In 1973, a band from Florida and California went to a studio in Georgia to record a song, provoked by a Canadian, about Alabama - and managed to define the sound of Southern rock while they were at it.

Lynyrd Skynyrd in 1973. From left to right; Leon Wilkeson, Billy Powell, Ronnie Van Zant, Gary Rossington, Bob Burns, Allen Collins and Ed King.Photo: GEMS/RedfernsThe quintessential Southern rock band, Lynryd Skynyrd not only performed some of the grittiest, most uncompromising blues-driven music of the '70s, but thanks to the songwriting of frontman Ronnie Van Zant and the hard-living, good ol' boy image of its members, also established themselves as the archetypal proponents of Southern pride and defiance. After all, if Neil Young had the nerve to use numbers such as 1970's 'Southern Man' and 1972's 'Alabama' to portray many Southerners as a bunch of Klan-loving, banjo-playing hicks who needed to forgo lynchings in favour of civil rights, then Van Zant certainly had the balls to respond.

Lynyrd Skynyrd in 1973. From left to right; Leon Wilkeson, Billy Powell, Ronnie Van Zant, Gary Rossington, Bob Burns, Allen Collins and Ed King.Photo: GEMS/RedfernsThe quintessential Southern rock band, Lynryd Skynyrd not only performed some of the grittiest, most uncompromising blues-driven music of the '70s, but thanks to the songwriting of frontman Ronnie Van Zant and the hard-living, good ol' boy image of its members, also established themselves as the archetypal proponents of Southern pride and defiance. After all, if Neil Young had the nerve to use numbers such as 1970's 'Southern Man' and 1972's 'Alabama' to portray many Southerners as a bunch of Klan-loving, banjo-playing hicks who needed to forgo lynchings in favour of civil rights, then Van Zant certainly had the balls to respond.

"Well, I heard Mister Young sing about her," he intoned on 'Sweet Home Alabama', the opening track on Skynyrd's 1974 Second Helping LP. "I heard ol' Neil put her down. Well I hope Neil Young will remember, a Southern man don't need him around, anyhow."

Although the song served as both a celebration and a vindication of the 'Yellowhammer State', the irony is that neither Van Zant nor his two fellow composers were originally from Alalabama. He and band co-founder/guitarist Gary Rossington were born in Jacksonville, Florida, while guitarist Ed King was from Glendale, California. 'Sweet Home Alabama' was, nevertheless, a top 10 hit in the US, and has subsequently become a staple on AOR radio stations, while in 2006 Country Music Television voted it number one among the 20 Greatest Southern Rock Songs.

Studio One

The group themselves first came to prominence with the release of their 1973 debut album, Pronounced Leh-Nerd Skin-Nerd. Produced by Al Kooper, who had signed the band to MCA the year before, this included 'Freebird' and featured the three-pronged guitar line-up of Rossington, King and Allen Collins, together with Bob Burns on drums, Leon Wilkeson playing bass and keyboardist Billy Powell. The same personnel then reassembled for 'Sweet Home Alabama', again with Kooper sitting behind the console at Studio One, a facility located in the Northern Atlanta suburb of Doraville, Georgia, that had been designed and constructed by engineer Rodney Mills, with assistance from music publisher Bill Lowery and future Altlanta Rhythm Section manager Buddy Buie.

Photo: GEMS/RedfernsA former bass guitarist with a Georgia outfit named the Bushmen, Mills became the chief engineer at Atlanta's Lefevre Sound Studios in 1968 and recorded a wide variety of rock, R&B, country and gospel acts, including Joe South, James Brown, Billy Joe Royal and the Stamps Quartet. Then, in 1970, Buddy Buie commissioned him to design and oversee the construction of Studio One, and Mills remained there for the next 16 years, engineering and/or producing records by, among others, BJ Thomas, the Outlaws, Journey, Johnny Van Zant, the Atlanta Rhythm Section, 38 Special and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Photo: GEMS/RedfernsA former bass guitarist with a Georgia outfit named the Bushmen, Mills became the chief engineer at Atlanta's Lefevre Sound Studios in 1968 and recorded a wide variety of rock, R&B, country and gospel acts, including Joe South, James Brown, Billy Joe Royal and the Stamps Quartet. Then, in 1970, Buddy Buie commissioned him to design and oversee the construction of Studio One, and Mills remained there for the next 16 years, engineering and/or producing records by, among others, BJ Thomas, the Outlaws, Journey, Johnny Van Zant, the Atlanta Rhythm Section, 38 Special and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

"The setup at the time of the first Skynyrd album included a Spectrasonics four-bus custom console made by a company out of Louisville, Kentucky," Mills recalls. "It had a 16-channel monitoring section and was primarily designed for 16-track, which was the highest multitrack then available. It was a discrete console, with all of the sections divided independent of each other, and the monitor section was laid out to the side instead of in-line, as it would become later on. We did not have a lot of discretion in terms of the EQ — the EQs had three sections on the low end, and there were three frequencies available on the high end. There was no mid-range EQ. The control monitoring section was strictly a level and pan, and that was it. You couldn't add any effects to playback at all.

