The DVD format may be the coming thing, yet DVD players' fixed functionality leaves them less versatile than even a games consoles.

The DVD format may be the coming thing, yet DVD players' fixed functionality leaves them less versatile than even a games consoles.

The audio industry is gearing up to fully embrace DVD — but, as Dave Shapton argues, there could be a better way...

<!‑‑image‑>On the face of it, DVDs might not appear to have much to do with music. But DVD‑type discs are poised to become the carrier for two high‑resolution consumer audio formats: DVD Audio and Super Audio CD. One possibility, though, is that the success of the DVD disc in spawning new formats could be its own undoing.

Digital History

If DVD players were more versatile 'computers', they could be future–proofed, capable of dealing with whatever new audio format came along. Consider your desktop computer, which will often go and retrieve what it needs to read the formats it's presented with.

If DVD players were more versatile 'computers', they could be future–proofed, capable of dealing with whatever new audio format came along. Consider your desktop computer, which will often go and retrieve what it needs to read the formats it's presented with.

The 16‑bit, 44.1kHz CD is around 17 years old. A whole generation has passed since analogue audio lost its exclusivity on the shelves of record shops. Seventeen years is not bad going for any recorded music format, although it's no less than we should expect, if the lifespans of previous successful formats are anything to go by.

So how long is DVD going to last? Well, it's had a good start (better than CD at the same stage of its life span). With so much going for it — high capacity, great pictures and sound, and rapidly decreasing hardware costs — DVD looks as though it could be the next major media success.

But it might not be. There are several reasons why I say this, not the least of which is that when you think about what's happened to media technology (and that means computers!) in the last 20 years, it's very, very hard to imagine where our recorded music will be coming from 20 years hence. Even today, some of the supposed advantages of DVD are threatening to make it look as 'cutting edge' in five years time as a 486 computer looks now.

And that's not surprising when you consider that the DVD standard was finalised in 1996 and was in development for several years before that. Remember when CD‑R first appeared? For a long time the blanks cost between £15 and a fiver, which actually seemed like a bargain, because they stored 650Mb at a time when the hard disk in your computer was probably around half that size. As long as your data was text‑based, you'd struggle to fill a CD. I can still fit all my personal documents and every article I've ever written onto a single CD‑R.

Size Matters

CDs, by definition, are pretty good at storing audio. That's what they were designed for. The idea of using them for data storage was actually something of an afterthought. As everyone knows, a CD has enough capacity to store just over an hour of uncompressed 16‑bit audio at 44.1KHz. What comes as a surprise to most people is that the same CD will store less than a minute of uncompressed video!

Before DVD became a commercial proposition, the film and TV industries had the same kind of motivation as the music industry to move content distribution to a digital carrier. Vinyl records used a technology that was the best part of a hundred years old, and sounded like it. Compact cassettes could sound remarkably good, but were based on flimsy, fallible tape that was slow to rewind and expensive to duplicate. Film and TV programs were sold on VHS tape, a format that was not even as good as other formats around at the time when it became the standard for video distribution. (VHS tape has the dubious honour of being the worst‑ever commercial tape medium for reproducing audio. Before Hi‑Fi VHS was invented, audio was squeezed into a track only 1mm wide, right on the edge of the tape, where it was most likely to get damaged. Worse still, this track is split into two for stereo. And it doesn't help, either, that the linear tape speed is very slow.)

But several things had to change before three‑hour feature films could be sold on a disc the size of a CD. First, there had to be a way of making video occupy less space. Three hours of studio‑quality video would need roughly 1Gb capacity per minute. That's 180Gb, roughly 270 times more than a CD can cope with. Then you've got to find space for multiple language soundtracks, each in six‑channel surround format, plus all the 'extras' that people expect when they buy DVDs — such as "how we made this impossible‑to‑make film", and so on...

Using data compression, video can be processed to take up less space. MPEG‑1 (the audio part of which is used to create MP3 files) makes it possible to fit up to an hour of video onto a conventional CD. There is actually a standard which defines the use of MPEG‑1 to create Video CDs, but it never took off in Europe or America. The trouble was that Video CD didn't even look as good as VHS! And, of course, if you wanted to watch a feature film you'd have to swap discs two or three times. So, secondly, there had to be more capacity.

The way DVDs fit more data onto a disc the same size as a CD is to make the 'pits' engraved by the cutting laser smaller, and they do this by using a blue laser instead of a red one. Blue light has a shorter wavelength than red and can be focused onto a smaller spot. To cram still more information onto the disc, both sides can be used, and each side can have two layers, accessible by changing the focus on the laser in the DVD player. Add all this up and you get a whopping 17Gb. Sounds like a lot, doesn't it?

Until you remember that you need 180Gb for three hours of uncompressed video. Which means that we're still short by a factor of 10, or 20 if you want to avoid having to turn your disc over in the middle of a film.

Still, at least we don't have to rely on sub‑VHS quality MPEG‑1 and can use the milder, kinder, MPEG‑2 compression, which can just about shoehorn a threehour movie onto a single DVD. But not without a lot of effort and some tears, because without quite a lot of manual intervention in the encoding process, you actually can't fit a whole film plus extras onto a single DVD.

