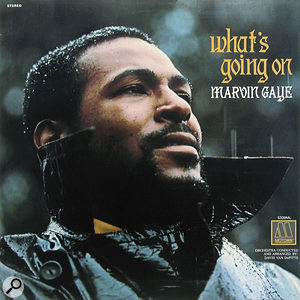

As the '60s came to a close, Marvin Gaye was forced to ask some serious questions about the world as he found it; the result was the sublimely soulful piece of social commentary, 'What's Going On'.

Photo: Getty/Michael Ochs Archives

Photo: Getty/Michael Ochs Archives

It has been hailed as Marvin Gaye's masterpiece and soul music's finest moment. What's Going On, a song cycle focusing on the shattered American dream of the early 1970s, melded a darkly atmospheric, jazzy sound with heartfelt lyrics about the country's military plight abroad and socio‑economic problems at home, to create what many still perceive as the apex of artistic musical expression. Released in May 1971, Gaye's 11th studio album cast the singer‑songwriter‑musician with the four‑octave vocal range — who had spent the past decade recording sensual R&B hits — in the role of a disillusioned Vietnam War veteran. The reason for his disillusionment? On his return, he discovers that the America whose values he's been defending is plagued by poverty, police brutality, drug abuse, abandoned children, urban decay and civil unrest. In more ways than one, What's Going On was different to anything that Gaye or Motown had previously issued, taking its inspiration from the classic track of the same name that he'd recorded in June 1970 and which, in March 1971, hit number two on the Billboard Hot 100.

A Change Of Direction

Hitsville USA, aka Motown Studio A, has been preserved as it was during its heyday, and is today open to the public as a museum. Photo: Motown Museum

Hitsville USA, aka Motown Studio A, has been preserved as it was during its heyday, and is today open to the public as a museum. Photo: Motown Museum

It was Renaldo 'Obie' Benson of the Four Tops who originally began penning the song after witnessing cops manhandle and arrest several young anti‑war protestors in San Francisco. Hence the lines "Picket lines and picket signs/Don't punish me with brutality”. Nevertheless, unwilling to meddle with the formula that had brought them success by way of relationship‑based songs, Benson's vocal‑group colleagues refused to sing about such an incendiary subject. And even when he offered it to protest singer Joan Baez after recruiting Motown in‑house composer Al Cleveland to help flesh out the lyrics, the still‑untitled number remained unrecorded. It was at this point that Marvin Gaye entered the picture.

For the previous few years, Gaye had felt increasingly frustrated by the lack of artistic freedom afforded him by the commercial, pop‑oriented edicts of the Motown hit machine and its autocratic founder Berry Gordy (who also happened to be his brother‑in‑law). Then, in March 1970, when a brain tumour claimed the life of Gaye's friend and collaborator Tammi Terrell, he plunged into a full‑blown depression. Refusing to sing on stage or in the studio, he made an unsuccessful attempt to join the Detroit Lions football team, before agreeing to record once more, but only on his own terms, which meant making artistic decisions without deferring to Motown's head honcho.

"In 1969 or 1970, I began to re‑evaluate my whole concept of what I wanted my music to say,” Gaye would later tell Rolling Stone magazine. "I was very much affected by letters my brother was sending me from Vietnam, as well as the social situation here at home. I realised that I had to put my own fantasies behind me if I wanted to write songs that would reach the souls of people. I wanted them to take a look at what was happening in the world.”

Accordingly, after a golf game with Obie Benson and Al Cleveland resulted in them playing Marvin Gaye the unfinished song back at his house, he came up with the title and added more lyrics, while also embellishing the melody on his piano. 'What's Going On', Gaye thought, would be ideal for the Originals, whose hits 'Baby I'm for Real' and 'The Bells' he had co‑written and produced. Benson convinced him otherwise, and so on June 10th, 1970, Marvin Gaye entered Studio A at Motown's Hitsville USA to record the song himself.

Ken Sands & The Funk Brothers

Marvin Gaye at work on a song, 1971.Photo: Redferns

Marvin Gaye at work on a song, 1971.Photo: Redferns

"One thing I'll say about Marvin is that he was always kind,” says Ken Sands, who was involved in the recording and the mix. "He was forceful in terms of what he wanted, a vision person in terms of what he was trying to do, but he was also a very sweet and gentle man who treated people calmly. That's who he was, and I loved him and I miss him.”

