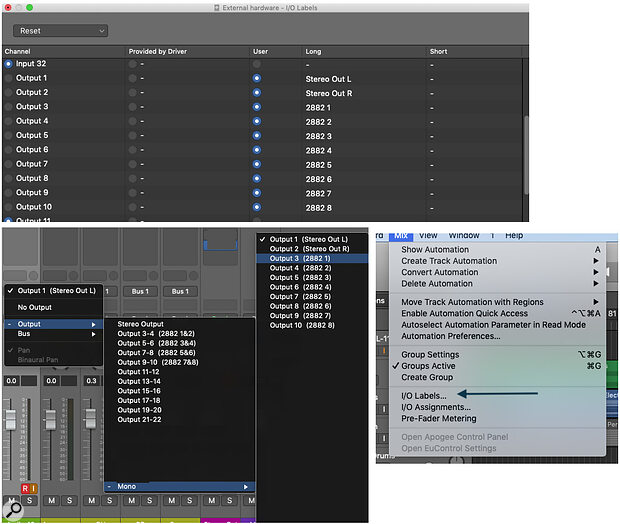

Screen 1: Setting up your ins and outs.

Screen 1: Setting up your ins and outs.

It’s not always obvious in Logic Pro X how to go about incorporating hardware into your workflow; we show you how.

Almost as soon as music began to be recorded digitally, engineers felt they were losing a certain ‘something’ from not driving the audio through tubes, transistors and transformers. As the emulation of analogue electronics has improved, many have moved completely ‘in the box’ for convenience and recall. It’s perfectly possible to create fine recordings using computer‑generated audio alone, as many a number‑one hit record will testify, but many of us still feel the loss of that ‘mojo’ that, we believe, analogue hardware can provide. The cost of adding this hardware to our studios has fallen dramatically in the last few years, with clones of classic gear and the 500‑series format providing entry‑level hardware that can be bought for very little. So, if you’ve ever wondered what adding analogue hardware would bring to your recording and mixing, there’s never been a better time to find out!

There are several ways you can use hardware with Logic Pro X: recording vocals or instruments, mixing, and mastering. If you treat these as three separate processes, a little hardware, re‑used, can go a long way. It’s not always obvious in Logic Pro X how to go about incorporating hardware into your workflow and much of the process will depend on your audio interface. Many interfaces have quite complex routing software, so a good peruse of the manual is recommended. If all you want to do is add a little compression or EQ on the way in, a basic 2‑in/2‑out interface will suffice, but you will need to have an insert point between the preamp and the analog‑to‑digital converter, or an external preamplifier, to achieve this. If you want to use external hardware when mixing, you’ll need more inputs and outputs. If you get hooked, you’ll need a lot of inputs and outputs!

If you look at the Input menu in a Logic Pro X Track, you’ll see the number of ins and outs that your interface’s driver is reporting to the DAW. The first thing to do is give these useful names using the I/O Labels item in the Mix Menu (Screen 1, above). If you are going to use specific ins and outs for specific hardware, here’s the place to make sure you always know where you’re sending and receiving your audio.

Mixing

Mixing is where I think the ‘mojo’ is most obvious when using hardware. I personally find that mixing into a hardware bus compressor, with other devices strapped across various separate tracks in a mix, really helps me find the ‘right’ sound much more quickly than using plug‑ins alone. So, a basic mix session might have a stereo compressor and EQ across the drum bus, a compressor and EQ on the bass and individual drums, a compressor and EQ on the vocals and another compressor (and perhaps other processing too) on the mix bus. To send audio to and from Logic Pro X to these hardware devices, you’ll mostly need to use Logic Pro’s I/O plug‑in, shown in Screen 2.

Screen 2: Logic Pro’s I/O plug‑in.

Screen 2: Logic Pro’s I/O plug‑in.

If you insert this on, say, a drum bus, you can set the input and outputs of the physical interfaces that you’ve plugged your bus compressor into. Send and return levels enable you to adjust the amount of gain, which is especially useful when you’re trying to hit a transformer input hard for some ‘colour’, and to adjust the level returned to the track. A nice feature is the Dry/Wet control. If you have a compressor on the vocals, say, and want to try parallel processing, you can adjust the blend between compressed and dry signal here. You will also need to hit the latency detection Ping button before playback begins. This sends an audio ‘blip’ through your hardware and back to Logic Pro to gauge the time the signal takes to pass through the interface and hardware and back. If you add another processor to the chain you’ll need to do a Ping again. Even if the latency detection is a few milliseconds out, it can play havoc with phase.

