After 17 years mixing almost everything that came out of Jam & Lewis's Flyte Tyme Studios, there's very little Steve Hodge doesn't know about making R&B records work.

Steve Hodge bridles a bit when I say that people don't know who he is, though he's quick to acknowledge that he has worked to stay out of the spotlight as hard as some other engineers have laboured to get in it. But while avoiding its glare, he has still managed to cast a lengthy shadow. As virtually the sole mixer for the Grammy-winning production team of Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis from 1986 to 2003 and the chief engineer at the duo's Flyte Tyme Studios, Hodge crafted the final versions of hit records for artists including Janet Jackson (including Control and Rhythm Nation), George Michael (Faith), Mariah Carey, Michael Jackson (HIStory), Natalie Cole, the Spice Girls, Toni Braxton, Usher and TLC, as well as records for Sting, Rod Stewart and the Human League.

Hodge's career might be summed up in one of the few photos in which he's seen with the recording artists he's worked with (below, right), where a very young, long-haired Hodge is standing at the edge of the scene, almost protective of the MCI 16-track deck (an early model, with the electronics on top) next to him. Meanwhile, Don Costa, the great musical arranger, and MGM Records' chief studio engineer Val Valentin — also Hodge's uncle — laugh it up with Sammy Davis Jr as the Rat Packer finishes his biggest hit 'The Candy Man', in 1969. "In the early 1980s, before automation, you always had a Polaroid camera on the SSL to take snapshots of the console so you could recall the settings," says Hodge. "As a result, there were lots of other kinds of pictures taken during sessions, but I used to really try to keep myself out of them!"

At MGM's studios; at Studio In The Country in Louisiana, where Hodge worked in the '70s on records for New Orleans figures like Professor Longhair, Zydeco legend Clifton Chenier, bluesman Clarence 'Gatemouth' Brown and the famous Wild Magnolias; and finally at Jam & Lewis's Flyte Tyme Studios, he usually managed to be in the right place at the right time.

Steve Hodge at the desk in the Institute of Production & Recording in Minneapolis, where he now teaches.Photo: Dave Rideau

Steve Hodge at the desk in the Institute of Production & Recording in Minneapolis, where he now teaches.Photo: Dave Rideau

Jammed Together

Hodge was part of a revolution in record production and mixing: digital technology was making records denser and more complex, with many more elements. Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis were combining techniques like sampling with hands-on musicianship. Hodge was figuring out how to put it all together.

"Most of Jimmy's and Terry's records — most records since then, really — are a combination of a solid, dense bottom over which a melodic top rides," he explains. "With Jimmy playing a very dense, funky bass line and a vocalist like Janet Jackson singing a very airy-voiced melody on top of that, the contrast was spectacular. That sound came to characterise the next generation of R&B records, and that's what you're aiming for in a mix — contrast that creates a narrative, that builds a creative tension."

Getting a coherent low end is one of the biggest challenges on a mix. The term that often comes up in this context is the ubiquitous but vague 'tight'. Hodge has a roadmap for that. "Listen to the kick and the bass together and adjust the equalisation on the kick drum so that you create a 'hole' for the bass to fit in," he explains. "I usually cut the EQ around 400Hz just a bit — a couple of dBs so that it doesn't begin to sound hollow — and see how the bass then fits against the kick. It's usually a perfect fit: the bass and the kick make a very coherent low end with lots of punch that occupies its own space in the track and leaves lots of room for everything else."

A youthful Steve Hodge (left).Photo: Dave RideauAnother component of building a good bottom is to compare the pitches of the kick and the bass. "The kick has its own pitch just as the bass instrument does," Hodge stresses. "This becomes more pronounced with drum machines. I remember that from the days of the famous Roland 808 kick, which had a real apparent and pitched ring to it. Get the bass and the kick into the same pitch range and that will solve a lot of subsonic issues."

A youthful Steve Hodge (left).Photo: Dave RideauAnother component of building a good bottom is to compare the pitches of the kick and the bass. "The kick has its own pitch just as the bass instrument does," Hodge stresses. "This becomes more pronounced with drum machines. I remember that from the days of the famous Roland 808 kick, which had a real apparent and pitched ring to it. Get the bass and the kick into the same pitch range and that will solve a lot of subsonic issues."

