David Reitzas and his extensive collection of outboard processors.Photo: by Damon Gramont

David Reitzas and his extensive collection of outboard processors.Photo: by Damon Gramont

The making of Barbra Streisand’s latest hit album, Encore, offers a window into the unique philosophy of hit-making producer and engineer David Reitzas.

“I absolutely love what I do,” says David Reitzas. “When I am in a studio, I’m in an incredibly beautiful environment, with great gear, sitting in front of fantastic speakers. I don’t take working in a studio for granted for a second. To me the most valuable thing is to be in a studio and use my 30 years of experience in using every tool that I have to try and help an artist realise their vision, whether it’s Barbra Streisand or Chris Cornell or the Weeknd. I get a kick out of working with people, and it doesn’t have to be with the biggest artist in the world, it could be anyone who is serious about making a great record. I just really enjoy the process of making records.”

Reitzas is talking from Westlake Studio E, where he spends a lot of his time. As one of the world’s foremost engineers and mixers, Reitzas has a lot to be proud of. His credit list is awash with household names, ranging from Guns N’ Roses to Madonna, from Céline Dion to Whitney Houston, and his work has earned him four Grammy Awards and an Emmy Award. He’s arguably best known for his work with Barbra Streisand, which began in 1993 when he was an engineer on Streisand’s 26th studio album Back To Broadway.

Reitzas is talking from Westlake Studio E, where he spends a lot of his time. As one of the world’s foremost engineers and mixers, Reitzas has a lot to be proud of. His credit list is awash with household names, ranging from Guns N’ Roses to Madonna, from Céline Dion to Whitney Houston, and his work has earned him four Grammy Awards and an Emmy Award. He’s arguably best known for his work with Barbra Streisand, which began in 1993 when he was an engineer on Streisand’s 26th studio album Back To Broadway.

This album was produced by David Foster and Andrew Lloyd Webber, just two of the many legendary studio names Reitzas has worked with; others include Tommy LiPuma, Mutt Lange, Phil Ramone, Arif Mardin, William Orbit and Walter Afanasieff. His most influential mentor was Foster, with whom he worked with exclusively from 1987 to 1994, and on numerous projects since, clocking up credits like Whitney Houston, Natalie Cole, Michael Bolton, and, of course, Céline Dion and Barbra Streisand.

Foster: Father Figure

When a young David Reitzas travelled to Los Angeles in 1984, he did not have a studio career in mind. Reitzas grew up in Massachusetts, where he took an engineering class at Bristol Community College, and studied music at the University of Rhode Island and Boston’s Berklee School Of Music. His plan was to blitz LA for the technical knowledge he needed, then return to Massachusetts and make it big as a rock & roll drummer. After arriving in LA, Reitzas worked his way up from tape-op to assistant at Cherokee Studios, Sound City, and finally at Rumbo Studio, where he had the good fortune to assist producer Mike Clink in the making of Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite For Destruction (1987). A young David Reitzas at Chartmaker Studios, 1987.

A young David Reitzas at Chartmaker Studios, 1987.

Clink recommended the young engineer to David Foster, and Reitzas has remained in LA ever since. Reitzas went independent in 1995, and participated in the making of classic albums such as Natalie Cole’s Unforgettable (1991), Frank Sinatra’s Duets (1993), Whitney Houston’s The Bodyguard (1992), Céline Dion’s The Colour Of My Love (1993), Madonna’s Ray Of Light (1996), Shakira’s Laundry Service (2001), Josh Groban’s Closer (2003), Seal’s Soul (2008), and the Weeknd’s Beauty Behind The Madness (2015).

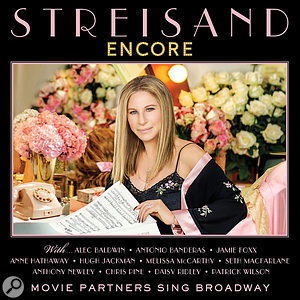

There’s also the small matter of Reitzas playing a central role in the making of an impressive 18 Barbra Streisand albums and all of her live recordings and mixing since her return to the stage in 1994. This number includes Streisand’s latest album, Encore: Movie Partners Sing Broadway. Her 36th studio album, Encore was released in August and reached number one in the US, the UK and Australia. It was Streisand’s 11th number one album in the US, putting her behind only the Beatles and Jay-Z in the all-time list.

Legendary producer David Foster (left) has been David Reitzas’ mentor since the early 1980s.

Legendary producer David Foster (left) has been David Reitzas’ mentor since the early 1980s.

Point Of Departure

On her previous studio album, Partners (2014), Streisand had partnered up with more prototypical singers, like Michael Bublé, Andrea Bocelli, and even Elvis Presley (using a 1956 vocal recording), but for the mixture of dialogue and singing on Encore, Streisand opted to work with a more motley crew of actors and even comedians, not all of them known for their singing, amongst them Anne Hathaway, Hugh Jackson, Melissa McCarthy, Antonio Banderas, Chris Pine and Jamie Foxx. The album was produced by Streisand with Walter Afanasieff, who, along with William Ross, took care of the musical arrangements, which feature a full orchestra and a band. David Reitzas once again brought his considerable experience to the recording and mixing controls.

