Tom Rhea’s colourful, comprehensive and insightful history of electrical and electronic music machines includes CDs with audio examples.

When I was a kid, among my greatest joys was getting one of those Christmas toy catalogues in the mail. While my sister wanted the dolls and games and my friends all wanted the baseball gloves and football helmets, I salivated over techie stuff: transistor radios, electric trains and cars, building and highway construction sets, and walkie‑talkies. Opening Electronic Perspectives: Vintage Electronic Musical Instruments is a lot like poring over one of those catalogues, only looking backwards. It’s a huge and beautifully put‑together compendium of electrical and electronic musical toys, going back well over a century.

When I was a kid, among my greatest joys was getting one of those Christmas toy catalogues in the mail. While my sister wanted the dolls and games and my friends all wanted the baseball gloves and football helmets, I salivated over techie stuff: transistor radios, electric trains and cars, building and highway construction sets, and walkie‑talkies. Opening Electronic Perspectives: Vintage Electronic Musical Instruments is a lot like poring over one of those catalogues, only looking backwards. It’s a huge and beautifully put‑together compendium of electrical and electronic musical toys, going back well over a century.

Overview

Tom Rhea was the right guy to write this book. He is one of the sages of the electronic music era, having penned a column called 'Electronic Perspectives' for the late, lamented Contemporary Keyboard (later just Keyboard) magazine from 1977 to 1981. His PhD thesis, back in the days before the Minimoog (for which he wrote the owner’s manual), was on the evolution of electronic instruments. He had a 30‑year career teaching college courses in synthesis and synthesizers.

The book reflects the enormous knowledge Rhea has accumulated: it’s over 400 pages, and weighs upwards of seven pounds. All 51 of his columns are here, reproduced with their original layout and typefaces, accompanied by over 300 pages of illustrations, and bound in stiff cardboard with a hard slipcover. Attached to the back cover are two CDs containing some 53 musical examples totalling 1.5GB, some of which have never been heard before, and there are extensive notes about each track. It is, in one oversized volume, the history of electronic music, in words, pictures and recordings, from the pre‑vacuum‑tube era to the dawn of digital audio workstations.

Much of the information in his columns would still, even in the age of Google, not be easy to find.

What might be most remarkable about the columns, besides how well they hold up today, is that Rhea did all of the research for them the old‑fashioned way, long before there was an Internet. As musician and author Brian Kehew, who helped on the project, says in his foreword, Rhea used “card catalogues, engineering and music indices, telephone books, letters written, books in library stacks, old newspapers and magazines, [and] flights to interview pioneers using his cassette tape recorder”, as well as the New York Times on microfilm. Much of the information in his columns would still, even in the age of Google, not be easy to find. Stylistically, though, the columns don’t feel at all dated — Rhea’s conversational voice remains as pleasant to read as it is informative.

