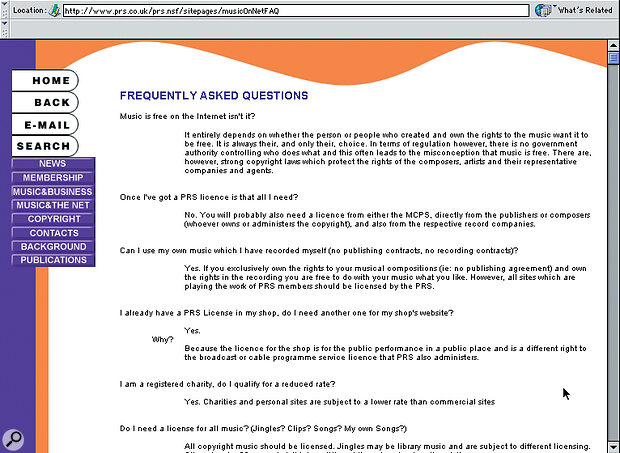

The Performing Right Society's web site addresses copyright issues surrounding distribution of music over the Internet

The Performing Right Society's web site addresses copyright issues surrounding distribution of music over the Internet

Dave Shapton explores copyright issues raised by new digital media and the effect of emerging technologies on the way that music is distributed.

<!‑‑image‑>Ask anyone who knows about the technical side of digital audio, or a programmer who understands digital media, and they will tell you that you can't copy‑protect music. Ask anyone in the music business (which includes copyright organisations, record companies, retailers, distributors, and manufacturers of music reproduction devices) and they'll tell you that you can. Now, before I go on, I've got to say some things that are rather like the statutory stuff you see at the end of a mortgage advertisement.

I support the concept of copyright. I think it's fair that the creator of a piece of music should have the right to control the circumstances of its use. I believe it is important that creators of music should be able to benefit financially from the use of their work, not least because if they didn't, very few people could actually afford to work in the music business. I am not an expert in copyright, but I have worked for a number of years at the Performing Right Society and I still support its aims and objectives, if not necessarily its attitude towards the effect of emerging technologies on the way music is distributed. I believe it is wrong to make unauthorised copies of recorded music. There are programs available on the Internet that allow you to exchange files — which could be music files — with other users. These programs (of which Napster is an example) set up your computer as a server, and could potentially allow other users to search and modify the contents of your computer. Anyone using these programs — and for that matter, anyone connected to the Internet at all — is susceptible to violations of their privacy by other Internet users. When I mention programs like Napster I am not condoning their use, nor am I prepared to take any responsibility for any consequences of their use as a result of anyone reading this article.

Digital Dilemma

www.zdnet.co.uk report on the AOL Deutschland case.

www.zdnet.co.uk report on the AOL Deutschland case.

My brief in writing Cutting Edge is to bring news of technological advances that may have an effect on the music industry. Well, it's slowly dawning on the music industry that there is a technology which could wipe it out completely, and it's in a state of apoplexy. I have to say that the music industry is not alone in this. The banking sector is in chaos at the moment because of the Internet: one large American bank readily admits that it is in 'panic mode'. It has sent its top 50 executives on retreat for several months to figure out how to survive in a world where its services are rapidly becoming redundant.

<!‑‑image‑>Now, imagine you're a record distributor or a record company and one day you wake up to find that you can type the name of practically any recorded track into just about any computer and within minutes, if not seconds, be listening to that track. Suppose that you could download whole albums for nothing: not even the cost of a telephone call. What if you could copy those tracks onto a CD‑ROM and put them into a special player connected to your stereo? And if you could fit 150 of them onto a CD, or nearly 10,000 of them onto a hard disk (costing £200) in the same device?

This is not science fiction — although it would have sounded like it as little as a year ago. I can do all of the above now, in my own home. How do you think record companies would react to the news that, in American colleges and universities, 70 percent of Intranet bandwidth is being used for copying music? Notice that I said Intranet, not Internet. It's not difficult to hog a modem line with a music download, but colleges and universities don't have to use modems: they have Internet links that are 10 to 100 times faster. An average college network supplies 10Mbit/sec to the end user. With the usual network overheads that's enough for about 40 simultaneous real‑time MP3 downloads, or 100 if you are prepared to wait for a half‑speed download. Apparently there are enough Napster users on an average campus for them not to have to go out to the Internet to get their material, although of course all the music files on the college network are available to Napster users worldwide!

<!‑‑image‑>So far, the response from the music industry has been to go to court, and in doing so all they have achieved is to demonstrate just how little they understand what is going on. Let's take a look at one example. On 11th April this year a German software company succeeded in an action against AOL Deutschland, in which it complained that AOL had been responsible for allowing the distribution of pirate copies of the company's software. The German courts ruled that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) such as AOL are responsible when unauthorised copies of intellectual property are downloaded through them. The German equivalent of the Performing Right Society and Mechanical Copyright Protection Society, Die Gesellschaft für Musikallische Aufführrungs und Mechanische Verfielfältigungsrechte, (mercifully abbreviated to GEMA) claimed it was a victory because it "means that you have to pay to use music on the Internet". So that's all right, then? No. It really isn't. Putting aside the special case where an ISP may have content that is only available to its own users, an ISP is just part of the infrastructure of the Internet. You don't even have to have an ISP to access the Internet (see box below).