Reitzas: “Walter started in the Summer of 2015 by making instrumental demos for a number of the songs. He does this at his studio, WallyWorld, which is a very nice home studio above his garage, where he has a Pro Tools Icon, Pro Tools HD, as well as Logic. My involvement started not long afterwards with me going to Barbra’s house and recording some of the dialogue parts for a number of the songs. That was the early stages of creating a kind of dialogue road-map. She performed all the parts of the female vocals, and Walter or her husband [James Brolin] did the male vocal parts. Barbra has her own microphone, a Blue Neumann M49, and I bring my Mäag PREQ4, Mäag EQ4, a Tube-Tech CL1B compressor, a Bricasti M7 reverb, and my laptop with Pro Tools. I also brought my wireless Audio-Technica AE5400, so Barbra could use that while sitting in the room with me, Walter, Jim, and Jay Landers, and not have to be in front of a mic stand all the time.

“At this point we were working with Walter’s demos for us to start to figure out the arrangements. Walter did most of the demos with his main engineer Tyler Gordon, and Bill Ross also did some at his Momentum Studio with Mary Webster. The process is that I load their demos as audio into Pro Tools. I spend time with these demos, making them sound as good as I can, so we can keep building the songs and figuring out the arrangement while we record vocals. Sometimes we would build a demo before we knew who was going to sing on the song, so once it was decided who was going to sing on it, we had to work out the keys that are best for the singer or singers, which meant that we might have to replace a whole section in the demo, using a different key and with new transitions to get to that key. The arrangements are constantly evolving, and Walter and Bill later in their studios changed the MIDI to match the changes I made to the audio.”

Sing Up

The next stage in the making of Encore was for the company to start recording the actual vocals, both dialogue and singing. Most of the vocal recordings took place at Woodshed Recording in Malibu, a gorgeous studio with a homely interior full of wood, and spectacular views of the surrounding hills and the Pacific. There are many YouTube videos that show Streisand in sessions with the various vocal performers at this exceptionally photogenic place, directing them, coaxing good performances out of them, and trying out new things.

According to Reitzas, the vocal sessions there started on February 12th, 2016 (his birthday), and continued off and on over the next couple of months. “The first session was with Jamie Foxx and Barbra singing ‘Climb Every Mountain’. Following that we recorded ‘At The Ballet’, ‘Loving You’, ‘Pure Imagination’, ‘Losing My Mind’ and ‘Who Can I Turn To?’, the duet with the late Anthony Newley. I recorded most of the duet partners with a Neumann U47, going through a Neve 1272, and that was it, no compression or EQ on the way in. For Melissa McCarthy only, I used an Audio-Technica AT4060 with custom tubes that I’ve had fitted. Singers usually sang using Audio-Technica ATH-M50 headphones, which Barbra and I like to use, apart from Seth McFarlane who used his iPhone earbuds. For monitoring, the singers had control of the overall level and talkback. We spent a lot of time on the vocals, trying them one day, picking the best ideas, trying them again another day, and so on, until we felt comfortable with the most honest readings.

David Reitzas’ portable setup for recording Barbra Streisand’s vocals included (top) a Tube-Tech CL1B compressor and Bricasti M7 reverb; and Mäag PreQ4 and EQ4 500-series modules.

David Reitzas’ portable setup for recording Barbra Streisand’s vocals included (top) a Tube-Tech CL1B compressor and Bricasti M7 reverb; and Mäag PreQ4 and EQ4 500-series modules.

“In between sessions I would not only be reviewing vocals, but I’d also be editing Walter’s or Bill’s demos, working on their next sets of demos, and also rough mixing so we could keep track of our progress. I did most of the vocal reviewing at Barbra’s place with her, and also spent a lot of time at my house, which I call The Chandelier Room, with my M50 headphones or my Genelec 8320 monitors. I brought either the Genelec 8351s or the 8320s with me as my monitors throughout the record. They have the SAM calibration system, which made it possible to have an accurate, consistent sound wherever I went. At this point I was working 100 percent ‘in the box’, and I purposely kept my sessions with as few plug-ins as possible, so that I would not have any problems when I would go to a different studio. For example, we later also recorded Alec Baldwin’s and Hugh Jackman’s vocals in New York at MSR, and we monitored Chris Pine’s vocals from Angel Studios and Antonio Banderas’s vocals from AIR Studios in London. Knowing that throughout the project I would be using various Pro Tools systems, I didn’t want to waste any time on making each system compatible with multiple plug-ins, or by making my rough mixes too good and hard to beat later on.”