It was in late 1964, while still in high school, that Vincent Kenneth Shensky secured a job as a board operator at radio station WLIN FM in Lincoln Park, just southwest of downtown Detroit, running programmes and announcing ads and news bulletins. Thereafter, using the on‑air moniker of Kenneth Sands (now his legal name), he worked at several different stations in the Detroit area, until 1966, when he became a disc jockey at WTRX AM in Flint, Michigan. It was then that he met Clarence Ringo, the chief engineer at WCHB AM in Detroit, who was also working part‑time at a small recording studio called Magic City. Sands subsequently split his own work time between Magic City and local radio station WJLB, and used a demo reel of his sessions at the former to help land a staff job at Motown in 1967.

"I started out as an engineer doing basic rhythm tracks,” he recalls. "We would have three‑hour recording sessions and cut several tunes during each session with the Funk Brothers.”

Purported, according to the 2002 documentary film Standing In The Shadows Of Motown, to have "played on more number‑one hits than the Beatles, Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones and the Beach Boys combined,” the Funk Brothers were the in‑house musicians who provided the backing to most of the company's recordings from its inception in 1959 until its relocation to LA in 1972. Virtually anyone who played on the records could be classified as a Funk Brother, including Marvin Gaye, who acquitted himself pretty handily on the drums for acts such as the Miracles, the Marvelettes, Mary Wells, Martha & the Vandellas, the Supremes and Little Stevie Wonder. Nevertheless, only 13 people have been officially recognised (by NARAS, for a Lifetime Achievement Award, and on the Hollywood Walk Of Fame) as official members of the Funk Brothers.

Aside from some singles and albums by Earl Van Dyke, What's Going On was the first Motown record to actually credit the Funk Brothers' contributions. Before that, working alongside legendary in‑house songwriter‑producer Norman Whitfield, Ken Sands engineered Marvin Gaye's smash‑hit version of 'Too Busy Thinking About My Baby', his follow‑up to 'I Heard It Through The Grapevine', as well as the million‑selling 'That's the Way Love Is'.

Backing Tracks

"The rhythm tracks and overdubs for those songs were done at Studio A on West Grand Boulevard,” Sands explains. "Studio B, originally known as Golden World and located at 3246 West Davison, was mostly used for strings, horns, and lead and background vocals. The Funk Brothers would moonlight there before Berry bought the place, and after he did so it still had the original Neumann solid-state console and a Scully eight‑track machine.”

For its part, by the late‑'60s the Studio A control room housed an interesting, if rudimentary, curio. This comprised a frame within which there were two consoles: a six‑input mono desk in the centre and an eight‑channel stereo desk on the left side, with Langevin faders that could be assigned left, centre or right.

"It had echo sends but no EQ,” Ken Sands continues, "and although there was a 16‑channel wing with small rotary pots for 16‑track monitoring, that room contained just one Altec 604E monitor driven by a McIntosh 75 Watt amplifier. We couldn't mix in there; we could only record and overdub. Marvin and I did the stereo mix of 'What's Going On' in the Motown Center at the corner of Woodward Avenue and the Fisher Freeway, using the Electrodyne console that was on the 10th floor, along with a pair of Altec 604Es.”

Meanwhile, the Studio A live area, known as 'The Snake Pit', had chief engineer Mike McLean's home-built, five‑channel line amplifier, into which a musician could plug a guitar or bass. This went to a balanced patchbay and from there into the tape machine which, in 1968, was upgraded from an Ampex‑based, one‑inch eight‑track built by McLean to a two‑inch Ampex MM1000 16‑track.

"It was pretty much a standard system, with everything recorded direct for instrumental clarity and a 12‑inch speaker on the bottom of the DI that monitored what you plugged in,” Sands remarks. "All three guys — Eddie Willis, Robert White [guitar] and James Jamerson [bass — and how!] — played through that system and heard themselves coming out of that amplifier. We had to control the amount of ambient sound in the room, because about three feet from the amplifier was a Steinway grand on a short stick, and we didn't want guitar and bass leakage getting into the piano.

