Max Farrar: we take on a well–crafted contemporary pop tune with a massive number of tracks, and create two different mixes.

This month, we’re treating you to two mixes: my colleague Sam Inglis and I had need of an interesting project on which to test some gear, and Max Farrar’s high-track–count pop track ‘Valley Girls’, with its decent recording quality, neat arrangement and catchy melodic hooks, fitted the bill nicely. Our assessments of Max’s recordings weren’t miles apart, but we steered our mixes in different directions — you can hear Max’s original, Sam’s and my mix on the SOS web site (http://sosm.ag/jan15media). I’ve written up my approach, and Sam’s added some valuable insights in his ‘Alternative Mix’ box.

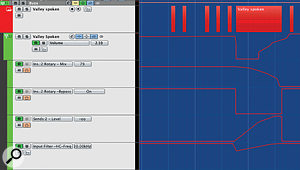

We often preach about ‘getting things right at source’, whether that relates to arrangements and instrumentation, capturing sounds with mics, customising synth presets, or whatever. Max had mostly done a stirling job: the song worked well; hard work had clearly been invested in the arrangement, and most recordings (the vocals in particular) sounded great. There were a couple of issues, though. The bass part’s long-attack ‘side–chained’ feel meant it often fought the groove instead of driving it. While not overly problematic, there were some guitar–tuning issues in places. I was less concerned about the daunting number of tracks, as everything seemed to have a place, and mostly it was due to the extensive double–tracking and layering of backing vocal (BV) parts. Finally, while Max’s mix sounded decent in places, it failed to deliver its payload: the choruses and outro just didn’t make me sit up like they should. Despite the huge number of tracks, the arrangement has been well thought out and neatly structured. Roughly the top third of this screen is taken up by the vocals alone!

Despite the huge number of tracks, the arrangement has been well thought out and neatly structured. Roughly the top third of this screen is taken up by the vocals alone!

Prep School

Much of the effort in crafting a good mix isn’t in the mixing, it’s more about removing obstacles to make the mix process hassle–free. Basic project housekeeping is time well spent, and it’s best if you can resist the temptation to start mixing at this stage. I went through, organising, renaming and grouping the sources, placing things in Folder tracks and so on, to make navigation easy. I also auditioned each source, listening for noise issues (there were very few) and to see if any editing might be required.

Most of the work at this stage revolved around the vocals, which were obviously the star turn. They’d been sung well and captured with a Neumann U47 tube mic, but there were still breath noises, lip smacks and a few timing issues, with consonants from BV layers not being quite as ‘together’ as I’d like. When the timing of such things on layered vocals isn’t bang on, it can drag your ear’s focus around the stereo field, which is unpleasant — so I went through the BVs, splitting out and aligning or muting breath sounds and critical consonants to make things tighter, using the drums as a reference. You can often remove the esses from most layers completely, leaving just a couple (on centre– or opposition–panned parts). I also used Cubase’s built-in Variaudio to iron out a few minor pitch issues, but was careful not to overdo it; some of the magic thickening in layered vocals is due to the subtle pitch variations. I’d lavish more attention on the lead vocals later, but for now I just did a little de–essing.

I also set up LCR pan positions for all tracks, and established a rough mix level, based on the loudest section of the song (the last chorus/outro). I almost always start with the LCR pan system, whereby tracks are set to 100 percent left or right, or dead centre. I might later narrow some buses in the mix, or move things into the ‘gaps’ for effect, but the LCR approach sets up a nice, wide sound stage, leaving plenty of space for critical elements in the centre.

All About That Bass

The bass sound was really the only major problem with the recordings. The final sound was achieved by radically EQ’ing the original part and hitting it hard with an analogue–style compressor and limiter, before blending the result with a triggered synth patch and running the mix through a chorus plug–in.I started by training my sights on that bothersome bass part, which I felt would make or break my ability to craft a good mix. My instinct was to eradicate that long drawn–out attack envelope using compression and distortion, hoping that this would also make the sound more audible on small speakers and that I could use a transient shaper to dial in some definition. It didn’t work brilliantly! My next attempt used Variaudio to extract MIDI notes to play a Cubase Prologue synth patch. I struggled with this too: detecting the right note–onset times proved tricky, and I’d neglected to set a suitable project tempo before editing. Grrr. I might have been better off tracking a new part or asking Max to bounce the part with a different sound but, instead, I opted for radical equalisation to emphasise the part of the sound I wanted, and set the compressor and brickwall limiter in VladG’s Limiter No. 6 to hammer things into shape. I then finessed the timing of the MIDI notes and filtered the Prologue part, blended the two sounds together, and ran the result through Cubase’s Chorus to add a little width. Phew!