Almost Final

The vocal recordings had been tracked to Afanasieff’s and Ross’s orchestral mock-ups, which were continuously adapted to the vocal recordings until final arrangements were in place for the live orchestra and rhythm tracking sessions. Those took place for 10 of the songs over three days in early April 2016 at the Barbra Streisand Scoring Stage at Sony Pictures Studios, with engineers Dave and Matt Ward, and for the few remaining songs on one day in mid May at the Newman Scoring Stage at Fox Studios, with Dave Ward and Armin Steiner. Reitzas explained that during these sessions they recorded the orchestra and the rhythm section at the same time, through the desk, using a combination of close and ambient mics. Of course, it made sense to wait until the demo arrangements were 100-percent finished before embarking on costly orchestra sessions — but when working with Streisand, you can never say you’re finished...

“Everything can be turned upside down on a Barbra record at any moment,” explained Reitzas. “She will have finished her vocal, and by the time you start or even finish a mix she might say: ‘You know what, I want to go back to a version that I did three weeks ago.’ Or she’ll suddenly want to add a new interpretation of a dialogue line. I take pride in being able to do those things, and quickly. I’ve worked with Barbra for nearly 25 years, and she has taught me so much about making records. She has been singing, acting, directing, and producing for six decades, so there is a lot to learn from her. Many years ago I said to her, in a humble sort of way that ‘if you can imagine it, I can do it.’ Knock on wood, this has worked so far. I think the longevity of our working relationship stems from the willingness to meet her ideas head on. She has some of the most creative, sometimes crazy requests, and people before me would tell her: ‘No, you can’t do that.’ I learned very early on that you don’t tell Barbra that you can’t do something, because if she has a feeling or an idea or thinks that something can be done in a different way, then it is possible, even if it might take a lot of creative ‘outside the box’ thinking or studio magic. McDSP’s Revolver was used to create a ‘PA’ effect on Bradley Cooper’s dialogue track.

McDSP’s Revolver was used to create a ‘PA’ effect on Bradley Cooper’s dialogue track.

“For example, there were a couple of times where she had a vocal idea that she had recorded into her iPhone. I would put these ideas in the session as markers so we could later record those ideas properly on her microphone, but when we later tried to re-record some of those ideas, she was like: ‘No, I like my reading of what I did on the iPhone better, so let’s just use that.’ So you have to make it work. There are different techniques that you can apply. Obviously you use things like EQ and compression, or maybe you put a cymbal roll right before or after to try to trick the ear into not noticing or focusing on the sonic differences of the part I am trying to keep in there from the phone recording.

“Another example was dealing with the spoken word of Bradley Cooper, who played the part of the director in ‘At The Ballet’. We had tried Walter and then her husband speaking the part. Then Barbra had a great idea to see if Bradley Cooper wanted to give it a try, and at the very last minute, after I had practically mixed the song, she contacted Bradley Cooper. He recorded his voice on his iPhone and sent that to us. The director’s part in this song has to sound as if he’s speaking via a PA from the middle of the audience seats to the actors on stage, so actually the low-quality iPhone recording ended up working fine. I used McDSP’s Revolver plug-in for the PA effect and Barbra loved it. As an example of the ever-changing arrangements, after we had inserted Bradley’s lines into the song, Barbra felt the flow of the piece a little bit differently, so we had to change the tempo of the orchestra in a few spots and go back to one of the earlier orchestra takes to find some chords that were a little bit longer to replace what was there, to give it the feel that Barbra heard in her head.”

The ‘A’ team behind Barbra Streisand’s Encore. From left: producer and arranger Walter Afanasieff, arranger William Ross, David Reitzas, drummer Vinnie Colaiuta and guitarist Dean Parks.

The ‘A’ team behind Barbra Streisand’s Encore. From left: producer and arranger Walter Afanasieff, arranger William Ross, David Reitzas, drummer Vinnie Colaiuta and guitarist Dean Parks.

The Style Edit

Reitzas didn’t only repeatedly edit instrumental sections in sometimes great detail, but also prides himself on his vocal editing. “I have a long history of working on vocals and helping artists deliver great vocal performances. This started in the ’80s on analogue tape by the side of David Foster, and exploded in the early ’90s when I began using the Sony 3348 [digital 48-track tape machine], which almost literally made my career, because of what the built-in sampler allowed me to do. The things David and I had done with the AMS 1580 — loading stuff into it from analogue tape, treating it, and then flying it back onto tape — I could do internally with the 3348’s on-board stereo sampler, but much faster and with more accuracy. I read the manual in every spare moment that I had, and also figured out how to do things that were not in the manual. I was able to grab things with the sampler, and fly around vocals and move them where needed, punch them in with crossfades, or lay back a vocal 10-15ms if it felt a little rushed, and so on. I even replaced drums with samples using an external trigger. I could digitally improve an artist’s vocals even before they knew it could be done, way before Pro Tools or Auto-Tune were in the picture. Artists like Madonna, Whitney Houston and Céline Dion were just a few that fell in love with my abilities to do that, and it’s also how I strengthened my relationship with Barbra. Also, working side by side with Walter Afanasieff over the past 20 years has taught me an abundance of record-making knowledge. He’s a genius!”

