The Leonards: Patrick Leonard (left) and Leonard Cohen at work in the latter’s house.

The Leonards: Patrick Leonard (left) and Leonard Cohen at work in the latter’s house.

In search of reality, Leonard Cohen convinced his producer Patrick Leonard to abandon his hang-ups about using sampled instruments.

“I’m slowing down the tune, I’ve never liked it fast / You want to get there soon, I want to get there last,” croons Leonard Cohen on ‘Slow’, the funny and catchy opening track of his latest album, Popular Problems. It’s ironic, in this context, that the Canadian chose Patrick Leonard as his main collaborator, which resulted in songs coming together, according to Cohen in a recent interview, at “shockingly alarming speed”. Patrick Leonard co-wrote seven of the album’s songs with Cohen, and produced all nine. ‘Slow’ was written and recorded at his log cabin home studio in the mountains north of Los Angeles.

“‘Slow’ was the first song we wrote together for this album. Leonard sent me the lyric via email, and I printed it out, sat down at the piano, and took half an hour to write the song — noting the music on the lyrics sheet — and then to record a demo in Logic. I sent the demo to him via email, and he immediately wrote back, saying ‘Great!’ And it was done. Next song. That’s how it went.

“The demo had my guide vocal, a kick drum, a bass, organ and Fender Rhodes, and it occurred to me to also add sampled horns. Later on I went to Leonard’s place to record his vocals, we added female background vocals at my place, and finally we mixed the song, and that was it.”

“The demo had my guide vocal, a kick drum, a bass, organ and Fender Rhodes, and it occurred to me to also add sampled horns. Later on I went to Leonard’s place to record his vocals, we added female background vocals at my place, and finally we mixed the song, and that was it.”

Inside The Obvious

Despite its swift gestation, ‘Slow’ is an extraordinary piece of work, with a powerful atmosphere and the kind of effortless and graceful melody that one imagines Leonard uncovered rather than wrote. “With [Cohen’s previous album] Old Ideas,” says Patrick Leonard, “I was still trying to get to know Leonard and to inject my own perspective on things. With this new project the nature of our relationship was a little different, and I felt freer to do what I felt worked best, and to just do what I love. In working with Leonard, it was very demanding to come up with things that were simple and yet intelligent. It was hard to maintain a stringent and strict set of rules, and my main rule was that I could not do anything that would make the music more important than the lyrics. It was pretty difficult to make music that matters, and yet does not draw attention to itself, that is utilitarian, yet also is meaningful and purposeful. There were just a few places on the album where I did things you wouldn’t expect, where there were those weird twists that I tend to look for, because they make me happy. During my career I have tended to look for those unexpected things, instead of going for, say, the obvious chord. But lately and particularly in working with Leonard, I have more often gone for the obvious, which means that you need to look inside of the obvious to find meaning and authenticity.

“There was no technical sophistication in the way this was done. None. Zero. With Old Ideas I worked mostly at Leonard’s studio, which is upstairs in a guest house on his property. I wrote most of the material for the new album at my place, where I have all my keyboards, some nice preamps, like Neve 1073s and 1076s and APIs, some vintage outboard like an LA2A, Urei 1176s, Pultecs and so on, and Logic and Pro Tools HD systems. The studio is in my living room, and acoustically treated with [ASC] Tube Trap wall units. I also have a big garage that is soundproofed and has tie-lines and is where I record drums. At Leonard’s place I used my Neumann U47, a Vintech Audio preamp, which is a Neve 1073 clone, an Apogee Duet, a Mac with Logic 9, a set of AKG headphones, Genelec speakers, a Nord Stage and an 88-key Akai controller. The latter plays terribly, but it forced me to play in a way that worked for the album. Leonard also has this Technics keyboard, and we set up like anybody would in a garage.

Much of the music on Popular Problems was composed by Patrick Leonard using a Mac laptop and sample libraries running in Logic, and in many cases these virtual instrument tracks survived into the final mixes. “In all fairness, while I may describe my setup as not sophisticated, in reality a quad-core laptop slammed full of RAM, with terabyte hard drives and huge sound libraries going back 20 years and linked to great sample players, is hardly a small tool. It actually is a very powerful tool, and more than I could have imagined having at many other points in my career! I still use Logic 9, by the way, because I had some words with Apple over the direction they took with X, particularly when they showed me that they had put in things like ‘male vocal chain’, which had compression, EQ and reverb preset. I was like, ‘How can you possibly do this?’ How can anyone know what it will be used for and, second, why take away people’s option to learn how compressors work, and to experiment with them?’ It’s often the errors that people make that are the most interesting.”

