Years before the Minimoog appeared, a Finnish visionary was already building digital polyphonic synthesizers — and they were controlled by light, skin conductivity and even brainwaves.

Following a stroke in 2006, Erkki Kurenniemi is now wheelchair-bound and unable to speak, though his mental powers are as acute as ever. This photo was taken in 2003.

Following a stroke in 2006, Erkki Kurenniemi is now wheelchair-bound and unable to speak, though his mental powers are as acute as ever. This photo was taken in 2003.

As readers of SOS will be aware, the synthesizer was pioneered by designers such as Robert Moog and Don Buchla in the late 1960s, and, while Moog and Buchla's creations differ from each other enough to be the basis of near-religious factions, they are all analogue and subtractive by nature. Every sound from these classic machines is made by modulating, attenuating and filtering the output of one or more analogue oscillators.

Far from the USA, however, a young Finnish pioneer of electronic music took a radically different approach. Erkki Kurenniemi could have changed the course of music history if he'd spent more time perfecting and selling his inventions, and less time looking at women and preserving used bus tickets for posterity. Kurenniemi completed a polyphonic synthesizer with digital sequencer in 1968, and a fully computer-controlled synthesizer in 1973 — and the ideas behind his user interfaces were even more innovative. Had those ideas taken off, logical binary keys, brainwaves and video scanning of dancing could have become natural ways of playing an instrument, and playing a synthesizer could have become a social activity, as some of Erkki Kurenniemi's instruments required four- or even 10-handed operation.

Brain Power

Erkki Kurenniemi's first instrument was the Integrated Synthesizer. Completed in 1967, it used pin-matrix programming on a huge scale. Photo: Kiasma

Erkki Kurenniemi's first instrument was the Integrated Synthesizer. Completed in 1967, it used pin-matrix programming on a huge scale. Photo: Kiasma

Erkki's mother was a writer of children's books, who taught her son to imagine invisible things like the trolls in the forest. His father was a chemist and mathematical analyst. From him, Erkki learned the scientific way of seeing the world. In the early 1960s, computers were gradually making their way into the world. Insurance companies, for instance, who were already using mechanical Hollerith machines (the foundation for IBM) with punched tapes for analysing numbers, were beginning to invest in the early 'electronic brains'. Through his father's work, Erkki was exposed to the world of natural science. Together, the two of them visited Bull Computer's production plant in France, and also saw atomic particle accelerators at universities in England.

The Andromatic was a digitally controlled polyphonic synthesizer, made in 1968 for Swedish composer Ralph Lundsten. Photo: Ralph LundstenThe 1960s also saw the dawning of electronic music production. Experimental composers were hijacking test equipment and pressing it into musical service. In the crypt-like basements of universities and national radio stations, oscillators and filters were mixed together with recordings of natural sounds on tapes that would later be cut and spliced into mosaics of sound under the names Musique Concrète and, later, Electronic Music. Most such studios were developed by enthusiastic technicians who helped young experimental composers to realise their ideas. More often than not, experimental works were put together late at night, in studio down-time.

The Andromatic was a digitally controlled polyphonic synthesizer, made in 1968 for Swedish composer Ralph Lundsten. Photo: Ralph LundstenThe 1960s also saw the dawning of electronic music production. Experimental composers were hijacking test equipment and pressing it into musical service. In the crypt-like basements of universities and national radio stations, oscillators and filters were mixed together with recordings of natural sounds on tapes that would later be cut and spliced into mosaics of sound under the names Musique Concrète and, later, Electronic Music. Most such studios were developed by enthusiastic technicians who helped young experimental composers to realise their ideas. More often than not, experimental works were put together late at night, in studio down-time.

In Finland, too, the spark of electronic music had been ignited. At the Institute of Musicology at Helsinki University, professor Erik Tawastjerna wanted to establish an Electronic Music studio. To keep costs down, and because very little was commercially available, much of the equipment would have to be built locally. In 1961, Erkki Kurenniemi, who studied physics at Helsinki University, was hired for the task. The budget did not allow for actually paying Kurenniemi for his work, but he was allowed to keep some of the components for his own projects and granted considerable freedom to innovate.

