In 2001, Propellerhead’s Reason broke new ground by virtualising every element of the classic analogue synth studio. Six years on, is the original still the best?

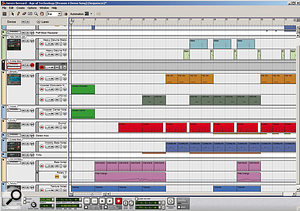

This screen shows nearly everything new that Reason has to offer. Note the individual automation lanes that have been expanded for the ReMix sequencer track. I snapped this at a ridiculous screen resolution to give the sequencer a chance to show off, and to reveal almost all that the Tool Window, right, has to offer.It’s hard to believe, but over two years has passed since the last release of a proper update to Reason, Propellerhead’s ground–breaking virtual electronic studio. Sure, the team have been managing incremental updates to keep up with Apple’s Intel processor–equipped Macs and Bill Gates’ Vista OS, plus the odd bug or two, but there have been no new toys since early 2005.

This screen shows nearly everything new that Reason has to offer. Note the individual automation lanes that have been expanded for the ReMix sequencer track. I snapped this at a ridiculous screen resolution to give the sequencer a chance to show off, and to reveal almost all that the Tool Window, right, has to offer.It’s hard to believe, but over two years has passed since the last release of a proper update to Reason, Propellerhead’s ground–breaking virtual electronic studio. Sure, the team have been managing incremental updates to keep up with Apple’s Intel processor–equipped Macs and Bill Gates’ Vista OS, plus the odd bug or two, but there have been no new toys since early 2005.

Stage–managed peeks at a new monster modular synth device some months back told us that the team haven’t just been taking some extended R&R. The recent start of a user–based beta–testing cycle confirmed a new release’s imminence, and finally Reason 4.0 has gone golden master. It’s on my laptop, and it’s ready to rock.

What’s It All About?

We haven’t space for yet another full overview of Reason — the software has been covered in four SOS reviews before this one, not to mention dozens of ‘how–to’ pieces over the years. Newcomers should check out the ‘Reason In A Nutshell’ box for a crash course in what’s going on, then visit Propellerhead’s informative web site to fill in the gaps, and finally surf SOS’s article archive for some hands–on digging into what the software can do.

Suffice to say that, as it did in v1.0, Reason aims to do in software everything that anyone familiar with mainly analogue electronic music hardware would like to do if they could afford lots of hardware. It’s always been designed by musicians who just happen to be great coders, and represents their (and their users’) idea of what the ideal, flexible electronic music studio should be. It looks familiarly retro but hides a lot of clever ideas about how the desired result should be achieved.

The numerical increment certainly does indicate a significant update to Reason. How significant it’ll be to you, however, will depend on what your expectations were beforehand and how open you are to what Propellerhead produce in response to their own, and their users’, needs. They do listen, but some of you may think they don’t listen hard enough, or to the right requests!

That monster modular may not have been requested per se, but it implements programming features and some synthesis types that certainly are on the collective wants list. But an arpeggiator should, arguably, have appeared much earlier in Reason’s life, and the sequencer does not have the perception of being quite as sophisticated as it could. Both these issues are dealt with — and very effectively — in this upgrade. Groove manipulation was never a strong point, either, but a course of steroids appears to have been taken by the software...

The Mighty Thor

The Mighty Thor: Now you can see what I mean. Oscillator 3 and the global filter have been disabled to show what that looks like.The most noticeable addition to the rack is the new Thor Polysonic modular synth, and this is the device that will be taxing your CPUs as you attempt to tame its power. Propellerhead have done it again: they’ve created a device that you would sorely love to see as a stand–alone plug–in to slot directly into other environments (if not as a real piece of hardware!), but that is hardly a complaint.