The bass sound was really the only major problem with the recordings. The final sound was achieved by radically EQ’ing the original part and hitting it hard with an analogue–style compressor and limiter, before blending the result with a triggered synth patch and running the mix through a chorus plug–in.I started by training my sights on that bothersome bass part, which I felt would make or break my ability to craft a good mix. My instinct was to eradicate that long drawn–out attack envelope using compression and distortion, hoping that this would also make the sound more audible on small speakers and that I could use a transient shaper to dial in some definition. It didn’t work brilliantly! My next attempt used Variaudio to extract MIDI notes to play a Cubase Prologue synth patch. I struggled with this too: detecting the right note–onset times proved tricky, and I’d neglected to set a suitable project tempo before editing. Grrr. I might have been better off tracking a new part or asking Max to bounce the part with a different sound but, instead, I opted for radical equalisation to emphasise the part of the sound I wanted, and set the compressor and brickwall limiter in VladG’s Limiter No. 6 to hammer things into shape. I then finessed the timing of the MIDI notes and filtered the Prologue part, blended the two sounds together, and ran the result through Cubase’s Chorus to add a little width. Phew!

Kick Start

The drums and percussion occupied a hefty 22 tracks, with several kick and snare samples, forward and reverse cymbals, hand claps, shakers and some loops. As the sounds worked pretty well, I had only a few aims: first, to make sure the kick and snare remained strong and audible, combining with the bass to create a firm rhythmic foundation; and then to EQ and balance the percussion parts so they didn’t jar or mask each other. I’d EQ the guitars, keys and synths around the rhythm parts, so I soloed the drums, percussion, bass and vocals and set to work.

The main kick was treated to a hefty 7.5dB boost at 100Hz, another (6dB) at 500Hz, and a deep notch at 200Hz. In lay terms this emphasised the kick’s ‘knock’ while minimising low–mid mud (the 150–250Hz area can be a real battleground!). Cubase’s Compressor, with a 20.5ms attack, 208 release, and about 6.5:1 ratio, was then set to yield about 5dB of gain reduction (I wasn’t aiming for 5dB, that’s just what sounded right!).

For the kick that plays during the intro, I did a similar thing — a low–end boost, a dip at 200Hz (there’s something about that region I don’t like on kicks) and a boost higher up, this time at 3.45kHz. The compressor, at 8:1, was almost limiting, but just tickling the gain–reduction meter. An instance of Cubase’s EnvelopeShaper was used to put more emphasis on the attack.

Snare Crunch

On pop drums, the snare needn’t sound too natural. After experimenting with various distortion plug–ins, a bit crusher was used, mixed in at about 30 percent wet to add a little edge and definition.Most snare hits doubled a kick, so I rolled the bottom off the main snare at about 90Hz. I also rolled off the top end from 6.5kHz, to make room for the cymbals and whooshing noises that created a nice suck–and–blow effect. Sensing that the snare could sound ‘tighter’, I removed some of its tail with Cubase’s Expander, with a very short attack, a ratio of 3.5:1 and a medium release. I also experimented with distortion treatments for the snare, settling on Cubase’s Bit Crusher, on its 8–bit setting with its Mix slider at 32 percent wet. This kept plenty of the ‘real’ snare sound while also delivering a nice, crunchy ‘attitude’. As the mix progressed, I added a touch of EQ (2dB boost around 500Hz to 2kHz) and a hint of reverb, courtesy of Cubase’s REVerence plug–in, which I’d set up as a send effect.

On pop drums, the snare needn’t sound too natural. After experimenting with various distortion plug–ins, a bit crusher was used, mixed in at about 30 percent wet to add a little edge and definition.Most snare hits doubled a kick, so I rolled the bottom off the main snare at about 90Hz. I also rolled off the top end from 6.5kHz, to make room for the cymbals and whooshing noises that created a nice suck–and–blow effect. Sensing that the snare could sound ‘tighter’, I removed some of its tail with Cubase’s Expander, with a very short attack, a ratio of 3.5:1 and a medium release. I also experimented with distortion treatments for the snare, settling on Cubase’s Bit Crusher, on its 8–bit setting with its Mix slider at 32 percent wet. This kept plenty of the ‘real’ snare sound while also delivering a nice, crunchy ‘attitude’. As the mix progressed, I added a touch of EQ (2dB boost around 500Hz to 2kHz) and a hint of reverb, courtesy of Cubase’s REVerence plug–in, which I’d set up as a send effect.