"Mike McLean was an extremely talented man. He'd listen to Deutsche Grammophon recordings and centre his engineering skills on what the Germans would do. His amp's five channels of guitar level ran from –30 at high impedance to +4 at 600 Ohms. It was very, very clean, with lots of negative feedback, and low‑distortion, high‑quality transformers on the inputs and outputs. There was a VU meter on each input, and a guitar's input would be adjusted at the loudest note to peak zero on the VU, providing maximum headroom. That line‑level output would be patched directly into the tape recorder — there was no mixing path — and this was how we worked with the guitars, bass and, later on, a Clavinet and the Fender Rhodes.

"Studio A had a wooden floor — it still does — and horizontal acoustic treatment of the walls, as well as a dropped ceiling. This gave it a very tight sound, and there were good sight lines between the musicians, who stood pretty close together. There were three isolation rooms that we used for overdubs, but when we were doing a basic session we could also use those rooms to isolate certain instruments — be they a harpsichord or a set of vibes — and ensure there was no leakage at all. The harpsichord room had a B3 [Hammond organ] with the Leslie [rotating speaker], which Lamont Dozier would usually play on the sessions he and the Holland brothers were producing.”

Not that Ken Sands recorded all of the instruments for What's Going On, or even for the title track. Indeed, during the label's halcyon years, it was standard Motown procedure for a rhythm track to be handled by several different staff engineers.

"Everything was done piecemeal,” Sands explains. "One engineer might record just the basic piano, bass and drums, maybe a guitar too, and then other engineers would overdub the rest of the instruments: conga, tambourine, bongos, another guitar, Wurlitzer piano, Rhodes piano, whatever, followed later on by the lead vocals and background vocals. Some of us would also do horn sessions or string sessions with the Detroit Symphony and [trumpet player] Johnny Trudell, which I enjoyed a lot. It wasn't about specialisation. Certain producers favoured certain engineers, but the work was distributed between everybody.”

Instrumentation

In the case of 'What's Going On', it was Steve Smith who recorded the basic drums, bass and piano.

"That's how Marvin would usually start his sessions,” Sands continues with regard to the general approach on Gaye's records. "He'd play the piano while Pistol [Richard 'Pistol' Allen] was on the drums and Jamerson was on bass, and he would also do a demo vocal along with that rhythm track on track one. The microphones that we used were tube Neumann U67s; they had an extremely clean sound, but they would also allow for a certain amount of distortion/compression that was just enough to give things an edge.

"Pistol would play a relatively small, dark mother-of-pearl Rogers drum kit that was actually designed for jazz. There was a large ride cymbal, a crash on the left, a small tom‑tom, a floor tom‑tom and snare. Pistol would keep that set tuned the way he liked it for playing — he was responsible for the drum sound after Benny Benjamin died.

"Benny was a heavy drummer with a broader sound,” Sands says. "Pistol, on the other hand, was a really good, close friend of mine, and he taught me how to play drums. Then there was Uriel Jones — they were consummate jazz musicians. To record Pistol, I would use just three mics: an RCA DX77 ribbon on the foot, a U67 on the snare, and a U67 overhead. People couldn't believe we were using a ribbon microphone on a bass drum — 'Why would you do that?' The wave front of a bass drum would tend to stretch the ribbon of a ribbon microphone, but that's what we used. That was the foot sound, that was Motown.”

As it happens, 'Pistol' Allen didn't drum on the sessions for the 'What's Going On' single or album. Looking for a different sound, Marvin Gaye assigned that role to Chet Forest, described by bass player Bob Babbitt as "more of a swing big‑band drummer, a very excellent musician and an unbelievable drummer,” in a 2010 Bass Guitar magazine article. It was Forest who played the song's main groove, while Gaye added an extra beat with a box drum.

Given that, according to Ken Sands, "the overall setup didn't really change” on Motown records, regardless of who the main artist was, when Steve Smith recorded the rhythm track for 'What's Going On', he likely saw Chet Forest drumming in the rear left corner of the Studio A live area. Marvin Gaye, playing piano, would have been in the near left corner, and to his right would have been Robert White on guitar. James Jamerson normally played bass while standing in front of the DI, but in this case his positioning was apparently a little different.

In the book Standing In The Shadows Of Motown: The Life & Music Of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson, written by one Dr Licks, Dave Van DePitte — who arranged the entire What's Going On album — stated that "Jamerson always kept a bottle of [the Greek spirit] Metaxa in his bass case. He could really put that stuff away, and then sit down and still be able to play. His tolerance was incredible. It took a hell of a lot to get him smashed.”