Much of the music on Popular Problems was composed by Patrick Leonard using a Mac laptop and sample libraries running in Logic, and in many cases these virtual instrument tracks survived into the final mixes. “In all fairness, while I may describe my setup as not sophisticated, in reality a quad-core laptop slammed full of RAM, with terabyte hard drives and huge sound libraries going back 20 years and linked to great sample players, is hardly a small tool. It actually is a very powerful tool, and more than I could have imagined having at many other points in my career! I still use Logic 9, by the way, because I had some words with Apple over the direction they took with X, particularly when they showed me that they had put in things like ‘male vocal chain’, which had compression, EQ and reverb preset. I was like, ‘How can you possibly do this?’ How can anyone know what it will be used for and, second, why take away people’s option to learn how compressors work, and to experiment with them?’ It’s often the errors that people make that are the most interesting.”

Climbing Mount Cohen

“Writing the music to Leonard’s lyrics was a matter of contemplating and meditating on what it wants to be. Once you know what it wants to be, you can just do it. With some of these songs I was driving back to my house, and my phone would ring and there would be a new lyric. I would be reading it while driving, because it was impossible not to, and by the time I got home, I would know what to do, and I’d record it and send it to him. Sometimes he’d give me feedback, and say, ‘It’s not like that,’ and I would do another one, and that would be the one. Or there would be more versions. In some cases we didn’t make it, and we’re still working on these songs. We spent a lot of time at Leonard’s house trying ideas and putting them down, and trying to figure out the songs that are tough. ‘A Street’, for example, was a production challenge for me. It was written by Leonard and Anjani Thomas many years ago, and Leonard and I considerably reshaped it. I changed the feel to a blues shuffle and the structure by adding an interlude and putting the chorus chords at the end.

“The main two mountains we climbed with this record were ‘Born In Chains’ and ‘Nevermind’. To really find the centre of them was just luck. You can only do so many songs like that on a single project. The ones that aren’t that hard are still a lot of work, and the ones that are hard really take it out of you. Leonard wrote ‘Born In Chains’ many years ago and has spent a lot of time working on it. It was a real challenge to figure it out. We recorded a version of the song for Old Ideas, but we never got it. On this record we got it, but only barely. I wrote the song ‘Nevermind’ probably 10 times. I did all kinds of versions trying to get it right. I love that lyric! Finally, one day we were at his house, and I put up that quarter-note bass drum and a Fender Rhodes sound, and started playing that riff, and Leonard had his headphones on and did his thing, and it went straight down. We just improvised it. I added the other sampled parts — the strings, the organ, the djembe — immediately afterwards, in the moment. The main riff was played by me on a Fender Rhodes. The Middle-Eastern-sounding female vocal sample in the song comes from the EastWest Voices Of Passion sample collection. It was the first key I played, and Leonard liked it, so I just left it. It uses a different scale than the rest of the music, so isn’t quite harmonically right, but it somehow was OK, because the key centre is the same.

What’s Real

After Leonard had written the music for Popular Problems, in most cases at his log-cabin studio, and had recorded Cohen’s vocals at the poet and singer’s home studio, the producer brought the sessions back to his log cabin, where he and engineer Jesse E String overdubbed drums, bass, guitar and backing vocals.

Jesse E String and bassist Joe Ayoub at work in Patrick Leonard’s log-cabin studio in the mountains north of LA.

Jesse E String and bassist Joe Ayoub at work in Patrick Leonard’s log-cabin studio in the mountains north of LA.

“We’d accumulate several songs, and Leonard would learn to sing them,” Leonard elaborates, “and I then went over to his house where we’d sit for an afternoon. He’d do 10 takes of each song, and I’d take them back home, where Jesse and I would comp the vocals for each song. After that we invited the musicians in. Drummer Brian McLeod and bassist Joe Ayoub played on ‘Slow’, and James Harrah even played a guitar part, but we all listened to it, and concluded: ‘You know what, the demo that was done in half an hour sounds and feels better.’ Better is a qualitative judgement of course, because things are always better for a certain purpose. The curtains in this room are red, because that colour works well in this room. That does not mean that red is better than blue! And so my demo backing was a better fit for Leonard’s lyrics and vocals.