Completed in 1968, the Electric Quartet was designed to be played by four musicians and a singer, using push buttons, light-sensitive resistors, patch cables and a microphone. Photo: John Alex HvidlykkeAt this time, the concept of an electronic music studio was only loosely defined, and there was no standard list of equipment that such a studio should contain. When Kurenniemi was included in the project, three Telefunken M24 studio tape recorders had been ordered. He bought lots of electronic components and several Heathkit construction kits for building tone generators, filters and a ring modulator. He also bought an oscilloscope and a spring echo. Later, the studio acquired two Studer tape recorders, one of which was equipped with a stereo tape head. When fully up and running in 1972, the studio also included a pair of EMS VCS3 synthesizers, along with Kurenniemi's own creations.

Completed in 1968, the Electric Quartet was designed to be played by four musicians and a singer, using push buttons, light-sensitive resistors, patch cables and a microphone. Photo: John Alex HvidlykkeAt this time, the concept of an electronic music studio was only loosely defined, and there was no standard list of equipment that such a studio should contain. When Kurenniemi was included in the project, three Telefunken M24 studio tape recorders had been ordered. He bought lots of electronic components and several Heathkit construction kits for building tone generators, filters and a ring modulator. He also bought an oscilloscope and a spring echo. Later, the studio acquired two Studer tape recorders, one of which was equipped with a stereo tape head. When fully up and running in 1972, the studio also included a pair of EMS VCS3 synthesizers, along with Kurenniemi's own creations.

It was these creations that were truly remarkable. Having been raised in the company of computers since childhood, Erkki took a truly original approach to his constructions. Most importantly, he chose to have the generation and delivery of sounds controlled digitally, which no one had ever done before. Between 1964 and 1967, he built his so-called Integrated Synthesizer, which contained a digital sequencer in addition to its digitally controlled oscillators.

Looking more like a piece of industrial equipment than a musical instrument, the DICO was an innovative digitally controlled synthesizer from 1969.Photo: John Alex HvidlykkeKurenniemi also composed several pieces, most of which were improvised in the studio. He considers his first piece, 'ON/OFF' from 1963, to be his best. The name reflects the idea that in the future, automated computer-based composition will mean that the only user control necessary will be a power switch to start and stop the recording. "And,” he says, "when files are supplanted by continuous audio streams, even that switch will become unnecessary.”

Looking more like a piece of industrial equipment than a musical instrument, the DICO was an innovative digitally controlled synthesizer from 1969.Photo: John Alex HvidlykkeKurenniemi also composed several pieces, most of which were improvised in the studio. He considers his first piece, 'ON/OFF' from 1963, to be his best. The name reflects the idea that in the future, automated computer-based composition will mean that the only user control necessary will be a power switch to start and stop the recording. "And,” he says, "when files are supplanted by continuous audio streams, even that switch will become unnecessary.”

Philosophising in 1967, he said: "The computer composers of the future can be compared with today's industrial designers, rather than artists. This may sound depressing now, but the world of today may have sounded equally unsettling for people a hundred years ago. And yet most of us are quite happy with our present way of life.” Whether the computer-generated music of the future would be able to compete with humanly created music was a different matter. "But I do know that computer music eventually will be much cheaper to make.”

An Alternative Vision

The first instrument built under the Digelius banner was the DIMI-A, another innovative digital synthesizer which was played using two probes.Photo: John Alex Hvidlykke

The first instrument built under the Digelius banner was the DIMI-A, another innovative digital synthesizer which was played using two probes.Photo: John Alex Hvidlykke

Erkki Kurenniemi's instruments were, in many respects, years ahead of the competition, and the synthesizer industry might have turned out differently had they been brought to production in higher volumes. In 1970, Kurenniemi founded a company called Digelius, using help from the Finnish Innovation Fund, SITRA, with the intent of manufacturing his DIMI instruments. The SITRA grant was provided to help the commercialisation of DIMI-A, but it also gave Kurenniemi the possibility to develop the DIMI-O and later machines. A working sample of DIMI-O was built, and the long-haired and wild-eyed business owner explained in a promotional film how instruments like DIMI-O would change the way music was played.

