From elaborate band arrangements to their pioneering collaborations with Giorgio Moroder, Sparks' music has always been innovative and instantly identifiable.

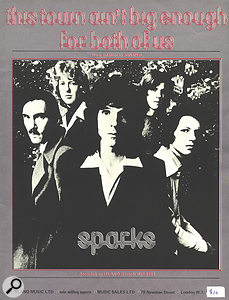

In a career lasting 45 years, Californian brothers Ron and Russell Mael, trading together as Sparks, have carved out a reputation as musical pioneers, and have been name-checked by such diverse figures as Kurt Cobain, Paul McCartney, Morrissey and the members of Abba. From their early days in Los Angeles, where they recorded two albums as Halfnelson, through their big hits of the 1970s — the propulsive glam rock of 'This Town Ain't Big Enough For Both Of Us', the dancefloor pulse of 'The Number One Song In Heaven' — and onto their homespun electronic albums from the 1990s onwards, the Maels have remained eclectic musicians with a certain skewed pop Ron (left) and Russell Mael of Sparks today. nous.

Ron (left) and Russell Mael of Sparks today. nous.

The brothers have kept pace with technological change, from fiddling with reel-to-reels in their '60s student days, through constructing huge productions with the likes of Muff Winwood, Tony Visconti and Giorgio Moroder, to employing their own digital studio in singer Russell Mael's living room. Whatever the approach to recording, however, they have never sounded anything other than recognisably Sparks, as evidenced by their latest release, the 81-track retrospective box set New Music For Amnesiacs, The Ultimate Collection.

"There isn't a hard dividing line between the technology and what you are as a band,” argues Ron Mael, the duo's keyboard player and chief songwriter. "We've always been aware of that, and that's why we've always tried to put ourselves in situations with different producers or different instruments or different kind of concepts. We realise that all those things are what enable us to get to where we wanna be as musicians. It isn't like a classical pianist showing up at a concert, and there's a beautifully tuned Steinway and that's all he needs. We realise that there has to be a lot of choices that you can make.”

Sparks have been around to witness and enjoy both the huge recording budgets of the past and the carefree, pressure-less advantages of working with digital audio workstations today. "We've really been lucky, because things have come along as far as technology goes at just the right times for us,” says Ron. "When the whole record company backing of recording was kind of dissipating, then the ability to record without having to go into an expensive studio came along. We're not tech-geeks in one sense, but in the other sense, we really know how to use things to get what we want. I think we always have, even from the very beginning.”

Backwards Is Better

As devout Anglophiles, in thrall to the British beat boom sounds of the 1960s, Ron and Russell Mael first started making music while students at UCLA in the latter half of that decade, with their friend and first guitarist Earle Mankey, who had built a very basic recording studio at his home.

"At that time,” remembers Russell, "it was just really primitive, the recording technology and the process that we had. Earle had a tiny apartment and a couple of reel-to-reel tape recorders and so we could just record things. But it was pretty forward-thinking, even at that early stage. All of us were really eager to be doing things that made use of the studio as opposed to being a live band where you wanted to just Sparks in London, November 1972 (from left): Ron Mael, Jim Mankey, Harley Feinstein, Russell Mael, Earle Mankey. recreate a good performance of the band playing altogether. We would use these two tiny seven-and-a-half-inch-per-second machines, bouncing things from one machine over to the other. Obviously you'd lose fidelity all the time, but you'd also gain some kind of quality to the recording by building up all the hiss on the tape.”

Sparks in London, November 1972 (from left): Ron Mael, Jim Mankey, Harley Feinstein, Russell Mael, Earle Mankey. recreate a good performance of the band playing altogether. We would use these two tiny seven-and-a-half-inch-per-second machines, bouncing things from one machine over to the other. Obviously you'd lose fidelity all the time, but you'd also gain some kind of quality to the recording by building up all the hiss on the tape.”

"We didn't have a piano,” Ron recalls, "so we'd go into the piano rehearsal halls at UCLA. The three of us would take the tape recorder down and do backwards piano recordings while people were kind of wondering what we were up to. Everybody was really traditional as far as piano went, and we kind of liked it sounding backwards more than forwards.”

At the time, Ron had two keyboards: a cheap organ bought from US department store Sears, and a Wurlitzer electric piano. "The electric piano was really beautiful and the sound was amazing,” he says, "but the keys would break every five minutes.”