“Brian is one of the world’s best drummers, and there was an occasion when he had just replaced my sample drum part, and just as he came back in the studio Jesse and I had switched back to the sample part, for comparison. When Brian came in he said, ‘Oh, that sounds good,’ thinking it was him playing. When you can fool a great drummer into thinking that it’s him playing, that’s good enough for me! The fact that Brian plays a snare drum that has seen service during World War 1, all of these things that I used to get so hung up on, none of that matters any more. If a sound really fills the space and does what it is supposed to do, who cares where it came from?”

Drastically Different Demos

Jesse E String at Henson Studios in LA.Photo: Jeff SteinbergJesse E String (his real name, and he’s primarily a cellist, not a guitarist) has worked with Patrick Leonard since 2006, when he was a runner at Henson Recording Studios in LA, where Leonard had a recording space. String went freelance after Leonard left Henson in 2010, and he’s since worked on a wide variety of projects, being on call whenever Leonard needs him. During this past year String’s main preoccupations were recording Nick Jonas’s eponymously titled solo album and Popular Problems — “I don’t think you can get further apart in the musical spectrum,” he muses.

Jesse E String at Henson Studios in LA.Photo: Jeff SteinbergJesse E String (his real name, and he’s primarily a cellist, not a guitarist) has worked with Patrick Leonard since 2006, when he was a runner at Henson Recording Studios in LA, where Leonard had a recording space. String went freelance after Leonard left Henson in 2010, and he’s since worked on a wide variety of projects, being on call whenever Leonard needs him. During this past year String’s main preoccupations were recording Nick Jonas’s eponymously titled solo album and Popular Problems — “I don’t think you can get further apart in the musical spectrum,” he muses.

String also has an engineering credit on Old Ideas, but adds that he “didn’t do much on that record, just some vocal comps with Pat[rick]. Leonard didn’t want many outside people, and Ed Sanders mixed most of the songs, while Pat mixed his own songs in Logic. I think Ed and Pat mixed one of Pat’s songs together. Leonard often falls in love with the demos that Pat makes in Logic and so they were used for the final versions. With Popular Problems Leonard gave Pat a lot more space to do what he does, and while there were very few real musicians on Old Ideas, we fleshed out almost all the songs on Popular Problems with a band. On some songs this didn’t work, like on ‘Slow’, because Pat’s demo actually sounded better than the versions we did with the live musicians. Because Leonard likes Pat’s demos so much, when Brian and Joe came in to play drums and bass they generally tried to play the parts that Pat had written, almost note for note. We also were sonically trying to match their sounds to the demo, because if it sounded drastically different Leonard would ask: ‘What happened?’ But on the song ‘Samson In New Orleans’ Brian and Joe significantly changed the feel of the rhythm section and played in more places than Pat had done. Leonard loved it, which was great for us, because it gave Pat and I the feeling that we had more of a free rein in using the live musicians.”

47 Varieties

One challenge for Jesse E String was getting the most comfortable vocal performance from Cohen. “The microphone changed, because Pat started off using his [Neumann] U47, which he had used for Leonard’s vocals on Old Ideas as well. Pat’s 47 is one of the best mics I have ever heard, it’s amazing! But during the recordings for Popular Problems Leonard started getting uncomfortable with the mic, and said he wanted a handheld mic, so Pat recorded Leonard’s vocals for ‘Born In Chains’ with a Shure SM58. If you listen you can hear it’s a different mic. I then suggested to Pat that Leonard use a Neumann KMS105, which is a really nice handheld mic, and Leonard did a few songs with that, which was a vast improvement. Eventually Patrick worked out that Leonard actually preferred to sit while singing, and then they went back to using the 47. I recorded Leonard’s vocals on ‘Almost Like The Blues’ and ‘Did I Ever Love You’ at Ed’s place, using Pat’s 47 and an AMS/Neve 500-series mic pre. I did not use compression, and I don’t think Pat did either for the vocals recorded at Leonard’s place.

