Ikutaro Kakehashi, founder of Roland, at the 1964 NAMM show with the Ace Electronics R1 and Canary.

Ikutaro Kakehashi, founder of Roland, at the 1964 NAMM show with the Ace Electronics R1 and Canary.

The Roland name is almost synonymous with music technology — there can't be an SOS reader who hasn't made use of their instruments at some time. As founder Ikutaro Kakehashi approaches his 75th birthday, we begin a journey through the company's extraordinary history...

I think that it was one of the staff who wrote for Roland's in-house magazine in the 1980s who first posed the question, "What have the Rolands ever done for us?", with apologies to John Cleese. The Judean Peoples' Front (or was it the Peoples' Front of Judea?) might well have replied as follows...

Activist 1: "The Jupiter 8?"

Stan: "What?"

Activist 1: "The Jupiter 8."

Stan: "Oh yeah, yeah... they did give us that, that's true."

Activist 2: "And the Space Echo."

Activist 1: "Oh yeah, the Space Echo... remember what echo units used to be like?"

Stan: "Yeah, all right, I'll grant you that the Jupiter 8 and the Space Echo are two things the Rolands have done."

Activist 3: "And programmable rhythm units."

Stan: "Well, yeah. Obviously programmable rhythm units, programmable rhythm units go without saying, don't they... But apart from the Jupiter 8, the Space Echo, and programmable rhythm units?"

Activist 2: "Boss effects units?"

Activist 1: "Guitar synthesis?"

Activist 4: "Playable electronic drum kits?"

Stan: "Yeah, yeah, alright... fair enough."

Activist 1: "... and sample-based synthesis."

Activist 4: "Yeah, yeah, that's something that we would really miss if the Rolands left."

Activist 2: "Jazz Chorus amplifiers..."

Activist 1: "And they made analogue synthesizers that were reliable!"

Activist 3: "Yeah, they certainly know how to keep things working. Let's face it, they were the only ones who could in the 1970s..."

Stan: "All right, but apart from the Jupiter 8, guitar synthesis, sample-based synthesizers, playable electronic drum kits, Boss effects units, programmable rhythm units, reliable analogue synthesizers, the Space Echoes and Jazz Chorus amplifiers, what have the Rolands ever done for us?"

Activist 5: "...MIDI?"

Stan: "Oh, shut up!!!":

Clearly, the Rolands have done a great deal for us, and it seems high time that we looked back at some of the milestones in the company's (and, therefore, the electronic music industry's) history. But this is the story of a man as much as a company, so we'll start by turning our clock back to a time long before the birth of the hi-tech music.

Milestone: The Ace Tone FR1 Rhythm Ace

Ace Electronics' successful FR1 Rhythm Ace.

Ace Electronics' successful FR1 Rhythm Ace.

It's hardly surprising that the FR1 was successful. Long before rhythm machines became commonplace, it offered 16 preset patterns that you could mix together simply by pressing two buttons simultaneously, so more than one hundred rhythm combinations were just a button press (or two) away. What's more, four additional buttons allowed you to defeat the cymbal, claves, cowbell and bass-drum sounds, thus allowing you to modify the sound still further.

But perhaps most innovative of all were the FR1's sounds, now recognisable as archetypically 'Roland', and which were later destined to shape rock and pop music from the late '70s onwards. Indeed, the FR1 is the precursor of all Roland's great analogue rhythm machines. What's more, in an era of sometimes shoddy manufacturing and poor reliability, the FR1 was built like a tank, and also to last. Mine is approaching its 40th birthday, and its little heart beats as strongly today as it did back in the Summer of Love.

Watches & Other Beginnings

Born in 1930, Ikutaro Kakehashi was just two years old when his parents died from tuberculosis, and he spent much of his youth living in Osaka under martial law. He studied mechanical engineering and simultaneously worked as a schoolboy worker in the Hitachi shipyards where Japan's 'midget' suicide submarines were built. As a result, he witnessed a great deal of destruction in the last months of the war.

Once World War II was over, and after failing on health grounds to enter the city's university in 1946, Kakehashi moved to the southernmost of Japan's four major islands, Kyushu. This offered a far more rural existence and, to survive, he took a day job as a geographical survey assistant. But, at just 16 years old, he noticed that, with no watch or clock industry in post-war Japan, there was a thriving business to be had repairing existing timepieces. He was unaware of it at the time, but a chap named Torakusu Yamaha had also started out as a watch repairer, as had Matthias Hohner. Even the Hammond Organ Company started out as a sub-division of the Hammond Clock Company!

Kakehashi was offered a part-time position in a watch repair business, but after a few months he had to leave when he asked to be taught everything in a few months, thus attempting to short-circuit the traditional seven-year apprenticeship.

In response, Kakehashi bought a book on watch repair and set up the Kakehashi Watch Shop in direct competition with his former employer. This was a success, and he next decided to turn his enthusiasm for music into a business venture. It was no longer illegal to own a short-wave radio or to listen to foreign broadcasts and, scanning the airwaves for new music, Kakehashi learned the basics of how radios worked. He was soon cannibalising broken sets to create working ones, and his repair shop started handling broken radios in addition to watches and clocks. Nonetheless, he still supplemented his income with agricultural work.

Kakehashi spent four years in Kyushu, but when he heard that he could go back to Osaka, he liquidated his business to fund his entry into the city's university. Still just 20, he returned but was struck down by tuberculosis in both lungs, the treatment for which quickly consumed all the money he had earmarked for his education. So, as the months in Sengokuso hospital turned into years, Kakehashi supported himself by repairing watches and radios for the staff and other patients.

At this time, Japan was about to broadcast its first television signals, and Kakehashi was determined to receive the first test transmissions. He borrowed enough money to purchase a cathode-ray tube and, still confined to hospital, assembled his own receiver. Amazing though this was, it is almost incredible when you understand that Kakehashi had by this time spent three years in hospital. Indeed, his condition was gradually becoming terminal when he was selected as a guinea-pig for the newly developed drug, Streptomycin. Kakehashi's improvement was immediate; within a year he had left hospital. In retrospect, he was extremely lucky... the cost of Streptomycin was such that he could never have afforded it, and had he not been selected, it's likely that he would not have survived.

Everything About Electric And Electronic Instruments

In the 1960s, Japan had strange patent laws that allowed foreign manufacturers to import and patent technology even if it were in the public domain in other countries. This loophole, caused by a need for prior Japanese publication of a given idea, was a severe impediment to the fledgling Japanese manufacturers of the time. So Kakehashi and 16 colleagues (including Tsutomu Katoh, President of the Keio Organ Company, later to become Korg) collated all the information they could, and in January 1966 published two books: Everything About Electric Instruments and Everything About Electronic Instruments. This stopped foreign manufacturers from patenting anything except genuinely new ideas and techniques, thus allowing Japanese companies to design and build products using technology in the public domain, and thereafter to improve upon it.

The two books became the first Japanese reference books for electric and electronic musical instrument design.

