequency. With the kick, this can be anywhere between 60 and 80Hz, depending on the style and speed of kick pattern (low frequencies on kick drums have a tendency to 'build-up' with quick kick drum work), while on the snare it would typically be between 110 and 170Hz. A large floor tom would be treated in a similar manner to the kick, with the cutoff frequency higher on smaller toms. I frequently have the HPF on the overheads and hats as high as 550Hz, but lower, around 400Hz, for the ride. Tonal control over each separate element of the drums is essential for gaining the punch and clarity required. The overhead mics are thus not used so much to provide an overall 'picture' of the kit, but more as spot mics for the cymbals. With this in mind, the HPF on the overheads and hats can be set as high as 550Hz. Getting this right can easily be done by concentrating the ear on the high‑frequency content while slowly moving the HPF up until it starts thinning out the cymbals or hats, then moving the setting back slightly. A slight boost in the 10‑12kHz region has been applied in this screen shot to add some definition and brightness. Room/ambient mics can have an HPF set anywhere between 80 and 250Hz, dependent on what you want them to bring to the mix.

Tonal control over each separate element of the drums is essential for gaining the punch and clarity required. The overhead mics are thus not used so much to provide an overall 'picture' of the kit, but more as spot mics for the cymbals. With this in mind, the HPF on the overheads and hats can be set as high as 550Hz. Getting this right can easily be done by concentrating the ear on the high‑frequency content while slowly moving the HPF up until it starts thinning out the cymbals or hats, then moving the setting back slightly. A slight boost in the 10‑12kHz region has been applied in this screen shot to add some definition and brightness. Room/ambient mics can have an HPF set anywhere between 80 and 250Hz, dependent on what you want them to bring to the mix.

The bass guitar HPF I will usually leave at 60Hz, dependent on how busy the bass performance, kick drums and mix in general is. It is essential to remove the cabinet thump and resonant low‑end rumble from rhythm guitar tones, and depending on what key the guitars are down‑tuned to, this will involve an HPF set anywhere between 65 and 105Hz. Vocals very rarely have any content below 85Hz, and the HPF can usually be set a lot higher, perhaps around 160Hz, depending on the tone and style of the vocalist.

Although they are used nowhere near as frequently as HPFs, low‑pass filters can also be implemented to remove high‑end noise or hiss, and can also be used to mark the highest usable frequency. For example, rolling the bass off above 7/8kHz can help minimise masking and therefore increase separation.

Intelligent EQ

Having removed unwanted frequencies, you can now use additional EQ and balancing to pick out the tones that really matter. However, before discussing some frequency guidelines for specific instruments, I first want to mention three general principles that can be highly effective.

- To gain a louder, tighter and more powerful mix, avoid simultaneously amplifying or attenuating the same frequency on too many different instruments. Boosts at the same frequency on multiple instruments have the tendency to accumulate, and sound unnatural and unpleasant, with an unpredictable overall mix level due to the resulting 'loud' region created in the frequency spectrum. Likewise, making the same frequency cuts on multiple instruments can result in an artificial‑sounding 'gap' in the production's frequency range, making the mix unstable on different systems. So, for instance, you would usually avoid amplifying or attenuating both your kick drum and bass groups at the same frequency, and avoid boosting or attenuating the same frequency across all the different kick and bass tracks. By varying the frequencies being amplified and attenuated, you will achieve a more balanced tonal distribution and a louder, heavier mix as a result.

- Think about attenuating instruments that are masking, rather than boosting the one that is being masked. For instance, a snare may lack impact because it is being masked by other instruments around the 200Hz region where, generally speaking, the body and weight of a snare is. Rather than simply amplifying the snare at 200Hz to fight the other instruments for this range, and in the process cause an unnatural accumulation of frequencies here, you should experiment with attenuating the 200Hz region on the instrumentation that is masking the snare.