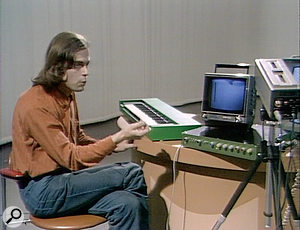

A still from a promotional film in which Erkki Kurenniemi explains the potential of his DIMI-O optically controlled synthesizer.Although highly innovative as a constructor and composer, Digelius only sold a few instruments and Kurenniemi was a complete disaster as a businessman — or perhaps the world was simply not ready for an instrument that had to be played by body movement as the image from a video camera was scanned for positions that could be interpreted as musical notes. The DIMI-O on the promotional video was the only one ever built, while the beautifully designed DIMI-A, at least, was twice as numerous. Besides building innovative synthesizers in single-digit numbers, Kurenniemi was known throughout the Nordic region as an expert on digital equipment. So, while waiting for a commercial breakthrough, he drove around in his rusty Citroën 2CV, fixing early computers and thus providing an income to the company.

A still from a promotional film in which Erkki Kurenniemi explains the potential of his DIMI-O optically controlled synthesizer.Although highly innovative as a constructor and composer, Digelius only sold a few instruments and Kurenniemi was a complete disaster as a businessman — or perhaps the world was simply not ready for an instrument that had to be played by body movement as the image from a video camera was scanned for positions that could be interpreted as musical notes. The DIMI-O on the promotional video was the only one ever built, while the beautifully designed DIMI-A, at least, was twice as numerous. Besides building innovative synthesizers in single-digit numbers, Kurenniemi was known throughout the Nordic region as an expert on digital equipment. So, while waiting for a commercial breakthrough, he drove around in his rusty Citroën 2CV, fixing early computers and thus providing an income to the company.

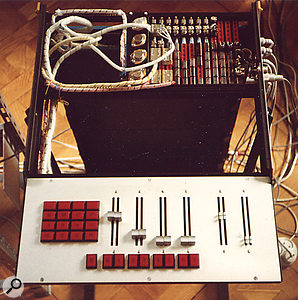

The DMIX was an early and typically innovative attempt to create an automated mixer.The last product to be constructed by Digelius was DIMI-6000, a computer-controlled (this was in 1973!) analogue synthesizer. Like several later computer-controlled behemoth synths, the gigantic effort sunk Digelius. Two DMI-6000s were built, and neither of them is functional today, as the operating system has been lost. In hindsight, naming the operating software DISMAL (Digelius System Music Assembly Language) was perhaps begging for nemesis to strike!

The DMIX was an early and typically innovative attempt to create an automated mixer.The last product to be constructed by Digelius was DIMI-6000, a computer-controlled (this was in 1973!) analogue synthesizer. Like several later computer-controlled behemoth synths, the gigantic effort sunk Digelius. Two DMI-6000s were built, and neither of them is functional today, as the operating system has been lost. In hindsight, naming the operating software DISMAL (Digelius System Music Assembly Language) was perhaps begging for nemesis to strike!

After his ill-fated adventure as a musical instrument manufacturer, Kurenniemi worked from 1976 to 1978 as a robotic designer for Rosenlew, a Finnish manufacturer of refrigerators, harvesters — and robots. Later, between 1980 and 1986, he worked for Nokia, again designing robots. Finally, from 1987 to 1998, Kurenniemi became head of planning at the Science Centre in Vantaa, Finland, teaching science to children and older students.

The Obscure Archive

Another Erkki Kurenniemi instrument designed for social music-making was the DIMI-S 'Sexophone'. Four musicians could produce different tones by touching its controls — and each other!Photo: Ralph Lundsten

Another Erkki Kurenniemi instrument designed for social music-making was the DIMI-S 'Sexophone'. Four musicians could produce different tones by touching its controls — and each other!Photo: Ralph Lundsten

Since the introduction of the first microprocessors in the early 1970s, digital technology has doubled in complexity roughly every 18 months. This pace of development is known as Moore's Law, named after Intel founder Gordon Moore, who first phrased the prediction. According to futurists like Erkki Kurenniemi and fellow synth pioneer Raymond Kurzweil, this will inevitably lead to a point known as the Singularity, where the typical computer is as fast and complex as the human brain. As development continues beyond this point, some years later an off-the-shelf computer will be powerful enough to emulate the thought processes and consciousness of a human, which will enable us to escape mortality by taking a backup copy of our own mind and living on inside ever more powerful computers. According to Kurzweil, this will happen in 2047, while Kurenniemi sets the year to 2048! Kurenniemi predicts that in 2040 the computer will be as powerful as the human brain, and that by 2060 a computer could be as powerful as the brain power of the whole of humanity together.

