Get the most from your computer's CPU by learning how to put your effects plug-ins where they really count. Plus, find out how to increase your mixing power by incorporating hardware effects units into your software mixdown.

Those of us who started recording back in the days when hardware was used for everything soon got the hang of where signal processors could or could not be connected. However, the software world isn't always quite so intuitive, especially if you've never used a hardware mixer before. In the virtual world, effects boxes are often replaced by plug-ins, and the first thing you need to know when patching in a plug-in is whether it is an 'effect' or a 'processor'. This basic designation is something that we've explained many times in the past in relation to hardware, but it also applies to plug-ins. When it comes to new users, it's one of the first places they come unstuck, so I make no apologies for recapping.

Combining Plug-ins

My rules for using effects and processors have to be adapted slightly when you want to combine an effect and a processor. For example, you may want to place an EQ, which is a processor, before a reverb plug-in, which is an effect. In most cases, where effects and processors are combined in this way, the resulting combination can be considered as still being an 'effect', so placing compressors and equalisers before or after an effect being used in an auxiliary send is quite OK. As a rule of thumb, go by the status of the last plug-in in the chain.

Effect Or Processor?

Although pretty much any plug-in that changes the sound in some way can be thought of as being a signal processor of some kind, the 'effect' and 'processor' designation helps us divide these devices into their two main categories, which in turn tells us where we can connect them. Put simply, a processor passes the whole signal and imparts some change to it, the most common examples being EQ, compression, limiting, gating, expansion, distortion, and filtering. Effects, on the other hand, are designed to be combined with the untreated signal, which is why most feature a wet/dry mix control. Prime examples of effects are delay, echo, reverb, chorus, and flanging — in fact pretty much anything that uses delay as part of its means of operation.

Figure 1. Using multiple insert effects on one channel.Each channel on a hardware mixer (at least, any half-decent one) includes something called an insert point, a physical connection that allows you to interrupt the signal path and send the signal through some external effect or processor. Virtual mixers also have insert points, but instead of these feeding external hardware boxes they allow you to place a plug-in into the signal path. Insert points are very flexible, so you can use either effects or processors in them — the only thing you have to remember is that when using effects the amount of effect added is adjusted using the mix control on the effect plug-in itself. Most virtual mixers allow you to add multiple insert plug-ins, in which case the signal passes through them sequentially, usually from the top of the screen to the bottom, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Using multiple insert effects on one channel.Each channel on a hardware mixer (at least, any half-decent one) includes something called an insert point, a physical connection that allows you to interrupt the signal path and send the signal through some external effect or processor. Virtual mixers also have insert points, but instead of these feeding external hardware boxes they allow you to place a plug-in into the signal path. Insert points are very flexible, so you can use either effects or processors in them — the only thing you have to remember is that when using effects the amount of effect added is adjusted using the mix control on the effect plug-in itself. Most virtual mixers allow you to add multiple insert plug-ins, in which case the signal passes through them sequentially, usually from the top of the screen to the bottom, as shown in Figure 1.

Setting Up An Effects Loop

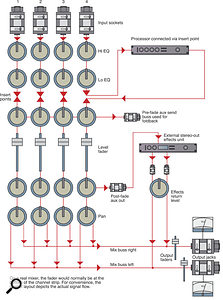

The other way to connect effects is to use a post-fade aux send, sometimes called an effects send. Each mixer channel will have one or more aux send controls, usually numbered. All the aux-one sends are mixed together and, on a hardware mixer, this mixed signal is sent via the master aux-one output socket to an external effects box. All the aux-two sends are mixed and feed the aux-two master control and output, which allows you to add a second effect. The output from an effects box fed from an aux send is then added back into the mix via a special input called an aux return, and these are often stereo simply because many effects boxes have stereo outputs. Although an aux return has a fancy name, it's still just another type of mixer input and it is added to the mix of all the other mixer channels feeding the stereo mix. Note that you don't have to return effects connected to aux send one to aux return one, though it sometimes helps keep your thoughts in order to do so. Figure 2 shows an effects send and return setup as it relates to a conventional mixer. The insert points are also shown, along with the pre-fade send normally used for foldback.

Figure 2. An effects send/return setup working with a conventional mixer.Virtual mixers employ a very similar system of aux sends, but, rather than feed an external effects box, the channel aux send controls are routed to an effect plug-in and the output from the plug-in is routed back into the stereo mix. Steinberg's Cubase does this by using a virtual effects rack, which is conceptually similar to the way things work with a hardware mixer, though Emagic Logic does things slightly differently. With Logic, the channel post-fade aux sends can be routed to either physical soundcard outputs or to mixer busses, so the normal approach is to use a buss as an aux return and then route its output back into the stereo mix. The sends are then set up to feed this buss, and the desired effect slotted into the buss insert point. In terms of signal flow, this is again very close to what happens on a hardware mixer.

Figure 2. An effects send/return setup working with a conventional mixer.Virtual mixers employ a very similar system of aux sends, but, rather than feed an external effects box, the channel aux send controls are routed to an effect plug-in and the output from the plug-in is routed back into the stereo mix. Steinberg's Cubase does this by using a virtual effects rack, which is conceptually similar to the way things work with a hardware mixer, though Emagic Logic does things slightly differently. With Logic, the channel post-fade aux sends can be routed to either physical soundcard outputs or to mixer busses, so the normal approach is to use a buss as an aux return and then route its output back into the stereo mix. The sends are then set up to feed this buss, and the desired effect slotted into the buss insert point. In terms of signal flow, this is again very close to what happens on a hardware mixer.