The Ace Years

In 1954, unable to find employment, Kakehashi opened an electrical goods and repair shop which he named Kakehashi Musen ('Kakehashi Radio'), and this grew rapidly over the next six years. He changed the name to the Ace Electrical Company, and was soon employing around 20 staff. But as early as 1955, he had decided to branch out, combining his electrical skills and his interest in music to develop products for the music market. Like Bob Moog in the USA, his aim was to produce an electronic instrument capable of producing simple monophonic melodies, so he started by building a Theremin. However, he was disappointed to find how difficult this was to master. Later, exposure to an Ondes Martenot convinced him that a keyboard-based instrument was more likely to be successful, so he built a four-octave organ using parts from a reed organ, bits of telephones, and simple transistor oscillators. Kakehashi admits that Prototype No. 1 sounded rather different from how he had hoped, so it never entered production.

In 1959, he designed and built a Hawaiian Guitar Amplifier, but he also persevered with his organ developments, and, in 1960 — the year in which he founded Ace Electronic Industries — he designed an organ that was to become the Technics SX601. Sure, his contact with Matsushita (who owned the Technics brand name) came courtesy of a friend of a friend, and it was unlikely that Ace could have raised the capital to manufacture and distribute the instrument, so Kakehashi must have leapt at the chance. Nonetheless, the birth of the SX601 was no small achievement, and Ace Electronic were up and running as a manufacturer of musical equipment. Three years later, in 1963, the company added guitar amplifiers to its product range, but Kakehashi's ambitions lay elsewhere...

Ace Electronics' first commercial product, the unsuccessful R1 Rhythm Ace.

Ace Electronics' first commercial product, the unsuccessful R1 Rhythm Ace.

Like Tsutomu Katoh, the man who founded Korg in 1963, and whose life has in some ways paralleled his own, Kakehashi was intrigued by early electro-mechanical percussion instruments such as the Wurlitzer Sideman. So, in 1964, he developed the Ace Electronics R1 Rhythm Ace, and took it — along with the Canary, a simple monophonic instrument heavily influenced by the Clavioline — to the NAMM show in Chicago. The Rhythm Ace was possibly the world's first fully transistorised rhythm machine but, despite interest and sample orders from American manufacturers, Kakehashi did not seal any manufacturing or distribution deals.

The reason for the failure of the R1 is obvious; it produced sounds when you pressed buttons, much like today's drum pads, but it offered no pre-programmed patterns. The technological problems of producing repeating rhythms were themselves non-trivial, but Kakehashi and his colleagues overcame them by inventing a 'diode matrix' that determined the position of each instrument in a pattern. Having done so, they were able to release the FR1 Rhythm Ace, which appeared in 1967 (see the above box). The positive response was immediate, and the FR1 was adopted by the Hammond Organ Company for incorporation within its latest line of organs. Ace Electronic were on their way...

The relationship between Hammond International (the worldwide distributor of the organs built by the Hammond Organ Company) and Ace was a good one and, soon after they embarked upon their technical collaboration, Ace became the Japanese importer and distributor for Hammond organs. The following year (1968) the companies formed a joint venture called Hammond International Japan, and in 1969 Kakehashi raised the capital to take over a derelict piano and organ manufacturer, Zenon Gakki Seizou, in Hamamatsu. This factory was soon to become a major source of Hammond organs and, of course, the sole source of Ace Tone organs.

By this time, Kakehashi and his team were heavily involved in designing new guitar amplifiers and effects units as well as rhythm machines, but it is perhaps for their combo organs that Ace are best remembered. These included the TOP3 (1965), the TOP1 (1969), TOP5, TOP6, TOP7, TOP8, and TOP9, plus the more complex, dual-manual GT7. Of these, the GT7 is the most interesting, because it appears to be the direct precursor of the Hammond X5. Furthermore, it was perhaps the only Japanese organ to use sine waves as the building blocks of its sounds rather than the brighter sawtooth and pulse waves favoured by the likes of Lowrey, Baldwin, Wurlitzer, Vox, and, indeed, all previous Ace instruments.

In 1971, Kakehashi became involved in a highly secretive development that Hammond codenamed Mustang. The project was later unveiled at the NAMM show in Miami, and the Piper Organ — the world's first single-manual organ to incorporate a rhythm accompaniment unit — became one of the most successful products ever produced by Hammond.

Unfortunately, continued infusions of capital eventually diluted Kakehashi's shareholding in Ace Electronics to the point where he had become a minority shareholder in his own company. This had not been a problem when the major investor was a company named Sakata Shokaim, because Kakehashi and Kazuo Sakata shared an interest in organs, and enjoyed a good professional relationship. Unfortunately, an industrial company, Sumitomo Chemical, accidentally acquired Ace when it purchased Sakata Shokai. Sumitomo's staff had no understanding of or sympathy for the music industry, and Kakehashi found the situation intolerable so, despite 18 years of hard work and commitment, he decided to resign and walk away. He did so in March 1972, leaving Ace Electronic — by now a company with a turnover approaching $40m per annum — and Hammond International behind. It was time for something new.

1972 MAJOR PRODUCT LAUNCHES

EFFECTS

- AF100 "Bee Baa" Fuzz & Treble Booster.

- AS1 sustain pedal.

RHYTHM PRODUCTS

- TR33.

- TR55.

- TR77.

1972 — The Birth Of Roland

Just a month later, on 18th April 1972, Kakehashi established the Roland Corporation. However, he did not choose the name because of the French romantic poem, Chanson de Roland. This is an oft-repeated story repeated in dozens of places on the Internet. In fact, Kakehashi chose the name for phonetic reasons: he wanted two syllables with soft consonants, and Roland satisfied his criteria nicely.

Almost immediately after establishing the company, Kakehashi received an offer from the Hammond Organ Company; they wished to buy a 60-percent shareholding in the new business. However, he had no wish to be the junior partner in his own company for a second time, so he decided to forge ahead on his own.

Roland started life in a rented shed, with funds of $100,000 and seven staff culled from Ace Electronics, but neither products nor customers. Using his considerable reputation as collateral, Kakehashi managed to persuade parts suppliers to offer 90-day payment terms, and then aimed for the unbelievable target of designing, manufacturing, and exporting a rhythm unit before the bills fell due. The decision to export was not as strange as it may seem. The dominance of Yamaha and Kawai in Japan's music markets made it impossible for Roland to compete if the new company launched an established type of product, and it was unlikely that an innovative product could make an impact in time for Roland to earn enough cash to survive. Therefore, foreign markets offered more hope, provided that Kakehashi could find distributors capable of delivering Roland products across the key markets of the USA and Europe.

Kakehashi travelled first to Canada to obtain orders for his as-yet non-existent rhythm unit. Next, he visited the Multivox Corporation in New York, the US importer for Ace products (and the company which, somewhat later, would be linked to the somewhat cloudy Multivox copies of Roland instruments). In Europe, he contacted Brodr Jorgensen, a Danish company that had subsidiaries in the UK, Switzerland and Germany, and which distributed Ace across the continent. In each case, he obtained orders for a number of units, sufficient for him to start purchasing components and undertake assembly.

Although Kakehashi lived in Osaka, and Roland were established there, he had had extensive business dealings in Hamamatsu in his Ace days, and was convinced that this was the right city in which to manufacture Roland products. Consequently, he rented a small factory there, and production of Roland products started in both locations. Roland were later to move in their entirety to Hamamatsu, establishing a number of factories in the area, but for the first few years, Kakehashi would commute overnight by train between the two.

The first Roland product, the TR77 rhythm box.

The first Roland product, the TR77 rhythm box.