For the other end of the contrast he seeks between the bottom and the melodic elements, Hodge also relies on EQ. "Especially on a female voice, adding at 15kHz really brings an 'airiness' to the vocal and makes it ride nicely on the top of the track," he says. "The problem that could cause is additional sibilance; today, we can automate that out on Pro Tools. I routinely de-ess with automation now by ducking the level of the 'esses' down without affecting the rest of the word. It can be that precise.

"You might also find you need to warm the vocal up a bit when you do that, which you can do by adding a little bit of low mid-range and some good analogue compression. A vocal chain that I like that can accomplish this is an AKG C12 through a Great River MP Series mic pre, a Great River EQ 2NV equaliser and Dbx 160SL 'Blueface' comp/limiter."

Also A Tracker

Steve Hodge would become best known for mixing, but he prides himself on his tracking abilities. He learned from the best in the '70s, he says, including his uncle Val and engineers and producers like Mike Curb, Bruce Swedien, Malcolm Cecil and John Boylan, who he assisted in the mixing of Boston's stunning debut album in 1976.

In 1974, Hodge tracked the debut album for the Wild Magnolias, the quintessential New Orleans street band and still required listening amongst musicologists. With as many as 20 musicians in the studio at a time, it was a tracking circus. "The sessions really took advantage of the Westlake rooms design that I had grown up with at MGM," he recalls. That included the piano trap built into one wall; modelled after the drum trap at MGM, it swallowed two-thirds of the grand piano but with enough headroom for Hodge to set a pair of Neumann KM86 condenser microphones up in an X-Y configuration. There were also smaller built-in traps for guitar and bass amps, miked with a Shure SM57 and an EV RE20, respectively, all set to cardioid polar patterns.

During the '70s Hodge was resident at Studio In The Country, Bogalusa, Lousiana, where he recorded many classic Southern records.Photo: Dave RideauBut that was about as much isolation as he could conjure up. The drum kit was in the middle of the room with an AKG D12 on the kick, a 57 on the snare, a KM84 on the hat and a single AKG C24 for an overhead. Percussion was similarly naked, confined to one Neumann U87. In front of the control room window, Hodge set up a pair of C24s in an M+S pattern as the main recording setup for the group's changing array of vocalists and street percussionists. All of this was sent through an Auditronics desk and the studio's 24-track 3M 79 multitrack running at 30ips.

During the '70s Hodge was resident at Studio In The Country, Bogalusa, Lousiana, where he recorded many classic Southern records.Photo: Dave RideauBut that was about as much isolation as he could conjure up. The drum kit was in the middle of the room with an AKG D12 on the kick, a 57 on the snare, a KM84 on the hat and a single AKG C24 for an overhead. Percussion was similarly naked, confined to one Neumann U87. In front of the control room window, Hodge set up a pair of C24s in an M+S pattern as the main recording setup for the group's changing array of vocalists and street percussionists. All of this was sent through an Auditronics desk and the studio's 24-track 3M 79 multitrack running at 30ips.

Yet it sounded good enough to achieve legendary status, thanks mainly to the Westlake room's inherent deadness. "It was super-dead," says Hodge. "What ambience there is comes from the fact that there were so many open microphones. The walls were very non-reflective and that meant no standing waves or bass node build-up. The sound is incredibly tight and punchy. So much so that we used that same way of recording with Lou Rawls when he demanded that he be able to sing the 'keeper' lead vocals in the same room with and at the same time as the band. We set up a C12 for him and let him rip and you'd never know there was no isolation between him and the band."