The DIMI-T was a synthesizer controlled by brain waves.Erkki Kurenniemi has believed for decades that the days of old-fashioned biological life are coming to an end. He foresees a near future where life as we know it will be exchanged with eternal, virtual life inside a gigantic supercomputer more powerful than the amassed brain power of humanity. To Kurennimi and other futurists, such a step is merely logical. Why hold on to fragile and slow "slime-based” processing, when something superior becomes available? When that time comes, we might become bored inside our computer reality, wondering what it's like to live in a biological body. For the purpose of answering that question to future generations, and to create a backup of his mindset, Kurenniemi began the task of making a complete recording of his old-fashioned physical life. Kurenniemi suggests that a digital emulation of his mind, based on his recordings, can be started on 10th July 2048, on his 109th birthday.

The DIMI-T was a synthesizer controlled by brain waves.Erkki Kurenniemi has believed for decades that the days of old-fashioned biological life are coming to an end. He foresees a near future where life as we know it will be exchanged with eternal, virtual life inside a gigantic supercomputer more powerful than the amassed brain power of humanity. To Kurennimi and other futurists, such a step is merely logical. Why hold on to fragile and slow "slime-based” processing, when something superior becomes available? When that time comes, we might become bored inside our computer reality, wondering what it's like to live in a biological body. For the purpose of answering that question to future generations, and to create a backup of his mindset, Kurenniemi began the task of making a complete recording of his old-fashioned physical life. Kurenniemi suggests that a digital emulation of his mind, based on his recordings, can be started on 10th July 2048, on his 109th birthday.

Erkki Kurenniemi compulsively archived details of his life, believing that advances in computing power will make it possible to recreate his mind in software sometime in the middle of this century.Photo: John Alex Hvidlykke

Erkki Kurenniemi compulsively archived details of his life, believing that advances in computing power will make it possible to recreate his mind in software sometime in the middle of this century.Photo: John Alex Hvidlykke

In order to able to make as complete a computer emulation of himself and his thoughts as possible, Erkki made records of his observations though most of his life. His archives number a staggering amount of notebooks, scrapbook clippings, video tapes, audio cassettes and digital images. For years, he carried a camera and took random pictures of what he saw every few minutes during his waking hours. He also carried a dictaphone recorder for taking mental notes. During this process, he made great efforts not to be distracted by his own subjective views of relevance, but recorded his observations completely at random. Bus tickets and pictures of the streets he drove down on his many nightly car trips were as important to him as discussions and meetings. This also means that facts that would be considered important by many are often missing. A researcher working on Kurenniemi's archive was excited to find that several cassette tapes existed from the day of a particularly interesting lecture. It turned out that Kurenniemi had faithfully made tape recordings on his long commute to the university, but stopped the recorder when entering the building. Then, after giving his lecture, Kurenniemi resumed the recording by reciting car number plates on the way back home!

The last Digelius hardware synthesizer was the DIMI-6000, a hugely advanced instrument controlled by computer. Sadly, the operating system has been lost and the instrument does not work any more.Photo: KiasmaBesides requiring a lot of effort from himself, Kurenniemi's manic passion for archiving must have affected those around him. Being close to him meant that you would be recorded and photographed constantly for the purpose of being included in his giant archive, especially if you were one of Erkki's many female acquaintances. Among his many pastimes, Kurenniemi was deeply interested in pornography. Not for secret kicks, but genuinely collecting, watching and discussing pornographic movies as if they were the latest arthouse movie fresh from the Cannes Festival. Kurenniemi also registered his many female acquaintances, taking notes in notebooks, pasting in pubic hairs and commenting on the quality of the experience. Interestingly, Erkki's more personal notes were done in Finnish, while his scientific theories were written in English, the two languages often mixed on the same page.