“So there was a bit of a merry-go-round with Leonard’s vocal mic, and we had a bit of the same with Logic and Pro Tools, because while I know my way around Logic, I prefer to work in Pro Tools. When Pat came back from Leonard’s place for the vocal comp I’d mix the music to two tracks and I’d export that and Leonard’s vocal takes to Pro Tools. After Pat and I had comped the vocals, I consolidated everything, and I’d then transfer the vocal comp back to the original Logic session, so Pat could show it to Leonard, and could also still make changes to the music if he wanted. There were some songs on which we recorded bass and drums before Leonard had laid down his vocals, and these were bounced to Logic so Pat could record Leonard over them. Conversely, before I recorded anyone on Pat’s demos, I always bounced the tracks from Logic to Pro Tools. So there was a slow migration from Logic to Pro Tools. Everything was in 44.1kHz/24-bit, because that’s what Pat was using in Logic.

“We did a rhythm-section recording session with Brian and Joe together, which was the extent of people actually playing together on this album. We also did sessions with Brian and Joe separately. My recording chains couldn’t be simpler. On the drums I had a Sennheiser MD421 on the kick, an AKG C414 on the snare, a Shure SM7 on the ride, a Shure SM57 on the hi-hat, and two B&K 411’s in the room for ambience. I ran all these mics through several of Pat’s Neve 1073s and then straight into his Pro Tools HD system. There was no processing apart from a little bit of EQ on the 1073s. I had a Neumann M149 on Joe’s double bass, going into a Neve 1073, with some surgical EQ ducking in the 300-400Hz range, and I ran it through Pat’s LA2A. For the acoustic guitar I used a Neumann KM84, and the electric guitar cabinet was recorded with an MD421, and both went through a 1073 and an 1176. The background vocals were recorded with Pat’s Telefunken ELAM 251, going through a 1073 and then an LA2A. The violin was recorded later, at Ed’s studio, with a Flea 49 mic and going through an API mic pre and straight into Pro Tools. For me the signal chains start before the microphones, and Alex’s violin tone was superb and the recorded sound one of the best I’ve ever tracked. The engineering on this record really matched the minimalist approach of the production. It was all very clean.”

Record Fast, Mix Slow

After a lightning-fast writing process and a more steady overdubbing stage, Leonard and String arrived at Ed Sanders’ studio for a drawn-out process of mixing and adding further recordings. This took from June 11 to July 22 this year, with Sanders also present to provide a listening ear and general support. Leonard recalls, “Ed’s studio is in downtown LA, which was convenient for Leonard. He’s also familiar with the space, so we ended up there and it worked really well. The mixing went on for quite a while because we started making small musical additions and changes, and because we decided to leave some songs off, I wrote an additional song, ‘Almost Like The Blues’. Leonard sent me the lyric, and I did one version, which he didn’t like, so I did another, and that is what you hear on the album. I wrote that sitting at a kitchen table with a laptop and headphones! Leonard overdubbed his vocal at Ed’s place, and he also re-sang his vocal to ‘Did I Ever Love You’, and we added the violin and some more backing vocals. Rather than describing this as a mixing phase it’s more correct to say that we finished the album there.”

“I’ve never understood the current situation,” adds String, “in which people finish their recording project and then send it over to one of the many boutique mixers to mix it. I can see the benefit of someone coming in with fresh ears towards the end of a project, but for me the mixing stage is still very strongly also a production stage. I’ve never thought, ‘Now we just mix it and it’s done.’ It is during mixing that the tracks come really alive and at that point you gain new perspectives and you often want to change things, like record a new vocal or instrument. It has always been like that in working with Patrick, where mixing is in fact the last stage of production. It’s not only a final polishing stage. The way Pat and I work is that we are always constantly mixing while we record, and during the mixing stage we figure out how everything works. I would say that when we start to mix, we’re not really ready to mix in the traditional sense. We’re ready to decide what works and what doesn’t work. It’s a continuous process, and for this reason there isn’t a set mix routine.

“In doing Popular Problems, we were switching between songs all the time, so the ability to recall was crucial, otherwise it would have been a nightmare. I was mixing through Ed’s Harrison desk, but only used it for analogue summing. The Pro Tools session came up on nine or 10 faders on the board, and from there the stereo mix went back into the session. The only mix routine we had was that I’d say, ‘Give me a couple of hours with this,’ and I would pull up the session, and I’d take it to where I thought it sounded good. It wouldn’t take too long, because none of the sessions had many tracks. I’d then get feedback, first from Pat and Ed, and later from Leonard. He would either say, ‘You missed it, it’s not on the mark,’ or ‘There are a couple of issues,’ or ‘Perfect, don’t touch it.’ But if the latter was the case, we still went back and touched it. I don’t think there was one mix to which we didn’t return to tweak more things at a later stage. We agonised over every mix.”