The Mighty Thor: Now you can see what I mean. Oscillator 3 and the global filter have been disabled to show what that looks like.The most noticeable addition to the rack is the new Thor Polysonic modular synth, and this is the device that will be taxing your CPUs as you attempt to tame its power. Propellerhead have done it again: they’ve created a device that you would sorely love to see as a stand–alone plug–in to slot directly into other environments (if not as a real piece of hardware!), but that is hardly a complaint.

Fully stretched out, Thor gives the impression of being the biggest device in the Reason rack. This is an illusion: it’s exactly the same size as the NNXT super sampler player. Still, although NNXT might be more conceptually complex, thanks to all those samples with all those individual sets of synth parameters, Thor is a monster, visually. I had to change resolution on my laptop’s screen so that I could see the whole thing without scrolling. This is the synth’s one down side: it’s equipped with RSI–inducing swathes of knobs, sliders and buttons. I can get used to it — the more knobs the better, right? — but highly recommend an external hardware controller to everyone who can afford it. Newcomers may be daunted, but anyone with experience of other synths, soft or hard, will see that layout is logical and sound creation just seconds away.

Thor is a deep synth and could, as you can see from the screen dump, stand its own full review. It reminds me in many ways of Green Oak’s freeware classic Crystal. It is in concept a modular (or more correctly, semi–modular) synth, but that’s ‘modular’ in the modern sense of the word. Each of the synth’s sound–making elements has its own discrete ‘module’ on–screen, ready–linked from the time the synth is loaded into the rack. You need do nothing to start programming save enable the desired modules and tweak away. The links, both audio and control, can, of course, be subverted using both an on–screen modulation routing system and audio and rear-panel gate/CV sockets, allowing the expected integration with other devices.

To save rack space, Thor has three levels of unfolding. It can be extremely minimal, showing just a patch-selection display, or it can have just its controller module showing, which adds a handful of assignable controls and some playback parameters. This display reveals Thor’s maximum polyphony to be 32 voices — a wise move, perhaps, on Propellerhead’s part. Rather unexpectedly, a separate parameter for release polyphony is provided, allowing you to control the number of voices that are allowed to decay normally when new notes are triggered, and thus to control ‘voice stealing’.

With Thor fully expanded, you get an eyeful of the knob–laden main programmer panel. Its main area offers all the synth editing parameters; below that is the compact modulation bus routing section — I’ll call it a matrix from now on — and it’s this that allows you to grab audio or control signals and re–route them. At the bottom of the rack is the step sequencer. This was a bit of a surprise, but one that pleasantly references many true modular synths, which often have such a device as much for automating general control voltages as for controlling oscillator pitch.

Voice Training

The main programmer is divided, via subtle colour–coding, into two sections, Voice and Global. This isn’t as strange as it may seem. Envelope generators and LFOs in the voice section are polyphonic, with each new voice played in a chord, for example, triggering a new cycle, without cutting off any previous cycles.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. To start from the beginning, a Thor voice can have up to three oscillators, two filters, three envelope generators and LFO, with waveshaper, mixer and amplifier thrown in. The output of this section is routed straight through the ‘global’ modules — another filter, LFO and EG, plus tempo–sync’able delay and chorus effects. The LFO and EG are single trigger devices, but the EG has its own sophistication. In the end, though, this fixed audio and control signal path is moot, since the modulation matrix allows you to configure your own connections in your preferred order. A finished Thor ‘patch’ will also include settings for that modulation matrix, and the step sequencer.

Thor’s sockets — lots of ’em. Check out the helpful notes, too.The rear–panel interfacing of the new synth is comprehensive, with audio outs augmented by inputs which can be routed, via the modulation matrix, anywhere in the synth, allowing external audio to be ‘Thor’d’ or ‘insert’ effects to be added anywhere in the synth’s signal path. Gates and CVs are similarly configured — both to play the synth and to move control signals in and out of a given patch.