- On the same principle, it is worth experimenting with 'mirroring' your EQ choices, whereby the amplification of a certain frequency on one instrument is paired by the attenuation of the same frequency on another relevant instrument. By doing so, less gain can be used whilst achieving the same impact of a much greater boost, and generally speaking, the audio will sound less processed and much more natural as a result. To use an example, whether you are dealing with the growls of a death‑metal vocalist or a performance featuring high‑pitched screams, the vocals are predominantly going to be in the mid‑range. In the battle to achieve as big a guitar tone as possible, you may have problems in gaining proper vocal clarity and intelligibility if there is not enough room in the mid‑range for the vocals to sit. Find a frequency range in the vocal sound which contains pleasing tonal characteristics, and combine EQ boosts to accentuate this with attenuation of the same range on the rhythm guitar group.

Where The Meat Is

As already stated, every instrument in every project will have vastly differing frequency content. Therefore, although the following can be used as a rough guideline, your decisions should clearly be informed, above all, by the frequency content of your source material.

- Kick Drums

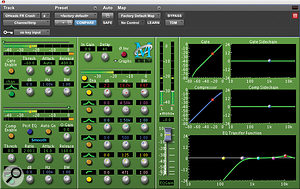

This screen shows typical metal kick‑drum EQ and compression settings, with gating taken care of via a side‑chain. Similar EQ settings could be applied to a kick sample prepared from the same kit. A high‑pass filter at 65Hz minimises inessential low‑end energy, while a parametric boost at 82Hz, with a medium 'Q' setting, emphasises the 'right' band of low frequencies. The third band is extensively attenuating unwanted frequencies around 341Hz, providing more definition and clarity and freeing up space for the bass guitar to 'breathe'. Finally, a fairly gentle boost at 3.62kHz and a larger one at 7.22kHz emphasise the attack. When an even more cutting impact is required, the boost at 7.22kHz could be replaced with one at an even higher range, around 9‑10kHz. The compressor's attack setting is allowing the initial transients of the kick drum through untouched before clamping down on the body with a relatively high ratio — again, helping to emphasise attack.

This screen shows typical metal kick‑drum EQ and compression settings, with gating taken care of via a side‑chain. Similar EQ settings could be applied to a kick sample prepared from the same kit. A high‑pass filter at 65Hz minimises inessential low‑end energy, while a parametric boost at 82Hz, with a medium 'Q' setting, emphasises the 'right' band of low frequencies. The third band is extensively attenuating unwanted frequencies around 341Hz, providing more definition and clarity and freeing up space for the bass guitar to 'breathe'. Finally, a fairly gentle boost at 3.62kHz and a larger one at 7.22kHz emphasise the attack. When an even more cutting impact is required, the boost at 7.22kHz could be replaced with one at an even higher range, around 9‑10kHz. The compressor's attack setting is allowing the initial transients of the kick drum through untouched before clamping down on the body with a relatively high ratio — again, helping to emphasise attack.

The fundamental low‑end weight of a kick drum will usually be around 60‑110Hz. However, avoid amplifying any frequencies lower than 75Hz, as this will usually result in a mix‑wrecking accumulation of boomy frequencies, particularly on sections with fast double‑kick patterns. To provide more clarity and definition to your kick, whilst additionally freeing up a space and a place for the bass to breathe in, there is usually some unwanted energy in the 250 to 450 Hz frequency range that can be aggressively attenuated. The all‑important click of the kick drum is usually found either at around 4kHz or an octave higher at around 8kHz; the latter, in particular, often needs to be dialled in to provide maximum clarity for fast double‑kick performances.

- Snare Drums

Although there is little that is specific to extreme metal when it comes to EQ'ing snare drums, it is worth mentioning that, generally speaking, the weight and body of a snare is centred around 200Hz‑450Hz. Amplifying parts of this range will thicken up the snare tone, and cutting will produce a brighter snare with more of a 'crack'. There are often also some 'boxy' frequencies between 175 and 500Hz, which should be located by sweeping around in the normal way and then attenuated. To further increase a snare's attack, boost around 4‑8kHz or accentuate the rattle of the snare wires around 10‑12kHz.