The Music Comes Second

“The bottom line with this record is that it is all about Leonard’s voice, and we didn’t want anything to distract from that. Leonard once told Pat, ‘You know what I love about those old 45s? There was the singer, and then there was all this stuff behind them.’ That kind of became our mantra during the mixing stage. If you listen to the end result, it’s like that: it’s Leonard and all the stuff behind him. With Leonard’s vocal so far up-front, we didn’t need much compression on the music to make sure things fit in a dynamic range. The drums were never going to be rock & roll in-your-face. We went for a very natural sound, and we let the transients fly. With a rock or pop track, you start with the drums, and then you add the bass, and then you work your way up from there. This was not like that at all. It was a matter of getting the vocal loud and then push up all the stuff behind it. I would start with Leonard’s vocals, and I’d then add the other tracks one by one.

“It was never a struggle for me to balance Leonard’s voice against the music, because I was cutting so much low end out of the bass. The low end would have been too big otherwise. We were going for a bass reminiscent of John Paul Jones in Led Zeppelin, a Precision bass that’s much more in the lower mid-range. Modern records have this huge low end, and we wanted to stay away from that. The only thing that was a bit of a struggle with Leonard’s voice was the setting of the high-pass filter. Normally setting that on a vocal is not a big deal: you set it to 100Hz to take the room and extraneous noises made by the singer out and that’s it. But on Leonard’s voice we needed to be really precise — 5Hz lower or higher made a real difference. This was the only record I’ve ever worked on where the high-pass was a key element of the vocal sound. Leonard sings so softly that there are loads of ambient noises, and so close to the microphone that there’s a huge proximity effect. Without the high-pass filter we would have blown out everyone’s subwoofers. For most songs the high-pass filter on his voice was in the region of 75Hz, and on ‘Samson In New Orleans’ it was set as low as 54Hz!”

‘Slow’

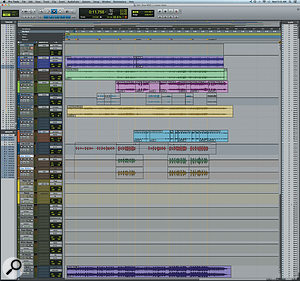

This composite screen capture shows the minimalist Pro Tools session for ‘Slow’.‘Slow’ is a tiny session by modern standards, with just six stereo music tracks — kick, Motown bass, three keyboard parts, a horn section part — and three mono vocal tracks: Cohen’s and two backing vocals. In addition there’s a click track at the top of the session, two reverb aux tracks, five master tracks (drums, bass, keys, backing vocals and effects), and one mixdown track. This adds up to a grand total of 18 tracks, with just 11 plug-ins on them. In Cohen’s universe, it’s not only slowly that does it, but also simply.

This composite screen capture shows the minimalist Pro Tools session for ‘Slow’.‘Slow’ is a tiny session by modern standards, with just six stereo music tracks — kick, Motown bass, three keyboard parts, a horn section part — and three mono vocal tracks: Cohen’s and two backing vocals. In addition there’s a click track at the top of the session, two reverb aux tracks, five master tracks (drums, bass, keys, backing vocals and effects), and one mixdown track. This adds up to a grand total of 18 tracks, with just 11 plug-ins on them. In Cohen’s universe, it’s not only slowly that does it, but also simply.

As the most important element in the mixes, Cohen’s voice was the only one that went through an analogue treatment chain, and proved so challenging that String and Leonard had to call in the mix emergency services right at the end of the project in the shape of studio legend Bill Bottrell, who spent a day fine-tuning mostly the vocals.

