The MX2424 with its optional RC2424 remote.

The MX2424 with its optional RC2424 remote.

Tascam's MX2424 hard disk recorder aims to provide professional 24‑track digital recording features at an affordable price, combining the simplicity of tape recorder‑style operation with the flexibility of computer editing. Paul White finds out how well it achieves these aims.

<!‑‑image‑>Computer‑based multitrack recording now offers huge potential and flexibility, but alongside the benefits come complications and operational complexity. Many users prefer the simpler tape‑recorder paradigm where you select a track, adjust the input level and start recording. But tape takes time to rewind, the amount of editing you can do is very limited (unless you resort to an external computer system) and modular eight‑track digital tape systems take a finite time to sync up, which can be a real distraction when you're trying to handle a lot of punch‑ins.

Despite the falling cost of disk‑based non‑linear digital recording systems over the past few years, and the attractiveness of the editing options they usually offer, many people have stuck with tape‑based systems because of the low media cost and easy archivability associated with them. However, few people would deny that the idea of a 'tapeless tape recorder' now looks increasingly attractive. What I mean by such a device is a hardware, disk‑based recording system that emulates the operational methodology of a multitrack tape recorder, right down to the way it handles punch‑ins, without introducing problems such as latency, instability or an inscrutable operating system.

Of course, we've had devices like this for several years, with companies such as Fostex and Akai makingsome of the more approachable devices at the affordable end of the market, balanced by systems such as the Otari RADAR at the high end of the scale — but now a new generation of machines is appearing, spearheaded by the Tascam MX2424 reviewed here (a joint development with US company Timeline) and the 'imminent' but as‑yet‑unreleased Mackie HDR24/96. The main difference between these machines and what has gone before is that although they are both priced to appeal to the project studio market, they come with 24 tracks as standard, they can record at up to 24‑bit resolution, and both are planned to operate at 24‑bit/96kHz at the cost of limiting playback and recording to 12 tracks. At the time of review, however, the Tascam MX2424's 96kHz function is not yet operational, and will remain so until a software update due later in the summer. The existing 24‑channel analogue I/O option (more of which in a moment) is already 96kHz‑capable, and is able to auto‑switch between sample rates.

<!‑‑image‑>Both Tascam and Mackie machines furnish the user with tools to undertake editing of the recorded material, and also address the issue of archiving from disk in a practical way, by offering drive options for backup purposes — and handily, the MX's built‑in backup software only backs up newly recorded audio, so you don't have to wait for a complete project to back up every time. Tascam's MX2424 requires an external PC or Mac to provide its visual editing environment via the supplied ViewNet software (see the box on page 136), though essential cut/paste/move/insert editing can be handled directly from the front panel. Mackie's HDR24/96 system is likely to cost more than the Tascam MX2424 by the time appropriate I/O has been installed, though this is balanced to some extent by the fact that it accepts a conventional monitor screen, keyboard and mouse without the need for an external computer. On the other hand, multiple MX2424s can be controlled from a single computer. Both machines are purely recorder/players, so mixing needs to be undertaken using a separate mixer. However, this is not the place to compare the two machines further, as full details about the Mackie are not yet available.

Meet The Mx

The review MX2424 came preloaded with the IF AD24 ADAT option and the 24‑channel IF AN24 analogue input card.

The review MX2424 came preloaded with the IF AD24 ADAT option and the 24‑channel IF AN24 analogue input card.

Housed in a deep 4U case, the Tascam MX2424 looks very much like a 24‑track version of a modular digital multitrack, with bar‑graph metering for every channel as well as conventional track‑arming buttons and familiar transport controls. Unlike a tape machine, up to 999 virtual tracks are available per Project — the standard name for a work‑in‑progress on the MX2424 — and these tracks may be loaded into any playback track as required, whether the destination track is in the same Project or a different one. There's no numerical limit on the number of Projects you can create — this is determined only by the storage capacity of the attached recording drive (or drives — see below). The MX2424 ships with an internal 9.1Gb hard drive, which stores around 1200 to 1800 track minutes depending on the recording format you use. This in turn equates to around 45 minutes of 24‑track recording.

Because not every user will have the same I/O requirements, the rear panel of the machine accepts a number of plug‑in options for both digital and analogue compatibility, with one set of stereo S/PDIF (and AES‑EBU) inputs and outputs fitted as standard, which may be set to address any pair of tracks with sample‑rate conversion. Currently available are I/O modules in ADAT optical, AES‑EBU, analogue, and TDIF formats (see the 'Prices & Options' box). The AES‑EBU module supports input sample‑rate conversion, though this may be switched off. Single‑wire or two‑wire 96kHz support is also provided, although two‑wire support requires the AES‑EBU option as only one pair of AES‑EBU connectors is available on the standard machine.

<!‑‑image‑>Each I/O module provides 24 channels in and out, and there's room to fit one analogue I/O module plus one digital I/O module. This is a very flexible system, as the user can configure the inputs to access any combination of analogue and digital channels (in blocks of eight inputs) as required. The analogue and digital I/Os are available simultaneously, which could be very important to those users recording via analogue preamps but monitoring through a digital mixer connected to the digital I/O port.