The Encore album featured a stellar array of Hollywood talent: Hugh Jackman poses between Walter Afanasieff (left) and David Reitzas. Obviously, working with Pro Tools has made these things even easier to do for Reitzas, although he asserts that the DAW is a double-edged sword, enabling an unwillingness to commit that is characteristic of the modern recording process. “For example, in the past, I would record a full, 80-piece orchestra on 15 tracks at the most, even if I had more than 50 microphones. But today it’s one microphone per track. In the old days you just kept recording until it was right, and you didn’t do as much fixing. Now you do tons of different takes, and end up with layers and layers of multiple takes, sometimes running into track counts in the thousands on these orchestral sessions. It takes a lot of time and patience these days to sort through everything and create a final take in a more manageable session.”

The Encore album featured a stellar array of Hollywood talent: Hugh Jackman poses between Walter Afanasieff (left) and David Reitzas. Obviously, working with Pro Tools has made these things even easier to do for Reitzas, although he asserts that the DAW is a double-edged sword, enabling an unwillingness to commit that is characteristic of the modern recording process. “For example, in the past, I would record a full, 80-piece orchestra on 15 tracks at the most, even if I had more than 50 microphones. But today it’s one microphone per track. In the old days you just kept recording until it was right, and you didn’t do as much fixing. Now you do tons of different takes, and end up with layers and layers of multiple takes, sometimes running into track counts in the thousands on these orchestral sessions. It takes a lot of time and patience these days to sort through everything and create a final take in a more manageable session.”

Many engineers make notes to help keep track of what’s what, but — amazingly — Reitzas prefers to keep it all in his head. “I don’t take tons of notes. Instead, I remember. I have an assistant at the studio, but when I work with [Streisand] at her house or when I am working at my house on my own, I have to have a good memory. I come from the old school of making records on tape where you had to visualise everything that was recorded on the tape. No looking at waveforms or grids. I try to apply that same visualisation technique even when using a DAW. With Encore we were in a situation where Walter was busy at his place doing demos, Bill Ross was doing demos at his studio, and I was working with Barbra, and also coordinating the different camps. To collect all the different changes that were emailed to us throughout the day, every day, and keep everything organised and maintain a clear vision in my head of what was what was a monumental task. I continuously need to keep track of all the changes that we are making with the possibility that things might change at any moment.”

Mixes: The Rough & The Smooth

Ever since the recordings started in earnest in February, Reitzas had not only been recording, editing, comping, and whatnot, but also making rough mixes, working entirely in the box. At the end of May and early June, with all the material recorded, or so he thought, Reitzas went to his favourite hide-out, Westlake Studio E in Hollywood, and mixed 13 songs over the course of six days. However, these mixes were once again just another phase in an ever-changing process, because they were not intended as the final mixes. Reitzas had by now whittled down all 13 sessions to approximately 192 tracks each, but needed to get these sessions down to more concise and manageable sessions before going out to tweak the final mixes with Streisand. For each song, he sent the instruments in the session through the studio’s 72-input SSL 9072 J Series desk to condense them to 40-50 stereo stem tracks.

“I’d like to stress that I don’t consider myself a mixer, although I do mix records,” says Reitzas. “Instead I think that my greatest talent is to be a record-maker for the artist. I’ve long had the opportunity to lock out a room and just become a mixer, but I have always shied away from that, because to me the most valuable thing is when you sit with an artist making a record, and you get to see what they like and don’t like. All the information that I gather while recording helps me to mix a record. With Barbra, from the first note we record to the very end, I am gathering information to help me make decisions in the mix. Without that information I can still mix, but it is not as satisfying to me, because I like mixing through the mind of my artist. Once in a while I get lucky, like with the song I mixed for the Weeknd, ‘Earned It’, which was a quick one-day mix, in which I did not really have much time to really think about it or spend any time learning from the artist. It was a matter of just doing it and making it feel great, using gut instinct. That is something that I can look at and be proud of.”

David Reitzas and Barbra Streisand share the Tonight show couch.Another Reitzas quick mix that did more than OK was Whitney Houston’s 1992 super-hit ‘I Will Always Love You’, which became the seventh best-selling single of all time, selling 20 million copies worldwide. In his autobiography, Hit Man, David Foster describes how he asked Reitzas to do a “passable rough mix” to show the record company what they were up to, and how, despite Foster’s protestations, Arista’s Clive Davis insisted on releasing Reitzas’s rough.

David Reitzas and Barbra Streisand share the Tonight show couch.Another Reitzas quick mix that did more than OK was Whitney Houston’s 1992 super-hit ‘I Will Always Love You’, which became the seventh best-selling single of all time, selling 20 million copies worldwide. In his autobiography, Hit Man, David Foster describes how he asked Reitzas to do a “passable rough mix” to show the record company what they were up to, and how, despite Foster’s protestations, Arista’s Clive Davis insisted on releasing Reitzas’s rough.

“If one of my rough mixes ends up being really good, it usually is when I am not using my brain that much, so it is all coming from the heart and from instinct, and I am not thinking: ‘Oh, this is going to be a final mix.’ I like to keep things spontaneous and instinctive in general, and for this reason I don’t use templates when I record or mix. When I start up a session, I always open up brand-new plug-ins for each track depending on what my instinct thinks could improve the sound, including reverbs. I’ll build from zero, and similarly, although there are some things that I gravitate towards in mixing, I treat every mix as a brand-new entity.