“I had Leonard’s vocal track coming up on one channel on the desk,” says String, “and ran it through a Dbx 160X compressor and a Mercury EQH1 EQ, which is very nice and well-built. We initially tried Ed’s Bricasti for reverb on his vocals and the backing vocals, but we eventually favoured the Altiverb ‘Wendy Carlos plate’. The ‘Room’ aux reverb had the Altiverb room plate, from Cello Studio A, which I used on the keyboard and horn tracks. The FabFilter Pro-Q is my favourite plug-in EQ, and I used that on the kick, the bass, and all the keyboard tracks. One of the challenges with this mix was the kick level, which started bothering Leonard at some point, because he felt it was stepping on his vocal. In the end the kick sounds like a pillow being hit, because we rolled off everything below 75Hz and everything above 1k. It looks pretty funny in the screenshot! Wherever the high-pass on Leonard’s voice was set determined where the kick was going to be. There’s an empty Fender Rhodes track, because I sent the sampled Rhodes out to an amp and reprinted it. The horns have the McDSP Analogue Channel, because the track was sounding a bit too synthy to me, and I wanted to warm it up a bit. It saturates the sound in a nice way. Finally, I had the McDSP Compressor Bank on the backing vocals to keep them in place.”

‘Samson In New Orleans’

‘Samson In New Orleans’ was, by contrast with ‘Slow’, a slightly busier mix, thanks to the addition of ‘real’ instruments. Five master bus tracks have been removed from this shot for space reasons.‘Samson In New Orleans’ is one of the five tracks with live musician overdubs on Popular Problems: in this case bass, drums and violin. For this reason the session is larger than that of ‘Slow’, but it’s still a modest 25 audio tracks plus three aux tracks, five master tracks, and finally the mixdown track, totalling 34 tracks in total. The audio tracks break down into five live drum tracks, three programmed drum tracks, a bass, sampled French horns and trombones, the live violin track, Leonard’s electric piano, Cohen’s vocal track and 11 backing vocal tracks, while the three aux tracks are all reverbs.

‘Samson In New Orleans’ was, by contrast with ‘Slow’, a slightly busier mix, thanks to the addition of ‘real’ instruments. Five master bus tracks have been removed from this shot for space reasons.‘Samson In New Orleans’ is one of the five tracks with live musician overdubs on Popular Problems: in this case bass, drums and violin. For this reason the session is larger than that of ‘Slow’, but it’s still a modest 25 audio tracks plus three aux tracks, five master tracks, and finally the mixdown track, totalling 34 tracks in total. The audio tracks break down into five live drum tracks, three programmed drum tracks, a bass, sampled French horns and trombones, the live violin track, Leonard’s electric piano, Cohen’s vocal track and 11 backing vocal tracks, while the three aux tracks are all reverbs.

String explains: “This was one of the easiest tracks to mix. It was the one out of all of them where Leonard said it was incredible. His compliment was so good that it left me ecstatic for the entire weekend afterwards! But other than that this mix isn’t that different from the others. Once again, there aren’t many plug-ins: mixing was much more a subtractive process than anything else. Everything sounded great the way it was recorded, so basically we had to judge whether anything got in the way of the vocal, and if it did, make adjustments. But there never was any high-level processing. I had compression from the Compressor Bank on the backing vocals and also on the upright bass, in fact quite a bit on the latter, because it has so little sustain, and I squashed it to give it a more consistent tone. The rest was subtractive EQ and reverb.

“The drums have the Waves Renaissance EQ, because you can’t run native plug-ins in Pro Tools when you’re recording, and I only had the native version of the Pro-Q, so I used the REQ instead. It’s our input EQ. I didn’t have a problem with how it sounded afterwards, so I left it. The violin has some Avid 7-band EQ, which is there for the same reason that I had the Renaissance EQ on the drums. It’s just a high-pass and it does a slight dip of 2.2dB at 1kHz, and that’s it. The Compressor Bank on the violin does not go past 3dB, it’s very subtle. The green track is the electric piano, which I ran re-amped, to give it a bit more air. Leonard’s vocals would have had the same signal chain as on ‘Slow’, with the Dbx 160X and the Mercury EQ1H, and a Pro-Q. I also gated all Leonard’s vocals, so that the track ducked the moment he stopped singing, to get rid of extraneous noises. The funniest example of that is at the end of the very last line he sings on the last song on the album, ‘You Got Me Singing’, where you can hear the sound of a dog barking in the background, from across the street. It was in time and in tune, so we left it! We did Charlean Carmon’s chorus vocals in three parts, left and right and centre, and I used an Altiverb reverb with a 20-second decay for a cool, washed-out and otherworldly effect. It was one of the few times we didn’t do something that was plain and simple.” One of the biggest challenges in mixing Popular Problems was keeping low-end instruments out of the way of Leonard Cohen’s voice. That resulted in EQ settings like this, from the bass on ‘Samson In New Orleans’.