Aside from the internal drive, there's no shortage of further recording and backup options. A 5.25‑inch expansion bay on the front panel enables the user to fit either a DVD‑RAM drive or a Travan tape drive for backing up data from the internal drive. Using the DVD‑RAM drive, it should be possible to audition pairs of tracks prior to loading, as the plan is for the recorder to simply 'see' the DVD drive as another connected hard drive. This feature could be useful for loading in stereo sound effects, sample loops and suchlike. Unfortunately, no drive was fitted to the review model, so I wasn't able to test it.

A rear‑panel LVD SCSI interface is also provided as standard (a balanced variant allowing a much longer cable connection than 'ordinary' SCSI), so the user may also choose to back up to other SCSI media. Hard drives attached to this port, or installed in the front bay, may also be used for recording and playback.

In order to provide a degree of compatibility with mainstream computer‑based workstations, the MX2424's hard drive is formatted to the HFS standard (as used in Macintosh computers), though it is planned to extend the options to HFS Plus and Windows‑compatible FAT32 later this year. Audio files can currently be stored in Sound Designer II format only, but when the FAT32 disk format option becomes available, use of Broadcast WAV files will also be possible (these can read by any WAV‑compatible devices, but unlike ordinary WAV files, provide additional time‑stamping information embedded in the file. Easy interfacing with other Digital Audio Workstations (or DAWs) is made possible by the MX2424's use of the Open‑TL Edit Decision List (EDL) format, as already used by SADiE and Waveframe systems and now also Steinberg's Nuendo (see review on page 158 of this issue).

The SDII format allows the files to be read by systems such as Pro Tools, and similarly, Pro Tools audio files can be imported into the MX2424. When using a Mac‑formatted drive the MX2424 reads/writes time‑stamped SDII audio files. This provision ensures correct sync when exporting MX2424 audio files into Pro Tools, which can be done by connecting the SCSI drive directly to the Pro Tools system. When projects need to be moved between hardware and computer platforms, the user can format the drive with the MX2424, record audio and then physically take the drive to the computer. Interestingly, 16‑bit and 24‑bit files may be used in the same project, so it's possible to load in a session recorded at 16‑bit resolution, then add overdubs at 24‑bit or vice versa (when 16‑bit files are imported for use in a 24‑bit project, the 16‑bit files are played back as 24‑bit signals, with dither used to create the additional eight bits.)

A number of sync options are fitted in order to allow the machine to slot into a number of different professional audio and AV environments. No doubt much of this technology is due to Timeline, who specialise in sync systems, so in addition to SMPTE read and write, there are MTC (via the MIDI In, Out and Thru sockets), MMC, Word Clock In, Outand Thru connectors, and Video Sync In and Thru sockets that enable the MX2424 to lock to black‑burst or colour bars from either PAL or NTSC signals. Finally, the TL‑bus connector allows multiple MX2424s (up to 32) to be sync'ed together. This means you could have a total possible track count of 768 (not counting virtual tracks), though I think it's safe to say that few users are likely to test this limit!

Other rear‑panel connectors include a footswitch jack for hands‑free punching in or out (this socket also accepts a connection from an Alesis LRC for basic transport control), and a 9‑pin 'D'‑connector which links the machine to the optional RC2424 remote controller. The remote duplicates all of the MX2424's front‑panel functions, including the Jog/Scrub wheels, and also allows you to select which MX2424 it will address when you're running a multiple‑machine setup (the remote control itself can 'only' address up to six machines, but this is hardly a limitation).

Power for the remote control unit comes from an external power adaptor. This has an IEC connector so an extension cable of any length can be fitted, but it still leaves you with a 'lump in the line' to be accommodated somewhere. Having power supplied directly from the recorder via the multicore would have been neater. When using an external computer to run the ViewNet graphical user interface, the host computer is connected via Ethernet. The software is Java‑based, so it will run on either Macs or Windows 95/98 & NT PCs, and in addition to providing visual editing, it also allows access to the machine's setup menus, which is probably easier than configuring everything from the front panel. ViewNet offers track‑based cut/copy/paste/move/insert editing plus the ability to reverse sections of audio, but more comprehensive functions, including waveform displays, will only arrive when the operating system software is updated later in the year.

The Control Surface

The optional RC2424 remote duplicates all the MX2424's front‑panel controls, but lacks its metering.

The optional RC2424 remote duplicates all the MX2424's front‑panel controls, but lacks its metering.

The front panel has a distinctive look, due mainly to the use of triangular track select buttons and the unusual but ergonomically sensible array of buttons set out around the Shuttle/Scrub wheel (see below). Many of the front‑panel keys also have a secondary function accessed via the latching Shift button at the right of the front panel. Much as I dislike reviews based on an exhaustive tour of the front‑panel buttons and their functions, in the case of the MX2424, a look at the more important buttons is probably the best way to gain an understanding of the main functions of the machine and its operational philosophy.

