If you want real musicians playing your composition but have no idea how scores should be presented for them, you can still make playable Logic parts with our simple guide.

Your orchestral MIDI track is coming along really well. You've spent hours playing in or entering MIDI information, and it sounds as convincing as it's possible to make it sound using samplers and software instruments, but it's not quite there yet — there's something missing. You feel it's lacking the authenticity of real instruments played by real players. This song is just too good to rely on MIDI: it needs a human touch and you decide that it's time to ship in a bunch of musicians as the icing on the cake. But musicians are going to need musical parts to play from, and you've never used Logic in this way before. What now?

Starters

If you can get the notes into the correct key and onto the stave in a neat and tidy manner, you'll be a long way towards achieving your goal. Let's have a look at how to turn the MIDI regions you have in your Arrange window into usable, playable, printed parts for the scrapers, blowers and thumpers when they turn up at your studio.

In this instalment we will start work on producing parts for a brass section (often referred to as a 'horn' section) and doing some basic formatting. The techniques I'll discuss in this section can then be applied to other solo instruments, such as flutes, basses and violins.

For this article a 'part' will be an individually printed piece of music for a musician to play from (for example, first trumpet or flute). A 'score' is the rather larger object that a conductor or producer would use to oversee all the individual parts and when they should be playing.

I have found that producing parts in Logic for musicians can be fairly quick and easy if you do things in the optimum order. In addition, there are some handy tips and tricks that can help in simplifying and speeding up the process.

The First Step

My first step is to save a new copy of the song file, renaming it something like 'mysongfilePARTS.iso'. I do this to reduce the risk of permanently altering my actual song file, to which I will ultimately record the real instruments. For safety's sake, having a copy to work on seems the best way to be sure you can always get back to your starting point. Even if you lose or ruin a part while experimenting and tweaking, you can always cut and paste from the original.

In the Logic manual you will read that there are a number of tools that can be used to produce printed parts without affecting the real-time playback of your MIDI data. We will have a look at these later, but for now let's look at the technique that I use for most of the time: deliberately affecting the MIDI playback of the song in order to achieve the best printed results.

Preparing Your MIDI Tracks

Let's assume that today's task is to produce printed parts for a four-piece brass-section. Our section will consist of two trumpets, an alto sax and a trombone. Before embarking on the actual score production there are a couple of tasks that you should complete in preparation.

An unmerged region, as shown above, will leave blank spaces between the played sections on your printed part. Use the Merge command to create one region (shown here) and, with respect to your score, empty bars instead of blank spaces. This makes it much easier for your players to follow.

An unmerged region, as shown above, will leave blank spaces between the played sections on your printed part. Use the Merge command to create one region (shown here) and, with respect to your score, empty bars instead of blank spaces. This makes it much easier for your players to follow.

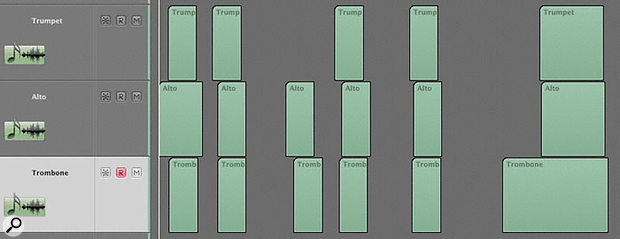

You may have fragmented regions of MIDI information for each of your brass instruments, where you have played in just the bits you need throughout the song. Make sure that on each separate track you have merged the brass regions into one single region. Do this by highlighting all the regions on a track and using the Merge command (Region / Merge / Regions). If you don't have a single region, your printed part will end up with blank spaces rather than empty bars between the played sections.

Next, still in the Arrange window, if there is a chance that you will ever want to use these parts live, make sure that the brass regions run from the very start of the piece to at least where your guys will finish playing, if not to the end of the piece. Drag the left-hand edge of each region to start at bar 1 1 1 1 (assuming this is the first bar of the piece), and, if necessary, elongate the right-hand edge to the end of the song. Do this for each of your brass-section tracks. If your section don't start playing until bar 68, you can start the regions nearer there, but starting these parts at the beginning can help the players with their orientation.

Splitting Your Parts

Usually you will need a separate printed part for each 'voice' or instrument of your section. You may have one region with what could be all four parts within it. You may, as above, have two trumpet parts in a single region on a track (as they are using the same sound source), the alto on its own track and the trombone separately. So you have three brass tracks for four parts.