One of the biggest challenges in mixing Popular Problems was keeping low-end instruments out of the way of Leonard Cohen’s voice. That resulted in EQ settings like this, from the bass on ‘Samson In New Orleans’.

The Third Master

Eagle-eyed perusers of the screenshots will, however, have noticed the absence of plug-ins on Leonard’s vocals and the Plate 140 aux track in both sessions. Apparently this was the result of Bill Bottrell’s last-minute mix tweaks. String explains: “What happened was that we had done all the mixes, running them back into Pro Tools through Pat’s Neve 2254, and we went for a first mastering session, and we were very pleased with the result. When you listened to each song individually, they each sounded fantastic. But Leonard was the first to notice that when you listened to them all together, the vocal levels were jumping a little. We realised that we had to re-examine where the vocal had to sit on the album as a whole. Because the vocal was so loud in comparison to the music, the issue hadn’t really come to light.

“After we had spent a day resetting the levels and making sure that all the vocal levels and the relationships between the vocals and the music were the same, we went back for another mastering session, with Stephen Marcussen. We felt that it sounded much better, but Leonard said that it still wasn’t quite right. I think he felt that his vocal sound was a little in peril. At this stage Pat called in the Big Gun, Bill Bottrell, who is one of my all-time idols, so I was more than happy for him to come in.”

Bill Bottrell is a living legend of the American music industry, who has worked with Michael Jackson, ELO, Madonna, Sheryl Crow and many more, but now lives in semi-retirement in Northern California. Bottrell added another 40 years of recording experience to the Leonards’ combined 91, and in so doing he helped them get close to perfection in realising their purpose. “Bill basically left the music tracks the same, and treated Leonard’s vocal slightly differently,” continues String. “We had realised that Leonard loves the sound of his vocal through an old limiter called a Western Electric, which looks like something you hook up to a car. We had tried it during the mixing stage, but Pat and I weren’t too keen on it. But Bill sent Leonard’s vocal through the Western Electric, did some EQ’ing, and the other main thing he did was change the reverb on Leonard’s vocal to a Universal Audio EMT 140 plate plug-in. He also used reverb a bit more generously than we had done. Right from the moment when Bill was making these changes, Leonard was really happy.”

Patrick Leonard concludes: “You could say that we lost our objectivity a bit at the end of what had been a five-month-long process. I don’t think there’s anyone I trust more than Bill, he’s the greatest, and he went through all the songs in one day and that was enough. After this Leonard was entirely happy, and we went back for a third mastering session with Stephen, and we were done.”

“I never liked it fast, with me it’s got to last,” sings Cohen in ‘Slow’. In Popular Problems, the Leonards, with help from String, have created an album that is sure to do the latter.

The Other Leonard

The coincidence of the two main protagonists on Popular Problems sharing a name is the subject of good humour between Leonard Cohen and Patrick Leonard. The latter recalls one such instance. “I was driving to Leonard’s studio one day when I passed a white truck that had ‘The Leonards’ written on its side, and nothing else, so I had no idea what business they were in. When I got to Leonard’s house we were joking about it, and we had the idea of billing ourselves as ‘The Leonards: 100 years of recorded music.’ Because between the two of us, we have 100 years of experience in recording! When we work together, what we are really doing is trying to distil that experience as best as we can, and be as economical as possible in writing, performing, and production. Leonard comes up with phrases that will go through you like a screaming army. I aspire to that, but I know I don’t have in me what he has. What I can do is distil all my knowledge of music into a single drop, with each note being the right one.”

A pedant might point out that the Leonards ‘only’ have 91 years of recorded music between them: Cohen’s debut album, Songs Of Leonard Cohen, was recorded and released in 1967, and Patrick Leonard’s recording career started in 1970, when he played, at the tender age of 14, on a long-forgotten album by an obscure Chicago band produced by Larry Carlton. Ninety-one years in recording studios is impressive by any standard, and the shared experience and talent that the Leonards distilled into Popular Problems has contributed to the album topping the charts in many countries around the world and receiving countless rave reviews.