With the kick, snare and bass working well together, the basic rhythm was coming together nicely. The claps, cymbals and shakers didn’t sound bad, but I applied high–pass filters as high as I dared; you needn’t do this for every mix, but in a dense pop arrangement it really helps to clear space. The claps were also treated to their own ambience reverb patch courtesy of REVerence, partly to push them back, and partly to thicken the sound. Reverbs are usually used as send effects, but as this was intended to alter the sound’s character I used it as an insert — I could later send the result to any effects I felt were required.

The kick, snare, shakers, claps and cymbals left little sonic space for the loops, so I did little more than bracket them with high– and low–pass filters and notch out a few frequencies, so they’d contribute their feel without clashing with anything. To make it fit with the other sounds, the breakbeat loop was also treated to a healthy HF–shelf boost (9.5dB from 2kHz), the brightening effect’s excesses being tamed by a 7kHz LPF. There’s no magic in these numbers — it just sounded right.

All of the drums and percussion were routed to a subgroup, at which point they were treated to a little dynamic range reduction to gel things together — including some analogue–style clipping, which seemed to leave the impact of the transients more intact than limiting. The smile EQ was added later, as the mix evolved.I routed the drum/percussion parts to a subgroup, where I used VladG’s excellent freebie Limiter No.6 plug–in. The dual aim was to ‘glue’ the rhythm section together and make it a little more snappy and aggressive. The main jobs were done by the plug–in’s compressor, which applied about 7dB of gain reduction in the loudest section, and the soft clipper, which shaved a fraction off the peaks in a slightly ‘harder’ way than you can do with a limiter — it doesn’t ‘soften’ drum transients so much. It’s easy to overdo this sort of thing, and I found myself backing off the effect a few times as the mix evolved. Later, I’d add the gentlest hint of a ‘smile’ curve on this bus with Cubase’s channel EQ.

All of the drums and percussion were routed to a subgroup, at which point they were treated to a little dynamic range reduction to gel things together — including some analogue–style clipping, which seemed to leave the impact of the transients more intact than limiting. The smile EQ was added later, as the mix evolved.I routed the drum/percussion parts to a subgroup, where I used VladG’s excellent freebie Limiter No.6 plug–in. The dual aim was to ‘glue’ the rhythm section together and make it a little more snappy and aggressive. The main jobs were done by the plug–in’s compressor, which applied about 7dB of gain reduction in the loudest section, and the soft clipper, which shaved a fraction off the peaks in a slightly ‘harder’ way than you can do with a limiter — it doesn’t ‘soften’ drum transients so much. It’s easy to overdo this sort of thing, and I found myself backing off the effect a few times as the mix evolved. Later, I’d add the gentlest hint of a ‘smile’ curve on this bus with Cubase’s channel EQ.

Under The Bridge

The bridge needed to build to emphasise the ‘bigness’ of the ensuing chorus. To achieve that, a few effects were used on the vocals, but a lot of automation was used, here on the spoken vocal parts but also on the kick drum.There was one more kick part during the bridge. Max had created some lovely synth and vocal parts for this section and I wanted to strip things back, both to show these off, and to build the anticipation so that the ensuing chorus/outro section would demand attention. To this end, I applied some effects on the backing vocals. A rotary speaker, for example, was automated to come in on the spoken vocals, and I made extensive use of level, low–pass filter and frequency automation. What you can hear going on with the kick in that part is a combination of subtle EQ and an automated Cubase EnvelopeShaper plug–in, with the attack phase increasing from 2dB to a whopping 18.2dB near the end of the section (making the drum bus processor work hard). As the bridge ended, I cut everything out except for a reverb tail — and as that tail ‘lands’, the chorus comes crashing back in.