"The console sounded pretty good for those days, although the only other one I had worked on at that point was the custom-made four-bus console at Lefevre Sound, which had Langevin equalisers and an eight-track capacity. When we built Studio One, that was eight-track as well, and we then switched to 16-track and used a Scully 100 two-inch tape machine, which was a low-economy model. For monitors we had JBL 4320s, which each had a single 15-inch woofer with a mid-range horn, as well as a compression tweeter that I added, and there were also some small Auratones sitting on the console."

As designed by Mills and Buie, Studio One's live room was V-shaped, with the pointed end at the front and a rear section that widened into a rectangle. Total length from front to back was about 50 feet. The live area wrapped around the control room 'V' and was about 10 feet wide on either side, with a length of 30 feet from the tip of the 'V' to the end of the live area. The console was positioned towards the front of the control room, and the monitors were on either side, suspended from the ceiling and angled inwards. By 1974, those speakers were placed inside specially constructed soffits.

"The way Buddy primarily liked to work was to have the musicians around him," Mills explains. "The console was therefore placed as far forward as possible in the control room, so that we could see the guys on either side out in the studio. That worked OK part of the time; since the majority of the flooring in the control room was elevated, we could set up a little higher than the musicians and see them better. However, most of the time the guitar players and bass players would all sit in the control room and have their amps in the studio on either side of that 'V'. The 'V' itself was all glass, but we didn't let stuff like monitoring and reflections get in our way! I wound up putting curtains over those windows to cut down on some of the reflection, but that was it."

Mic Selection For 'Sweet Home Alabama'

Vocals:

- Neumann U87

- AKG C414

- Beyer M500

Guitars (electric):

- Shure SM53

- Sennheiser MD421 & MD451

- Neumann U87

Guitars (acoustic):

- AKG C414

Bass:

- Neumann U87 & DI

Organ:

- Electrovoice RE20 (bottom)

- AKG C451 (top)

Piano:

- Neumann U87 (low strings)

- AKG C451 (high strings)

Drums:

- Shure SM56 (snare)

- Electrovoice RE20 (kick)

- Neumann KMR81 (hi-hat)

- Sennheiser MD421 (toms)

- Neumann U87 (floor tom)

- AKG C451s (overheads)

Leh-Nerd Skin-Nerd

While Rodney Mills recorded a small amount of Lynyrd Skynyrd's first album, including the basic track of 'Tuesday's Gone' and guitar overdubs on 'Freebird', he was also involved with another project, so the assignment mainly went to Studio One's other in-house engineer, Bob Langford.

"There was only one room, and we worked that studio day and night," says Mills. "If you wanted to cut in there, you could take the day shift or the night shift. There were no strict hours, so the only way of doing two projects at one time was for one of them to run from, say, 11 in the morning to seven in the evening, and then for the other to run all the way through the night until the next morning. That's how it worked with Skynyrd on the first album, and after it was completed the band came up with a new song and decided to go back into the studio to record it because they thought it might be strong enough to hold up the album's release."

That song was 'Sweet Home Alabama', and although it didn't end up being included on the first album, it was in the can before the commencement of sessions for Second Helping. And on hand to take care of the engineering was Rodney Mills.

"Everyone had been raving about the song when they saw them play live around Atlanta, so when they came in to record it, I kind of jumped at the chance," he explains. "The studio was booked for just one day, so the entire track was recorded in that time, except for the backing vocals by the Sweet Inspirations, which were done in California, where the song was also mixed."

According to Ed King, it was actually following a band rehearsal in the late summer of 1973 that, inspired by a Gary Rossington guitar riff, he went to bed and the chords and two main solos for 'Sweet Home Alabama' came to him, note for note, in a dream. King presented the new tune to the other band members the very next day, and Ronnie Van Zant, who felt that Neil Young's criticisms of Southern social conditions amounted to "shooting all the ducks in order to kill one or two," subsequently came up with lyrics that caused their own controversy by referencing Watergate and pro-segregation Governor George Wallace.