Originally from a sparsely populated peninsula north of Lake Michigan, Patrick Leonard came to prominence in 1984 when he was invited to play keyboards on the Jacksons’ Victory tour. His talents were so evident that he was quickly promoted to the tour’s musical director. Madonna subsequently headhunted him as musical director on her 1985 Virgin tour, leading to an extraordinarily fruitful collaboration which saw Leonard co-write many of the pop star’s classic songs on albums like True Blue (1986), Like A Prayer (1989) and Ray Of Light (1998). He would go on to work with luminaries like Bryan Ferry, Rod Stewart, Pink Floyd, Roger Waters, Elton John, and Bon Jovi.

It’s a heavy-duty list of credits by any standard, but during the last 10 years Leonard has gradually withdrawn from high-profile mainstream work, because of changes in the way the music industry works, with record companies increasingly taking control of artists’ artistic directions. “I can’t do things I don’t like. I would rather drive a Toyota for the rest of my life,” comments Leonard. He remained busy composing and working on independent musical theatre, film and general story ideas, but a few years ago he was coaxed by Leonard Cohen’s son Adam into producing the latter’s 2012 album Like A Man. The younger Cohen was eager for Patrick Leonard to work with his father, so the older duo collaborated on four songs on Cohen’s 2012 album Old Ideas and two years later on the whole of Popular Problems.

Samples: It Doesn’t Matter What People Think

“The vocal sample in ‘Nevermind’ is one of those things that I would never have been able to accept in my younger years without first going into a screaming hissy fit,” says Patrick Leonard. “Here is what I have come to, and it may sound crazy, but I am going to stand by it: I’ve come to a place where I don’t care any more whether people think something is a sample, or not. It’s kind of embarrassing, because if you look at my studio, you’ll see an old Steinway B, a Yamaha CX7, a beautiful Fender Rhodes, a great Wurlitzer, a great Hammond B3, a Prophet 5, a Minimoog, all the badass keyboards you can think of. And yet on this record I used none of them! The keyboards, strings and horns, and also the drums and bass in four songs, are all samples. The organ is a Native Instruments B3 sample, the electric piano a MOTU Mach V sample, and so on.

“This is in part the result of something Leonard said to me when working on Old Ideas. I was writing a cello part and playing it with a sample, and I said to Leonard: ‘This will sound great when it is played on a real instrument.’ And Leonard replied, ‘I have news for you, because what you’re playing is real instrument. You push a key, and a sound comes out. That’s an instrument.’

“On this album we had a violinist come in to play on a few songs, and I’m glad we did, because it does sound better than the sampled violin. But Leonard pointed out that my performance in some cases was better, not because it sounded more like an actual violin, but because of the feel. So I now think that musicality is what’s most important, and I am much more focused on that.

“Of course it depends on the context, but if I had used a real B3 on this album and had insisted on ‘real’ musicians, and we’d spent a lot of time getting the performances really right, I’m not sure it would have made a better album. And so the backing of four of the songs on the album is just me playing all the parts. The one thing I have to say about it is that there are no loops in any of the songs. All my parts were played through from top to bottom. My drums are from Toontrack Superior Drummer, and I might mess with the samples a bit, changing the ambience or the pitch, pressing whatever button I can find. After that I’d play them on the keyboard, from the beginning to the end of the song, and might quantise 40 percent or so not to make it too stiff, and that’s the drum part done. For the bass sounds I often used the Virtual Ensemble’s Trilogy ‘soul bass’ sample.”

The blurring of the lines between real and sampled instruments reached its logical conclusion on another of Leonard’s recent projects: “I’m currently working with Iris Hond, a Dutch concert pianist, on a newly composed ‘classical’ music project, and we wrote these demos using Vienna string samples and the piano at her home, and some voice samples. We then recorded a version of that at EastWest Studios in LA, with a 25-piece orchestra, a brand-new concert grand piano tweaked by one of the best piano techs in the world, and a wonderful singer doing all the voices. Afterwards we were listening to this, and could not tell the difference between the two recordings!”

Leonard is, however, careful to point out that the shift away from traditional instruments does not invalidate the need for musicality on behalf of the performer. “You simply don’t want to hear me talk about what technology has done to the level of music and musicianship and performance, because it is really depressing. There is no up side. It’s not just that things have gone backwards, we have never been in a position where there is such a global reach for so much garbage! The counter-argument is that it’s great that there’s so much music available for everyone, but there just aren’t 100,000, or whatever the number is, supremely gifted people around. There just aren’t!”