To have these played by your real brass section you will need to produce an individual part for each of the brass players: the first trumpet (usually the highest part), the second trumpet (the remaining next lower part), and the alto sax and trombone third and fourth respectively. All solo/single-note instruments such as brass, woodwind/reeds and strings (first violin, second violin and cello, among others) will require this sort of treatment, as their players are not like pianists, who can read and will play multiple parts from one stave.

To extract two parts from a single region, first create another trumpet track below the first in the Arrange window. Copy the trumpet region onto this new track so that you have two identical regions on two tracks. This will force the score into providing another stave below the first. This gives you the separation that will be required for printing.

Work through the first region deleting the lower (second trumpet) part, then work through the second region deleting the first trumpet part, thus leaving different parts on two channels and resulting in four brass-section parts ready for action. Now that you're into recording real instruments, you could consider recording the MIDI data on separate tracks as you write your orchestration. This will reduce the likelihood of problems when you're at the stage of printing the parts.

Stream, Beam & Broadcast

Rogue Amoeba's excellent Airfoil software, which allows you to stream any audio from your computer using Apple's Airport Express, has been updated to version 3. It can now transmit audio to wireless-enabled devices, such as other computers, Internet radios and Apple TV. I've been using it to beam audio from the G5 in my studio to laptop speakers and a TV sound system — it's very convenient not to have to burn a CD every time you want to check a mix. Using an additional FM transmitter (costing just a few pounds from eBay), I can also hear how my mixes sound through both transistor and car radios. So many professional mixing engineers have told me they check their mixes in the car that I've started to wonder why recording studios aren't built inside automobiles! Airfoil also synchronises video with audio, so you can choose to watch movies on your laptop while listening to the audio wirelessly through an Airport-enabled hi-fi. I recently mastered some tracks through the stereo in my living room using Airfoil. I used Logic's linear EQ and compressor to master, and acheived excellent results — it's the system I know the 'sound' of best. The latency means that you have to wait a second or so for any parameter change to be recognised, although it isn't too much of a trial even for an inveterate knob twiddler like myself, and it means that I spend more time reflecting over each change rather than moving on to the next frequency too soon.

If you co-produce with people in different geographical locations, it can be a real pain to keep sending off MP3s of mixes for evaluation. Believe me, when you've emailed 25 versions of a track in a single afternoon to California, it doesn't feel as though technology makes things any easier! Rogue Amoeba have come to the rescue again with Nicecast. This utility is designed to let you set up your own Internet radio station, and can allow distant colleagues to hear any mixes in real time, so that conversations (and blinding rows!) can be conducted via Skype or iChat. In addition, the company's web site states that you can use Nicecast to broadcast 'live events'. I've been using it to send audio over the Internet in real time and, as long as your bandwidth is sufficient, it works pretty well. There is also the added benefit of being able to distribute your finished music via your own radio station.

Airfoil costs a mere $25 ($10 to upgrade from version 2), while Nicecast is $40. Both are available from www.rogueamoeba.com. Stephen Bennett

Tidying Your Parts

If you have created a 'natural' sounding performance by 'humanising' your MIDI information, or you have played it in from a keyboard 'freestyle', rather than having it perfectly quantised, you will need to produce parts that look as though you've quantised them and played them like a computer, in order to get your musicians to play them how you want to hear them — like humans!

As you are using a copy of your original song file, you should be able to quantise each part in the Piano Roll (Matrix). This is the simplest way of tidying up the part, but make sure, even though it'll sound computerised, that it's still playing the notes in the correct places, with no strange overlaps or chords.

A quantise setting of16,24 stops the score from displaying anything smaller than 16th notes (semiquavers)while still showing 16th-note triplets.

A quantise setting of16,24 stops the score from displaying anything smaller than 16th notes (semiquavers)while still showing 16th-note triplets. A setting of 32,24 allows up to 32nd notes (demisemiquavers) to be displayed, while also still showing 16th-note (semiquaver) triplets.Alternatively, you can go into the Score window and use Logic's special score quantisation options to tidy up. This quantise differs from that found in the Piano Roll, as it doesn't affect the playback of the MIDI information, just the visual position of the notes on the printed part. This is a 'quick fix button' and it does work in most instances.

A setting of 32,24 allows up to 32nd notes (demisemiquavers) to be displayed, while also still showing 16th-note (semiquaver) triplets.Alternatively, you can go into the Score window and use Logic's special score quantisation options to tidy up. This quantise differs from that found in the Piano Roll, as it doesn't affect the playback of the MIDI information, just the visual position of the notes on the printed part. This is a 'quick fix button' and it does work in most instances.