Well, smashed Jamerson apparently was when he arrived at Studio A after Gaye had located him playing in a local club and asked him to drop by once the set was over. Too drunk and tired to sit upright in a chair, he lay down on the floor and, after taking a look at Van DePitte's chord charts, played the chromatic, syncopated, constantly‑changing bass line that still captivates legions of admirers.

As Van DePitte would recall, "He just read the part down like I wrote it. He loved it because I had written Jamerson licks for James Jamerson.” The bassist's wife, Annie, also remembered him returning from the session and describing 'What's Going On' as a masterpiece; a notable display of enthusiasm from a man who rarely discussed his work with her.

Overdubs

Meanwhile, after Steve Smith completed his work on the song, Ken Sands sat behind the console for the overdubbing and layering of assorted parts: the tambourine and percussion provided by Jack Ashford; the bongos and congas of Eddie 'Bongo' Brown; and, of course, Marvin Gaye's lead vocal — in this case, a double vocal that resulted not from a mistake (as has been reported elsewhere), but from the singer capitalising on a Sands decision that, unwittingly, would result in Gaye's trademark sound, layering as many as three lead vocals on his subsequent recordings.

"We recorded two lead vocals that Marvin wanted to compare with one another when each was incorporated into the track,” Sands explains. "He wanted me to make him two 7.5 ips copies that could be played individually, but instead of doing that I made him one stereo 7.5, with the entire track in the centre of the mix, the first vocal on the left hand side and the second vocal on the right. This was to be expeditious, so he could listen to them simultaneously or against each other. As it turned out, singing against himself worked, but I'm not going to take credit for thinking things through and saying, 'This is what I want to happen'. It just happened. That's how a lot of things happen. A lot of brilliance is bred of happenstance.

"At that time, Mike McLean had converted both studio facilities from tube‑type microphones to solid-state mics, so for lead vocals we used the Neumann U87, which is the solid-state version of the U67. Marvin took his time doing his vocals and he'd often come back and try a different approach. For 'What's Going On' he did the vocals in Studio B, wearing his knitted skull cap, and everything went very smoothly.”

While Gaye added his own backing vocals in the form of the "what's going on” refrain, he also recruited his Detroit Lions friends Mel Farr and Lem Barney to contribute party‑like background chatter alongside some of the Funk Brothers. On the other hand, Eli Fountain's alto sax intro wasn't part of Gaye's original vision, but he loved the hook and responded to Fountain's assertion that he was "just goofing” by telling him, "you goofed off exquisitely”.

'What's Going On'

The result, after Ken Sands took care of the mix, was a protest song like no other that had come before; a number that, rather than ask "what's going on,” answered this by reporting on America's struggles and Marvin Gaye's personal strife without bitterness or anger. In a relaxed, laid‑back manner that exuded empathy and understanding, Gaye addressed a "father, father” in reference to his troubled relationships both with God and the patriarch who would eventually kill him, and reached out to the "brother, brother, brother” as an appeal to not only his Vietnam vet sibling Frankie, but all of humankind.

"You see, war is not the answer, For only love can conquer hate,” Gaye intoned, blending the vocal spirituality of his gospel roots with the soulfulness and warmth of the song's sax breaks and jazz‑flavoured rhythms, but this didn't impress Berry Gordy. On the contrary, denouncing 'What's Going On' as "too jazzy”, after Gaye presented it to him with the religiously‑infused B‑side 'God Is Love', the Motown CEO refused to issue the single.

The possibility that Gaye's political statements might alienate certain white listeners can't have been Gordy's primary concern — earlier in 1970, he had approved the release of Edwin Starr's 'War' and the Temptations' 'Ball Of Confusion' (mixed by Ken Sands with producer Norman Whitfield). Quite simply, he just didn't like 'What's Going On', telling Harry Balk — who had sold his Impact and Inferno labels to Motown before running its Creative Division — that it sounded "old” and that he hated its "Dizzy Gillespie‑styled scats”.

Marvin Gaye responded by refusing to record any other material until 'What's Going On' was released, and when Gordy asked Smokey Robinson — then Motown's Vice President, as well as one of its biggest stars — to persuade the Prince of Soul to change his mind, Robinson informed him that, "like a bear shitting in the woods, Marvin ain't budging.”