The bridge needed to build to emphasise the ‘bigness’ of the ensuing chorus. To achieve that, a few effects were used on the vocals, but a lot of automation was used, here on the spoken vocal parts but also on the kick drum.There was one more kick part during the bridge. Max had created some lovely synth and vocal parts for this section and I wanted to strip things back, both to show these off, and to build the anticipation so that the ensuing chorus/outro section would demand attention. To this end, I applied some effects on the backing vocals. A rotary speaker, for example, was automated to come in on the spoken vocals, and I made extensive use of level, low–pass filter and frequency automation. What you can hear going on with the kick in that part is a combination of subtle EQ and an automated Cubase EnvelopeShaper plug–in, with the attack phase increasing from 2dB to a whopping 18.2dB near the end of the section (making the drum bus processor work hard). As the bridge ended, I cut everything out except for a reverb tail — and as that tail ‘lands’, the chorus comes crashing back in.

Guitars

The two acoustic rhythm guitar parts, each double–tracked, just needed to drive the rhythm along and add to the sense of width. I opposition–panned the doubles to the extremes, left the higher–pitched ‘emphasis’ part unprocessed, but aggressively high–pass-filtered the lower part, leaving little by way of pitch information there. On its own it sounded awful, but against the rest of the track it worked just fine.

Although some electric guitar parts suffered from slight tuning issues, I didn’t bother with pitch processing, as by the time I’d rolled off the bottom end these issues became pretty much inaudible in context. Again, there were two main parts, both double–tracked, and again I opposition–panned them, the lower part being high–pass filtered at around 120Hz, and the higher one up at 300Hz. Once I’d balanced the two to my satisfaction and added a very short stereo delay patch for one part on a send, I routed both electric guitars to a dedicated subgroup, on which I’d placed an instance of Tokyo Dawn/Variety Of Sound’s Slick EQ. This plug–in, another freebie, includes a switchable loudness–compensation system: when engaged, you can make EQ boosts or cuts without the perceived level changing. This made it easy to make small tweaks to the overall electric guitar sound as the mix progressed, without me having to go back to the individual tracks. I ending up adding a bit of mid boost and some HF–shelf attenuation, level automation and I automated the send to one of the two reverbs.

Vocals

While the lead vocal part in much of the song worked with the backing vocals, I wanted a different, softer sound for the part in the intro, and this was achieved with the excellent freebie plug–ins Tokyo Dawn/Variety Of Sound Slick EQ and VladGs Molot compressor, along with automated use of the global reverb and delay effects. (The Cubase compressor you can see here was only used to add gain when refining the mix; it’s not actually compressing.)Having edited the BVs and bussed the doubles to their own subgroups, I didn’t have a huge amount to do to get them working reasonably well. Most parts were treated to little more than a tiny bit of EQ (no more than about 3–4dB of boost or cut at any one frequency), compression and reverb before I set to work on the level automation. The ‘Oooh’ sounds were treated to the firmest compression, with about 8dB of gain reduction on that group bus, but others only needed around 3–4dB at most. The trickiest bit was finding the right level for the ad libs, but that was just a case of being happy with my judgment — there was no great technical challenge there.

While the lead vocal part in much of the song worked with the backing vocals, I wanted a different, softer sound for the part in the intro, and this was achieved with the excellent freebie plug–ins Tokyo Dawn/Variety Of Sound Slick EQ and VladGs Molot compressor, along with automated use of the global reverb and delay effects. (The Cubase compressor you can see here was only used to add gain when refining the mix; it’s not actually compressing.)Having edited the BVs and bussed the doubles to their own subgroups, I didn’t have a huge amount to do to get them working reasonably well. Most parts were treated to little more than a tiny bit of EQ (no more than about 3–4dB of boost or cut at any one frequency), compression and reverb before I set to work on the level automation. The ‘Oooh’ sounds were treated to the firmest compression, with about 8dB of gain reduction on that group bus, but others only needed around 3–4dB at most. The trickiest bit was finding the right level for the ad libs, but that was just a case of being happy with my judgment — there was no great technical challenge there.

That said, while the BVs were working acceptably, I wasn’t entirely satisfied, and after discussing a draft mix with Sam, he suggested using multi–band compression on the BV bus. I tried and ironed out the few remaining annoyances pretty efficiently. I’ll be using that trick again!

The lead vocals had been tracked as several different parts, but there was an easy logic to Max’s organisation. A single–tracked part took care of the opening verse, and this one I treated to a slight mid–range emphasis with another instance of Slick EQ, along with some 5–6dB warm–sounding compression, courtesy of another VladG freebie, Molot. Later, having already automated the level fader on this part, I realised it was a little low in the mix, and added a gain plug–in.