The demos that the trio, now named Halfnelson, recorded together came to the attention of artist and producer Todd Rundgren, who oversaw the making of their eponymous debut album in 1971. "It was intimidating for us just to be in a studio,” Ron says. "But he was really incredibly open to what we were doing, and I think we really felt like kindred spirits, even though some of his own music was kinda maybe more soul-based. But he was an Anglophile just the way we were Anglophiles. It all went incredibly well with him personally and musically.”

"To his credit,” Russell adds, "he didn't wanna change what we were doing, he just wanted the fidelity to be a little better. So we were going into an expensive recording studio with Todd, but still banging on cardboard boxes and all. He could see that the recording process was kind of a part of what we were. It wasn't that we needed to be changed into a traditional band. The way we were recording was a fair part of what we were and what made us interesting as a band to him.”

'Wonder Girl', the band's first single and the opening track on New Music For Amnesiacs, spotlights their unorthodox pop approach. "Todd really wanted to preserve the quality of the demo,” says Russell. "It's not like a live band sound at all. The guitar parts are really deliberate. The recording has a real character to it.”

The band with film director and kindred spirit Jacques Tati.

The band with film director and kindred spirit Jacques Tati.

"The keyboard on that was the Wurlitzer,” says Ron.

"It was always difficult for me to figure out how a keyboard really worked with a band. So in that particular song, it was kind of a two-note riff.”

Atlantic Crossing

One key fan of the Halfnelson album (re-released as Sparks in 1972) and its 1973 successor, A Woofer In Tweeter's Clothing, was Muff Winwood, Island Records' A&R man and in-house producer. He signed the band and arranged for them to relocate to the UK, where they began to flourish, recording their landmark Kimono My House album at Basing St Studios (now SARM West) in Notting Hill, London, and the Who's Ramport Studios in Battersea over the winter of 1973/74. "It was at the time there was all the power crisis going on in England,” Russell says, "so we had to work around the schedule of when there'd be electricity in the studio. I remember we were always half on standby waiting to hear, 'Well, you can go in tomorrow, but you have to start at six o'clock 'cause that's when there'll be power in the Battersea region.' It was bizarre, especially for us being from LA... just kind of disorientating.”

The record showcased Sparks' passion for experimental, rock-heavy pop, but as Ron says, to their ears, the band didn't sound unusual at all. "We kinda had delusions that we were somehow another version of the Who, really. We obviously wanted to do stuff that interested us, and we also thought to not have interesting lyrics is just a waste of time. But we never thought of ourselves as particularly experimental in what we were trying to do. We thought we were just a band.”

Nearly 40 years on, breakthrough hit 'This Town Ain't Big Enough For Both Of Us' remains a dazzling production, with its stabbing piano riff, pummelling beat, octave-leaping vocal and gunshot sound effects. "With the gunshot in 'This Town',” says Ron, "we were trying to decide whether that was incredibly cheesy or something that was all right. So we went back and forth all the time on that. Then it sounds like we used any kind of gunshot, but we went through a whole BBC library and found the perfect gunshot for that song. In the end, it was used tastefully, so it didn't become kind of a novelty song.”

of a novelty song.”

In a change from their early albums, Sparks were keen to capture the sound of a live band on Kimono My House, before adding its characterful keyboard and vocal overdubs. "That's really it,” says Ron. "All of the tracks were played live with the band and then we'd record extra guitars and maybe an organ or a Mellotron or whatever else was needed. And obviously extra vocals were added. But Muff was a really big believer in a band feel.”

"The other thing that really was a part of the sound at that time was Ron's synthesizer,” adds Russell. "He was using an RMI, but it sounded too basic, it didn't have a lot of character on its own, so he used an Echoplex tape delay unit with it.”

"It was the first time I was really aware that technology can give some kind of mystery to the sound,” Ron says. "There was a kind of haunting quality to the RMI with the Echoplex. Real tape delay gave it a little of a wobbly feel. That sound, these days, you can approximate it, but to get that thing, you need the old gear. I'm not a big collector of vintage gear, but I kept that Echoplex, 'cause it's just such a beautiful machine.”

From A Spark To A Flame

Moving on to its follow-up, Propaganda, released a mere six months later in November 1974, Sparks began to expand their sonic palette. The opening title track, for instance, featured a massed chorus of stacked Russell Maels, in a sound and technique later appropriated by one-time Sparks support act Queen. "We hadn't noticed,” jokes Ron.

"Just stacking vocals up like that,” says Russell, "even if you have no echoes and no reverbs or anything, it's gonna give it a quality, just 'cause of the tone of the singing and then the choice of the parts that you sing. And then just the amount of times you stacked them up. It wasn't such an issue what types of effects were put on that, because I think the effect of just doing that is strong and then you add reverbs, big or small or whatever, to give it a certain extra character.”