Thor’s sockets — lots of ’em. Check out the helpful notes, too.The rear–panel interfacing of the new synth is comprehensive, with audio outs augmented by inputs which can be routed, via the modulation matrix, anywhere in the synth, allowing external audio to be ‘Thor’d’ or ‘insert’ effects to be added anywhere in the synth’s signal path. Gates and CVs are similarly configured — both to play the synth and to move control signals in and out of a given patch.

Now let’s back up a bit and add a bit more detail. Each oscillator can choose from no fewer than six oscillator types: analogue, wavetable, FM pair, phase modulation, multi–osc, and noise. Analogue gives you a choice of sawtooth, pulse, triangle and sine waveforms, with PWM on the pulse (or square) wave, plus tuning and keyboard response controls. Shame that PWM wasn’t applied to all waveforms.

The wavetable option offers 32 wavetables, each with up to 64 separate waveforms. The control set remains simple, but complexity abounds. I couldn’t find a list of the wavetables, but there are several derived from PPG instruments, didgeridoo and so on — lots of interesting textures to modulate and sweep through.

The phase modulation option (inspired by Casio CZ synths from the ‘80s, which were themselves tangentially inspired by Yamaha’s then–proprietary FM synthesis) offers an approach many won’t have encountered. Two waveforms are modified to create changing timbres and different filter–like characteristics.

Genuine FM is also present, with the FM pair oscillator. In this, one sine–wave oscillator is a carrier and the other a modulator, and a surprising range of complex sounds can be generated. Don’t be concerned about four– or six–operator synthesis, algorithms, or the range of waveforms available on later synths derived from the Yamaha model: it’s pretty simple here, but powerful for all that.

The Multi Osc is related to the analogue option, with sawtooth, pulse, triangle and sine waveforms, and its big trick is detuning — adding measurable intervals (though with a random option) to the overall sound. It’s worth noting that more detuning (ie. adding voices) increases the CPU draw, since it effectively increases Thor’s polyphonic load.

Last of all, the noise generator is one of the more sophisticated examples I’ve seen this side of a stand–alone lab device. The full range of colours — white, pink, red and the rest, with all the in–between bits — can be generated.

Interaction between the oscillators includes amplitude (ring) modulation of Osc 1 by Osc 2, and oscillator sync. Osc 1 is a sync master, and two and three are the slaves, with a nifty ‘bandwidth’ control governing the depth of the ‘sync’ effect. Each oscillator has its own routing to control each of the two filters. The filter algorithms include a low–pass ladder, based on the classic Moog design, and a state–variable multi–mode filter that owes a lot to Oberheim’s SEM filter, plus comb and formant filters. The first two will self–oscillate in an authentically analogue fashion, and the formant filter is particularly welcome from my point of view.

These two filters can be operated serially or in parallel. The shaper module is fed from filter one, so if activated it treats the signal before the signal is processed by filter two. The waveshaping offered by this module could be thought of largely as distortion, but the changes it makes to basic waveforms can range from quite subtle to full–on destruction.

As pre–wired, the filter and amplitude envelope generators are bread–and–butter attack/decay/sustain/release devices with an option to disable standard triggering when using an alternative trigger source, via the modulation matrix. The modulation EG is a basic ADR design, but with a delayed onset parameter, the option to set up a loop between the delay and decay stages, trigger disable, and tempo sync’ing, where each stage of the envelope is a rhythmic value — subtle but potentially wacky.

A synth’s amplifier is seldom worth a serious mention, Thor’s likewise. The outputs of the two filters is mixed, gain adjusted (under velocity control, if desired) and pan position set. It’s this last parameter that is interesting. Thor isn’t a stereo synth as such — the oscillators or filters can’t be panned independently, for example — but there is a twist. Modulate the pan control (LFO is ideal) and each ‘voice’ played will be panned independently. Because the EGs are polyphonic, each panned voice will decay naturally, providing a cool stereo ‘hocket’ effect in extreme circumstances.