Roland's first product was the TR77, one of three short-lived rhythm boxes; the TR33, TR55 and the TR77 itself. This is not surprising; Kakehashi had extensive experience in designing such products, the development cycle was short, and the costs were low. The organ-industry heritage of these products was obvious, and the TR33 had the cut-out body shape that showed that it was intended for mounting underneath a piano or organ keyboard. The TR55 was more of a tabletop design, but the long, flat TR77 (which was, if truth be told, little more than an updated version of the Ace Tone FR7L) was the pick of the bunch. It allowed you to merge rhythms, it offered two- and four-beat patterns that you could superimpose on the more traditional Latin and other patterns, it had a very nice fade-out feature, and there were independent volume sliders for the kick drum, snare, guiro and maracas/cymbals/hi-hat. When Hammond rebadged the TR77 as the Hammond Rhythm Unit, it was clear that Kakehashi had made the best use of his contacts, and that Roland were on their way.

Alongside these, Roland also continued to develop effects units. The first of these were the AF100 Bee Baa (a fuzzbox with four knobs on the rear panel, perfectly positioned for maximum awkwardness) and the AS1 Sustainer, the ancestor of today's compression/sustain pedals. In October 2003, I saw a Bee Baa for sale in Canada, with a price tag of C$500 plus tax, which at the time was about £250. Given the unit's rarity, I could understand the shop's desire to cash in on it, but as for the sound... The most polite one can be is to say that it wasn't worth £250.

Milestone: The Roland SH1000

The first Roland synth, the monophonic SH1000.

The first Roland synth, the monophonic SH1000.

Roland's first synthesizer was Japan's first synthesizer, predating the Korg 700 by a handful of weeks. It was a strange instrument, offering 10 preset tones to which you could add vibrato, growl and portamento. Alternatively, you could select any combination of eight waveform/footage options ranging from a 32' sawtooth to a 2' square wave, plus noise, and shape sounds using the envelope generator, some preset envelope shapes, a self-oscillating resonant filter, and modulation.

At the time, the fat, punchy patches of Moogs and ARPs were the preferred sounds of a generation, so the little Roland was considered weak and uninspiring. What's more, it lacked any redeeming qualities such as pressure sensitivity, performance controls, duophony, a spring reverb, or interconnectivity with other synths, all of which had appeared on other manufacturers' instruments over the previous three years.

Nonetheless, two things made the SH1000 special. Kakehashi understood that electronic music products needed to be affordable and reliable as well as creative. So he designed his synthesizer to use fewer op-amps than other synths, and this enabled him to reduce the cost considerably. The yen/dollar exchange rate then made it possible for Roland to sell the SH1000 for around US$800, which was a fraction of the price of Moog and ARP synths. Secondly, the SH1000 was well built, and it exuded reliability. At the time of writing, mine is almost 30 years old, but looks as good as it did the day it was built, and still performs faultlessly. All of the knobs and slider heads are present and correct, without a single crackly pot to indicate the instrument's age. It has never needed tuning or servicing either. If anything justifies Roland's ensuing success, it is this.

1973 MAJOR PRODUCT LAUNCHES

EFFECTS

- AD50 Double Beat fuzz/wah pedal.

- AG5 Funny Cat distortion/sustain pedal.

- AW10 wah pedal.

- RE100 tape echo.

- RE200 tape echo.

PIANOS

- EP10.

- EP20.

SYNTHS & HI-TECH

- SH1000 monosynth.

- SH3 monosynth.

1973

Roland's turnover in their first year was remarkable; $300,000 was not a trivial sum in the early 1970s. However, the problems Kakehashi faced as he tried to grow the company were not inconsiderable. Establishing domestic and export markets is hard enough without your former employer trying to block your efforts to create a distribution channel, but this is what Ace did, threatening to disenfranchise any dealership that carried Roland products. Fortunately, most refused to be bullied, and Kakehashi was able to continue marketing and selling his products in Japan, North America and Europe.

The following year was to see a number of product launches that — with Roland's distribution network in place — would cement their position in the marketplace. Least amongst these were the AW10 wah pedal, the more advanced AD50 Double Beat (which, by virtue of combining wah, fuzz and a simple phaser, was possibly the ancestor of all today's multi-effects pedals), and the AG5 'Funny Cat' auto-wah. Then there were the EP10 and EP20, Japan's first fully electronic pianos. These proved to be sturdy and reliable, but in common with other electronic pianos of the 1970s, they sounded truly horrid. They were no competition for the Fender Rhodes and Wurlitzer pianos that dominated the era so, despite their places in history, they are probably best forgotten. However, you wouldn't want to forget the other four products launched in 1973...

Kakehashi had originally designed the RE100 as a machine to reproduce long announcements, but he became aware that — while they were prone to poor performance — tape-echo units such as the Echorec and the Echoplex were becoming popular with musicians. His announcement machine was quickly modified, and the RE100 and RE200 tape-echo units became the precursors of the landmark 'Space Echo' products that were soon to appear.

The Roland SH3. Any resemblance to the Ace Tone SH3 is purely coincidental... or is it?

The Roland SH3. Any resemblance to the Ace Tone SH3 is purely coincidental... or is it?

Then there was Japan's first synthesizer, the SH1000 (see the box above) and its more powerful sibling, the SH3, which appeared as both the Roland SH3 and the Ace Tone SH3, and remains highly sought-after to this day. An instrument of the 'synth-in-its-own-flightcase' school of design, the SH3 shared the SH1000's ability to mix waveforms, offering sawtooth, pulse and square waves, freely mixable in any proportions at each of the 32', 16', 8' 4' and 2' footages. But unlike the SH1000, it offered user-programmable 'Chorus' (which was pulse-width modulation — or PWM — of all three waves at the 8' setting) and there was a pink/white-noise generator that you could direct to either the VCF or VCA control inputs. The SH3 sported two conventional LFOs (the PWM had its own, dedicated rate control) with a neat routing system for pitch modulation, filter modulation, and tremolo. What's more, there was a sample-and-hold section, portamento, a self-oscillating filter, a full ADSR contour generator, and two preset envelope shapes — one brassy, one percussive — for the VCF and VCA.

As you might imagine, the SH3 was remarkably adept at producing interesting noises so, although it could never attain the bite or depth of multi-oscillator synths such as the Minimoog and ARP Odyssey, it became the earliest Japanese example of a 'classic' synthesizer. But this is not quite the impressive accolade that it might seem... After all, the SH3 was only the third synth manufactured in Japan, the Roland SH1000 and Korg 700 being the others!

Milestone: Roland Space Echoes

Before the advent of the Space Echo, the range of effects available was very limited. Distortion, wah-wah and phasing existed, but chorus and ensemble effects were still in the future, as were the complex delay, modulation and spectral effects that we now take for granted. So when Roland released an affordable tape echo with three input channels, a three-spring reverb, 12 reverb/echo modes, and independent EQ of the affected sound, it's no surprise that it was a success.