“The reason is that I want people to feel something new when they are hearing a song that I mixed. Of course I want to make it sound great, but I also want to almost take the listener’s hand and walk them through the mix and say: ‘Listen to this, and then listen to this, and then listen to that.’ I am building an emotional path for the listener to follow. At the same time I also want there to be enough clarity in the mix for the listener to have the luxury of listening to any other part of the song. That is how I approach my mixing, and it is universal for every genre of music that I work on.

“Because of my focus on feeling and performance while mixing, I still like to mix on a desk. When using a desk I actually mix with my eyes closed 90 percent of the time, because when you’re looking at a screen, you may get things technically right as you’re punching in numbers, but I prefer to have everything at my fingertips and to play and feel the mix to where I want it to be. I may have an idea and reach over to execute it with one hand while I’m doing something else with my other hand. On a console I’m mixing in real time, with instant feedback from my touches. It’s not a matter of: make a change, go back, listen to it, save, listen again.

“I try to get my mixes to sound really good on a console, first without automation, and then the real magic happens when I start to ride the dynamics of a song on the faders. I use a lot of automation: in the box before the session hits the console, on the console, and again with the 50-track stem session for the final two-mix with Barbra. But I get the most bang-for-the-buck automation from the console because I’m touching the faders and using the console as an instrument.”

Mixing At Grandma’s

The final stem-mixing process, with Reitzas mixing these 50-odd tracks and the vocals in the box down to stereo, took place in a rather more unusual environment. “In the case of Barbra’s records, when I’m working on the console I know I’m not doing the final mix, because I still have to go to her place, which she calls Grandma’s House, and together with her I’ll mix down the vocals and the 40 or 50 stems that I have printed. I do this final mix just in a room at her house, without any acoustic treatments, with one speaker half-hidden behind a piano, so I don’t really get that sitting-between-the-speakers vibe.”

As you can see in the photo, mixing at Grandma’s House takes place in an ordinary wood-panelled sitting room, with David Reitzas’ laptop sitting on a low table on wheels, not even close to the sweet spot between the two monitor speakers. When mixing Partners there, Reitzas used Streisand’s two white-grilled Genelec 1031s, but for Encore he replaced them with his own Genelec 8351s. But why make his life so difficult?

“At one stage in 2002, I was mixing a record at a studio in LA and she would listen to my mixes in Grandma’s House in real time through EdNet [ISDN lines to the house]. She kept saying that there was too much reverb, and I was puzzled because it sounded OK to me. I kept making the mix dryer and she kept complaining about the reverb. When I went to her house the next day, I noticed that the sound was coming through a Sony receiver that allowed you to add your own reverb, which someone had accidentally set to add extra reverb. So she wasn’t hearing things accurately. A similar thing happened with her listening to the small stereo in her bathroom and saying that the mix had too much bass. Again, it had accidentally been set to boost the bass. I realised that I needed to know what she was actually listening to, and so in 2002 I decided to take the plunge and mix everything down to stems and then go to her house to mix these stems using Pro Tools, with her sitting by my side.”

David Reitzas’s impromptu mixing setup at ‘Grandma’s House’: not a controlled acoustic environment!

David Reitzas’s impromptu mixing setup at ‘Grandma’s House’: not a controlled acoustic environment!

Reitzas adds that it was at the same point that he switched from using the 3348 to Pro Tools, because it obviously was not practical to regularly wheel a huge tape recorder and desk in and out of Streisand’s house. “When I mix down to 50-odd stem tracks at Westlake, I get the mix sounding really good, in the process using my outboard gear and also finally adding quite a few plug-ins. I know the mix has gone though a good console, good outboard, and I’ve heard it in an acoustically treated room with good speakers. So when I open up that stem session at Barbra’s, I know that no matter how it sounds there, it sounds right in the studio. Even though we’re finalising in a non-studio environment, I trust that the elements that I am working with are right. Also, because Barbra and I have been working in that room for many years, we know what it should sound like there. Plus, we always make CD references to listen to in other places and in the car.

“Besides just my Pro Tools setup, I also take some outboard with me to Barbra’s, like my Bricasti M7, Tube-Tech CL1B compressor, my NTI EQ3s or Mäag EQ4s, and my Audio-Technica headphones. She sits to my right, and occasionally I’ll move to the middle, where she normally sits, so I can get the in-between-the-speakers vibe. It’s pretty cool to work on her records in this space, and the food is the best ever! If you can make it sound good there, then you can make it sound good anywhere. It’s like David Foster was saying: you have to do the best with what you have.