- Hats, Toms, Ride & Overheads

Other than making sure that your toms have the requisite weight and attack, there is little here that is specific to the genre. Any necessary brightening up to provide definition for the kit's 'metalwork' can be added using a broad, gentle boost around 10‑12kHz. Any harshness in the overheads is usually located in the 3‑6kHz region.

- Bass

As discussed in last month's article, recording a channel of bass amp simulation is an excellent way of getting an alternative tone and coverage of frequencies to strengthen the DI and mic combination. Additionally, a channel of distortion will provide separate control over the driven element of the bass sound: experiment with removing the abrasive high end and muddy lows this distortion can produce by using high and low‑pass filters at around 250‑400Hz and 2‑5kH respectively. Band‑limiting the bass distortion channel can remove the muddy lows and abrasive highs that may be created by bass distortion. The solid bottom end will be provided by the other bass sources.

Band‑limiting the bass distortion channel can remove the muddy lows and abrasive highs that may be created by bass distortion. The solid bottom end will be provided by the other bass sources.

Lack of bass guitar in the mix seems to be the hallmark of most amateur metal productions. The distorted element helps to get more volume from the bass without it sounding inappropriately loud, as it gels better with the guitar tones. The attack, note definition and presence of a bass guitar can often be emphasised by boosting around 2‑3.5kHz. A clearer, less woofy bass tone with accentuated lows and highs can be achieved by using corrective EQ on the bass group in the low mid‑range around 200–450Hz where the guitars may be fighting for space. Experiment with widening the 'Q', but avoid heavily attenuating the same frequency ranges on bass and kick drum.

- Guitars

Avoid the tendency to immediately try to dial in a lot of low frequencies for the rhythm guitar tracks, as this is one of the surest ways of ending up with a muddy, flabby low end to a mix. After setting the HPF as appropriate, it is generally inadvisable to focus on amplifying the 65‑80Hz range; after all, the guitar is not a bass instrument, however much it is tuned down! A tighter tone with stronger note definition can usually be achieved by boosting slightly higher, at around 85‑120Hz. In this example, I have used eight bands of EQ for rhythm guitar. The all‑important HPF has been set to 85Hz — very close to the low‑frequency area being boosted, which is 89Hz. Three dips are applied to control unwanted resonant frequencies at 123 and 186Hz, both with an extremely tight 'Q' curve, and 2.39kHz, with a wider 'Q'. High‑end brightness is added at 6.86kHz, and on the second screenshot, a slight high‑mid boost with a wider 'Q' has been applied at 1.82kHz to compensate for the attenuation at 2.39kHz. Finally, an LPF has been used to mark the highest usable frequency and to help minimise masking; in this instance, it was set to 12.4kHz.

In this example, I have used eight bands of EQ for rhythm guitar. The all‑important HPF has been set to 85Hz — very close to the low‑frequency area being boosted, which is 89Hz. Three dips are applied to control unwanted resonant frequencies at 123 and 186Hz, both with an extremely tight 'Q' curve, and 2.39kHz, with a wider 'Q'. High‑end brightness is added at 6.86kHz, and on the second screenshot, a slight high‑mid boost with a wider 'Q' has been applied at 1.82kHz to compensate for the attenuation at 2.39kHz. Finally, an LPF has been used to mark the highest usable frequency and to help minimise masking; in this instance, it was set to 12.4kHz.

The mid‑range of guitar tones, where most of the character and personality is found, is too often overlooked. Heavily mid‑scooped guitar tones will often result in a thin‑sounding production, but there are often unwanted, resonant, boomy low‑mid frequencies around 250Hz as well as 'pillowy' frequencies at around 1.5‑2.5kHz, which may need attenuating to keep them under control. If appropriate, a slight boost with a wide 'Q' can then be applied at around 1‑2.5kHz to compensate for the upper mid‑range cut, helping to provide a thicker tone when required. The essential high‑end brightness for rhythm guitars will usually be found between 5kHz and 8kHz.