The stalemate lasted several months until January of 1971, when Harry Balk pushed for the single's release. Quality Control's Billie Jean Brown disagreed, so they turned to Vice President of Sales Barney Ales, who sided with Balk, resulting in 100,000 copies being pressed and promo singles being mailed to radio stations. Gordy was placated when the former sold out within 24 hours, leading to the pressing of a further 100,000 discs to meet demand and 'What's Going On' hitting the top spot on the R&B chart that March. Reaching number two on the Billboard Hot 100, it ended up shifting over two‑and‑a‑half million units, making it the fastest‑selling release in Motown's history up until that time.

By then, predictably, Berry Gordy had commissioned the recording of an entire album to cash in on the single's success. Ken Sands took care of the strings and brass on those sessions alongside David Van DePitte in Studio B, while also recording the lead vocals and some of the backing vocals. The rhythm section and other parts were tracked at Studio A, Detroit's United Sound Studios and The Sound Factory in West Hollywood before, according to Sands, he did the final mix on the tenth floor of the Motown Center. Completed in May 1971 and released that same month, What's Going On was the first of Marvin Gaye's albums to afford him credit as sole producer.

"Steve Smith did a couple of mixes and I did the final one,” Sands recalls, contradicting the conventional wisdom that, after he arrived in LA for a film project, Gaye scrapped 'The Detroit Mix' and remixed the album to give it an even softer, smoother feel. "It was my mix that I heard on the radio,” Sands insists, "and that was my final assignment for Motown before the company relocated to the West Coast.”

Either way, What's Going On remained on the Billboard Top 200 for over a year, selling more than two million copies, while being named 'Album Of The Year' by Rolling Stone, which, in 2003, would rank it number six on its list of the '500 Greatest Albums Of All Time'.

Goodbye To All That

Not that the project's success could sway Ken Sands to up roots and join Motown on its cross‑country trip.

"My first wife didn't want to leave her family and friends in Detroit,” he explains. "So we stayed here... and then later we divorced. Still, I can't complain. I am a blessed man. We could do no wrong at Motown and I looked forward to going there every day, because I'd be anxious to know what was happening with a particular tune, get feedback about what I'd just done or learn who, in Berry's eyes, was going to be higher on the totem pole. It was exciting to work there. I was feeling my way around, too, but I was blessed enough to work with some of the best professionals in the world, ranging from the artists, songwriters, producers and engineers to the promotion and marketing people.

"I mean, where else could I have been paid $90 for playing a rhythm pattern on my stomach for Diana Ross & the Supremes' 'Shadows of Society'? Brian Holland had done that on the back of a chair for a couple of tunes back in the early '60s. So when [songwriter] Jack Goga said he wanted that sound when I was mixing the Cream Of The Crop album, I went out to the studio, beat on my stomach with my cupped hands and was rewarded with a union cheque. My stomach is famous!”

Echo, Motown Style

Ken Sands: "When I worked there, Motown was a college of musical knowledge for whoever was producing, writing and engineering. It was at Motown that I learned about engineering. Mike McLean taught me a lot via his attention to detail regarding microphones, amplifiers and speaker equalisation — he was a fanatic when it came to speaker equalisation and he had an awful lot to do with the way Motown sounded. So did the echo chambers.

"The chambers were in the attic of the houses at 2648 and 2652 West Grand – in fact, they were the attic; rooms with wet‑plaster walls and floors that were shellacked so that they were really, really hard. Mike would put mid‑range drivers, high‑frequency drivers and Shure SM57s in these chambers to accentuate the mid‑range and the high‑end; the kind of echo that you hear on the Supremes' 'Where Did Our Love Go'. That was the new, silky, longer‑delayed, trebly kind of chamber sound that Mike came up with, equalised individually for crispness, and it was a huge part of the Motown Sound that was still being employed by the time we recorded 'What's Going On'.

"In fact, those echo chambers were sent and received via an equalised telephone line to the Motown Center mixing rooms. Larry Miles would mix in the mono room and I would mix in the stereo room, and we had access to the echo chambers that were on the Boulevard. In the Hitsville USA building at 2648 — now the Motown Museum — there's a hole cut in the upstairs ceiling that you could yell into and hear the echo return. It was quite a place...”