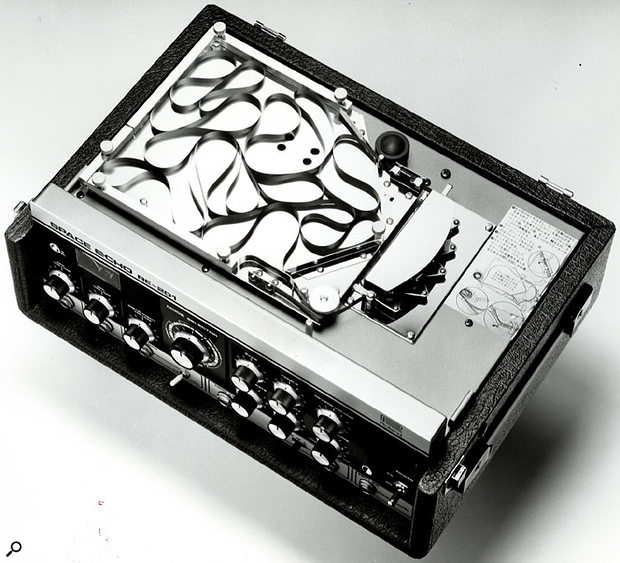

The heart of an echo — an RE201 seen from above with the cover removed, revealing the tape and associated control circuitry.

The heart of an echo — an RE201 seen from above with the cover removed, revealing the tape and associated control circuitry.

OK, the RE201 was not the first Space Echo, having been preceded by the RE100 and RE200, but both of these seem to have disappeared without trace. It was also launched alongside the RE101, but this lacked six of the modes, the EQ and the all-important reverb, so it was the RE201 that became the Space Echo. That it looked superb, and was as rugged as a Chieftain tank were added bonuses that ensured that the RE201 became de rigueur on the road as well as in the studio.

Later Space Echoes offered extra controllability and a modified range of effects. The RE301 added chorus and a sound-on-sound head, while the RE501 and the rackmount SRE555 added chorus, sound-on-sound, a fourth echo head and a balanced (XLR) input. There was even a cut-down model, the RE150, but this stepped all the way back to the RE101 specification (ie. no reverb and no EQ) and even lost one of the three playback heads. But it was the RE201 that embodied the perfect combination of price, facilities, and performance. It was a classic and, amazingly, it remained a current product until 1990. A digital version, the RE3, was launched in 1988, and, although it was a good unit in its own right, it was not a great success.

But when, and where, does the Ace Tone EC1 fit into this story? In many ways, it's a dead ringer for the RE101, with the same three-channel input configuration and prominent VU meter. Sure, the Ace's controls are different, with buttons rather than the rotary knobs of the Space Echoes, but the family resemblance is unmistakable...

1974 MAJOR PRODUCT LAUNCHES

BOSS PRODUCTS

- B100 preamp.

EFFECTS

- AP5 Phase 5.

- RE101 Space Echo.

- RE201 Space Echo.

PIANOS

- EP30 touch-sensitive electronic piano.

SYNTHS & HI-TECH

- SH2000 preset monosynth.

- SH3A monosynth.

1974

Not everything was plain sailing, and it appears that Kakehashi infringed one of Bob Moog's filter patents when he designed the SH3. So a new version appeared in 1974. Externally, the SH3A was almost identical to the SH3, but it sported a new VCF and VCA, and it was this model that Vangelis and a handful of other famous keyboard players adopted in the mid-1970s.

Alongside the SH3A, Roland released the SH2000, a pressure-sensitive preset synth designed to compete directly with the ARP Pro Soloist. This offered a number of facilities that made it more flexible than other single-oscillator synths of the era. For example, the VCO waveform passed through an octave-divider, enabling players to build complex voices using a mix of octave footages from 32' to 2'. Four families of waveform were available — sawtooth, five widths of pulse (including square), PWM, and noise — although only one could be used at a time. There were two LFOs (one with delay), three levels of filter tracking, a fixed filter that could be overdriven, a fully variable 12dB-per-octave resonant filter, and two independent envelope generators. While you could access all of these facilities more flexibly on the SH3A, the SH2000 was the more expressive, thanks to its five parameters of aftertouch sensitivity.

Like the SH3, early SH2000s seem also to have infringed a patent, so a revised version with a new filter (serial numbers 578050 onwards) appeared somewhat later. A second revision (serial numbers 608900 onwards) featured an updated power supply. But whichever version was used, the SH2000 sounded good, and it eventually became widely used in mainstream rock and pop. That's not bad for something designed to sit on top of a domestic organ. Furthermore, like the SH1000 and SH3A, the SH2000 was still available in 1981, nearly a decade after its introduction. Clearly, Kakehashi had got things right first time.

The same year also witnessed the launch of the EP30, the world's first velocity-sensitive electronic piano, but the year was equally notable for the introduction of Roland's first 'classic' effects pedal, the 'Phase 5' (at least one of which — mine — is still in use) and the RE101 Space Echo.

The famous RE201 Space Echo tape-based delay.

The famous RE201 Space Echo tape-based delay.

But all of these were overshadowed by the launch of a product that remains a standard to this day... the Roland RE201 Space Echo (see the box above). A design classic that looks as good now as it did when first unveiled, the RE201 used a much longer tape loop than its predecessors or competitors, reducing wear on the tape, which in turn improved the sound quality and prolonged the useful life of the tape itself. The Space Echo was an instant hit, and remained in the Roland catalogue for the next 16 years. It was also the first Roland product to cross all the boundaries of popular music. A decade before the introduction of affordable digital multi-effects units, its combination of reverb, multi-tapped echo and EQ proved to be equally attractive to guitarists, vocalists and keyboard players, and it soon became impossible to avoid the ubiquitous box, whether on the road or in the studio. Nowadays, tapes for these are becoming harder to find, and owners are prone to forgetting that they need periodic servicing to maintain good performance, but you'll still find numerous RE201s in use.

Nonetheless, it is for another, (ironically) long-forgotten product for which 1974 should be remembered...

A number of Kakehashi's former staff at Ace Electronics had chosen to follow him to his new company, but there was no room for all of them in Roland's company structure, so, on 13th March 1973, Kakehashi established another company, the Music Electronics Group, or MEG Electronics.

MEG's first product was a ceramic 'contact' microphone for an acoustic guitar, sold together with a strange battery-powered preamp. However, just before the product launch, somebody in Japan realised that Meg is a common girl's name in the west, so Kakehashi changed the brand name to something with 'leadership connotations'. I doubt that anybody reading this remembers the product in question, and it would now be of no interest but for one thing: Kakehashi's new brand name was Boss, and when the Boss B100 guitar preamp was released, another legend was born.

Roland's Ensemble Effects

Unlike the chorus effects in the JC amps and the later Boss CE1, Roland's early keyboard ensemble effects used either three or four delay lines (depending upon model) based on a 512-stage BBD (bucket-brigade device) chip called the MN3002. By determining the amount of delay, the modulation rate and depth, and the relative phases between the three signal paths, Roland's designers could have selected between a wide range of delay, reverb, tremolo, vibrato, phasing and chorus effects, all of which can be generated by these chips. However, it seems that they got it just right...

The sound of the Roland ensemble became a distinguishing feature of the company's synthesizers, and although the exact nature of the circuitry changed over the years, the sound remained consistently desirable, and continues to be so nearly three decades later.

1975 MAJOR PRODUCT LAUNCHES

AMPS, MIXERS & SPEAKERS

- JC60 Jazz Chorus guitar amp.

- JC120 Jazz Chorus guitar amp.

- Revo 30 Leslie simulation system.

- Revo 120 Leslie simulation system.

- Revo 250 Leslie simulation system.

EFFECTS

- AF60 "Bee Gee" fuzz box.

- AP2 Phase II.