If you add a plug‑in before the send to the I/O plug‑in on a track, a thus processed sound will be sent to your external hardware. However, if you want to process the audio after it’s travelled through the hardware, you’ll need to don a monk’s habit and enter that arcane place called Logic Pro X’s MIDI Environment...

First, send the audio from the track you want to process to the physical output your hardware is connected to, using the I/O plug‑in but with its input set to off (the ‘‑‑‑’ in the drop‑down menu). Create an audio track (stereo for a two‑channel processor, of course) and give it a useful name. Keep that track selected, and click Window / Open MIDI Environment. Find the Mixer layer and the selected audio track and then, from the Inspector’s Channel menu, change the track type to Input Track, set its inputs to the ones you’ve plugged your hardware return into, pull down its fader and leave it as ‘No output’. Back in the Mixer, you’ll now see audio running from your recorded tracks, into your hardware, back through the input track you created and then out through the stereo master, as in Screen 3. Adding plug‑ins to this new input track will allow you to process the audio after it has passed through the hardware.

Screen 3: Routing in Logic Pro X’s Environment.

Screen 3: Routing in Logic Pro X’s Environment.

Summing

Now, summing is quite a controversial process, with some saying it’s a complete waste of time, and others claiming you need dozens of outputs to make it worthwhile. But with low‑cost 500‑series transformer‑based summing boxes and inexpensive high‑quality mixing desks available new and used, you don’t need to spend a lot to see if summing will be right for you. Obviously, if you’re using all your inputs and outputs for mixing, you’re not going to be able to use these for summing as well. The obvious solution would be to buy extra inputs and outputs (ADAT expanders are one possibility), but there are other ways to get around this issue without spending more moolah.

Send and return levels enable you to adjust the amount of gain, which is especially useful when you’re trying to hit a transformer input hard for some ‘colour’...

Let’s assume you have eight channels of I/O available and an 8:2 summing device. Once you are happy with your mix, you’ll need to bounce down the hardware‑processed tracks and busses to audio files by soloing them and using the Edit / Bounce menu. Although Logic Pro has a ‘bounce in place’ feature, this won’t work with hardware, so you’ll need to render audio in ‘real time’. If you are using hardware across a bus, just solo this and bounce it down. Now re‑import the audio back into Logic Pro — I like to record it into a new Project Alternative (which you can create in the File menu). Once you have your bounced tracks as audio, you can then re‑patch the physical outputs into your summing device.

You’re unlikely to have enough outputs, or summing device inputs, for all of your tracks, so you’re also going to have to submix some of your tracks to busses. For example, if you have eight outputs available, you could assign these thus: two to a stereo drum bus, one for vocals and effects, one for basses, two for guitars and two for keyboards. To route tracks to a bus, select them, then select a bus from the Output menu and rename the automatically created bus to something useful.

To send the audio from your busses to the hardware, select the relevant outputs in the bus’s Track Output box. To return the mix from your summing device, patch its outputs into two inputs on your interface, load an I/O plug‑in on your Stereo Master track and set its input to these physical inputs, and mute the output (Screen 4). You can also insert effects after the I/O plug‑in to further process the summed return. If you want to add plug‑ins before the return to the Stereo Master, you’ll need to create an Input object in the Environment, as before. You can also, of course, add more hardware on the outputs of your summing device for extra processing.

Screen 4: Routing for summing in Logic Pro X.

Screen 4: Routing for summing in Logic Pro X.

Patch Notes

How you ‘drive’ the inputs of your summing device, and the specifications of the device itself, is what will ultimately decide for you if summing is worth the extra effort involved. Your wallet is your oyster. For me, using hardware when tracking and mixing is a no‑brainer. It makes it easier to judge the mix, albeit at a cost of immediacy and, to an extent, recall. Summing is harder to justify, but if you have a mixer lying around (I use my SSL X‑Panda) it’s definitely worth a go. But be warned: if you do like what analogue hardware can do to your sound, you might need a bigger rack — and a patchbay!