Having tried many of the hardware and software amp/cab simulators on the market, I still feel that these cannot compare with the more organic and natural sound of the real thing. If you have used a simulator for your rhythm guitar tone, beware of an abrasive high end that can sometimes interfere with the clarity of the cymbals. You can use a low‑pass filter to correct this.

- Vocals

Heavy attenuation of unwanted resonant vocal frequencies is common to most genres. However, in this instance, mirrored EQ has been used to gain the necessary vocal clarity against huge, down‑tuned rhythm guitar tones: the pleasing vocal characteristics around 3.79kHz have been boosted, while the same region has been cut on the rhythm guitar group.

Heavy attenuation of unwanted resonant vocal frequencies is common to most genres. However, in this instance, mirrored EQ has been used to gain the necessary vocal clarity against huge, down‑tuned rhythm guitar tones: the pleasing vocal characteristics around 3.79kHz have been boosted, while the same region has been cut on the rhythm guitar group.

Even if the lyrical content of the band you are mixing is indecipherable, ensuring that the energy and emotion of the vocal performance is translated with clarity and intelligibility is still essential. With this in mind, to make sure that the vocals cut through the aggressive high end of the guitars, you will often need to dial in a lot of high‑end brightness around 4.5kHz, and possibly some 'air' at 10‑12kHz. However, amplifying this frequency range can often lead to problems with sibilance on vocal tracks, so a de‑esser should be inserted over each and every vocal channel before they get EQ'ed. Experimenting with a small amount of overdrive can help the vocal sit better in the context of the mix, by providing a warmer, slightly more aggressive tonal character. A small level of overdrive (in this instance provided by Digidesign's Lo‑Fi plug‑in) applied to the vocal can provide a warmer tonal character.

A small level of overdrive (in this instance provided by Digidesign's Lo‑Fi plug‑in) applied to the vocal can provide a warmer tonal character.

Compression

The basic principles of compression have been covered in depth in SOS recently, so in this article I'll stick to specific applications for metal mixing. Generally speaking, the faster and more intense the performances involved, the more heavy‑handed you will have to be with your compression settings. In some instances, for example when going from blast beats to a half‑time section, automation will still be required. If you are uncertain about exactly what effect your compression is having on the audio, I can highly recommend exporting the compressed file and examining the waveform. This is great for visualising exactly what the compression is doing, particularly to the source's attack. Similarly, be aware of the impact compression is having on frequency content: badly compressed audio will quickly lead to a muddy mix.

To use a compressor to emphasise a kick drum's attack, set the compressor's attack relatively slow (above 20 milliseconds) so that the initial transients are retained but the body is compressed. Use a fast to medium release and set the threshold fairly low. Conversely, if you want to add more body to, for example, your snare, set both attack and release times really fast (within a few milliseconds), with the threshold set so that it is compressing the snare's attack, but not its body. Although overheads can sound more aggressive with compression applied to them, I personally prefer the pin‑point accuracy of uncompressed overheads. However, ambient room mics will usually benefit from very heavy‑handed compression.

In instances where particularly aggressive levels of compression are required, for example with bass, two separate compressors in series can be a lot more effective at providing a constant perceived level than a single compressor. Different parameter settings should be used on each compressor: for example, the compression on the channel could be set to clamp down on just the peaks of a bass signal by having a high threshold with a fast attack, while a group compressor to which the bass is routed could be set with a lower threshold and slow attack, so that it is compressing the body of the bass sound. Either way, higher ratio levels that are more associated with limiting (8:1/10:1) can often still be required. Achieving a constant vocal level will often require a similar approach, but opt for a very fast attack and medium release.

