Screen 1. Frequency 2 combines powerful EQ and dynamics control in a single processor.

Screen 1. Frequency 2 combines powerful EQ and dynamics control in a single processor.

In Frequency 2, Cubase 11 Pro has a powerful dynamic EQ.

Version 11 of Cubase Pro added dynamic functionality to the already excellent bundled Frequency EQ plug‑in, and in this workshop I’ll take you through some examples that demonstrate what you might look to achieve with it in your mixes. If you’ve not yet upgraded to v11, or aren’t a Pro version user, don’t worry: you can still follow the examples using a freebie dynamic EQ such as Tokyo Dawn Labs Nova and perhaps upgrade later. You’ll also find some accompanying audio examples on the SOS website: https://sosm.ag/cubase-0921 or download the ZIP file below.

Control Freq

Let’s start with a simple example: an acoustic guitar track, whose lower‑mids we wish to ensure don’t get out of control. In Screen 1 above, I’ve toggled on Frequency 2’s SING (single‑band) view, so all controls for the selected band are visible. I’ve selected a Peak filter and, in the EQ section (on the left), applied a 12dB cut at 200Hz, with a Q (which dictates how wide the filter is) of 2. I’ve left the band in the default Stereo processing mode; there are also Left/Right and Mid/Sides options, but I’ll cover them another time.

Such EQ settings ought to remove some lower‑mid mud but a traditional static EQ cut also risks leaving the guitar sounding thin when the arrangement leaves it more exposed. By making this EQ band dynamic we can avoid that unwanted side effect. To do so, enable the Dynamics section in the middle, which will automatically enable the Side‑chain section in Internal mode and with Auto engaged. For reasons that will become clear, this is a good starting point generally and ideal for this example.

The Dynamics section offers the user a typical compressor’s control set (Threshold, Ratio, Attack and Release) alongside a less familiar Start knob. Leaving Start at 0dB for now, the Ratio control will influence the amount of gain reduction, lowering the Threshold will then eventually make some gain reduction occur, and the speed of the compressor’s response can be adjusted using the Attack and Release controls.

There are three key differences compared with a conventional compressor, though. First, the automatic gain reduction is frequency‑specific. Second, the Gain setting limits the maximum amount of gain reduction applied by the EQ band. And third, there’s that Start control, which I’ll get to in a moment.

Because our EQ cut is dynamic, it is only applied when those pesky lower‑mid frequencies get out of hand; the rest of the time, when the guitar’s tone is more balanced, the EQ leaves it alone.

When the Internal side‑chain mode is selected, the ‘compressor’ takes its queue from the main incoming audio signal, and with the Auto button engaged the internal side‑chain adopts the frequency and Q values set in the main EQ Band. In most cases, including our example, this is exactly what you’ll want: our guitar’s low‑mids will be compressed most when those frequencies are at their loudest. Meanwhile, other frequencies will remain unaltered.

Turn Auto mode off, though, and you can adjust this internal side‑chain’s Frequency and Q manually; you can use the Listen button to audition the control signal as you make adjustments. While it’s not pertinent to our example, you can imagine other situations where using a different trigger frequency could be useful: for example, you could duck a hi‑hat in a stereo drum loop during kick or snare hits. You can also turn a band’s Side‑Chain section off, so that the full, unfiltered input signal is its trigger signal.

Screen 2. Frequency 2’s dynamics section can be used for expansion as well as compression.

Screen 2. Frequency 2’s dynamics section can be used for expansion as well as compression.

Start To Expand

The Start control enables you simultaneously to apply a static EQ cut and a further dynamic cut at the same frequency, without requiring two separate bands. As shown in Screen 2 for our ‘remove the mud’ acoustic guitar example, if we set the Start value at ‑3dB, the whole performance will have a static EQ cut of at least 3dB at 200Hz, but further gain reduction will be applied according to the Dynamics section settings, on top of this ‑3dB ‘starting point’. Again, the amount of gain reduction can be limited by the Gain setting in the EQ Band section.