“Also, there’s one more stage after Barbra and I do the final mixes at her house, which is mastering. I did the mastering with Adam Ayan at Gateway Mastering in Maine, and was there with my laptop with the stem sessions ready to make any necessary changes. We listen intently, taking notes on what we think can improve the sound of the record. If we find that the bass levels need adjustment, or we feel a vocal needs to come up a bit, instead of EQ’ing the stereo mix, I go back into the stems and bring the bass down there or make the change to the vocal. I’m mastering at Barbra’s insistence, because this is our last chance to get everything just the way she wants.”

'At The Ballet'

‘At The Ballet’, a track from the 1985 musical A Chorus Line, is both Encore’s opener and first single. At seven and a half minutes, it is by far the longest song on the album, and the only one that features three vocalists: in addition to Streisand, also Anne Hathaway and the very British-sounding actress Daisy Ridley, known for playing Rey in Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

In addition, adds Reitzas, “’At The Ballet’ was the only song that I mixed at Westlake and didn’t tweak at Barbra’s house with her, because it was released more than two months before the album, as a teaser track. I still went through the process of mixing through the console to stems, but we communicated over the phone and through email on making any changes she wanted before signing off on the mix. The other odd thing about that track was that because the dialogue is about three dancers auditioning on stage for a Broadway play, Barbra wanted it to sound like a rehearsal band playing in an orchestra pit. That was quite a challenge for me, because I had to make it sound as if it were performed by a Broadway rehearsal band and not by the best session musicians — but we had Vinnie Colaiuta on drums, Chuck Berghofer on bass and Dean Parks on guitar, recorded in a world-class LA recording studio! So in that sense, the mix was intentionally made not to sound too polished, and I purposely did much less fancy processing on Vinnie’s drums than I would have done on any other song.”

The Condensed Version

In other respects, Reitzas’s mix process for ‘At The Ballet’ was pretty much the same as that for the other songs. As described above, he edited and condensed thousands of recorded tracks — which included takes of the three vocalists talking and singing, the orchestral and band recordings and the demo recordings — to about 192 tracks, which he then mixed to both a stereo reference mix and to his usual 50-odd track stem session. After receiving feedback, he made his mix tweaks using the latter.

You might ask whether using a console complicates the entire mix process, given that the mixes start and end in the box. “Using the desk is also about the sonics,” replies Reitzas, “and with that the gear that I use, ie. the console and my outboard, in particular the reverbs. For example, my Bricasti M7 is my go-to reverb: it is the most beautiful, most natural reverb that I use. The outboard I used on the mix of ‘At The Ballet’ included the SPL Vitalizer, the SPL Stereo Q, and the Spatializer Retro on the orchestra; the NTI EQ and the dbx 160X compressor on the piano, the GML EQ on the woodwinds, a Summit EQ on the horns, a Tube-Tech EQPE1C on the bass, and my Mäag EQ2 on the guitar. Nothing too fancy, and very little if any compression on most sounds, since my dynamics come from automation. As things go through the console and I feel something needs a touch of EQ, I just use the console.

“Most of my ambience comes from the Bricasti, an AMS reverb, or my Eventide DSP4000. I also have a TC M5000 that I used a little bit for some deeper ambience. To bring the drums out on other songs I usually put them through the SPL Transient Designer. I print the stems one by one back into the same Pro Tools session, going through my SPL Passeq EQ and my SPL Iron Compressor. Every stem goes through that chain.

“The vocals don’t go through the console, because they can change at any minute. We could be ready for mastering, and Barbra might have an idea for a different melody or spoken-word line, so I need to be able to at any moment replace or add a vocal part that fits with the other vocals in the box. In the case of ‘At The Ballet’ I also didn’t steer the drums through the desk, because I wanted them to sound raw. After I’ve recorded all the stems back into the session, I will clean up the session, hiding all the original tracks, spreading out my stems, and I’ll leave the vocals, and in the case of ‘At The Ballet’ the drums, as they were.”

Sends & Sensibility

David Reitzas’s Pro Tools sessions are clearly laid out and named. The 192 track pre-mix session of ‘At The Ballet’ has a Master FX track at the top, followed by his rough stereo mix track, and then a series of aux tracks for strings, woodwinds, horns, percussion, piano, drums, more percussion, guitar and bass. The aux tracks are, said Reitzas, to allow him “to make quick adjustments to entire instrument tracks, instead of VCA tracks”. Below the aux tracks are the vocal tracks, a trumpet aux, three tracks for the orchestra tune-up and people chatting noise at the beginning, temporary reverb tracks from the AIR Reverb and UAD EMT 250 reverb, and a Bricasti M7 reverb print track for each vocal. Below this are all the instrumental tracks, starting with orchestra ambient, strings, violas, celli, basses, woodwinds, horns, percussion, drums, piano, synth celeste, acoustic bass and electric guitar.

The full Pro Tools session for ‘At The Ballet’.

The full Pro Tools session for ‘At The Ballet’.