Select the part you are working on, open it in the Score window and select the stave by clicking on the lines (not notes or clefs) so that the lines turn blue. Click on the quantise box situated under the top bar of the left column and bear in mind that any setting chosen here will affect the whole of the selected part from start to finish, but will not alter the MIDI playback.

There are many generic quantisation settings available, most of which you will recognise from previously working with MIDI. However, there are extras specifically for score writing that allow for two types of quantisation at the same time, such as '8,12' and '16,24'. For example, using 8,12 stops the score displaying anything smaller than eighth notes (quavers), while also allowing eighth-note triplets. Similarly, 16,24 allows nothing smaller than 16th notes, while also still showing 16th-note triplets. These settings take a bit of working with to be sure of the correct one, so experimentation is the best way forward; you're looking for the neatest result, and the setting that works for one part may not work for another, depending on its content.

Another method for neatening your MIDI parts involves the quantise tool from the Score window toolbox. (This can be useful if you only have a few notes obviously out of place.) Select the tool, click and hold individual notes that are wrongly represented, and then apply the quantise value you require. This can be hit and miss, depending on where you want the note to be positioned and where Logic wants the note to go. Also, this tool does affect the MIDI position, as it works the same way as in the Piano Roll, so be careful if you're not using a copy of the song file.

The most reliable way that I have found of getting around quantising issues is to use a combination of the above methods, by working with the Piano Roll (Matrix) open at the same time as the Score window (setting up a new screen set allows for quick access). Now adjust the notes on the Piano Roll, selecting them individually or in groups and dragging them minutely in the direction they need to go, until they are in the correct places on the score. This way you have the visual grid of the Piano Roll to refer to, and by using Ctrl+shift+drag to move notes you can see that the tiniest movement can have the desired effect on the part.

Although the editing process I've just described definitely affects the MIDI playback, it does give you a good chance of getting just what you need on the printed part — this being the main reason I use a copy of the song file to do the score work on. It can also mean that you end up using much smaller overall score-quantise values without compromising readability for the musicians and, as a result, can speed up your preparation. Additionally, it's possible to lengthen and shorten notes within the Piano Roll more easily than you can in the Score window.

How Are We Doing?

Once you have been through all four of the brass regions using some or all of the techniques above, you should have a fairly accurate set of parts ready to print for your blowers. At this point you haven't added any 'markings', such as those for dynamics, articulation and speeds, but as mentioned earlier you can talk this through with your guys when they arrive. I suggest you give them their parts, play them the original track so that they can follow the music, and then discuss with them the way you want things played.

There are further formatting options available to embellish your newly created parts, such as Key Signatures, Time Signatures and Transposing, and I'll take you through these in greater detail next month.

Interpretation, Syncopation, No Overlap ... What?

At the left side of the score window you will see three tick boxes: Interpretation, Syncopation and No Overlap. These are a very useful set of general formatting tools that visually affect the whole of the part that you are working on.

Interpretation tries to show the part in its simplest form by lengthening note values (visually — not the MIDI data itself) to reduce the number of little rests that appear between notes that you may have played slightly short. This makes the part clearer and smoother to read. The two examples below show a score with Interpretation both ticked and un-ticked, the un-ticked version shown above and the smoother, ticked version shown below.

Interpretation tries to show the part in its simplest form by lengthening note values (visually — not the MIDI data itself) to reduce the number of little rests that appear between notes that you may have played slightly short. This makes the part clearer and smoother to read. The two examples below show a score with Interpretation both ticked and un-ticked, the un-ticked version shown above and the smoother, ticked version shown below.

No Overlap does as it says, by not allowing the score to show overhanging notes that may have been played in the MIDI track. Often, to get a solo line sounding really smooth, you will have let notes hang on longer than they should, overlapping in order to get the effect of a smooth transition. The two examples to the right show this, with the first example containing adjoining notes that will appear on the score without the use of No Overlap. The score would view this as a chord rather than a solo line. Clicking the No Overlap box should help to rectify this for you, without your having to go through the MIDI data and shorten all the troublesome notes.

Syncopation is a term for notes that are played away from the main beats of the bar, or off-beat. Computers like to see things their way and humans theirs, so the Syncopation box tells Logic to show the syncopated sections in a more easily read, less cumbersome manner. Sometimes, however, it produces syncopated passages that, though technically correct, don't quite show up the way humans would write them using the 'rules of theory of music'. So when you use this setting, be prepared for neither ticked nor un-ticked to be completely correct for your musicians. I find that musicians are quite used to this, as computer-printed music is common these days, and they adapt pretty quickly.