This part was sent to both of my reverb sends. The delays I’d set up for the guitar were also used, with the send level being automated to provide a few spot delay effects, without the delay signal compromising the vocal intelligibility.

For much of the rest of the song, the lead vocal was so closely tied in with the BVs that I ended up routing these parts to the BV bus. This comprised a double–tracked part, which I panned hard left and right, which left the impression of a thicker–sounding part in the centre — I tried panning both to the centre, but this just seemed to sound better. Each of the two parts’ dynamic range was controlled by an instance of Cubase’s Vintage Compressor (an 1176 FET compressor emulation), with quite a slow attack and medium release — but as one take had been sung a little more dynamically than the other, the maximum amount of gain reduction I applied to each was very different — that’s something no preset can get right!

Synths & Effects

The synth and various whooshing effects were all in good order, so I referenced Max’s mix to see what he’d had in mind, and decided to stay true to the spirit of what he’d done while also indulging my creative urges. The opening ‘blip synth’ part, for instance, I ran through a bass patch in Cubase’s Amp Simulator plug–in, to make the tone a little more ‘warm’ and ‘rounded’. I used pan automation to make the intro move across the stereo stage, and an instance of Cubase’s Stereo Enhancer to add a little more overall width, before adding an instance of Cubase’s EnvelopeShaper and automating the release time (for the intro only) just for interest. Other than sending a tiny bit of it to the REVelation effect, that was pretty much it, other than to use level automation to mute the part in one spot where I felt it was superfluous.

Route Manoeuvre

The vocals were sent to a separate bus to the rest of the mix, which was treated to dynamics processing and EQ — courtesy of yet more instances of Tokyo Dawn and VladG plug–ins — to make it work better with the vocals. This and the vocal bus were then routed to the main stereo bus, which featured no processing (although a limiter was used to add a bit of level at the end). This way, the vocals seemed to suffer less from the bus processing that the style of track seemed to be crying out for. I experimented with some unusual bus routing in this mix. Working back from the master stereo bus, this was fed by three separate buses — one for the backing vocals and the chorus lead vocals, with the multi-band compressor patched in, another one for all the instrument parts, and that subgroup for the earlier lead vocal too. That enabled me to compress the ‘backing track’ independently of the vocals. Why? Well, the track really seemed to benefit from the bus compression that I had set up, courtesy of Tokyo Dawn Labs’ TDR Feedback Compressor II, and from a touch of stereo-width enhancement, but the vocals seemed to suffer from this setup. Leaving that all set up but routing the vocals around the compressor, before everything hit the main stereo bus, proved an effective solution .

The vocals were sent to a separate bus to the rest of the mix, which was treated to dynamics processing and EQ — courtesy of yet more instances of Tokyo Dawn and VladG plug–ins — to make it work better with the vocals. This and the vocal bus were then routed to the main stereo bus, which featured no processing (although a limiter was used to add a bit of level at the end). This way, the vocals seemed to suffer less from the bus processing that the style of track seemed to be crying out for. I experimented with some unusual bus routing in this mix. Working back from the master stereo bus, this was fed by three separate buses — one for the backing vocals and the chorus lead vocals, with the multi-band compressor patched in, another one for all the instrument parts, and that subgroup for the earlier lead vocal too. That enabled me to compress the ‘backing track’ independently of the vocals. Why? Well, the track really seemed to benefit from the bus compression that I had set up, courtesy of Tokyo Dawn Labs’ TDR Feedback Compressor II, and from a touch of stereo-width enhancement, but the vocals seemed to suffer from this setup. Leaving that all set up but routing the vocals around the compressor, before everything hit the main stereo bus, proved an effective solution .

I used only three basic send effects on this mix: two reverbs and a delay (actually, two hard–panned mono delays). The REVelation send that I’ve alluded to already was mostly an ambience patch with only 12 percent ‘tail’, while the REVerence convolution reverb was set to the LA Studio preset, which I use a lot. To prevent things getting too splashy, I preceded it with an instance of Cubase De–esser. That approach allows you to keep the reverb sound fairly bright, without paying too high a price!

It took several iterations of this mix, comparing the results with references and incorporating feedback from Sam and Max, before I was really happy and I could call it job done. Phew!