- AP7 Jet Phaser.

RHYTHM MACHINES

- TR66 Rhythm Arranger.

SYNTHS & HI-TECH

- RS101 string ensemble.

- SH5 monosynth.

1975

The following year saw Roland push further into all manner of music markets, and marked the company's first appearance at the Frankfurt Musikmesse. Many of the new products shown were destined to be significant, although it was not always obvious at the time.

Take the JC120 Jazz Chorus guitar amplifier... This was the first amp to include dual amplifiers and a chorus effect, but I doubt anybody realised in 1975 that this was to become one of the most popular amplifiers of all time. Yet a classic it quickly became, and spawned a dynasty of 'JC' amplifiers that are still in production today.

The sadly under-appreciated RS101 ensemble keyboard. It might have been a leap forward for keyboard-based string sounds, but the mid-'70s synth-buying market didn't notice.

The sadly under-appreciated RS101 ensemble keyboard. It might have been a leap forward for keyboard-based string sounds, but the mid-'70s synth-buying market didn't notice.

And what of the RS101 'Strings'? This was a nice ensemble keyboard that failed to cause much of a ripple upon its release. It offered independent Strings I, Strings II, and Brass presets either side of a keyboard split. Each side of the split offered a Tone control, and independent Slow Attack, variable Sustain and Volume Soft options, thus allowing you to play bi-timbrally. There was also vibrato but, more importantly, the RS101 marked the first appearance of what was soon become to Roland's trademark: its Ensemble effect. Furthermore, the RS101 offered individual VCAs and envelopes for each note, so it could articulate sounds correctly. This was a huge improvement over the market leader, the ARP/Eminent Solina. Physically, it was compact and sturdy, and much lighter than the Solina, so it was also the more convenient of the two. Yet it sank almost without trace. Nearly 30 years later, I still don't understand why this happened, and I suspect that its designers felt the same way.

Similarly, the SH5 was a splendid synthesizer, packed with innovative features, and another of Roland's early synths that was destined — long after its demise — to become a sought-after classic. But at the time, its 'Japanese' sound proved to be more of a disincentive than the appeal of its dual oscillators, PWM, sync, ring modulator, multi-mode low-pass/band-pass/high-pass filter, second band-pass filter, multiple routing, dual envelopes and extensive CVs and Gates. That it sold in moderate quantities has added to its collectability, and the fact that it is undoubtedly the prettiest of Roland's early synths only helps in this regard.

Next, there were the effects units. Foremost among these were a couple of superb phasers: the AP2 Phase II, and its more advanced sibling, the AP7 Jet Phaser, which offered four 'Jet' modes alongside two conventional phasing modes. These were complemented by another fuzz box, the AF60 Bee Gee.

Finally, there were three 'Revo' systems designed to imitate the sound of a Leslie rotary speaker system. The smallest of these, the Revo 30, appeared to be little more than a stereo amplifier with a built-in chorus unit, but you could use this with a standard line-level input or, as with many Leslie conversions on vintage Hammonds, by tapping the amplified signal within the organ itself. Each Revo 30 came with a pair of lightweight, bookshelf 'Revo 30S' speakers, and even these were novel, having a baffle that bounced the sound projected by their cones, damping the high-frequency response, and generating a more organ-like timbre.

Designed for the home rather than studio or stage, the Revo 30 was perhaps the company's earliest attempt to create a 'spatial' effect... which was something that was later to become a major area of its research and product development. But if this was an odd product, the larger Revo units were stranger still. In an attempt to imitate the rotating speaker effect using a single, heavily amplified cabinet, these incorporated a semi-circular array of high-frequency speakers similar to some of Don Leslie's earliest experiments, and the internal electronics panned the signal from across these, thus creating an effect similar to that of a Leslie cabinet but with no moving parts. Lacking the subtlety of the Doppler and amplitude-modulation effects produced by the Leslie, the imitation was not great, but was nevertheless an interesting effect in its own right.

Milestone: The Boss CE1

Although the Boss B100 predated it, the CE1 was the first Boss effects unit, and therefore occupies a unique place in history.

The effects circuitry was based on a single modulated BBD delay line and was lifted in its entirety from the previous year's JC (Jazz Chorus) guitar amplifiers, which had been almost instant successes. But the price of the CE1 was high — many times that of existing effects such as fuzz, wah and phaser pedals — and at first it sold slowly. Very slowly. Furthermore, whereas the JC amplifiers were stereo, and boasted a lush, spatial sound, many people ignored the all-important right output on the rear of the CE1, using it as a mono effect, and thus seriously compromising its performance.

The turning point came in the late 1970s, when prog-rock keyboard players and jazz-rock (or 'fusion') guitarists started to use stereo amplification on stage. Suddenly, the chorus effect came into its own, and, within weeks, the mountain of unsold units had started to shrink. By the time Tony Banks of Genesis had decided to use a CE1 in preference to a Leslie cabinet, Boss were already well on the way to selling their one millionth effects unit.

1976 MAJOR PRODUCT LAUNCHES

AMPS, MIXERS & SPEAKERS

JC160 Jazz Chorus (160W).

BOSS PRODUCTS

- CE1 Chorus Ensemble.

EFFECTS

- DC50 Digital Chorus.

SYNTHS & HI-TECH

- RS202 String Ensemble.

- System 100 semi-modular synth.

- System 700 modular synth.

1976

From the moment he had formed Roland Corporation, Ikutaro Kakehashi had been looking to the future, establishing with his dealers and distributors relationships that he might later be able to convert into 50/50 joint ventures. This bore fruit when he and Geoffrey Brash, Roland's Australian distributor, agreed to form Roland Corporation Australia, launching the company with a party at the Sydney Opera House on 2 April 1976.

The RS202 string ensemble made good on the failure of the RS101, using Roland's rich chorus to fine effect.

The RS202 string ensemble made good on the failure of the RS101, using Roland's rich chorus to fine effect.

That year's new products didn't disappoint either. The RS101 had been commercially overlooked, but its successor, the RS202 String Ensemble was a landmark, introducing the Ensemble Off/I/II switch that was to become Roland's trademark for the next decade. Indeed, the Ensemble defined the 'Roland sound', with the 'II' setting introducing a rich chorus, whereas 'I' produced the faster, deeper ensemble effect that remains widely used to this day. The 103 Mixer, part of Roland's System 100 semi-modular synthesis setup.

The 103 Mixer, part of Roland's System 100 semi-modular synthesis setup.

The RS202 proved adept at producing subtle timbres with a character all their own. Easily distinguished from other manufacturers' ensemble keyboards, it had a transparent quality that sat beautifully in a mix, complementing other instruments, yet never proving uninteresting. Nevertheless, it faced strong competition from the Solina, as well as numerous ensemble keyboards hailing from Castelfidardo in Italy. Many of these sold under well-known Italian brand names — the Logan String Melody, the Elka Rhapsody 490, and so on — but many would later appear with German and even American names, such as the Hohner String Performer, the Wersi String Orchestra, and the ARP Quartet. However, there was soon to be another Italian manufacturer producing 'string synths'. Established in 1976, SIEL would eventually produce a large range of instruments — some under their own name, some rebadged for manufacturers such as Sequential Circuits. Many of these, such as the SIEL Orchestra, would compete directly with Roland's products. It's impossible that Kakehashi could have known the role that SIEL would eventually play in the development of Roland, but the company became highly significant a decade later, as we'll see in a later part of this history.