The stem session is, naturally, far more simple, and consists of, from top to bottom: master effects, final mix, an ‘All Music’ VCA and an ‘All Vocals’ VCA, aux tracks each for Streisand, Hathaway and Ridley, a lead audio track for each of the three singers, four background vocal tracks, a Bricasti track for each of the singers, a Bradley Cooper aux track and three audio tracks for him. Below this are the stem tracks: strings, woodwinds, horns — each with a double called Synth, from the original demo version — harp, percussion, piano, harpsichord, acoustic bass, electric guitar, synth harp, timpani, ‘Walla’ (the ambient noises at the beginning of the track), and then drums, as separate tracks, and finally Reitzas’s two temporary reverb tracks.

The striking thing about both the premix and the stem session is how few plug-ins there are. His 192-premix session for ‘At The Ballet’ has a ‘D’ send on only 14 of the instruments, all coming from the demo, which goes to an aux effects track with the Avid AIR Reverb, while the snare top has a send to an aux track with the UAD EMT 250 reverb. There’s also a Waves Renaissance Bass on an insert of the acoustic bass track, and, er, that’s it — on 150-odd tracks.

The three singers are also very minimally treated, with the Avid EQ1 high-pass filter, Waves Renaissance Vox and Renaissance Compressor on each of them, and an additional EQ7 on Streisand’s vocal. Bradley Cooper’s aux track has the aforementioned McDSP Revolver, as well as a Waves Renaissance Axx. The strings, woodwinds and horns auxes also have a send to the AIR Reverb, and the piano, drums, and guitar auxes have a send to the EMT effect aux. The Master FX track has the Brainworx BX_hybrid equaliser, and that’s it.

Fancy Trim

The stem session has a little more processing, but a grand total of 36 plug-ins on the inserts of a 50-track session is still pretty minimal, especially as 15 of them are on the three vocalists. Reitzas highlights a few of the more important plug-ins: “Although each of the singers has the same vocal chain — McDSP FilterBank, Mäag EQ4, Waves Renaissance Vox, UAD LA2, UAD Precision De-esser — that chain is actually unique to this session. The McDSP FilterBank gets rid of low-end rumble on all three vocals. On Barbra’s vocals the Mäag EQ4 adds some 2.5kHz to help it cut through and 10kHz for some air. It’s my go-to EQ, as it has five bands plus an ‘air’ band of really musical frequencies. I like using the Renaissance Vox on vocals, but I don’t normally use the LA2. Here it’s doing just 1dB of compression, which made me feel good. The de-esser is working very subtly. These plug-ins would have different settings on each of the vocal tracks. The vocals also still have the send to my temporary AIR Reverb, and below the vocals you can see three Bricasti M7 print tracks, one for each vocal.

The Mäag EQ4 plug-in formed a part of David Reitzas’ signal chain on all the sung vocal tracks.

The Mäag EQ4 plug-in formed a part of David Reitzas’ signal chain on all the sung vocal tracks. Relatively few plug-ins were used in the eventual mix, among them McDSP’s 6030 Ultimate Compressor on the acoustic bass.“In addition, the Percussion stem has a Renaissance Axx, which I like to use if I want some more ‘oomph’ or more level. I will put the attack as slow as it goes, and I’ll then move the threshold to get a little bit more gain out of something without changing my automation. I guess you could say it is a fancy trim knob. The acoustic bass stem has the Waves Renaissance Bass, and the ‘6’ send is a McDSP 6030 Ultimate Compressor. The harpsichord stem has a Renaissance Axx. There are again various ‘D’ sends, once again going to my temporary AIR reverb, which I probably ended up using.

Relatively few plug-ins were used in the eventual mix, among them McDSP’s 6030 Ultimate Compressor on the acoustic bass.“In addition, the Percussion stem has a Renaissance Axx, which I like to use if I want some more ‘oomph’ or more level. I will put the attack as slow as it goes, and I’ll then move the threshold to get a little bit more gain out of something without changing my automation. I guess you could say it is a fancy trim knob. The acoustic bass stem has the Waves Renaissance Bass, and the ‘6’ send is a McDSP 6030 Ultimate Compressor. The harpsichord stem has a Renaissance Axx. There are again various ‘D’ sends, once again going to my temporary AIR reverb, which I probably ended up using.

“The drum aux has the UAD Studer A800, and the ‘5’ send again goes to the EMT effect aux. I rolled off a little bit of the low-end on the kick with the FilterBank, the snare top has the Mäag EQ4, and the hat has the Massenburg MDWEQ5, boosting at 7kHz.

"Finally, my Master FX track at the top has my stereo chain, which consisted of the Brainworx BX_hybrid, and iZotope’s Ozone 7, and the stereo mix gets printed on the track below. It’s nice if your record is loud and competitive with other records, but in general I don’t like to use compression a lot. I try to get as much level as I can using the dynamics in the mix, ie. pushing faders and carefully massing volume rides.”

The Ozone 7 mastering plug-in from iZotope took care of stereo bus processing duties.

The Ozone 7 mastering plug-in from iZotope took care of stereo bus processing duties.