The Vampire Drum Box

"The basic track was recorded with just Ed King, Leon Wilkeson and Bob Burns," recalls Rodney Mills. "In those days, if you could hear ambience on the drums, you were doing something really bad, so we had built a drum booth that was so dead it would suck the life out of anything that entered it. Basically, it was just a big, rectangular room, constructed with a stud floor system, multiple layers of plywood on top, and fibreglass stuffed in between the floor joists, as well as behind the burlap walls and ceiling. There was just one little ventilation hole and no air conditioning, so a drummer could work for about 20 to 30 minutes before a plea for oxygen would make us take a break.

"You see, we did have an electric fan in there to circulate a little air, but whenever we started recording we'd have to cut the fan off. That meant it was good enough to do about three takes before we had to change the tape reels, and that also gave the drummer a chance to come up for air, put the fan on and step outside for a minute. So, while it wasn't a terrible inconvenience for us, it was not good on the drummer, especially since the booth itself was bright red inside. I don't know what we were thinking.

"That thing must have weighed a couple of tons, but we put it on wheels so that we could just roll the booth up close to the control room. Normally, however, it sat in the back right-hand corner of the studio, and that's where it was for the recording of 'Sweet Home Alabama'. It was about large enough to get a set of drums in there, so we built a 'snout' at the front to house the kick drum. That meant the drummer could move his kit forward and see a little better out of the tiny one foot by three foot window just above the snout, but it was absolutely awful.

"It was not tall, about eight feet high at the most, and about 12 feet wide and eight feet deep, with another three feet for the snout. The whole thing back then was to control the drums and not let them speak out as far as ambience was concerned. We would tape the snare, put wallets on it, treat the toms to remove any overtones, and do everything we could to make the drums as dead as possible.

"We couldn't have the toms ring out every time the drummer hit the kick. So part of it was about convenience, part of it was the sound of the time, and we weren't looking for drums to have ambience, unless it was a bit of manufactured reverb or room sound that we could control. Back then, we had an 'echo room', as we called it, built out of cinder-block and painted with epoxy paint, and we'd put a speaker and microphone in there. That's what we used if we wanted to create any extra ambience, along with an EMT plate."

Tracking

"Outside of that drum booth, the rest of the studio was totally ambient, which was totally crazy. It was as if, once the drums were isolated, everything else would just take care of themselves. We'd put gobos around acoustic pianos, but the rest of the room was pretty live, and that was a boon later on when we did finally free the drums and take them out of the booth. Of course, the idea was for that thing to be mobile, but it weighed so much that it took six people to move it. So it basically stayed in just that one position.

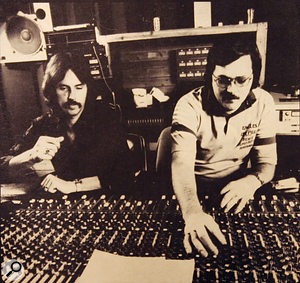

Although of an Alanta Rhythm Section session in 1970, this photo shows the unique layout of the Studio One live room and control room. To the left of the picture is the 'mobile' drum booth.Photo: GEMS/Redferns"When I recorded Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Burns was miked with an Electrovoice RE20 inside the kick drum, a Shure SM56 on the snare, Sennheiser 421s on the toms, a Neumann 81 on the hi-hat and AKG 451s for the overheads. While the kick and snare were on their own tracks, the toms, hi-hat and overheads were combined on two tracks. So we could get the kit on four tracks, and just by riding the toms and cymbals up and down in the mix I could semi-control everything."

Although of an Alanta Rhythm Section session in 1970, this photo shows the unique layout of the Studio One live room and control room. To the left of the picture is the 'mobile' drum booth.Photo: GEMS/Redferns"When I recorded Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Burns was miked with an Electrovoice RE20 inside the kick drum, a Shure SM56 on the snare, Sennheiser 421s on the toms, a Neumann 81 on the hi-hat and AKG 451s for the overheads. While the kick and snare were on their own tracks, the toms, hi-hat and overheads were combined on two tracks. So we could get the kit on four tracks, and just by riding the toms and cymbals up and down in the mix I could semi-control everything."

Looking through the control-room glass, Leon Wilkeson played bass to the right, using both a DI and an amp miked with a Neumann U87, combined onto one track.

"We only had one RE20, and usually I'd put that on the kick drum," says Mills. "However, if it wasn't being used on the kick, I would use it on the bass."

To the left of the control room, Ed King played the song's signature guitar lick on a late-'60s Fender Strat that went through a Fender Twin amp, also miked with a U87.

"Because the rhythm part was not exceptionally loud, I padded the microphone down and put it close to the cabinet," Mills remarks. "That was it; just one mic."

