Brush up on your listening skills, as we dissect some hits from a recording and production perspective.

Portugal The Man

There’s so much to enjoy in this inventive production, but I particularly like the effects use. The crusty mono reverb (a spring, I’d hazard) with its clear 16th‑note predelay, nicely offsets the eighth‑note delay spin on “hah!”, and you can hear how filtering in the latter’s feedback path gradually emphasises the mid‑range of the trailing echoes. Then the lead vocal’s echo treatment gives the right channel a significantly longer delay time, adding a cool rightwards ‘swerve’ to the tails of exposed words right up until the end of the first chorus. Unusually, though, this effect is pulled well down in the mix from then on, which serves to freshen up the second verse a little to my ear, as well as drawing less attention away from the lovely little space‑invader SFX at 0:49 and the entertainingly modulated synth pad that slinks in not long after. But my favourite is what sounds like a deeply phased and/or formant‑modulated backing‑vocal texture at 1:25 and 1:37, and the similar effect on the middle section’s “Is it coming?” refrain. Oh, and the dynamic panning before the final choruses. Who says I can’t have two favourites? Mike Senior

Lost Frequencies & Zonderling

It’s the construction of the main melody line that intrigues me most in this song. First of all, I love the tricks it plays with your expectations. The verse’s third line, for example, begins by following the basic rhythmic template of the previous two but drops the downbeat at 0:22, not only drawing attention to the nicely melismatic variation on “gone”, but also subliminally underpinning its lyrical content. Though that moment repeats through the song, we’re not allowed to get too used to it, with the second verse adding in a supporting ambient backing‑choir layer and then warping the end of the melodic contour with the final statement at 1:46. I also like the way the line strives further upwards for “let me be the one to set them free” at 0:26 — almost like a statement of intent, given that this idea is retained for the opening of the second verse before the whole line shifts up in register at 1:32. In a similar vein, it’s curiously satisfying that the verse’s opening “oh lord” prefix and the chorus’s “crazy” suffix share the same rhythmic identity, as if the verse’s rising line is posing a question to which the hook provides the answer.

The end‑of‑chorus phrase extension places a nice extra stress on the title lyric (helped by the sudden arrangement drop‑out), and it’s cool how it’s derived by transposing the “whatever they/you want” melodic scale fragment downwards for “so what if I am”. Again, there seems to be an echo of this technique in the second verse, where the scale of “every part of me” is followed by a cascade of two lower‑register scales on “put my heart where everyone can” (1:43). Regardless of whether the songwriters applied these kinds of structural devices consciously (I can only speculate), they’re part of what makes this song so effective; I hear plenty of project‑studio productions that would do well to take some of these ideas on board. Mike Senior

Calvin Harris & Dua Lipa

One of the interesting things about tuning is that it’s not solely a musical issue; it also affects the way sounds blend. When something’s bang in tune with its musical backing, it actually coheres better with the mix. This is, I suspect, one reason why pop vocal tuning is often so assertive; it allows you to maximise lead vocal levels without dislocating the singer from the rest of the production. Producers rarely make much use of the opposite tactic (getting something to stand out of the mix by detuning it) but there’s a great example here, where the brass‑like sound first heard at 1:11 sounds as though it’s been pitch‑modulated in some way, and really grabs the ear as a result, despite its fairly modest mix level — a definite bonus for EDM productions where you usually want to give the drums and bass as much mix headroom as you can muster.

There’s also a fun arrangement trick at 2:57, where the culmination of the middle section’s slow textural build‑up isn’t the full chorus texture you might be expecting, nor even some kind of stripped‑back ‘rhythm and vox’ breakdown, but instead just the vocal on its own for “one kiss is all it”. This is already quite a startling move, almost to the point where it feels momentarily as if we might have arrived at the song’s tail‑out line, but then the full backing rather disconcertingly returns without any warning on the back‑beat of “takes”. It’s two surprises for the price of one! Mike Senior

Jay‑Z

The stark introduction of this double Grammy‑nominated hip‑hop production makes arresting use of abrupt looping on its underlying sample (a deeply cool soul cover of ‘Late Nights & Heartbreak’ by Hannah Williams & the Affirmations). Far from being some kind of throwaway gimmick, this foreshadows the essentially unsettling character of the musical structure in the main body of the song.