Going Global

From the amplifier, we’re into the global section, which has its own filter, envelope generator and LFO, plus a pair of effects. The global filter is identical in function to the other two, save that its envelope control is, initially at least, wired to the single–triggered global EG. That EG may just be single–triggered, but it has a few tricks worth playing with: the standard ADSR curve has a delay stage before and a hold stage after the attack, the delay–to–decay stage can be looped, and all stages can be tempo–sync’ed.

The two effects are simple: tempo–sync’ed delay and chorus. Apart from the delay’s tempo sync option, the two devices have the same parameters; they differ in the delay range — short delays for chorus, long for the delay. The effect is subtle to my ears, but both are mono in/stereo out, and thus tend to smear any panning or pan modulation you might have set up in the amp module.

The modulation routing window is potentially Thor’s biggest feature, but also one of its let–downs. I found it rather disappointing that only 13 patching busses were provided. They’re good, though, and come in three different varieties. Seven offer a straightforward source–to–destination routing, with a modulation amount parameter. Typical sources and destinations can be seen in the screenshots peppered around this review. In addition, a ‘scale’ parameter and value can be assigned. This configuration lets you, for example, assign LFO (source) to oscillator pitch (destination), under the control of modulation wheel (scale parameter), in which case LFO modulation will only be heard when the mod wheel is tweaked.

Four more busses work in the same way, except that the source is routed to two destinations, effectively doubling their effectiveness. The last two modulation busses have one source and one destination, but two scale parameters, allowing complex cross–modulation effects to be produced.

Finally, we come to the step sequencer — and its 16 step knobs are just the start. One row of 16 steps? I don’t think so — what you actually have are no fewer than six rows of 16 knobs, one each assignable to pitch, velocity, gate length, step duration, and two ‘curves’ which are picked up in the modulation matrix. Steps can be muted, and playback is one step each time Play is pressed, all steps in one go, or a looped playback. The steps can be played forward, backward, at random or in two pendulum modes. Best of all, the step sequencer doesn’t have to be sync’ed to the current song’s master tempo. Just like classic analogue modular devices, this step sequencer is free–running.

What we haven’t yet commented on is how good Thor sounds. Some of the analogue waveforms have the Propellerhead signature (ie. they sound like Subtractor), but beyond that you’re in completely new Reason territory. The sheer fun and sonic mayhem that’s possible with just Thor and the RPG8 arpeggiator can’t be expressed in words — and once you start routing Redrum and REX loops through the formant filter... well, I don’t know how I got the review done!

Break It Up

With the RPG8 monophonic arpeggiator, a picture says it all.The RPG8 Monophonic Arpeggiator is going to save a lot of Reason users a lot of trouble — and not before time. I can’t be alone in having tried to replicate this effect in various ways with existing devices. The results were often in the right ball park, and trying to get there revealed interesting programming possibilities, but the real thing is most welcome.

With the RPG8 monophonic arpeggiator, a picture says it all.The RPG8 Monophonic Arpeggiator is going to save a lot of Reason users a lot of trouble — and not before time. I can’t be alone in having tried to replicate this effect in various ways with existing devices. The results were often in the right ball park, and trying to get there revealed interesting programming possibilities, but the real thing is most welcome.

RPG8 immediately looks easy and straightforward to use — and it is — but this simplicity hides layers of sophistication that few other arpeggiators approach. Ah, the joys of software!

As a monophonic arpeggiator, RPG8 breaks up chords in various fashions: up, up plus down, down, random and manual. A hold function lets you input a chord and have it loop infinitely. However many notes you can input and hold down, RPG8 will arpeggiate them, over a range of between one and four octaves, with octave shifting and control over velocity response and step and gate length.

That’s the basic stuff. You also have control over patterns, whereby you can adjust the pattern length and disable steps. Like Thor’s step sequencer, RPG8 can be free–running, which is a great option when you’re using it as a modulation source rather than simply as a trigger for notes.