Becoming The Perfect Engineer

“I’ll tell you a funny story,” says David Reitzas. “After I’d worked on some hit albums with David Foster, he was in the middle of a divorce and we had to quickly move out of the beautiful studio in his house, which had a big console, marble floors, acoustically treated rooms, and so on. Instead we moved into a garage with sheet rock and drywall, no sound treatment, and no air conditioning. One day the gardener was outside with his leafblower and there were mosquitos flying around the room. I started to get bitchy and complained to David, ‘How are we supposed to make a great record in these conditions?’ He looked me straight in the eye and said: ‘Listen, I don’t need you to complain. If you can’t make the best in any given situation, then I don’t want you here.’ It hit me like a brick, and I immediately understood: this is why this guy is who he is. If you can’t do the best with what you have, you won’t get anywhere.”

The comment galvanised Reitzas in his pursuit of perfection. “We all strive for perfection, but what I’ve learned is that from a musical perspective, perfection does not mean things being perfect according to a grid or a frequency. It’s about getting the perfect performance, even if it is a little shaky, or a little bit out of tune. The most important thing is recognising when something is the best that it can be. David [Foster] has a great talent for that. Somebody might sing a verse, and 95 percent of it would be pretty bad, but if there was five percent that was magical he recognised it right away, and that is what he focused on, and he would encourage the singer to give more of that.

“David has such a great sense of music, and personal skills, and work ethic. He also taught me a lot about timing and pitch. I remember a moment during the first couple of months when we were working together, and we were tuning a vocal with an AMS DMX 1580. He was knocking it up a few cents here and there, and I couldn’t hear any difference with what he was doing. But now, after having spent so many years in the studio and training myself, I can hear how timing increments in milliseconds and pitch increments in cents can make a world of difference in how a performance evokes a different emotional response.

“But once again, it’s not about what’s perfect from a technical point of view, it’s about what feels good. I have been fortunate to work with studio royalty, and I recall sitting in a room with Phil Ramone on one side and David on the other side, and I got to witness how great people can hear things completely different. One person might say that a take is a little too late, and the other might say that it felt a little early or rushed. Spending time with Mutt Lange also was a lesson in feel, focusing all the time on what would bring out the most emotion in the listener, on how to move the listener.”

While musical performances are all about feel, from an engineering perspective, technical perfection is a priority. Reitzas takes “a lot of pride in not making mistakes. When I made a mistake in my younger days, I’d go home at night and I would not go to sleep until I had figured out why I had made that mistake, what I could have done better, how I could have been more prepared, and I would learn my lesson. And then I would make another mistake, and I would do the same thing. I still take full responsibility for everything that happens on my watch. For example, when I am printing mixes or stems I don’t turn it over to an assistant who could overlook something, and I make sure everything is printed right, labeled right, emailed properly, and so on.

“Particularly when you are mixing, you spend all your time fixing things that aren’t right. You’re improving things that aren’t the way you want them to be, trying to get closer to the vision of the artist. You are making things better bit by bit. All this takes a lot of patience, a lot of preparation, and a lot of pride in your work. Perhaps I have to add personality to that, meaning that you have to have the right attitude. Sometimes there are difficult moments in the making of a record. An artist might get frustrated and you have to develop a thick skin and not take it personal, so you can still focus on giving the artist what he or she wants.”

Demons In The Demos

“The demos that arrangers and composers are now able to create make our lives easier and more difficult at the same time,” opines David Reitzas. “We used to spend a lot of time working out the arrangements, the dynamics, the speeding up and slowing down, key changes, tempos, pauses, while recording the orchestra. But now we start with the demos, and then a lot of technical stuff goes into adding real musicians to these demos, and making it sound like everything just came together naturally. It can become a very technical exercise for me, but the main vision that supersedes everything is to make it sound beautiful and real.

“Because Walter’s demos are so good, I often end up keeping both the live orchestra and rhythm section recordings as well as the demo sounds in the final mix. However, during the recordings for Encore the players were not listening to the demo parts. Instead Bill Ross conducted the orchestra using movie streamers to keep in time with the score, rather than using a click. This means that I later have to go in and line up the demo sounds to the real players, or vice versa. Also, because Walter’s orchestral mock-ups are so good, Barbra often asked why we needed to replace them with a real orchestra. Actually, on one of the songs, ‘Anything You Can Do’, we did use the demo as the final. We had a session booked with real musicians, but we ended up keeping the demo because it just sounded so good. I did an early rough mix of the demo of ‘Anything You Can Do’, with real horns arranged and played by Chris Walden, and when Barbra and Jay heard it, they said: ‘Cancel the session!’”

Never Finished

David Reitzas constantly adjusted his mixes in response to feedback from Barbra Streisand, to the point where he was even receiving mix notes from the singer three weeks after Encore’s release! “Barbra is still listening to the album a lot because Sirius XM created a Barbra Streisand channel for the month of September. Unfortunately, Sirius Radio sounds pretty dreadful compared to the high-quality masters that she worked so hard on. She’ll listen to the CD in the car and love it, then she’ll hear a song on Sirius and she hates the way it sounds. So it’s important for her to let me know how she’s reacting to our work and to create a reference point for next time, when she can say, ‘Remember the last time how the orchestra was too low through the satellite radio, so this time let’s raise the orchestra to compensate.’”