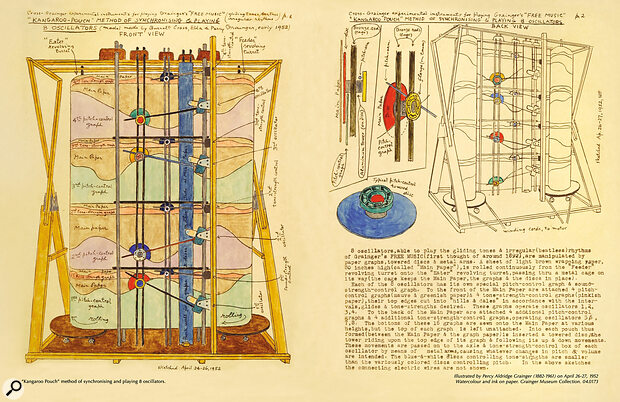

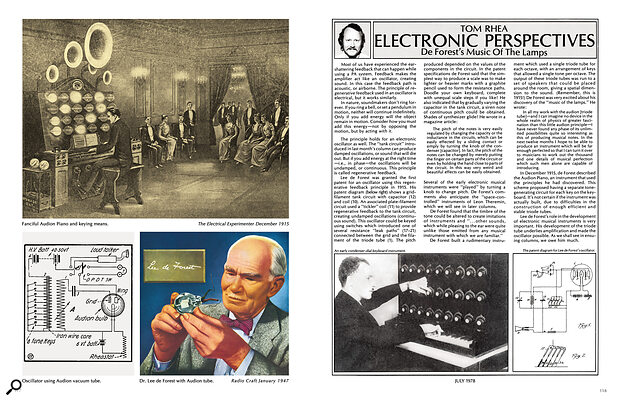

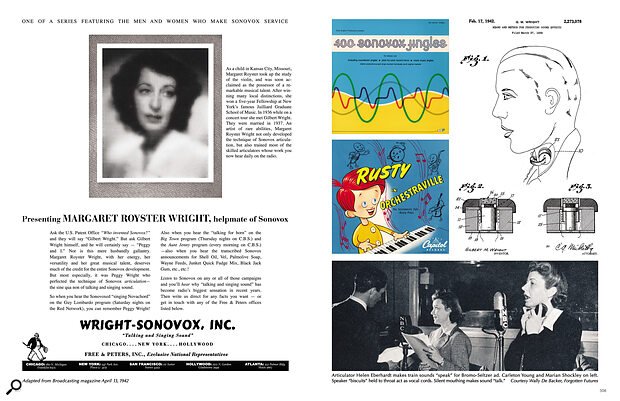

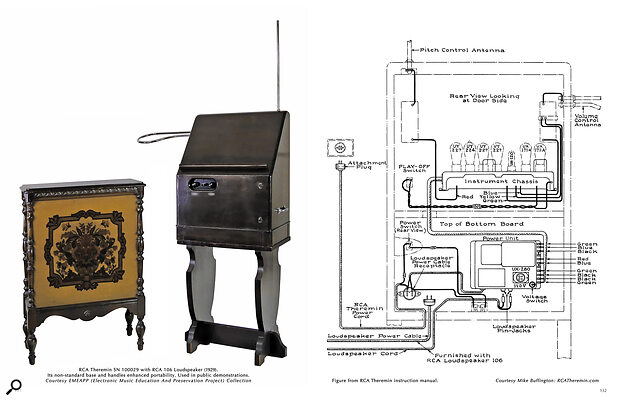

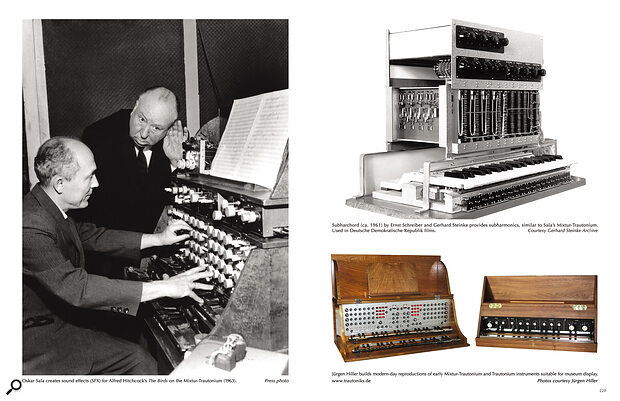

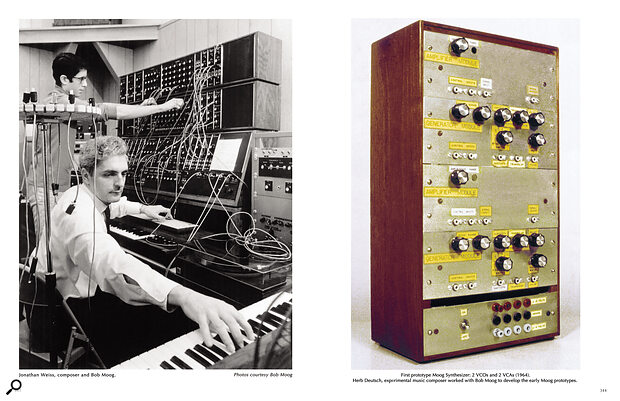

But while the columns form the basic framework of the book, they are enormously augmented by the work of graphic artist Joseph Bastardo, whose contributions include restorations of vintage ads, product brochures, concert programs, photos, patent documents, newspaper and magazine articles, and many other materials. As you can see from the sample spreads included in this review, they are simply gorgeous.