The Start setting also makes frequency‑specific expansion possible. Imagine that with our acoustic guitar part, we wish to even out the dynamics of the upper frequencies (the ‘ching’ of the sound), making the quieter bits louder and the loud bits quieter. The settings for Band 8 in Screen 5 show an example configuration. Centred at 8kHz, the Start control has been set to add 6dB of gain. However, the main EQ Band controls are applying a 6dB cut. You can finesse the Threshold control so that, when these frequencies contain lots of energy, some downward compression will take place (to a maximum of ‑6dB, as defined by the Gain control) but, when there is less energy, some upward expansion can occur (up to the maximum of 6dB, defined by the Start control). The Attack and Release controls can then be adjusted to suit the tempo of the performance and ensure a natural result.

Chain Reaction

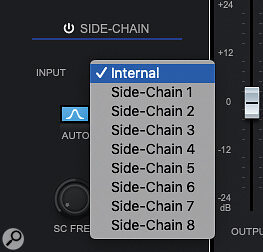

Screen 3. Frequency 2’s dynamics section can respond to several external signals.Frequency 2’s dynamics can also respond to an external side‑chain signal, activated by a button in the plug‑in’s toolbar strip. Indeed, click the Settings button and you can specify up to eight different external side‑chain inputs, each of which can have multiple audio sources, and use any one of these side‑chains for each of Frequency 2’s eight EQ bands (Screen 3).

Screen 3. Frequency 2’s dynamics section can respond to several external signals.Frequency 2’s dynamics can also respond to an external side‑chain signal, activated by a button in the plug‑in’s toolbar strip. Indeed, click the Settings button and you can specify up to eight different external side‑chain inputs, each of which can have multiple audio sources, and use any one of these side‑chains for each of Frequency 2’s eight EQ bands (Screen 3).

In Screen 5, an instance of Frequency 2 is inserted on a synth pad. Typically, pads such as this will occupy a wide frequency range, and thus sometimes mask other sounds, but they’ll only play a simple supporting role in the mix, making them musically less significant than the other parts.

Here, three dynamic EQ bands have been activated, with each targeting the most important frequencies of a bass, a rhythm guitar and a lead vocal (80, 250 and 350 Hz, respectively). Three side‑chain inputs have been configured, one for each of these three instrument groups.

Screen 4. Selecting a side‑chain signal for a Frequency 2 EQ band.

Screen 4. Selecting a side‑chain signal for a Frequency 2 EQ band.

This tactic can be really helpful in nudging pads out of the way of more musically important sources.

Screen 5 shows the settings used for the 350Hz EQ band. This uses the third external side‑chain input, which in this case is the signal from the lead vocal channel. The Dynamics section is configured to duck the pad by a few dB around this frequency only when the vocal is present. The other two bands, with the bass and guitar as the external side‑chain inputs, are configured in much the same way but target different frequencies and operate at different times. This tactic can be really helpful in nudging pads out of the way of more musically important parts: you can preserve clarity in the mix, without sacrificing a pad’s overall sonic texture.

Screen 5. In this example, a pad sound has three dynamic EQ bands controlled via external side‑chain inputs. EQ Band 4 is shown here in SING view and uses the lead vocal sound to duck the pad’s frequencies centred around 350Hz.

Screen 5. In this example, a pad sound has three dynamic EQ bands controlled via external side‑chain inputs. EQ Band 4 is shown here in SING view and uses the lead vocal sound to duck the pad’s frequencies centred around 350Hz.

It doesn’t take much imagination to think up more applications for Frequency 2’s dynamic EQ facility. Whether you need to clean out the lower‑mids on busy guitar or synth parts, tame the splashiest excesses on a drum bus, combine de‑essing and plosive control on a vocal track, or combine frequency‑specific compression and expansion to add a little extra dynamics to your mix bus, the possibilities are considerable. Increasingly, I find I’m turning to Frequency 2 as a one‑stop alternative to EQ and compression, and this is definitely a topic to return to. Until then, have fun experimenting.