The back panel’s healthy collection of gate and CV ins and outs mean that more than just note and velocity can be transmitted; aftertouch, expression and breath control CV outs are produced, as well as a ‘start of arpeggio trig’. External sources can control gate length, velocity, resolution, octave shift and start of arpeggio trigger in. I was initially taken aback by a stack of buttons labelled ‘Insert’, but a little examination revealed that they add little variations to the RPG8’s output, by repeating notes in a certain way or by going forward and back in a predetermined way. RPG8 is monophonic, but layering the device with attached synths in a Combinator patch provides a pretty good stab at polyphonic–style arpeggiations.

There’s not much more to it: the notes to be arpeggiated can be live or previously recorded into a sequencer track, and there is a great option to record arpeggiations themselves to a sequencer track. And isn’t it great that there aren’t any drum pattern, guitar strum or piano comp preset patterns, as found on the average workstation synth?

Get Into The ReGroove

Looks aren’t everything with the ReGroove Real Time Groove Console — it hides a lot. Not surprising, since most of its funky stuff is edited somewhere else!For users who care about such things, the ‘groove’ and timing possibilities within Reason have long been adequate but not terribly advanced. The quantise tool was sufficient, without being hugely sophisticated, and the global ‘shuffle’ control was seldom completely groovy. In any case, it’s tied to certain devices and can’t be applied to sequencer tracks.

Looks aren’t everything with the ReGroove Real Time Groove Console — it hides a lot. Not surprising, since most of its funky stuff is edited somewhere else!For users who care about such things, the ‘groove’ and timing possibilities within Reason have long been adequate but not terribly advanced. The quantise tool was sufficient, without being hugely sophisticated, and the global ‘shuffle’ control was seldom completely groovy. In any case, it’s tied to certain devices and can’t be applied to sequencer tracks.

The brand–new, and rather unexpected, ReGroove Groove Mixer changes that without going too far in the auto–accompaniment direction. The new device lives just above Reason’s transport control section. It’s an initially baffling piece of technology — for me, anyway — but soon reveals its capabilities.

ReGroove offers four banks of eight ‘channels’, each of which plays one groove pattern and is assigned to affect the note playback of a sequencer track. You can assign a single channel/pattern to multiple sequencer tracks if you like. Each of the channels generates a user–tweakable, flexible groove template. You’re free to create your own or import one of several dozen presets. Of particular interest are those derived from Akai’s MPC60 sampling drum box, but there are loads of hip–hop, reggae and other miscellaneous options.

Press ‘edit’ in a ReGroove track and the Tool Window pops up, adding groove–setting parameters to the controls in the main window. The result can be as subtle, funky or obvious as you like, and not only will ReGroove add the desired shuffle or syncopation, but tracks can be made to push or lay back in the groove.

Global shuffle is an option, too, and this control (which can still be applied to the pattern–based devices) is now in the ReGroove window. Incidentally, should you want to apply the full ReGroove treatment to your ReDrum and Matrix patterns, they’ll need to have their performances bounced to a sequencer track first; they can’t be a target for one of the groove ‘tracks’. REX files, played by Dr:Rex, however, can be ReGrooved.

All Change

A closer look at the attractive new look of the sequencer. The new features found here move Reason closer to the sequencing facilities of DAW software.As much as we might love Reason, most of us would have to admit that the linear sequencer that lives just above the transport bar is not as well-developed as we would like. True, it’s just fine for chaining patterns and adding lead lines, and taking care of most straightforward work. But anything much more sophisticated has always had to be offloaded to a bigger sequencer hosting Reason in some way.

A closer look at the attractive new look of the sequencer. The new features found here move Reason closer to the sequencing facilities of DAW software.As much as we might love Reason, most of us would have to admit that the linear sequencer that lives just above the transport bar is not as well-developed as we would like. True, it’s just fine for chaining patterns and adding lead lines, and taking care of most straightforward work. But anything much more sophisticated has always had to be offloaded to a bigger sequencer hosting Reason in some way.