I rarely compress rhythm guitars, as by their nature, overdriven guitars are already very compressed. If you do feel you need to compress them, opt for a low ratio and slow attack, to retain note definition.

Effects

My initial advice on the subject of reverb would be to keep it simple, and send many different instruments to just two, or maybe even one, reverb. Using a lot of different reverb treatments will, in effect, put different parts of the mix into many separate spaces, which will probably sound ineffective and inappropriate.

As a general guide for the snare and (to a lesser extent) toms, I would use a short plate reverb with a decay of between 500 and 800 milliseconds and a pre‑delay (to set the reverb away from the initial transient attack) of between around seven and 11 milliseconds. Experiment with the send levels between your snare top, bottom and samples: sending more of the latter can help to provide a really effective stability to the overall snare reverb. Leave the rest of your kit dry, as well as your bass and rhythm guitars.

A drum‑production trick well worth experimenting with, when appropriate, is brightening up your reverb return. Try removing the low‑frequency content of the reverb return below 200Hz, boosting its presence at around 3‑4kHz and possibly adding 'air' at around 10‑12kHz.

When mixing a track that features intense performances and dense tonality, I will often opt to keep the vocal track in the same acoustic space as the drums, by bussing them to the same short plate reverb. When there is space to do so, it can be appropriate to use a longer reverb on the vocal, but be very careful with the level applied, as too much can quickly result in a lack of definition. I will therefore apply more delay than reverb to the lead vocal, usually opting for a simple eighth‑note repeat. The same vocal reverb and delay will be used for any guitar solos, and I will often have an additional really long delay set up as a special effect for vocals or guitars.

Conclusion

Of all musical genres, metal is the very last that is acceptable when delivered with poor production. A quick search of MySpace will reveal that there are some absolutely superb musicians and bands out there, with great songs, whose talent, unfortunately, is utterly lost in the appalling production and mixes of their demos. In my opinion, metal is the most glorious music in the world after classical music. Hopefully the techniques, procedures and approaches covered in these articles will enable the quality of your productions to measure up to the music!

Drum Samples In Metal Mixing

Due to the consistent dynamics, power and attack required, one of the distinctive aspects of extreme metal production is the widespread use of drum samples. Usually, this will just be for the kick and snare, but occasionally for the toms, when required. There is always a balancing act: samples should contribute to the right drum sound, but without the performance sounding as though it has been programmed. Provided the live drums have been properly recorded, most producers will prefer the more natural‑sounding approach of using samples to reinforce or augment the live tracks, rather than replacing them altogether.

Although I sometimes combine them with other pre‑prepared samples, I will predominantly use drum samples taken from the kit used for recording, as these will interact with the spot and overhead mics in a much more natural way. In last month's article I recommended spending time preparing different combinations of the spot, overhead and room mics when bouncing down to create these samples. It is at this stage that you should take time to experiment with how these different samples work within the context of the relevant spot mics and the overheads. The tempos, style and speed of the drum performance will also have a large bearing on sample selection: for example, it would be inappropriate to use a really ambient snare sample for a thrash‑style track, or where blast beats are used.

We saw last month that it is worth recording the output of drum triggers if you can. These are very useful for implementing samples, or opening gates via side‑chains, as they will have less bleed‑over than conventional mics. If you are forced to use the close‑miked kick and snare tracks as sources, it's worth taking some time to ensure that hit points aren't being missed, and checking that samples have not been added where they shouldn't be.

There are several ways of implementing drum samples. Some producers prefer to use the Tab to Transient feature in Pro Tools to paste each sample in manually, while others use software packages such as Sound Replacer, TL Drum Rehab and Drumagog. Whichever method you use, it is absolutely essential that the samples are perfectly lined up and in phase with the live drum hits. Outside of quiet sections, use minimal or no sample dynamics whatsoever on the kick, and if your drummer used two separate kick drums rather than a double‑kick pedal, tune one of your samples slightly differently, to provide an element of differentiation between the two.