The last Digelius hardware synthesizer was the DIMI-6000, a hugely advanced instrument controlled by computer. Sadly, the operating system has been lost and the instrument does not work any more.Photo: KiasmaBesides requiring a lot of effort from himself, Kurenniemi's manic passion for archiving must have affected those around him. Being close to him meant that you would be recorded and photographed constantly for the purpose of being included in his giant archive, especially if you were one of Erkki's many female acquaintances. Among his many pastimes, Kurenniemi was deeply interested in pornography. Not for secret kicks, but genuinely collecting, watching and discussing pornographic movies as if they were the latest arthouse movie fresh from the Cannes Festival. Kurenniemi also registered his many female acquaintances, taking notes in notebooks, pasting in pubic hairs and commenting on the quality of the experience. Interestingly, Erkki's more personal notes were done in Finnish, while his scientific theories were written in English, the two languages often mixed on the same page.

Art & Science

Erkki Kurenniemi began his career as an instrument maker when he was commissioned to build an electronic music studio for the Institute of Musicology in Helsinki.

Erkki Kurenniemi began his career as an instrument maker when he was commissioned to build an electronic music studio for the Institute of Musicology in Helsinki.

Taken as a whole, Erkki Kurenniemi's body of work is staggering. While none of his synths really ever made it past the prototype stage, they were revolutionary in their ideas and technology. In 2003, Kurenniemi received the Finland Prize from the ministry of education and culture, and in 2004 he was elected an honorary fellow of the University of Art and Design in Helsinki. Kurenni was awarded the Order of the Lion medal in 2011 by the president of Finand, Mrs Tarja Halonen.

Several of Erkki Kurenniemi's instruments were commissioned by Ralph Lundsten for his Andromeda Studio. This photo shows the studio in 1984. Photo: Ralph LundstenErkki Kurenniemi suffered a stroke in 2006, rendering him half paralysed and without speech. His mental powers are, however, intact, and he can enjoy being the subject of interest from researchers and electronic musicians, who recognise him as a pioneer whose work is every bit as important as that of synthesizer creators from the USA and the rest of Europe. Kurenniemi's machines have been on display on art exhibitions in Kassel, Germany and Aarhus, Denmark, and will, from November 2013, be displayed at the Kiasma art museum in Helsinki. After more than 40 years, some of the Kurenniemi machines are broken beyond repair, but others are kept in working order by the scientists at Kiasma, who also have performed with the machines on special occasions (see, for instance, http://vimeo.com/60042419).

Several of Erkki Kurenniemi's instruments were commissioned by Ralph Lundsten for his Andromeda Studio. This photo shows the studio in 1984. Photo: Ralph LundstenErkki Kurenniemi suffered a stroke in 2006, rendering him half paralysed and without speech. His mental powers are, however, intact, and he can enjoy being the subject of interest from researchers and electronic musicians, who recognise him as a pioneer whose work is every bit as important as that of synthesizer creators from the USA and the rest of Europe. Kurenniemi's machines have been on display on art exhibitions in Kassel, Germany and Aarhus, Denmark, and will, from November 2013, be displayed at the Kiasma art museum in Helsinki. After more than 40 years, some of the Kurenniemi machines are broken beyond repair, but others are kept in working order by the scientists at Kiasma, who also have performed with the machines on special occasions (see, for instance, http://vimeo.com/60042419).

Kurenniemi's Machines: The Early Years

None of Erkki Kurenniemi's synthesizers was manufactured in high volumes. They were, however, groundbreaking experiments into new ways of musical expression, as nearly every synth he made introduced a completely new user interface. Oh yes, and Kurenniemi also invented the first digital synthesizer, the first real polysynth, the first digital sequencer and the first computer-controlled synthesizer!

Most of Kurenniemi's instruments were unique, while three of them were built in pairs. In total, Kurenniemi only ever built 13 instruments, most of which are kept in working order by museums and collectors. The Musicology department at Helsinki University today owns the Integrated Synthesizer, Electronic Quartet, DICO, DIMI-A, Dimix and DIMI-6000. The Museum of Music in Stockholm has another DIMI-A. Swedish musician Ralph Lundsten, who commissioned several instruments from Kurenniemi, holds on to his DIMI-S, DIMI-O and Andromatic instruments.