Another Roland monosynth that would become sought-after long after production ceased, the System 100 comprised five semi-modular products; the 101 Synthesizer, the 102 Expander, the 103 Mixer (which incorporated a simple reverb), the 104 Sequencer (two channels of 12 steps each), and the 109 Monitor Speakers. These fitted neatly together to produce a system that, in retrospect, was rather more interesting than it seemed at the time. Apparently, there was even a stand for the complete system, and rumours suggest that Roland planned to expand the range further, although this never happened.

Roland's truly modular synth, 1976's System 700. The one here, shown in a picture taken in 1998, was a complete system owned by the boss of independent UK record label Mute, Daniel Miller. It was used extensively on the first three Depeche Mode albums.

Roland's truly modular synth, 1976's System 700. The one here, shown in a picture taken in 1998, was a complete system owned by the boss of independent UK record label Mute, Daniel Miller. It was used extensively on the first three Depeche Mode albums.

What there was, however, was the System 700. This huge modular beast marked Japan's entry into the synthesiser market of the, umm... 1960s. Costing in excess of £10,000 (a figure that it still commands today) this was the instrument that placed Roland among the 'big boys' and, although relatively few systems were sold, its user-list started to take on the form to which the company would soon become accustomed.

A complete System 700 comprised six cabinets arranged in two levels of three, plus a five-octave duophonic keyboard. It included nine oscillators, a selection of four voltage-controlled 12dB-per-octave and 24dB-per-octave filters, five voltage-controlled amplifiers, four envelope generators, three LFOs, a mixer, a sequencer, a reverb unit, a delay and a phaser. Fortunately, you didn't need to invest in the complete System in one go. The main cabinet was usually configured as a stand-alone three-oscillator synthesizer, and the other five cabinets added the extra VCOs and LFO (lower left), extra VCFs and VCA (lower right), pitch-to-voltage interface and mixer (upper left), effects (upper right), and the huge three-channel, 12-step sequencer that dominated the centre of the upper row. Apparently, Roland were happy to provide alternative selections of modules, but on the rare occasions that you see System 700s today, they seem to conform to the standard configuration.

Yet, despite the size and stature of the System 700, the most significant Roland of 1976 measured just a few inches across, sat on the floor, and wasn't even a Roland. It was the Boss CE1 Chorus Ensemble, an effects pedal that would spawn the most successful product dynasty the music industry would ever see (see the box above). This was accompanied by the Roland DC50 Digital Chorus, a chunky table-top unit that owed much of its design to the Space Echoes, but which was not a digital processor at all; it was a BBD delay line and chorus effect! Almost unknown today, the DC50 was not a great success.

Milestone: The GS500/GR500 Guitar Synth

The GS500 and GR500 were a remarkable achievement. Not that Roland built every component, of course...

The GS500 was a heavily modified Ibanez guitar, with a single humbucker plus a hexaphonic pickup for driving the GR500, individual on/off switches for each of the four synthesis sections, switches to select the sound of the guitar itself, the synthesizer, or both simultaneously, plus EQ. All this appeared as a beautifully crafted, but very heavy instrument whose body contained magnets that fed the audio output back to the strings, thus creating an 'infinite sustain' system. The GS500 really was far more than just a guitar plugged into a sound generator!

The GS500 modified Ibanez guitar used to control the GR500, and the unique multicore cable and connector that linked them together.

The GS500 modified Ibanez guitar used to control the GR500, and the unique multicore cable and connector that linked them together.

If the GS500 had a limitation, it was that you could only connect it to the outside world using a heavy, multi-core cable unique to the GS/GR500 combination (shown in the above picture). Without this, you owned nothing more than a large, heavy paperweight. Given that there are now no spares left, you cannot even build a new one, and the similar-looking cable used for future Roland guitar synths was wired differently and does not work correctly. While players were to find this very frustrating, it had a huge benefit for Kakehashi and Roland when the prototype was stolen — and then returned as 'unusable' — just hours before its world launch in Australia.

The GR500 synthesizer module (shown below) was amazing, with five sound generation sections — G, P, B, M and S — that you could play individually or in any combination. These were the straight-through Guitar, Poly-ensemble, Bass, Melody, and an 'external Synthesizer' section designed to interface with and control an SH5, System 100 or System 700. The Poly-ensemble, which treated the independent outputs from the 'hex' pickup, was interesting, and produced what would later become Roland's signature 'bowed guitar' sound, but it was the Melody section that captured players' imagination because it was here that the real synthesis took place.

The GR500 sound-generating unit for the GS500 guitar-synth system.

The GR500 sound-generating unit for the GS500 guitar-synth system.

Sounds were generated by a conventional VCO/VCF/VCA architecture reminiscent of the earliest SH-series synths, but with a number of very important bonuses. For example, the VCA was 'touch sensitive', and the output from the Poly-ensemble was an input in the solo synth's mixer, so you could inject the polyphonic sound into the VCF/VCA signal path. Another superb innovation was the output buss system that allowed you to direct the sounds generated by each of the sections to any one of three outputs as well as a global 'Mix' output. In addition, the PC50 Preset Controller was a floor unit that allowed you to set up three mixes for the P, B, M and S sections and select between them using stomp switches. A fourth switch returned control to the guitar. I have never seen mention of the PC50 in any of Roland's documentation — the only reason I know of its existence is because I own one!

1977 MAJOR PRODUCT LAUNCHES

AMPS, MIXERS & SPEAKERS

- GA-series 20, 30, 40, 60, 120W guitar amps.

- GB-series 30, 50W bass amps.

- JC60A and JC120A Jazz Chorus amps.

- SB-series 100 bass amp.

BOSS PRODUCTS

- BF1 flanger.

- GE10 graphic EQ.

- OD1 overdrive.

- PH1 phaser.

- SP1 spectrum.

EFFECTS

- DC10 analogue echo.

- RE301 chorus echo.

GUITAR SYNTHS

- GR500 & GS500 guitar-synth system.

PIANOS

- MP700.

- MPA100 amplifier for MP700.

ORGANS

- VK6.

- VK9.

SEQUENCERS

- MC8 Micro Composer.

1977

By the beginning of 1977, Roland's annual turnover had reached nearly US$30 million, which was approximately one hundred times its 1972 turnover. This made the Roland Corporation almost as large as Ace Electronics had been at the height of their success, but introduced problems of its own, with Kakehashi and his management team seriously overworked, and lacking adequate time to control growth and direction. Kakehashi decided that, rather than impose limits on Roland's activities, he would bring in the extra people that he needed, including senior administrators, a financial controller and — most radically — a Head of Research and Development. In principle, this meant that a greater diversity of ideas and products would start to make their way to the market. In addition to these changes, Kakehashi continued with his plan to form a Group of related companies, with each specialising in a given area of music technology. Although these boundaries have blurred over time, the idea was sound, and on 20th April 1977, he founded Roland ED. Not visible to end-users for many years, the 'ED' name was later associated with some of the Corporation's most revolutionary products.

But long before these changes would have a visible effect on the product range, Roland were already expanding into new areas, and in 1977 they launched a string of products that would have profound repercussions on the whole music industry.