That situation is now history. The latest changes to Reason’s linear sequencer go well beyond mere tweaks. We’re talking complete rebuild here, and Reason is all the better for it. Track layout has been sweetened, the tool bar and tool window modified, and track colour–coding enhanced; there’s even a count–in option, enabled near the click controls.

Power users wondering if their years of begging for tempo and time signature tracks have been heeded can let out their breath. Propellerhead have implemented both, though the nifty way that tempo can be automated may be rather different from what you might expect: the transport bar is now more of a ‘device’ in its own right and can have its own sequencer track, and it’s here that tempo and time signatures are automated, just as easily as any other automation data. However, users who can’t understand why there is no audio recording option in Reason are destined for disappointment once again.

Next best improvements are to the sequencer track lists. They’re graphically cleaner, with better laid–out buttons (plus the odd new control, such as an automation record enable button), and support for grouped tracks. Now, data that’s being edited (notes, automation and what have you) is divided into individual lanes. It’s a better, and much more fun, way of doing the same job.

Lanes also come into play when doing multiple takes of a part, as you can stack takes and choose the best bits later. Recording a new part automatically creates a highlighted clip. Such grouped data would previously have had to be created manually.

New buttons enable automation recording, and data display is also different, and better. Changes have been made to the tool bar, making drawing data much easier than before, due in some part to differences in how that data is shown on screen. Even experienced users will have to take time to get re–acquainted with this side of things, though. It’s nice to have a razor-blade tool for slicing up grouped performances, but some functions are slightly hidden. Want the line tool? It’s now a hidden sub–function of the pencil.

Editing in general has been enhanced. Remember the floating tool window? It’s grown a bit, both in size and function. Most editing is now accessed here, including quantising (which has been removed from the sequencer window), note length, velocity, transposition, legato response and tempo scaling. Detailed ReGroove parameters also have their own window.

As if we didn’t have enough ways of adding new devices to the Reason rack, the tool window now has a sub–window for doing just this, via a list of graphics. It looks a little like Arturia’s Storm, but is a handy option.

One problem is that the sequencer tools display doesn’t have a scroll option to access the parameters that inevitably disappear off the bottom if loads of parameter groups are showing; the devices selection window does scroll, so perhaps this was a small oversight.

Putting It All Together

That’s it, in a nutshell. The new toys integrate with the rest of the rack as easily as if they’d been there all along, complete with logical automatic cable linking. But I advise you to go beyond the automatic: RPG8 has amazing potential as a source of general control voltages. The same could be said of Thor’s step sequencer; it might be a bit wasteful of CPU overhead to create an instance of this monster just for its sequencer, but if you’re already using it, you may as well get it linked to other devices.

That’s it for new devices, but a couple of existing instruments have also been tweaked. NNXT has been given new options to edit multiple samples at the same time, and there’s a new chromatic auto–map option. New samples are given a key group of one semitone each, without reference to root pitch, which is just fine for banging in loops and hits from your sample library.

Combinator, meanwhile gains a new transpose parameter that’s especially useful for getting note ranges right in splits. There are also more data filters, and helpful tweaks to the programmer.

Conclusion

All in all, Reason 4 is a pretty fine upgrade to what was already a powerful and desirable package. Operationally, the changes to the sequencer are, now that we have them, long overdue and really help to streamline that side of the package. Sonically, the addition of Thor means that Reason really ups its game. I could see some developers putting out this impressive piece of magnificent sound design as a stand–alone plug–in for a good proportion of Reason’s full asking price. As powerful, tweakable, and capable of helping you achieve your sonic goals as the rest of the rack is, Thor also goes several levels deeper.

I have similar feelings about the arpeggiator. I’m at a loss to explain why something as intrinsically naff as any arpeggiator should be so much fun, but there you go. RPG8 is a clever implementation of the beast, and I am so glad that Propellerhead didn’t go the extra mile in the way that workstation synth ‘arpeggiators’ do and add strumming, drumming auto–accompaniment.