One track that employed reverb to full effect was Propaganda's orchestrated, almost Phil Spector-ish ballad 'Never Turn Your Back On Mother Earth', replete with harpsichord and Mellotron parts, which became Sparks' third hit in late 1974. "It was one of the few ballads we'd ever recorded,” says Ron, "so we wanted to try to make it sound really impressive. I guess that use of a lot of reverb was a way to make it so that it wasn't just a singer-songwriter kind of thing and it had the power of an aggressive song.”

Indiscreet in 1975 marked a change of producer from Muff Winwood to Tony Visconti, whose work with Marc Bolan and David Bowie the Maels much admired. Visconti helped fashion the sound of the brilliantly bonkers hit 'Get In The Swing', with its tempo shifts and strident marching-band figures.

"Tony has this amazing sensibility of what pop music should be,” says Russell, "and he's also an accomplished musician, so he can draw from sources that aren't pop sources for any kind of ideas that you might have. With 'Get In The Swing', we had thought that it could use this sort of marching-band sound, and with our five-piece group we obviously didn't have the means or know-how to achieve that. But if you mention a marching band to Tony, then he is able to score that to sound really authentic and then to incorporate that into the track.”

Subsequent '70s albums brought diminishing commercial returns, however, and Sparks began to tire

of a rock-based sound. "We just thought we'd taken it as far as we could,” Ron explains. "I mean, obviously in a few years we would return to that. We didn't want to abandon a band, but we wanted to just go broader in what we were doing. From our standpoint, we're always anxious to mutate in some kind of way.”

Love Is In The Air

Becoming increasingly fascinated by the developments in synthesizers and sequencers, particularly the groundbreaking sound of Donna Summer's 1977 hit 'I Feel Love', in 1978 the Maels travelled to Munich to work with its Italian-born electronic producer Giorgio Moroder at his Musicland Studios. The result was the album No.1 In Heaven, released in 1979, which saw Sparks change their sound entirely, to great commercial effect, with the trancey 'The Number One Song In Heaven' and the punchy, hypnotic 'Beat The Clock' both becoming hits in the UK.

"The idea had enticed us,” says Russell, "and we were curious to know how using that sort of electronic background would work with Ron's songwriting and my singing. But the idea was to use it in a non-club sort of way, which had been the connotation of Giorgio Moroder's productions up to that time. We still saw what we were doing as being a band, but just using a different musical backdrop. Giorgio was really up for that challenge, as well, because he had never worked with a band before and he thought that that could maybe open him up to other ways of working.

"When that album was first heard, some people were taken aback, 'cause we were considered a rock band up 'til then. It was a really bold and provocative album to do at that time. We were pleasantly surprised that it had as much commercial success, for something that initially was kind of controversial. Then obviously with time, the whole history of that album has been rewritten where it is now seen as a Bible for that whole genre of music.”

Working with Moroder's modular Moog synths was, the Maels remember, something of a challenge. "So much trial and error, and so many options,” Russell says. "It was like the old telephone operator thing where you're patching two phone calls together. You were patching sounds together. But the whole idea of sequencers, back then it was kind of primitive in that everything was divided into 16th notes. By pulling one plug out of one of those 16 slots, it left a hole, and that's what gave you the stutter on that particular beat.”

Initially, the drum track was provided by a Moog-simulated kick, before drummer Keith Forsey came in to add a live beat. "Keith would just spend 16 minutes hitting a kick drum to a click and then add fills after that,” Russell explains. "I think that's also what gave that album less of a robotic feel. It had some bit of humanity to all the electronics because all the drumming was live.”

"The downside,” Ron adds, "was that just because of the nature of the technology, we were never able to do that album live until the mid-'90s, because there was no way to bring a synthesizer the size of a building with you onto the stage.”

Following No. 1 In Heaven, and the less successful Moroder-produced follow-up Terminal Jive in 1980, Sparks returned to their rock sound. The 1980s were something of a wilderness period for Sparks, however, with a run of albums that struggled commercially as they unsuccessfully attempted to divert into film-making.

Sparks are enthusiastic adherents of home recording. Their current setup is located in singer Russell Mael's house and is based around MOTU's Digital Performer DAW.

Sparks are enthusiastic adherents of home recording. Their current setup is located in singer Russell Mael's house and is based around MOTU's Digital Performer DAW.