Formerly a guitarist with the Strawberry Alarm Clock, King had filled in on bass for Skynyrd's first album when Wilkeson surprised his bandmates by quitting shortly before those sessions began. Nonetheless, Van Zant was reportedly none too impressed with King's bass playing, so when Wilkeson rejoined, King returned to doing what he did best, playing rhythm guitar on the basic track of 'Sweet Home Alabama', and later adding the solo.

"Ronnie Van Zant also sang a scratch vocal when the basic track was recorded," Mills recalls. "At that point, I hadn't yet built a vocal booth that he could stand in, so he was in the room with the other three guys. I put up a couple of gobos, and since I miked him with an 87 for the final vocal I think that mic was already set up when he did the scratch track.

"We only did a few takes of the basic track. The guys were very familiar with the song, they had played it live since they had written it, and they were known for doing that with much of their material before they recorded it. So when they came to the studio they were prepared, and we probably did only three or four takes of that song. Also, Ed King's first attempt at the long solo was the one that you hear on the record. The band members were in the control room when he did that, and at the end they pretty much fell on the floor; they were just knocked out. However, Al Kooper thought there was something wrong with it. He wanted Ed to do another solo, so that's what Ed did and I guess it was put on another track, but to the best of my knowledge the solo that was used was the very first one that he did. That's what Ed remembers and that's what I remember."

In interviews, King has also stated that, since his Strat had bad pickups, he was forced to crank up the volume on his amp. "His Fender Twin was on the left-hand side of the control room," Mills confirms, "and he had to turn it almost wide open to get any sustain."

Ad Libs & Overdubs

While Allen Collins and Gary Rossington each overdubbed rhythm guitars going through Marshall amps, Billy Powell added a piano part that Rodney Mills now describes as "one of the great rock & roll keyboard performances. Considering it was a three-guitar band, his work has always amazed me."

Powell's performance was captured with a Neumann U87 on the low keys and an AKG 451 on the mid-range and high notes, all recorded to one track. Meanwhile, Van Zant's remark at the start of the song to "Turn it up" stemmed from his request to Al Kooper and Rodney Mills to increase the volume in his headphones.

Equipment manager Kevin Elson (left) and Rodney Mills at the Studio One board.Photo: GEMS/Redferns"Al had the good sense to leave that in there," says Mills. "Before a song started I'd usually hit 'record' pretty quickly, and in this case I captured Ronnie's comment as he approached the microphone and was getting ready to sing. In terms of the performance itself, like the rest of the band he pretty much knew the song. There may have been some imperfections as far as intonations and stuff like that, but Ronnie was very capable of going out there and singing the song one time through, from beginning to end, the way he felt it. And as Al had a great ear, we'd then go back and fix parts. The 'Sweet Home Alabama' vocal was pretty much all done on one track in just a few takes, and then Ronnie doubled himself pretty quick, too. He didn't do much outside of what he was very comfortable with, so the doubling was not a hard thing for him to do. In fact, Al really liked to double things. Hence all the doubled guitars and layering on tracks like 'Freebird'.

Equipment manager Kevin Elson (left) and Rodney Mills at the Studio One board.Photo: GEMS/Redferns"Al had the good sense to leave that in there," says Mills. "Before a song started I'd usually hit 'record' pretty quickly, and in this case I captured Ronnie's comment as he approached the microphone and was getting ready to sing. In terms of the performance itself, like the rest of the band he pretty much knew the song. There may have been some imperfections as far as intonations and stuff like that, but Ronnie was very capable of going out there and singing the song one time through, from beginning to end, the way he felt it. And as Al had a great ear, we'd then go back and fix parts. The 'Sweet Home Alabama' vocal was pretty much all done on one track in just a few takes, and then Ronnie doubled himself pretty quick, too. He didn't do much outside of what he was very comfortable with, so the doubling was not a hard thing for him to do. In fact, Al really liked to double things. Hence all the doubled guitars and layering on tracks like 'Freebird'.

"Ronnie had a passion for learning something, and once he learned it he didn't vary from that. In fact, when he was writing a song, he would tend to avoid jamming along with the rest of the band on vocals, trying to formulate the number. His method of working was to actually sit in a corner and get the idea instilled in his head before he would do anything. Sometimes he would write the lyrics on the spot as the band was jamming the song, and he'd also come up with the melody in his head and kind of rehearse to himself. He was sensitive about doing stuff and not appearing to have it together. He may not have always sung with perfect pitch, but he liked to have things together, especially as far as the lyric, the melody and the attitude with which he approached the song. Ronnie had an exceptional gift for telling a story and making you believe it."

Nevertheless, there was still room for improvisation, such as Van Zant's "My, Montgomery has the answer," during Powell's piano solo at the end of the song.