Standard Practice

Now when the DVD standard was ratified in 1996, 17Gb probably sounded like a technological triumph. And you could argue that if you can fit a feature film on a DVD — which is, after all, the format's raison d'etre — then it's a done deal. But it looks now as though DVD is actually spawning a whole dynasty of formats, several of them to do with audio. The presence of these just might confuse the public enough to let downloaded media — audio and video — become the model for music use sooner than the music industry would like.

I'll show you what I mean. Just look at this paragraph from What Video and TV magazine, dated February 2001, about Phillips' SACD100 Super Audio CD player: "The SACD1000 features six‑channel output and will play DVD‑VIDEO, VCD and CDDA discs. It will also be compatible with audio‑ and video‑related formats, including DSD, PCM, MPEG2, Dolby Digital and DTS, as well as supporting CD‑R and CD‑RW."

Hang on a minute. What's happened to this nice, marketing‑friendly concept that says "DVD is just movies on a CD"? And what chance has either DVD Audio or Super Audio CD got when you can't even tell if it will play in your deck without drowning in a sea of acronyms that could have come from the script of Apollo Thirteen!

<!‑‑image‑>If you've ever heard 24‑bit, high‑sample‑rate audio, or 1‑bit, very‑high‑sample‑rate audio, you'll know that audio CDs are, at best, a compromise. They're fine for mini hi‑fis and in‑car entertainment consoles, but it's now widely recognised that they can't deliver the ultimate in digital audio reproduction. That's why I support the drive to produce a mass‑market high‑resolution audio format. But I don't know if it's going to be based on DVDs.

You see, to make the DVD a standard, everything about it had to be decided in advance. There was no way around that, because until the format was finalised, no one could build a commercial DVD player. But the very thing that has made DVDs such a success in the short term — being able to play a DVD on any DVD player — is what might stop it being adopted in the long term as a universal digital media format.

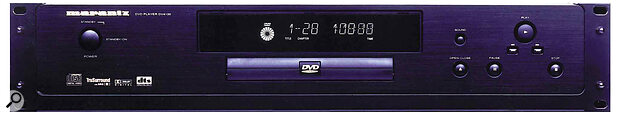

Even now, such a short time into DVD's life span, it's beginning to look clunky. No amount of pretty graphics can disguise the clumsy way in which DVDs operate. I'm not into computer games, but I can't help noticing that games consoles — which cost about the same as DVD players, and some of which, ironically, play DVDs — can interact with their users in ways that manufacturers of DVDs can only dream about.

That's because games consoles are computers. DVD players are computers in a sense, too, but they are only allowed to run one program: the one that plays the DVD and sets up a very limited amount of interactivity for the user.

Remake, Remodel

If you've got this far you're probably wondering whether you've picked up the wrong magazine. What on earth has this got to do with music technology? A lot, actually.

Quite simply, if you put more processing power into a DVD player (remember, they cost about the same as games consoles) you don't have to define the structure of the data medium (i.e the DVD) so tightly. Here's where the music and record industry needs to sit up and listen.

What I'm suggesting is that we abolish the present structure of DVDs and replace it with... a file system. Just like CD‑ROMs. Just like DVD‑ROMs, in fact.

What difference would this make? All the difference in the world. The difference between the sort of computer you have in a microwave oven and the sort of computer you have on your desktop. Ever tried getting your microwave to change the way it displays the time? Ever tried downloading stuff from the Internet on your Microwave?

Of course, you can't. You can't do it with the average DVD player either. The only way you can add to or change the functionality of a DVD player is to bring out a new type of player. And you'll have to keep doing that until you run out of new types of consumer format. But of course that won't happen, because the average guy in the street, who typically doesn't have a deep understanding of compression algorithms and embedded processors, will have given up a long time ago and will simply boycott the new formats. Or he'll carry on downloading stuff onto his computer.

Yes, there are dozens of audio and video formats out there on the Internet. Enough to confuse the best of us if we really stopped to think about it. But the thing is precisely that we don't have to think about it when we use our computer! Typically what happens now when we encounter a new media format is that we click on it and, without any intervention from us, our computer downloads whatever we need to decode and listen to or watch the file we're about to acquire.

So make DVD players computers. They don't have to be Windows or Mac based. Sony Playstations aren't! Treat DVDs as data‑storage devices. Put anything you like on them, as long as it includes the right codec to play the material on the disc. Put a Java‑like 'virtual computer' in the player's firmware, so that any software can run on any machine, regardless of the physical processor used.

And then feel free to issue a new super‑duper audio or video format every week, if you like.

Digital Format Birthdates

There have been remarkably few consumer digital audio formats since CD, yet now we're being showered with them. Here are the main ones:

- CD: Born 1980; Sony Philips; 16‑bit, 44.1 kHz. Major commercial success.

- DAT: Born 1986; Sony Philips; 16‑bit, 44.1 kHz. Abject commercial failure, except in professional circles.

- Minidisc: Born 1992; Sony; 44.1kHz, ATRAC compression. Minor success, but may be sidelined by success of MP3.

(Historical footnote: The Integrated Circuit, which is the basis of computer memory, was introduced by Texas Instruments in 1959. Since memory is now the latest digital audio format, it is also arguably the oldest!)