Hodge enjoys reminiscing about his tracking days and credits them with his success as a mixer. Talking about his work on the next Soul Asylum LP, The Silver Lining, which he tracked and which was his first major project since splitting with Jam & Lewis several years ago, Hodge muses: "The idea of someone else mixing a record you've done from the beginning took some getting used to, since when I came up through the ranks was a time when the same engineer would track, overdub and mix a project. But in those days, you basically were mixing as you went along, bouncing between tracks. And when you think about it, especially as records became more complex, it really helped to have a new set of ears on it that could bring in another perspective. The band brought Chuck Zwicky in to mix this record, and I'm fine with that. Chuck is a 'neutral' party; that is, he doesn't have the same emotional attachment to how the tracks were accomplished. It's a subliminal thing but very real: you know what the notes are — they don't have to be loud for your brain to pick them out. But that's not how everyone else hears the record. Another set of ears is what brings those elements out where they need to be. When you think about it, pop records have always been the work of a committee, even though only the artist's name is on them. I think that illusion is part of their charm."

Vocals

Steve Hodge has always had a thing for large-diaphragm microphones — his long-time favourite is the AKG C12 — but he has his twist on them. "Engineers end tend to use cardioid patterns to get the up-close effect for vocals, but I use an omni pattern setting," he explains. "It goes back to the fact that I always got to record in great-sounding rooms and I really took advantage of that. I like to let the room into the vocal a bit. If I need more up-close, then I add EQ, boosting it a little around the low mid-range. I don't do that as much any more since the room I work in now most often — Mastermix's studio B [at the Institute of Production & Recording in Minneapolis, where Hodge now teaches] has a small, dry-sounding vocal booth. And lately I've been using a Neumann U67."

A typical Steve Hodge vocal setup using a Neumann U67.Photo: Dave Rideau You might not suspect that from Janet Jackson's records, but Hodge says he could keep the little-girl quality in her vocals by adding extra high end, then attenuating it with an Orban de-esser to minimise the sibilance the high end emphasises, as well as compression on the high end. "Using the open pattern on the mic helps in the same way," he adds. "The thing you have to understand with vocals is that every time you add something to the signal, it has a [knock-on] effect on everything else you have on the sound. It's like a chess game — you always have to consider what will happen three or four moves ahead of when you do it."

A typical Steve Hodge vocal setup using a Neumann U67.Photo: Dave Rideau You might not suspect that from Janet Jackson's records, but Hodge says he could keep the little-girl quality in her vocals by adding extra high end, then attenuating it with an Orban de-esser to minimise the sibilance the high end emphasises, as well as compression on the high end. "Using the open pattern on the mic helps in the same way," he adds. "The thing you have to understand with vocals is that every time you add something to the signal, it has a [knock-on] effect on everything else you have on the sound. It's like a chess game — you always have to consider what will happen three or four moves ahead of when you do it."

Mariah Carey's shyness when singing in the studio led her to record with as much privacy as possible, just her and the engineer, and far away from the rest of the production as possible. When Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis produced albums for her, including Rainbow, Share My World and Glitter, the soundtrack to her famously disastrous film debut, Carey would send the vocals to Minneapolis, recorded on two-inch 24-track tapes, with rough mixes of the tracks. "The problem was, the vocals would have effects and echo pre-mixed onto them," says Hodge, shuddering a bit at the thought. "That was difficult, but we loved Mariah so we put up with it."

Hodge is still in awe of Michael Jackson's studio performances. "HIStory was supposed to be a greatest hits record but Michael recorded so much new material that it ended up being a double album," he says. The connection to Jam and Lewis came out of a duet that they recorded with Michael and Janet, called 'Scream'. "I used the AKG The Tube microphone on him for that," he says. "I ran it into the Avalon 737 preamp with the EQ and compressor built in. With Michael, you set the mic and stand back. He moves around incredibly when singing, just like he does on stage. But he has this remarkable knack for getting back precisely on mic in time for the line. He could circle the room and never miss a line. The problem was that the mic would pick up all of the noises he made — finger-snapping, mouth-popping and so on; he's a huge foot-stomper. A lot of the percussion you hear on his records is actually him. What you have to do is build new percussion tracks around his vocal later. You have to augment it rather than try to cover it up."

Jam & Lewis

In 1975, Hodge went to work for Westlake Audio, which had converted a building on Wilshire Boulevard in West Hollywood into a mix room to demo gear. "The trouble was, people liked the room so much they started booking it out to mix in," Hodge says. It became Westlake Studios, where Hodge further refined his mixing talents. It was there he first met Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, then working in Prince's band and just starting their production careers.