Back Home

It wasn't until 1994, when they formed their own Lil' Beethoven Records and released the home-recorded Gratuitous Sax & Senseless Violins that Sparks enjoyed something of a resurgence in popularity. The album was rooted once again in electronics, with the breakout hit 'When Do I Get To Sing My Way?' echoing their Moroder records. Both of the Maels say that being able to program their music in their own studio freed up their creative process.

"That album was made in my living room,” says Russell. "People are shocked to know that. You couldn't have imagined doing, like, the No.1 In Heaven album at home, but now there were means to do it. With Gratuitous Sax we had computers, but we did a couple of albums before that where we used a Roland hardware sequencer. Even with ADATs and flying vocals around, you needed a maths degree to be able to figure out how to copy one part to another section of a song. Looking back it was a nightmare, but the job got done in the end, even if the task was a lot harder to do technically.”

When computer-based recording became a reality, the Maels started using MOTU's Digital Performer, and have stuck with it ever since. "It was the first software we ever used,” says Russell, "even before there was digital audio, and it was just a MIDI sequencer. We still use it, because in the end all of them do basically the same thing, and everyone ends up stealing the better elements from the other digital audio workstations. It's always hilarious to us when someone says, 'So you guys use Pro Tools?' And you go, 'Well, no.' Then it's almost like, 'Oh you don't? Oh gosh, how sad.' But you tend to stick with what you're comfortable with and what you first learn.”

With what they cheekily called their "career-defining opus”, 2002's Lil' Beethoven, Sparks used programming to move into a more classical sound, centred around orchestral patches from their Yamaha S80. "It had some sort of arpeggiator,” says Ron, "and the thinking behind that album was we wondered if there was a way to have an aggressive kind of sound that wasn't using guitars. We weren't out to make some sort of pseudo-classical album at all. We had written a lot of songs previous to that that were gonna be our next album, and we kind of felt that maybe we were just going through the motions and that we really had to rethink things. So we went at that album from the start without any songs. We usually go into our studio with songs, at least in some kind of way, but this time we went in just using the instruments and saw what we could come up with. I mean, I know that's the way a lot of people work anyway. But to us, that was new. We were able to then work backwards and figure out vocals that would go with different things.”

and figure out vocals that would go with different things.”

Hand To Mouth

Sparks' most recent project is a live album, Two Hands One Mouth, focusing on their stripped-back touring production of the same name, which involved the Maels appearing on stage with just one Motif XF8 keyboard — the back panel of which bears the word 'Ronald' spelled out in the distinctive Roland font — set on a simple piano patch.

"We have a lot of sound libraries,” says Ron, "and we were thinking of bringing a computer and having that on the side of the keyboard just to have more variety of sounds. But we didn't want to have any kind of appearance of it not being completely live. It's a frightening experience for us, because we've always either toured with the safety of a band or computers. But with this there's nothing to fall back on, and if your mind starts drifting at all

during the set, you're screwed. It gives us a certain mental concentration in our old age.”

The brothers compiled the record from 15 recordings of shows in Europe. Live albums are very rarely entirely live, however. Were there any sneaky little tweaks involved? "No, we stayed away from sneaky little tweaks,” Russell laughs.

"We were lucky enough to have so many choices,” Ron points out. "We went for the quantity recording approach in order to make it tweak-free.”

Four-and-a-half decades into their career, Sparks show no signs of slowing down. Their long-held filmic ambitions are soon to be realised with a feature-length version of their 2009 album, The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman, a concept album that imagined the Swedish movie director visiting Hollywood in the 1950s.

Similarly, they are now working on a new album with a narrative theme, though Russell Mael is tight-lipped about the exact details. "We're well into the project, though some of the elements of the narrative are changing,” he says. "But it'll be a compelling story.”

Much, of course, like the story of Sparks themselves.

What's A Good Mic For Mael Vocals?

Perhaps surprisingly, given his distinctive vocal style, Russell Mael claims to have no preference when it comes to choosing microphones. "All that stuff, it doesn't seem important,” he says. "For me, it's just about the material and the performance and doing it in a certain way. Tony Visconti told us that people will ask him, 'How do I get that Marc Bolan guitar sound?' And he says, 'Be Marc Bolan and you'll get that sound. That was how he played guitar and that was the sound that came out of his amplifier.' So it's the same sort of thing with me in a way with vocals, it's just the sound that comes out. With a hundred different microphones, it's gonna sound very close to what it sounds like with any of the other hundred microphones. Obviously there's subtleties and purists might say, 'Well, you need this mic or this mic.' But to us, that's less important. The really important thing to us is just capturing the performance.”