If the effect is a reverb plug-in, turning up the aux-one send control on mixer channel one will send some of that signal to the reverb unit. When the output from the reverb is added back to the main mix, the audio signal on channel one will be heard with reverb added to it. Because the untreated part of the signal is still going via channel one, the plug-in's mix control should be set to 100 percent wet so that the only thing the plug-in contributes is effect, and not more of the original dry signal.

The great advantage of the aux send system is that a single reverb plug in (or other effect) can be used to treat as many mixer channels as you like. The character of the effects will of course be the same in all cases, but the amount of effect added can be adjusted independently for each channel using the channel's aux send control. Incidentally, post-fade sends are used for effects, so that when the channel fader is adjusted, the effects send level is automatically adjusted by the same amount, thus ensuring a consistent amount of added effect. If a pre-fade send were to be used, the effect level would remain constant even if the channel fader were turned right off.

While effects can be fed from the pre-fade aux send system, the same is not generally true of processors, as these are designed to work with no dry signal added. There are some exceptions, but for the most part these should be left to advanced users who know exactly what they are doing and why. If you learn nothing else from this article, it is important that you remember the rules for effect and processor connection: effects can be connected either via channel insert points or via the aux send system, but Processors should normally only be used in channel or subgroup insert points, not via an aux send loop.

Using Hardware Effects For Your Software Mixdown

One common problem is working out how to use an external hardware effect or processor with a virtual mixer. While most plug-ins are perfectly adequate for the task, hardware reverbs still tend to be better than many of their software counterparts, mainly because there's a limit to how much of a CPU's resources a plug-in can decently ask to tie up. The newer convolution reverbs are an exception, but they are very CPU hungry.

Figure 3. Setting up a send to a hardware reverb when using Emagic Logic with an external mixer.If you have an audio interface with more than two outputs, you can use an external hardware device, but exactly how you do this depends on whether you also have an external hardware mixer. I imagine most computer studio users will have at least a small hardware mixer to combine their soundcard outputs with the outputs from any external MIDI synths, in which case all you need is a pair of spare mixer inputs and you can use a hardware effects unit. The way this works is to set up the post-fade send in the virtual mixer as usual, but instead of routing it to an effects plug-in, you send it to one of the spare outputs on the audio interface. This output feeds the input to your reverb unit and the reverb unit's outputs go into the hardware mixer panned left and right, as shown in Figure 3 (right).

Figure 3. Setting up a send to a hardware reverb when using Emagic Logic with an external mixer.If you have an audio interface with more than two outputs, you can use an external hardware device, but exactly how you do this depends on whether you also have an external hardware mixer. I imagine most computer studio users will have at least a small hardware mixer to combine their soundcard outputs with the outputs from any external MIDI synths, in which case all you need is a pair of spare mixer inputs and you can use a hardware effects unit. The way this works is to set up the post-fade send in the virtual mixer as usual, but instead of routing it to an effects plug-in, you send it to one of the spare outputs on the audio interface. This output feeds the input to your reverb unit and the reverb unit's outputs go into the hardware mixer panned left and right, as shown in Figure 3 (right).

If you have spare audio interface inputs and your sequencer can add live inputs to the mix (as can the current versions of both Steinberg Cubase and Emagic Logic), you also have the option of feeding the hardware reverb outputs back into the mix directly, as shown in Figure 4 (below). This is useful if you don't use a hardware mixer. In some cases, working this way will add a little delay to the reverb because of the system latency, but as reverb is traditionally pre-delayed by several tens of milliseconds anyway, this is unlikely to cause problems.

It's less easy to use external processors as insert effects, especially if you have a limited number of additional audio outputs on your interface card, but it can be done. The usual method is to route the track to be processed to one of the spare audio outputs, then feed it into a hardware mixer channel with the desired processor connected via its insert point. If there is no hardware mixer, then you can route the soundcard output directly to the processor before feeding the processor's output back into a spare soundcard input. If you run this setup, you may find that the system latency delays the processed input by too much, in which case you can either record the processed signal as a fresh audio track, or apply negative delay to the audio track being processed to bring the processed input back into line with the rest of the song. Of course you can only use as many hardware insert effects as you have spare audio interface inputs and outputs.

Delay Compensation

Figure 4. Using a hardware reverb with a virtual mixer.Every plug-in takes a finite time to process audio, so the output is delayed slightly relative to the input. This can be a problem when using sequencers that don't offer automatic plug-in delay compensation, as any processed tracks will play slightly late. Even where the host software does compensate automatically, it relies on the plug-in reporting its latency figure correctly — and not all do.

Figure 4. Using a hardware reverb with a virtual mixer.Every plug-in takes a finite time to process audio, so the output is delayed slightly relative to the input. This can be a problem when using sequencers that don't offer automatic plug-in delay compensation, as any processed tracks will play slightly late. Even where the host software does compensate automatically, it relies on the plug-in reporting its latency figure correctly — and not all do.

Furthermore, not all software handles plug-in delay compensation in the same way — in Emagic Logic, for example, you only get delay compensation in the channels, not in the busses or outputs. You may also have to check that plug-in delay compensation is active in the software's preferences. Where you're feeding a reverb from a send and adding only the wet signal back into the mix, this isn't usually a problem, because a few milliseconds of delay simply adds to whatever pre-delay value you've set anyway. However, with other effects it may become significant, so when you next contact your sequencer manufacturer to suggest new features, add full plug-in delay compensation to your list!