One of the main indicators of poor sample use is lack of dynamics on snare rolls, so this is an area where time will need to be spent either on getting the dynamics to track those of the performance, or using volume automation to introduce variation.

Drum Samples & Side‑Chain Gating

In this screen shot, the top (brown) channel is the un‑gated snare top mic. The centre (blue) channel is the same signal, but with inaccurate auto‑gating applied. The bottom (green) track shows the same section, but with side‑chain gating applied. As we can see, the auto‑gating has affected the crucial transient attack of the first snare hit, and severely truncated the buzz‑roll occurring after the second hit.

In this screen shot, the top (brown) channel is the un‑gated snare top mic. The centre (blue) channel is the same signal, but with inaccurate auto‑gating applied. The bottom (green) track shows the same section, but with side‑chain gating applied. As we can see, the auto‑gating has affected the crucial transient attack of the first snare hit, and severely truncated the buzz‑roll occurring after the second hit. Highly accurate gating, without the risk of truncating the all‑important transient attack, can be achieved by copying the already implemented drum samples to a new track, moving these 10 milliseconds earlier, and then feeding them to the side‑chain of the relevant spot‑mic gate.

Highly accurate gating, without the risk of truncating the all‑important transient attack, can be achieved by copying the already implemented drum samples to a new track, moving these 10 milliseconds earlier, and then feeding them to the side‑chain of the relevant spot‑mic gate. I've found that there are limitations to the effectiveness of automatic noise gates within various music production platforms. They can be inaccurate and unpredictable when it comes to opening fast enough to allow the wanted audio through. Some gates have a 'look‑ahead' function, in a bid to combat this issue, but often with mixed results. These shortcomings mean that, as you will see from the screenshot on the left, the transient attack of a drum hit can get slightly truncated. The first few milliseconds of a drum hit are absolutely essential to its attack and definition, and any 'softening' of a drum's attack is obviously unacceptable in an extreme metal production.

The good news is that once you have lined up your kick and snare samples, these can provide a reliable source to feed the side‑chain input of your kick and snare mic gates. Simply copy all of your kick or snare samples to a new track and collectively move them 10 milliseconds earlier to provide the gate with just enough time to accurately open and allow through the all‑important transient attack. You don't want to hear this duplicate sample track, but it should be routed to the side‑chain input of the relevant gate.

Set the gate quite tight, with the range at maximum, so that nothing is heard when it's closed. Heavy gating facilitates absolute tonal control over each separate element of the drums, which will be essential to gaining the punch and clarity that is required.

One last point on side‑chain gating: now that your kick and snare side‑chain gate sources are in place, these can be used to experiment with side‑chain gating room mics you have recorded, to allow just the kick or snare ambience through. This can provide a different impact from using room mics in a standard way, helping add weight, punch and size to kick and snare spot mics.

Listening Levels & Environment

Given the power and volume levels that are associated with metal, it is tempting to predominantly mix at a loud level. However, the best way to assess the instrumental and frequency balance of a mix is actually to not only listen at different levels, but also on many different systems (including car stereos and headphones), in different environments, and even in different listening positions within these rooms.

Master Bus Processing

To ensure that no nasty surprises leap out at the mastering stage, try inserting a compressor or a mastering‑style plug‑in over your stereo output bus in the latter stages of mixing, but removing this prior to exporting your final mix. This will give you a general idea of what balance and frequency impact mastering compression is going to have. Keep the ratio fairly low (no more than 2:1) with a fairly high threshold, providing no more than 3 or 4 dB of gain reduction.

Listen For Yourself!

All the screenshots for this article were taken from my mixes for modern metal acts For Untold Reasons (left: www.myspace.com/foruntoldreasons) and Godsized (www.myspace.com/godsized). Audio examples demonstrating these settings and the techniques discussed in this article can be found on line at /sos/dec09/articles/metalaudio.htm.