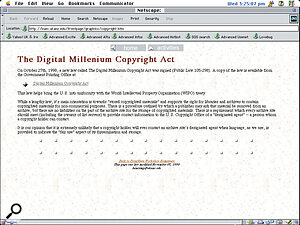

An alternative to 'making it up as you go along', which is what the judge in the AOL Deutschland case did, is to make laws that specifically outlaw Internet copyright piracy. There is such a law in the US called, grandiosely, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. This is the law that popular beat combo Metallica invoked recently when it sued Napster, Inc and (amongst others) Yale University for alleged violations of copyright. This action was first reported in the UK mainstream computer press, a sign of the significance of these lawsuits. Apparently the DMCA seeks to ban devices that "could be used to circumvent copyright". Better hide those phono leads then. Oh, and trash your Minidisc recorders, CD recorders, computers and 4‑tracks; plaster up your mains sockets, close down the local power station, and junk your car in case you're tempted to drive to the shops to buy a blank cassette tape.

Sound Solutions?

Legislation recently passed in the USA, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, has attempted to put a stop to Internet music piracy. You can find a link to it at kuec.ukans.edu/frontpage/graphics/copyright.htm. However, this new law has been unable to materially reduce copyright infringement.

Legislation recently passed in the USA, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, has attempted to put a stop to Internet music piracy. You can find a link to it at kuec.ukans.edu/frontpage/graphics/copyright.htm. However, this new law has been unable to materially reduce copyright infringement.

I won't waste any more time demonstrating what by now should be obvious: that these cases are absurd. Except to say that absolutely any attempt to control what passes to and fro on the Internet is fraught with difficulty, if not impossibility. Let's say that Parliament, in its wisdom, passes a law that states, quite simply, that it's illegal to swap MP3 files on the Internet. Fine. We can avoid ever breaking that law by renaming our files •.NP3 (which I suppose could stand for Not MP3). In fact, to avoid even the possibility of confusion, why not leave off the file extension all together? It would be perfectly simple to write an MP3 player that just looked at the content of the file to see whether it was playable or not.

File extensions aren't going to fool anyone for long. If you really wanted to disguise what you are sending you could encrypt your file, so that it would be a meaningless string of numbers to anyone without the key. You wouldn't even need to have the key on your computer: it could be accessible from a web site that you access before you play each track. What I am saying is that you simply can't control what is sent to and fro on the Internet.

So what about the Secure Digital Music Initiative, or any other kind of music copy protection scheme? Well, if you are a record company you are perfectly entitled to encrypt your music in the most complex way imaginable, and to make sure it will only play on devices that comply with the scheme. And you will no doubt be able to explain to me how you can stop someone playing the music from this device straight into the input jack of their soundcard for conversion to MP3 and 'publishing' on the web. And you'll presumably be aware that there is a massive trend towards playing music on 'computer' rather than dedicated devices, and that these 'computers' will have wireless connections to the Internet and will therefore be able to download software that will crack any kind of encryption you devise within seconds. If you think that won't happen, then just look at the ease with which DVD encryption was broken.

I'm sure some of you will conclude that I'm an anarchist plotting the downfall of the music industry. Well, I'm not. As I said above, I support copyright. But as I also mentioned, you can't copy‑protect music and because you can't, the genie is well and truly out of its bottle. I'm perfectly happy to accept that I'm wrong about all of this, but I don't think I am. I think the only way we can salvage anything from this mess is to embrace the reality of Napster and its new sibling Wrapster (which does the same thing but with any kind of file, including uncompressed WAV files — ideal for downloading with your new, free‑access Internet connection).

Why not change the law to encourage music copying on the Internet, but at the same time make it very clear that every track you download must be licensed individually. Impossible? No. We have the infrastructure in place already. It's called the High Street and it's where you find record shops. Make the licence in the form of a silver disc with a Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) encoded copy of the track to be licensed. Put some nice sleeve notes with it and possibly some entertaining multimedia content. Make sure it adds value to the lower‑quality downloaded file and make it an attractive product that will appeal to people's collecting instincts. Make record shops nice places to visit, but, above all, make the license cheaper than the things we used to call CDs.

To ISP Or Not To ISP

If you are big, or rich enough, you can have your own direct connection to the Internet. Actually, to say that you 'connect to the Internet' is a misleading way of putting it, because what you actually do when you connect to it is that you become part of it. That's what ISPs are: just part of the Internet. So, if you want to stop me copying MP3 files from someone in Brazil, who do you sue? Suing the ISP is about as clever as suing the company that made your water taps when you find you've got E‑Coli in your water supply. There are so many analogies that make this type of legal action pointless and unjustified. Why not sue Ford because Transit vans tend to be used in bank raids? (Legal disclaimer: other makes of van can be used in bank raids!)