The first of these was the MP700, a 75-note electronic piano in a domestic-style cabinet, which incorporated the first weighted keyboard action on an electronic instrument. Weighing in at 65kg, this was made even less portable by its optional MPA100 amplifier, which produced 120W through four 10-inch speakers. Unfortunately, the sound of the MP700 never justified its size, weight or cost. Lacking touch sensitivity, and with just two analogue piano sounds, a weedy harpsichord and two bass settings on the lowest two octaves, it made no impact on the sales of the electro-mechanical Rhodes, Hohner and Wurlitzer pianos that dominated popular music. However, it was hugely significant because it was the ancestor of the Roland Digital Pianos that would — in 1986 — create and then come to dominate the then-non-existent market for domestic, electronic pianos.

Alongside the MP700, Roland released a pair of electronic organs. Until recently, it was not widely known that, in 1971, Hammond had offered to transfer the manufacture and distribution of the B3 and its siblings to Ace Electronics in Japan, but that Kakehashi had turned down the offer due to rising costs and dwindling sales. But with the launch of the Roland VK9 and VK6, it was clear that he felt that the market for a Hammond-style organ still existed.

The VK9 was the flagship of the pair, and was modelled on Hammond's B3. With a pair of five-octave keyboards, four sets of drawbars that you could access from either manual, electronic chorus/vibrato effects, percussion, a 25-note pedalboard, an optional stand and an optional bench, it also offered a number of innovations such as a 62/5" drawbar in the first group, and a 'Bright' 8' drawbar for the pedals. There was even a converter kit that allowed you to connect it to a Leslie speaker or a Roland Revo.

The VK6 was the Spinet version, with dual 49-note keyboards and two sets of drawbars, no 62/5" drawbar, no stand, and a 13-note pedalboard. However, it offered the Leslie and Revo sockets as standard and, surprisingly, CV and Gate outputs which meant that you could play a suitably equipped monosynth without taking your hands from the organ itself. This feature alone should have ensured some success but, since there seem to be no VK6s in circulation today, it appears that — like the VK9 — it was, at best, a limited success. So maybe the big news lay elsewhere...

Roland's first sequencer, the computerised CV- and Gate-based MC8, which sported a truly staggering 16K of note memory.

Roland's first sequencer, the computerised CV- and Gate-based MC8, which sported a truly staggering 16K of note memory.

Firstly, there was the revolutionary MC8 MicroComposer, the first sequencer with a microprocessor. This let you enter note information using a keypad, and must have looked very modern at the time. But although its heart beat digitally, and the note information was stored in a then-massive 16K of RAM, it spoke to the world in pure analogue, with eight CV and Gate outputs complemented by six pulse outputs for synchronising drum machines, or for using as switching pulses for modular synths.

One of the first of Boss's guitar-effects products to come in pedal form, 1977's OD1 distortion.The maximum sequence length was 5200 notes, which represented a huge step forward from the eight-, 12- and 16-step sequencers of the day. The MC8 even allowed you to allocate multiple pitch CVs to a single Gate channel, thus creating polyphonic parts within the overall sequence. Since it cost around eight thousand dollars, it's not surprising that only 200 were sold worldwide, but, given the huge leap forward that it represented, it's equally unsurprising that many players expressed their awe of it.

One of the first of Boss's guitar-effects products to come in pedal form, 1977's OD1 distortion.The maximum sequence length was 5200 notes, which represented a huge step forward from the eight-, 12- and 16-step sequencers of the day. The MC8 even allowed you to allocate multiple pitch CVs to a single Gate channel, thus creating polyphonic parts within the overall sequence. Since it cost around eight thousand dollars, it's not surprising that only 200 were sold worldwide, but, given the huge leap forward that it represented, it's equally unsurprising that many players expressed their awe of it.

But this was as nothing compared to the raised eyebrows that greeted the GS500 and GR500, the world's first guitar-synthesizer system (see box opposite). Launched just a month before the ARP Avatar, the GS/GR combination was far from perfect but, unlike the ill-fated Avatar, it tracked moderately well and was capable of producing a huge range of sounds previously available only to keyboard players. Perhaps because it required guitarists to develop a specific technique to avoid glitching and tracking errors, the GR500 was of limited commercial success. Nevertheless, there were a handful of famous users, of whom the most prominent was perhaps Steve Hackett, who later went on to become a devotee of Roland's seminal guitar synth, the GR... Ah, but I'm getting ahead of myself. As the ancestor of all Roland's guitar synths, the GS500 and GR500 hold a special place in history.

Oh yes, and let's not forget the Boss products launched in 1977. After a few more experiments with Roland-style effects units such as the BF1 Flanger, this was the year that Boss launched their classic Boss stomp-box format, as shown above in the picture of the OD1 released that year. It's a huge testament to the design that, nearly 30 years later, the same metal chassis, rubber foot, recessed knobs and FET switching are to be found on the huge range of Boss pedals now in production.

Milestone: The CR78 CompuRhythm

The forerunner of all the great Roland drum machines, the CR78.

The forerunner of all the great Roland drum machines, the CR78.

Nobody paid much attention to the CR78 when it first appeared. Kakehashi claims that it was the first musical instrument to contain one of those new-fangled microprocessor thingies but, at first sight, it seemed no more interesting than any of a host of other manufacturers' rhythm boxes. It offered just 14 sounds and four-note polyphony and, while it was nicely designed, its numerous bossanova, samba, mambo, beguine, rhumba and waltz presets did little to dispel the 'home organ' impression. Nevertheless, there were a couple of bits of magic about the CR78. These were 'Program Rhythm' and the WS1 Write Switch, which made the little box the first drum machine that allowed you to devise, store, and replay user-programmed patterns.

For three years, the CR78 remained almost unknown, but in 1981, Phil Collins released 'In The Air Tonight', and the little Roland instantly became an essential part of almost everyone's musical vocabulary. Indeed, its limited capabilities have stood the test of time, and the CR78 is still used on all manner of recordings, primarily in ambient music and other forms of electronica. Many surviving units are now equipped with MIDI retrofits, but the provision of an early 12ppqn (48 counts per measure) external clock input means that you needn't hack the case of your vintage treasure if you don't want to.

The CR78 had a little brother, the CR68. This shared the sounds and rhythms of its (eventually) illustrious sibling, but lacked many of its performance features, and was not programmable.

1978 MAJOR PRODUCT LAUNCHES

AMPS, MIXERS & SPEAKERS

- Cube 40 guitar amplifier (40W).

- GA-series 50 guitar amplifier (50W).

- JC50, JC200 and JC200S Jazz Chorus amps.

- RD125L Revo.

- RD155L Revo.

- SB-series 200 bass amp (200W).

BOSS PRODUCTS

- CS1 Compression Sustainer.

- DB5 driver.

- DM1 Delay Machine.

- DS1 distortion.

- GE6 graphic EQ.

- TW1 wah pedal.

EFFECTS

- DC20 analogue echo.

- DC30 analogue delay.

- GE810 graphic EQ.

- GE820 graphic EQ.

- PH830 stereo phaser.

- RV100 reverb.

- RV800 reverb.

PIANOS

- MP600 Combo piano.

RHYTHM PRODUCTS

- CR68 Human Rhythm Player.

- CR78 CompuRhythm.

SYNTHS & HI-TECH

- JP4 (Jupiter 4) polysynth.

- MRS2 Promars monosynth.