The ReGroove mixer is not such a hit with me personally, though I can see how clever it is and appreciate that some will love it. Elsewhere, I can find very few negatives to this upgrade. Thor’s busy graphics became comprehensible quite quickly, and my initial brow–furrows regarding ReGroove smoothed out when I put myself in other users’ shoes. I like Propellerhead’s approach, right down to the cables. Mousing a device as complex as Thor can be a drag, and I’m glad that it’s so easy to integrate MIDI controllers with the rack so that the mouse can have regular rests. Serious users should budget for some form of hardware controller, since it makes the experience much more involving.

On the subject of audio input and recording, once again I have to report that Reason’s designers are perfectly happy with their software the way it is, and I’d say the vast majority of the user–base would echo that. The status quo — no audio — remains. What we have, then, is a must–have update for existing users and, in Thor, a device to tempt even the most recalcitrant of stand–backs. If you’re serious about electronic music, you should be serious about Reason.

System Requirements

The new toys and design in Reason 4 have had an impact in terms of system resources, especially if you’re using a DAW package as well. As with any CPU–hungry software, the minimum requirements are just that: minimum...

- Windows: Intel P4/AMD Athlon XP or better, 512MB RAM (1GB recommended), 2GB free disk space, Windows XP/Vista or later.

- Mac OS: G4 1GHz and up or Intel Mac, 512MB RAM (1GB recommended), 2GB free disk space, Mac OS 10.4.

On both platforms, you’ll need a monitor with a resolution of at least 1024x768 and a DVD drive for installation. Getting the best from the software will require better audio hardware than your computer will be equipped with, and a MIDI interface or controller of some kind will also probably be necessary.

Running Reason alongside other software is easy, since I can’t think of a serious digital audio workstation package that doesn’t support Propellerhead’s Rewire protocol. This links audio, MIDI and synchronisation between the two packages.

Old Reasons

To get up to speed on this universe called Reason, take a look at previous reviews on the SOS web site. The first version was reviewed back in March 2001, v2 in September 2002, v2.5 in December 2003 and v3 in May 2005.

Factory Music

New devices mean a new Factory Refill, and all the old material is joined by tons of new sounds, from a host of Reason fanatics that includes some major names. Both the Factory and Orkester Refills are provided on the single installation DVD, and the Factory set is very much enhanced. Thor and the RPG8 are nicely integrated into Combinator patches, with tons of examples of what these devices can get up to. The material seems to be better organised, too. Unravelling some of the more complex Thor and Thor/RPG8–based Combis can lead to some very interesting explorations.

There is just one singularly worrying trend: a whole folder of instant songs, called templates, though they’re no more templates than auto–accompaniment presets on home keyboards. Many start playing as soon as they’re loaded, and transpose in response to incoming MIDI notes. The up side is that anyone using Reason live will have instant bridge material in the event of emergencies or delays. Reason seems to do this sort of thing effortlessly, too: the equivalent patches or combinations that you’d find on current workstation synths often hog most of the available resources with the aim of impressing in the showroom. With Reason, they are just the beginning, if it’s a direction you’d like to go in.

It’s impossible to keep track of everything that’s new or different from previous Refills, but those who think Reason is digital and thin–sounding — I’m not one of them — will surely have to change their tune in response to the fatness, richness and depth of Thor’s factory patches.

Pros

- Thor. Full stop.

- Sequencer rebuild is tops.

- Love that RPG8 arpeggiator.

- While ReGroove isn’t exactly me, it could be you.

Cons

- Still no audio input/recording.

- Becoming rather demanding of host computer.

- RSI, here we come! Budget for hardware control.

Summary

The best keeps getting better. If you only buy one virtual studio, this should be it.

information

£299; upgrade from previous versions £69. Prices include VAT.M Audio UK +44 (0)1923 204010.

+44 (0)1923 204039.