For a start, the song’s most frequently recurring musical section (first heard at 0:26‑0:42) is six bars long, but it’s constructed from a four‑bar section of the sampled track by looping the third bar three times. I doff my cap to the track’s producer No ID for this simple, yet radical, production stunt, because it’s at once something that almost everyone would instinctively have shied away from, and something that I think powerfully underlines the painful awkwardness and vulnerability Jay‑Z is projecting in these rhymes. It’s also great how, once we’ve had three of these six‑bar units, the following six‑bar unit (which doesn’t include any loops at all) slows down slightly towards its close, but without the section duration getting any longer, so the return of the main six‑bar section feels like it comes in a bit too early — again, a fabulously discomfiting effect which is totally in keeping with the emotional message, in my view.

On top of that, Jay‑Z’s raps don’t neatly follow the music’s 4x6‑bar ‘A‑A‑A‑B’ structure, which lends a stream‑of‑consciousness authenticity to his extended lyrical mea culpa, as well as contextualising a couple of key moments (“you matured faster than me, I wasn’t ready, so I apologise” at 1:25 and “if my children knew, I don’t even know what I would do” at 3:34) as more introspective by virtue of their coinciding with ‘B’ section’s beat‑less ritenuto tail. All in all, this is a production with real depth, and a shining example of how much artistic value sample‑based musicians can generate over and above the musical content of the sampled building blocks they work with. Oh, and I for one will definitely be adding that Hannah Williams & the Affirmations album to my shopping list... Mike Senior

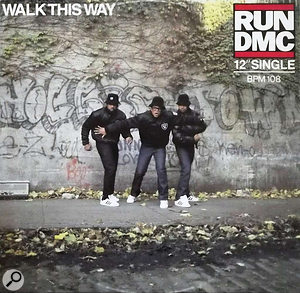

Classic Mix: Run‑DMC ‘Walk This Way’ (1986)

A pioneering collaboration between Run‑DMC and Aerosmith under the auspices of production guru Rick Rubin, this not only catapulted the rap‑rock sub‑genre into the mainstream, but also helped launch the career of one of the all‑time great mix engineers, Andy Wallace. Despite the heavy gated (or sample‑triggered?) snare ambience, what impresses me is how aggressive and upfront this production sounds. That might seem nothing special these days, when we’re so used to super‑dry and present mixes, but in 1986 Rocky IV, Karate Kid II and Top Gun had saturated the airwaves with lushly reverb‑tastic offerings like Survivor’s ‘Burning Heart’, Peter Cetera’s ‘The Glory Of Love’, and Berlin’s ‘Take My Breath Away’. In that context, ‘Walk This Way’ must have felt like a bolt from the blue!

A pioneering collaboration between Run‑DMC and Aerosmith under the auspices of production guru Rick Rubin, this not only catapulted the rap‑rock sub‑genre into the mainstream, but also helped launch the career of one of the all‑time great mix engineers, Andy Wallace. Despite the heavy gated (or sample‑triggered?) snare ambience, what impresses me is how aggressive and upfront this production sounds. That might seem nothing special these days, when we’re so used to super‑dry and present mixes, but in 1986 Rocky IV, Karate Kid II and Top Gun had saturated the airwaves with lushly reverb‑tastic offerings like Survivor’s ‘Burning Heart’, Peter Cetera’s ‘The Glory Of Love’, and Berlin’s ‘Take My Breath Away’. In that context, ‘Walk This Way’ must have felt like a bolt from the blue!

It’s also easy to underestimate the production’s complexity. Yes, there are plenty of big, bold elements in there: the merciless sampled drums, the guitar riffs and the alternation between Run‑DMC’s rapped verses and Steven Tyler’s sung choruses. But the closer you listen, the more nuances emerge. For instance, this production might appear to have no bass part (and the strong ‘C’ pitch to the kick sample potentially obviates the need much of the time), but there’s something sneakily sidling in at 0:26 to underpin the first verse. It can also be detected in the choruses, where its rhythm deviates from that of the guitar. (If you can’t hear what I’m talking about, low‑pass filter the mix at 100Hz and it’ll become more clearly audible.)

The way the verse is developed throughout the production is cool. The second verse, for instance, adds live ride‑cymbal overdubs, a lead‑guitar fill at 1:02, and Tyler’s pitched call‑and‑response contributions on phrases such as “kitty in the middle” (1:00) and “ready to play” (1:06). Then, after the third verse has stripped things back to a loop from Aerosmith’s original 1975 release (a nice touch!), Tyler joins the rapper in an equal lead role all through verse four. In fact, despite strong competition from the samples, riffs and raps, Tyler totally steals the show with his hook line. Not only is it extraordinarily high (high Bb and the Eb above it), but the tone is so gloriously filthy and distorted that it merges seamlessly with the guitar timbre to create something more than the sum of its parts. So striking is this timbre, in fact, that I don’t feel in the least short‑changed despite there being, unusually, only two such hook sections in the entire song. Mike Senior