Remix Reactions

Max Farrar: “Awesome mixes! They each have their own flavour. In Matt’s mix, I really like the rebalance of the harmonies — very crisp and clean — and I love that it’s more audible than my own balancing. I dig the clarity of the mix overall. I know the bass was kind of a bitch to deal with — I realise now it was the wrong bass sound — it was too subby, with not enough meat to it. It has to do with the room modes in my studio; I have a peak then a huge null in my sub, so that bass happened to sound powerful and mask the fact that I didn’t have enough harmonic content in that sound, I think.

“I love what Sam did too. The muffled thing was bothering me for sure, and I feel like he really cleared up a lot of the spectrum! It’s somewhat of a departure from the original sound of the track, and I think it goes to show that I don’t need to use so much reverb/delay in my mixes, making them wash out a bit. I suppose it depends on the vibe, but either way, I loved hearing this. It’s helped me get a lot of perspective on mix choices. Thank you both. Much appreciated!”

Alternative Mix

Fabfilter’s Pro–MB, set up to act as a dynamic EQ to brighten the lead vocals.When first I heard Max Farrar’s mix of his track ‘Valley Girls’, I was shocked that he felt it was in need of rescuing! It was a polished production, and obviously very well recorded. Max’s balance made good sense, there were no jarring holes or peaks in the frequency spectrum, and there was lots of nice ear candy to keep the listener interested.

Fabfilter’s Pro–MB, set up to act as a dynamic EQ to brighten the lead vocals.When first I heard Max Farrar’s mix of his track ‘Valley Girls’, I was shocked that he felt it was in need of rescuing! It was a polished production, and obviously very well recorded. Max’s balance made good sense, there were no jarring holes or peaks in the frequency spectrum, and there was lots of nice ear candy to keep the listener interested.

After a few listens, though, I began to understand what Max meant by its having a “muffled quality”. There was a slight softness and sogginess to the mix, which wasn’t helped by a prominent long reverb and a busy arrangement; and the bass sound, with its slow attack, felt as though it was dragging the tempo of the track downwards. I also decided that a low vocal level in Max’s mix was underselling a fantastic performance and recording.

In terms of ‘rescuing’ the mix, then, there were three main aspects to consider. The first was the bass sound. Having failed to re–shape its flabby dynamic envelope with compression, I dropped the audio file into Melodyne and used its analysis to generate a MIDI part. Somewhat to my surprise, this worked perfectly first time. The part itself was good, so I used this MIDI track to trigger a different bass sound from Fabfilter’s Twin 2 soft synth. This gave me the attack and low–end thump that was missing from the original, but on its own it sounded rather small, so I blended it back in with a heavily processed version of the original. I used automation through the song to rebalance the two parts in places, and the combination made for a big sound with a much more solid and urgent feel.

The second challenge was to ‘de–muffle’ and open up the mix. This was a matter of many small steps rather than one giant leap, beginning with some pruning of the arrangement: I didn’t feel that the ‘blip’ synth melody at the start needed to be repeated throughout the song, for example. I then wielded aggressive high–pass filtering on sources such as the acoustic guitar, aiming to clear out the low mid–range.

Effects–wise, I set up four reverbs and two delays, but rationed their use. Two reverbs were purely for vocals, another just for the snare; and the only reverb that I used across multiple sources was a very short ambience patch from Acon Digital’s Verberate. This gave the electronic sources a sense of space and air, without losing any of their impact. Compression can be the enemy of an open mix, and is rarely necessary on electronic instruments in any case, so I used it very sparingly. Where I felt things could do with thickening up, I turned instead to saturation plug–ins, such as Fabfilter’s Saturn and SoundToys’ Radiator.

That left the third challenge: restoring the vocals to their rightful place of honour. Apart from applying filtering and other effects to recreate Max’s breakdown section, I did very little with the backing vocals, beyond bussing them to groups and thickening them with reverb and more MicroShift. Most of my attention was focused on the lead vocal, which wasn’t quite commanding the mix as I’d have liked. I began by chucking out most of the vocal doubles, as the main lead vocal performance was plenty good enough to stand on its own. It was also very nicely recorded, but I wanted to make it cut through without it sounding harsh or spitty, and found it hard to do so consistently using conventional EQ and compression. I eventually hit on the idea of using Fabfilter’s Pro–MB as a dynamic equaliser, which made it possible to brighten the vocal without exaggerating sibilance, and push the mid–range without introducing honkiness. Actual level control I left almost entirely to automation, and having kept the rest of the mix very dry, I felt there was room for a fairly expansive combination of reverb and delay on the lead vocal. Sam Inglis