- RS09 Organ/Strings keyboard.

- RS505 Paraphonic Strings.

- SH1 monosynth.

- SH7 monosynth.

- SH09 monosynth.

1978

Throughout the mid-1970s, Roland had supported two distributors in the USA. Multivox had been doing a reasonable job on the East Coast, but had little penetration into the huge and important markets on the West Coast so, in 1976, Kakehashi had appointed a Los Angeles company, Beckman Musical Instruments, to be its West Coast distributor. With both companies working in parallel, it became apparent that Tom Beckman's BMI was the more successful so, in 1978, Roland and BMI formed Roland US, with each owning 50 percent of the new joint venture. Although adverse financial conditions and a fundamental difference of opinion about how to deal with them were later to force Roland to buy Beckman's share and make Roland US the company's first wholly owned subsidiary, the joint-venture strategy was close to Kakehashi's heart, and it seemed like a good move at the time.

The same year also saw the first results from 1976's expansion in the development team, and witnessed an explosion in Roland's product range. There were more amplifiers, more Boss effects units, two new ranges of rackmount and desktop effects units, more synths, another piano, more speaker systems... and some now-classic instruments that included the JP4 'Jupiter 4' Compuphonic polysynth, the SH09 monosynth, and the now-legendary CR78 CompuRhythm (see box earlier).

The first true Roland polysynth, the Jupiter 4.

The first true Roland polysynth, the Jupiter 4.

Released as part of Roland's Compuphonic range (see box below) the Jupiter 4 was the company's first true polysynth, born into a world dominated by the Sequential Circuits Prophet 5, the Oberheim OBX, the Korg PS3000-series and the Yamaha CS80. It's unlikely that Kakehashi and his team had designed the JP4 to compete against any of these because, like the SH1000 and SH2000, it was designed to sit on top of an organ. What's more, with just a single VCO per voice (whereas each of the competitors offered two or, in the case of the PS3300, three) it was always going to be the poor sonic relation. It was also a bit of a loser in the keyboard department: its four octaves compared poorly to the Americans' five. Furthermore, its four-voice maximum polyphony was half the Yamaha's eight, and was dwarfed by the 48-voice polyphony of the Korg PS-series. It also lacked the CS80's velocity- and aftertouch- sensitivity. And with just 10 presets and room for only eight programmed patches, its memory seemed rather meagre, even in 1978. Whichever way you looked at it, the JP4 was a bit of a lightweight.

On the other hand, its secondary facilities put its competitors' to shame. It sported Roland's trademark chorus and three Unison options that made it a powerful monosynth provided, of course, that you didn't want more than one pitch in your sound. And there was an excellent arpeggiator, perhaps used most famously by Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran. But it wasn't only the electro-pop bands of the early 1980s that eventually adopted the Jupiter 4, and a list of its fans now reads like a 'who's who?' of the era.

The JP4 had one more trick up its sleeve... its price. At just £1800, it was much cheaper than its competitors, and appealed greatly to those for whom Prophet 5s and OBXs were simply unaffordable.

The Compuphonic partner to the Jupiter 4, the MRS2 Promars.

The Compuphonic partner to the Jupiter 4, the MRS2 Promars.

If the reputation of the Jupiter 4 has improved over the years, that of its Compuphonic partner, the MRS2 'Promars' monosynth, has not. In part this may be because its two oscillators were not truly independent, or because the slightly squelchy VCF and VCA retained an archetypically Roland — ie. clean and precise — character, and in 1978 most players were still wedded to the fatter sounds of Moogs and ARPs. Nevertheless, with powerful modulation capabilities and performance controls, the Promars was a good instrument, and one that has been unfairly overlooked. The 64-note successor to the MP700, 1978's MP600 electronic combo piano.

The 64-note successor to the MP700, 1978's MP600 electronic combo piano.

Roland released seven other keyboards in 1978. Of these, we can safely ignore the MP600 piano shown above, a 64-note successor to the MP700. The RS09 Organ/Strings, which combined a very basic organ sound with a limited string ensemble section, was only slightly more interesting.

Better was the RS505 Paraphonic Strings, which replaced the RS202, and combined strings, a basic polysynth section, and a bass section. Very similar to the ARP Omni released three years earlier, the RS505 was hobbled by the use of a single filter and filter envelope for the entire instrument, rather than one for each note. However, in true Roland style, there was an unexpected bonus: an audio input that allowed you to pass external audio through its glorious quadruple-BBD ensemble effect.

One of Roland's finest string synths, the paraphonic RS505.

One of Roland's finest string synths, the paraphonic RS505.

And what of Roland's monosynths? The SH1 was a surprisingly useable single-oscillator instrument that later became popular with synth-pop bands such as Depeche Mode and Erasure. In contrast, the unwieldy SH7 was the most complex integrated monosynth ever produced by the company. It offered duophony and plenty of synthesis features, but it was a turkey. For some reason, it sounded thin and uninspiring, and few players were beguiled by its size or promise.

But then there was the SH09, which, despite being the cheapest, lightest and ostensibly least powerful of the three, was to become another minor classic with yet another 'who's who?' of fans and users. Like the SH1, this offered just a single oscillator, with sample & hold, delayed vibrato, a self-oscillating filter and an external signal input with an envelope follower... all of which were nice. But to concentrate on the feature-count was to miss the point: the SH09 was one of those rare instruments in which the whole was somehow greater than the sum of the parts.

The Compuphonic System

Until the development of the Compuphonic system, the controls of all Roland's synthesizers formed part of the synth circuits themselves. In contrast, those of the microprocessor-controlled JP4 and Promars reported their position to a computer. This computer then determined the voltages that controlled the VCOs, VCFs and VCAs. You might surmise, therefore, that there is at least one A-D and one D-A converter in each model, and that all the controls would exhibit audible stepping of parameters. And you would be right. Like all analogue synths with memories, the Jupiter 4 and Promars were hybrids of analogue signal paths and digital control.

The processor used was a primitive eight-bit device called the Intel 8048. Roland multiplexed the data from the knobs, sliders and switches so that the fully variable controls utilised six bits each, and the switches utilised the other two. This meant that there were just 64 possible positions for each knob or slider. The limited resolution exacerbated parameter quantisation problems, but speeded data handling and reduced the memory requirement of the whole synth to just 128 words of RAM.

Epilogue

By the start of 1979, Roland had become one of the primary names in rock & roll instrument manufacture. Guitarists loved the Jazz Chorus amplifiers, and Boss effects were already digging deeply into markets previously dominated by Electro-Harmonix and MXR. Similarly, the Space Echoes had become de facto standards. Then there were the GS500/GR500 guitar synth, the CR78 rhythm machine, the MC8 MicroComposer, and the huge System 700 modular synth. Sure, the market for conventional monosynths was still dominated by Moog and ARP, while Sequential Circuits and Oberheim seemed to have the polysynth market neatly sewn up. But it seemed that nothing could stop the progress of Kakehashi and his team, and for another couple of years this would prove to be the case.

But even in 1978 the signs were there... a crisis was looming, one that would nearly put Roland out of business. As we know, the company survived, but there were some serious difficulties to be overcome... which is where we will pick up this story in Part 2.

Thanks to the Audio Playground Keyboard Museum, Florida (www.keyboardmuseum.com), Roland US and Roland UK for help with sourcing many of the pictures for this article.