Photo: Dave Rideau

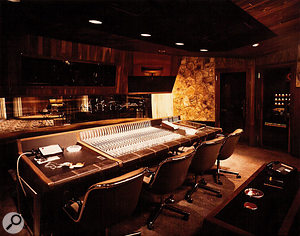

Photo: Dave Rideau Steve Hodge (with back to camera, above) during the construction of Westlake Beverly Studio A in 1976; and below, the finished studio.Photo: Dave RideauThe project that would set the tone for their 16-year collaboration was Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation, the recording of which moved from the small studio on Nicolette Street in Minneapolis where the producer duo started out with a small Harrison MR4 mixer to the new four-room Flyte Tyme with its array of Harrison Series 10 consoles and Westlake-based 'wooden lips'-design main monitors. (Though Hodge steadfastly stuck to Yamaha NS10s for his mixes throughout that time.)

Steve Hodge (with back to camera, above) during the construction of Westlake Beverly Studio A in 1976; and below, the finished studio.Photo: Dave RideauThe project that would set the tone for their 16-year collaboration was Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation, the recording of which moved from the small studio on Nicolette Street in Minneapolis where the producer duo started out with a small Harrison MR4 mixer to the new four-room Flyte Tyme with its array of Harrison Series 10 consoles and Westlake-based 'wooden lips'-design main monitors. (Though Hodge steadfastly stuck to Yamaha NS10s for his mixes throughout that time.)

"The title track is actually based on a guitar loop we pulled from a Sly & The Family Stone record," says Hodge, noting that in the early '90s sampling was still regarded more as an homage to the artists being sampled than an attack upon their intellectual property. Though there was space for it — Hodge was running a pair of Otari MTR100 24-track decks (with Dolby SR at 15ips) — he didn't stripe with SMPTE timecode. Instead, he sampled using an AMS 1580 or Publison box, and then transferred to a Linn drum machine.

Jam and Lewis liked to create beats that they could riff to, adding fills on the fly, in real time as the tape ran, as opposed to using a sequencer. "They even had alternate patterns ready that they would hit a button and have them come up in the song, all on the fly," he says. "The beat was quantised, but the fills and turnarounds weren't, and that makes a huge difference in the feel of the track. We also overdubbed cymbals and other percussion live, just before we mixed."

Drum samples generally resided in the samplers, animated not by timecode but triggered by a trigger track Hodge created by copying the song's back-beat snare track playing only the two and four, and sending it through a digital delay that would echo them to add hits on beats one and three — in essence, creating a quarter-note trigger track.

Mixing Rhythm Nation followed a standard protocol that Hodge had developed over the years. "I usually start with the rhythm section — kick, snare, overheads, bass," he explains. "If the drums are live as opposed to machine, I'll start with the overheads first and then add the close-in microphones. That gives the sound some context."

Winds Of Change

Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis moved to Los Angeles in 2003 and have a smaller studio dubbed Flyte Tyme West there. Hodge says the 9/11 tragedy and its effect on air travel immediately after cut into the number of artists willing to travel beyond LA and New York. Nonetheless, Hodge has elected to stay in Minneapolis, where he has a family and roots now. It's perhaps a kind of geographical anonymity. He says he maintains a good relationship with the producers, but that it was time to move his career in other directions.

"Maybe I should have been more public years ago," he says. "But I'm also very happy doing work on the indie-record level now here. You can be more creative. You can also do a record from start to finish, which is how I started out. I kind of missed that."

The Big Mix

'HIStory', the title track of Michael Jackson's 1995 greatest hits album, was historic in scope. For the mix Hodge was faced with 192 tracks sprawled over four Sony 3348 48-track digital tape decks. With two studios at Larrabee North studios in Los Angeles holding one pair each of the machines, Hodge chose one as the master deck and ran SMPTE timecode to the other three. It took both SSL G-plus consoles to do the mix, which incorporated a full symphony orchestra, two choirs, backing tracks by Boyz 2 Men, scores of Jackson's own vocals and more samples than anyone could keep track of. "The best part, though, is we had to do the mix in one day," Hodge sighs. "Michael never did anything in a small way."