Some of the instruments the book covers will be familiar to today’s readers: the Theremin, the Wurlitzer and Rhodes electric pianos, the Hammond organ, and Robert Moog’s analogue synthesizers. Some others will be less well‑known: the RCA Mark II synthesizer, for example, which, with its 1700 valves, took (and still takes) up an entire room on 125th Street in New York City, and to which Rhea devotes six columns; the Ondes Martenot, invented in the 1920s but which still has active players in France and Canada; the Ondioline, conceived by Frenchman Georges Jenny in 1939 and used to great effect by Al Kooper on his seminal 1968 album Super Session; and Don Buchla’s keyboardless modular synths. There are also a lot of instruments and systems in the pages and on the discs that will probably be brand‑new to most readers, such as the Hellertion, the Electronic Sackbut, the Pianorad, the Clavivox, the Multi‑Track Tape Recorder (not what you think it is!) and the Cellulophone. And there are instruments made by well‑known inventors and companies that never got popular, such as: Hammond’s Solovox (presented here on disc by the legendary Sun Ra) and Novachord; Theremin’s Terpsitone and electric cello; Telefunken’s Trautonium; and an early electric piano from the German piano maker Bechstein.

Structure & Highlights

The book starts out with three essays about Thaddeus Cahill’s 1900 invention of the Telharmonium, an electro‑mechanical monster of an instrument that used dynamos (electrical generators) to produce powerful audio signals that were transmitted to subscribers in New York City in real time over telephone wires. It was, arguably, the first electric instrument to enter the public eye. It also pre‑dated other subscription music services by about 100 years! The size of 10 railroad freight cars, it occupied an entire building in midtown Manhattan, and required two musicians to play it. Although its means of tone production was revolutionary, its repertoire was hardly so: in order to attract subscribers, Telharmonium programs consisted mostly of light classics and popular tunes of the day. But despite huge investments in the instrument, and a formidable marketing campaign, it was a colossal failure. According to some who heard it, the instrument’s sound was impressive (Mark Twain pronounced himself a fan) but, alas, no recordings of it have survived.

Rhea organises the book in the chronological order in which his columns were published, and these don’t necessarily reflect the chronology of history. Yet this serves him well when he follows the Telharmonium columns with two on the Hammond Organ, introduced in 1933, which was in a technical sense a direct descendant of the Telharmonium: the dynamos were replaced by small metal wheels spinning alongside miniature electromagnets, whose output was amplified by now‑ubiquitous vacuum tubes. Unlike its predecessor, of course, this invention was a great success.

Later in the book he goes back earlier in time to what he calls the first ‘electronic’ instrument — that is, one that used nothing but circuitry to produce sound, with no moving parts: the Singing Arc of 1899. An English physicist named William Duddell discovered that if you attached a shunt circuit to a high‑voltage DC carbon‑arc lamp, you could make it oscillate in the audible range. The frequency of the oscillation depended on the components in the shunt circuit (resistor, inductor, capacitor) and thus you could design a keyboard that would play different pitches by varying the values of the components. There was no need for a speaker‑the arc itself produced plenty of sound! (The same principle is used today in the plasma tweeters found in some high‑end speakers.)

Following a column on Harald Bode’s Vocoder and Klangumwandler (frequency shifter), and audio demonstrations of both on the discs, are four pages on Bell Labs’ 1939 Voder keyboard‑controlled speech synthesizer, which they nicknamed Pedro (“About a year’s practice enables an operator to make Pedro talk glibly,” states an article from Popular Science magazine), and four more pages on the Sonovox, the first talkbox (which could also be used as an artificial larynx) from 1942.