- Integrated Synthesizer (1964-1967)

For anyone building an electronic studio in the 1960s, a new Moog modular synthesizer was high on the wish list, but the price tag was even higher. Since the Institute of Musicology had no funding for a full modular system, Erkki set out to construct his own. He had no access to Moog's schematics, so he had to use whatever material he found available, including Moog brochures and transistor circuit manuals. The Integrated Synthesizer was to consist of a Generator Unit (oscillator), Filter Unit and a Mixer. Kurenniemi employed whatever sound processing circuits he could find, analogue as well as digital. Integrated circuits were not available in Finland at the time, so instead he found some epoxy-encapsulated logic circuits, gates and flip-flops from Philips. These were originally intended for use in calculators, but Kurenniemi used them in his Generator Unit, both for audio and control signals. The sound generator was programmable through a 500-point pin matrix, like the (later) EMS VCS3. Erkki presented his Generator in 1964 at the Jyväskylä Summer Festival for algorithmic music, while the whole project took yet another three years to complete. The Integrated Synthesizer is now at the Kiasma art museum in Helsinki.

- Andromatic (1968)

This synthesizer was a commission for Swedish musicians Ralph Lundsten and Leo Nilson and their Andromeda Studio. Andromatic was a 10-voice polysynth with built-in digital sequencer — in 1968! The massive rackmounted unit featured 10 (analogue) tone generators, connected with filters and modulation options. The main feature, however, was the built-in digital sequencer. Through a variety of rather curious setup options, the Andromatic could produce a sequence of tones with a length from 10 (working in polyphonic mode with one generator per step) to 1024 steps (in monophonic mode).

The Andromatic was groundbreaking in several ways. It was the first solid-state polyphonic synthesizer in the world (and, barring the 1939 Hammond Novachord, the first true polysynth), and it was the first synth equipped with a digital sequencer. What's more, the sequencer could control not only sound but also light. Even after more than 40 years of use, the Andromatic is still in active use by Lundsten in his studio in Stockholm's archipelago.

- Electric Quartet (1967-1968)

As the name implies, the Electric Quartet (Sähkökvartetti in Finnish) was designed to be played by four musicians simultaneously, together with a vocalist. The four would play 'keys', of which some were push buttons and others were holes in front of light-sensitive resistors. For the singer, a microphone offered distorted input. A banana-plug patch panel on the side of the instrument enabled musicians to reconfigure the instrument completely.

As with any other Kurenniemi instrument, playing the Electric Quartet was no simple matter. The 'keyboards' were not chromatic, but binary, and the four playes not only shared the same instrument, but also had direct influence over each other's sounds! The Electric Quartet was built for MA Numinen and his experimental band, and now belongs to Kiasma.

- DICO (1969)

DICO (Digitally Controlled Oscillator) was built for the Finnish electronic music pioneer Osmo Lindeman. As the name implies, the tone-generating circuitry was digitally controlled. The memory of the huge rackmounted apparatus was 12 words (bytes) of 10 bits each, thus providing a 12-step digital sequencer. Four bits of each byte controlled the pitch, while three set the octave, giving the oscillator an eight-octave range. Two further bits set the length of the tone, and one bit set the output channel. Programming of the sequence was done step by step, by making electrical contact with one of 36 metal pins on the front, arranged in a 3x12 matrix. To add some randomness to the programming, contact was made with a metal brush, giving a certain amount of uncertainty as to which point was connected.

Kurenniemi's Machines: The Digelius Instruments

Most of Erkki Kurenniemi's instruments carry the name DIMI (DIgital Music Instrument). Every single DIMI-series instrument was controlled in a new and entirely different way. Touch, light, skin conductivity, body motion and even brainwave activity were used for artistic expression.