"Al certainly helped in coming up with some ad libs that Ronnie did throughout the song," says Mills. "And then there was Al himself, going out into the studio and doing his best impression of Neil Young."

This refers to Kooper softly singing 'Southern Man' during the second verse, following Van Zant's line, "Well, I heard Mister Young sing about her."

"Al did that intentionally," Mills recalls. "It was a moment of inspiration after Ronnie did his vocal, and I don't think Al had any preconception of that at all until the moment he said, 'Let me go out there and do something real quick.' Afterwards, I think there was some discussion whether to use it or not, and although it did end up on the finished record I know some people still aren't aware it's there."

Sometimes there, sometimes not; Ed King's count-in to the song doesn't appear on all versions of 'Sweet Home Alabama', yet Rodney Mills thinks the ones that do have acquired it from the original tape.

"Back in those days, when you were mixing you did not mute out anything," he says. "You just edited things out, so someone must have found the original mix tape and reinserted that count-in. Still, it sounds to me like whoever did that processed it to get it up to a volume that everybody can hear. I probably had a room mic out there, and Ed must have been standing close to it when he did the count-in."

Now Muscle Shoals Has Got The Swampers...

Including backing vocals by Al Kooper, Ed King and Leon Wilkeson, one day was all that was needed to record 'Sweet Home Alabama', bar the Sweet Inspirations' own backing vocals being added in California — the first female voices to appear on a Lynyrd Skynyrd song — prior to the mix.

The floor plan for the 'Sweet Home Alabama' session.Photo: GEMS/Redferns"It wasn't one of those all-night sessions," says Mills, "even though most of the sessions back then tended to be that way, whether they needed to be or not. People would just hang out and listen to something over and over again, but in this case the recording didn't take long because, at that point, the band members weren't trying to use the studio as a creative tool. They were trying to get down what they played live on the song, while for his part Al Kooper had a good sense of the band and obviously a lot more studio experience than they did.

The floor plan for the 'Sweet Home Alabama' session.Photo: GEMS/Redferns"It wasn't one of those all-night sessions," says Mills, "even though most of the sessions back then tended to be that way, whether they needed to be or not. People would just hang out and listen to something over and over again, but in this case the recording didn't take long because, at that point, the band members weren't trying to use the studio as a creative tool. They were trying to get down what they played live on the song, while for his part Al Kooper had a good sense of the band and obviously a lot more studio experience than they did.

"They had a great idea of how they wanted to sound live, and Al had a better sense of what it took to make a good record, which is why there was all the layering and the ad-libs that they wouldn't necessarily reproduce in concert. I recorded quite a lot of stuff with Al back in those days, because Studio One was the centre of recording for all the projects he was doing, and he sometimes had ideas that the band didn't agree with. In fact, when the guys weren't there, he'd occasionally go in and play a guitar part or a keyboard part, and then when they came in they sometimes took it personally, did not like what he'd done, and were very vocal about this. I remember one time, Billy Powell was really upset that Al had actually played a B3 part on one of the songs. As it happens, Al was a great B3 player, but to them it was a no-no for anybody else to play on their record.

"I mean, they did invite a couple of people to come in and play, but usually it would be to do something that they themselves didn't play. Don't forget, this was a three-guitar band, and on guitar all those guys could play Al Kooper under the table. So, if they came in and Al had put a guitar part on there, it was like 'How dare you?' Al had his own ideas about things, and he was not a passive record producer, but he was working with a band that pretty much had their own ideas about things, too. Outside the studio, Al and the band members were great friends. Inside the studio, they were sometimes almost at war with each other. But that's not to say they didn't make good records together, and I give Al great credit for what he did with them."

Afterwards

'Sweet Home Alabama' was performed by the latest incarnation of Lynyrd Skynyrd, featuring Johnny Van Zant in place of his late brother, when the band was recently inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, of which their former engineer is also a member.

"I thought them performing that song in Georgia was great," comments Mills, who, after becoming an independent producer in 1986 and working on projects with, among others, 38 Special, Gregg Allman and the Doobie Brothers, went on to form the Atlanta-based Rodney Mills' Masterhouse in 1994, where he has since mastered records by the likes of Pearl Jam, Rage Against the Machine, the Wallflowers, the Atlanta Rhythm Section, Bonecrusher and many, many more.

"The thing that strikes me about Skynyrd more than anything else is that there were only four years between them recording their first album and Ronnie's death in 1977," he says. "The songs that those guys came up with during that time were amazing, as was everything that happened, and it was pretty neat to have been involved with some of that, as well as to have been there during the heyday of Southern rock music."