This book also covers instruments that Rhea didn’t get a chance to write about in his columns. For example, he devotes six pages to the Choralcelo, a variation on a piano that used electromagnets to vibrate the strings so they could sustain tones, not unlike today’s EBow for guitars. Along with two pages of colour photographs, he reproduces an article from 1916 that calls it “the most wonderful musical instrument ever thought out by the human mind”. A sampling of it is the first track on disc 1, and it is indeed lovely, a cross between a piano and a seven‑octave flute choir.

The illustrations and the recordings on the discs expand greatly on the columns. Rhea’s essay on Leon Theremin’s various non‑keyboard instruments is followed by no fewer than 25 pages of illustrations (including a high‑school photo of Robert Moog playing his home‑built Theremin), and then a column on the Ondes Martenot, which used very similar electronics but presented a completely different user interface, is accompanied by 18 pages of pictures. On the discs are three Theremin tracks (including a multitrack performance by Theremin cousin and student Lydia Kavina of a piece by Percy Grainger), four Ondes Martenot tracks, and a demo of a 21st Century polyphonic descendant of the Ondes Martenot, the Haken Continuum Fingerboard.

The RCA Mark II, introduced in 1956, was the first digitally controlled synthesizer to get widespread recognition, if not use — only one was made and only a small handful of composers knew how to work it. Rhea gave it no fewer than six columns, in which he took the opportunity to explain sampling theory, binary numbers, how various electronic instruments approach the issue of portamento differently, and what is often lacking in the performance of electronic music. The corporate motivation behind the Mark II was not to create a new platform for experimental music, which is where it ended up, but to replace conventional musicians and studios with a single machine for playing and recording music. The tracks on disc 2 hardly support this notion: they are laughably wimpy and sterile!

Many, many more instruments and their inventors are profiled. The brilliant and secretive Raymond Scott and his Rhythm Modulator, probably the world’s first sequencer, and his automatic composing machine the Electronium (which was to be adopted by Motown Records head Berry Gordy, who also had visions of replacing humans), gets five pages and three CD tracks. Oskar Sala and the Mixtur‑Trautonium, used to great effect in Alfred Hitchcock’s horror film The Birds, is represented by four tracks. There are three columns about instruments that used light and photocells to produce music, and a total of 41 pages devoted to the evolution of the electric piano. And, of course, there are 24 pages about Robert Moog and his many innovations, from his first prototype to the Polymoog.

The final text entry is Rhea’s farewell column from June 1981, which for the first time talks about the role of computers in making music. “In my opinion,” he wrote hopefully, “the artistic — and commercial — success of the instruments produced in the next 10 years will depend more on the willingness of their designers to research and read existing literature on psychoacoustics and ergonomics (human engineering) than on startling technological breakthroughs.” But then came MIDI, and the musical instrument paradigm changed completely: the physical characteristics of an instrument no longer needed to bear any relationship to what it sounded like. Ergonomics, for a while, took a back seat to making sure we had the latest sounds, but as the recent explosion in alternative controllers shows, they’re getting attention once again.

A Book Worth Owning?

Electronic Perspectives: Vintage Electronic Musical Instruments ranks as one of the most valuable resources ever about the history of electronic music. Its combination of friendly text, beautiful pictures and unique recordings make it both useful as a reference and highly enjoyable to peruse. It’s not cheap, but it will live in your library for a very long time, and although it covers scores of obsolete technologies, it will never itself become so.

Pros

- A comprehensive history.

- Covers both familiar and less familiar instruments.

- Includes two CDs with audio examples.

- Gorgeous graphics.

Cons

- None.

Summary

A wonderfully compelling and thorough history of electrical and electronic musical instruments from the pre‑valve era to the dawn of computer music.