- DIMI-A (1970)

At the dawning of the information age, the idea of controlling synthesizers from a computer had obvious appeal, but the price tag on the early 'electronic brains' made them unobtainable for anybody but the biggest institutes and private enterprises. Instead, Erkki Kurenniemi set out to make an instrument just as powerful as a real computer, yet more affordable. The A in DIMI-A stands for 'Associative memory', which is a different way of storing digital information in a computer. Conventional random access memory consists of a number of locations with individual addresses; to recall a particular piece of information, you need to know what address to inspect. With an associative memory, by contrast, the user searches for a particular piece of data, and the memory returns one or more addresses where that data can be found. DIMI-A was the first instrument to be built by Digelius Electronics and was Kurenniemi's most aesthetically designed instrument. Still, the user interface was characteristically different from everything else. Programming was done with two probes on a touchpad, but there was no clue as to what linked the contact points and the tones that resulted.

- DIMI-O (1971)

The most technically advanced of the DIMI instruments was the DIMI-O. The 'O' stood for Optical, and the interface employed a camera which was used to trigger notes on the synthesizer. Different positions on the screen translated into different note values. The original idea was that the DIMI-O would be able to read sheet music directly, but in the end, DIMI-O was triggered by movements of a dancer, interpreting positions on the stage into musical notes. The only prototype of the DIMI-O ever made now resides in Ralph Lundsten's studio. An original video of Erkki Kurenniemi and a dancer demonstrating the instrument can be found here: www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=d-yHULQ2V5c

- DIMI-S (1972)

The DIMI-S 'Sexophone' is a group participation instrument that can be played by up to four people simultaneously. Sound is generated by having the players touch the four conductive handles — and also each other. The timbre produced by the DIMI-S depends on the resistance between the different handles and by the conductivity of the four players' skin. Six flickering light bulbs accompany the sound, giving DIMI-S an amusement park-like appearance. The more skin is exposed, the more sonic expression is possible with the instrument, hence the name 'Sexophone'. Two DIMI-Ss were built, and both are still working today. One is at Kiasma and the other is owned by Ralph Lundsten.

- DIMIX (1972)

The missing dash in the DIMI name is not a typographical error. DIMIX was not a synthesizer, but a digitally controlled mixer and patchbay, making it possible to automate the task of mixing in an electronic studio.

- DIMI-T (1973)

Not content with a merely body-related interface, Erkki tried to connect the musician's brain directly with the instrument. DIMI-T, dubbed the 'Electroencephalophone', was played with brain waves, picked up by electrodes on the player's earlobes. In spite of the name, DIMI-T was not digital, but analogue in nature. The EEG signal from the user's brain waves was amplified, band-pass filtered and used to frequency-modulate a VCO inside. DIMI-T was intended for group use. A quartet of musicians, each equipped with a DIMI-T, would go to sleep listening to each other's generated sounds, and Kurenniemi envisioned that their brainwaves would synchronise during sleep. That test was never done, however.

- DIMI-U (never built)

Both the DIMO-O and the DIMI-A were technologically innovative, and so were their highly experimental user interfaces. The DIMI-U was supposed to have been a combination of the technologies in the two instruments. However, at that time real computing power was finally becoming available to small-scale industries, so Erkki Kurenniemi chose to stop developing the DIMI-U in favour of a fully computer-controlled instrument.

- DIMI-6000 (1973)

The DIMI-6000 was Kurenniemi's last hardware synthesizer, and was, for the time, tremendously advanced. The sound-generating circuitry was analogue and voltage-controlled, but everything was governed by a genuine microcomputer, based on the then newly developed Intel 8008 microprocessor (an 8-bit processor and a distant predecessor of today's PC processors). The computer, which featured a built-in display and a cassette recorder for data storage, was connected to a stack of hardware boxes, containing the synthesizer itself, the D-A and A-D interface and switching matrix. Two DIMI-6000s were built before Digelius went bankrupt.

- DIMI-H (2005)

Like several other pioneering electronic composers and inventors, Erkki Kurenniemi's solitary work in the 1960s and 1970s finally received recognition decades later. This led him to resume work on his instruments, and in 2005 Kurenniemi designed his final DIMI-series instrument. The DIMI-H (www.beige.org/projects/dimi/) is a software-based instrument which encapsulates Erkki's theories on mathematical harmonisation. As with every other DIMI, this one also featured a novel method of interaction. The DIMI-H was played in a three-dimensional space in free air, where two cameras picked up the movements of a musician's hands. It was made in collaboration with UK-based designer Thomas Carlsson for an event in Helsinki.