<!‑‑image‑>All the main transport controls are large with status LEDs, which is sensible, although I felt that illuminated transport buttons would have appealed more to the professional user. An additional Rehearsal button initiates a rehearsal mode for any tracks that are selected as being ready to record. Both the fast forward and rewind buttons include a double‑push facility that sends the recorder to the end or start of the current 'project'. Holding down Stop while pressing fast forward or rewind moves the transport back or forwards through the song by the amount set for the Rollback value — which defaults to five seconds. Auto rehearse/recording is set by pushing the Shift key then either the Rehearse or Record key. The LED next to the appropriate key will then blink.

A hard disk recorder is of course capable of locating to any time position within milliseconds, but Tascam recognise that many users feel more comfortable with the dynamics of a traditional tape machine, so the behaviour of the fast forward and rewind buttons has been modelled on that of an open‑reel recorder. Progress through the audio file therefore accelerates once either button has been pressed, making it easy to 'wind' forward or backwards by small intervals of time, or use a fast 'wind' time when you need to travel faster through your recordings. For instantaneous access to any point within a song, the locate points are used. One hundred different location points can be set and these are stored when the unit is switched off.

At the left‑hand side of the panel, there are four track function buttons — All Safe/Auto Input, Record/Record All, Input Monitor/ All Input and Edit/Edit All — that relate to whichever tracks or tracks are selected (unless one of the 'All' options is used). When a track is selected for recording, a red section LED illuminates at the bottom of its bar‑graph meter, and when input monitoring is selected, a green bar shows at the top of the meter.

A further button just to the right of the track function section mounts or unmounts any SCSI media connected to the SCSI buss. It is recommended that SCSI drives are unmounted before powering down the system, though it seems that, as with most modern computers, failsafes are built in to ensure that the heads of connected hard drives are safely parked even in the event of a sudden power cut. To the right of this button is an important matrix of 20 status LEDs relating to sample rate, timecode, record mode and sync which provide a good overview of the operational status of the machine without the need to interrogate menus. Still further to the right is a row of six edit keys that are used when handling edits such as cut, copy and paste from the front panel (Undo and Redo are also found here). The section being edited is defined by the currently selected In and Out points (which are set from the buttons of the same name elsewhere on the front panel — more on these later).

The MX2424 can be used in a pseudo‑tape mode known as TL‑TapeMode where all recording, deleting and overdubbing is destructive. Undo is not available in this mode any more than it is on a real tape machine, but in the non‑destructive mode, up to 100 levels of Undo are available. So, you might ask, what's the benefit of using TL‑TapeMode? Well, if you're making live recordings or recording bands that don't need much in the way of editing, TL‑TapeMode is more straightforward and also makes more efficient use of disk space. For example, when you do a punch‑in, the old material is replaced just as it is with tape, not kept in case you need to use Undo. Non‑destructive mode, on the other hand, is useful when you have a lot of editing to do or when you may need to undo one or more stages of a process. As you may have guessed from this, TL‑TapeMode essentially works by creating one continuous audio file per track. Tracks recorded in this way are therefore easily imported into into a DAW, assuming it's compatible with one of the MX2424's file formats. Of course, if the DAW to which you're exporting supports the Open‑TL EDL format, this isn't a problem anyway, as the transfer will find all your audio files and copy them even if they're not stored on the MX2424 as contiguous files.

TL‑TapeMode can be switched off via the menus at any time during a session, which means that you could record a live gig or a set of backing tracks in TL‑TapeMode, then switch to non‑destructive mode for overdubs and editing. To go the other way, non‑destructive files have to be compiled into contiguous track files using the TapeMode Convert function before they can be worked on in TL‑TapeMode, but the process doesn't take long. There's also a similar function, Render, which creates a continuous audio file out of any section of audio with multiple edits that's located between the Edit In and Out points (as opposed to TapeMode Convert, which works on an entire project). This can be useful, because if a track has a huge number of edits, the performance of the recorder can eventually be compromised. Rendering provides an effective way around this problem and can sometimes recover wasted disk space by getting rid of unused sections of long sound files.

<!‑‑image‑>Moving to the control buttons directly above the transport section, the first of these is Online. When Online is selected, the machine will lock to whichever sync source has been selected in the setup menu. If the transport controls of an Online‑slaved MX2424 are operated while the machine is in this mode, it will come out of Online mode and resync to its internal clock source.

Loop initiates one of three possible loop functions as selected in the menu, and it operates around the currently selected In and Out points (see below). Loop mode may be used in conjunction with auto punch‑in, so you can keep attempting difficult‑to‑play sections. Pressing Shift/Loop causes the MX2424 to play back from the last position it entered Record or Play mode (this function is a dedicated key on the RC2424 remote), while pressing Loop and Locate together moves the playback position to before the In point, by an amount equal to the Pre‑roll time. Pressing the In or Out buttons alone causes the machine to locate directly to the In or Out points.

At the right of the front panel is a numeric keypad and above this, a two‑line, 20‑character LCD window. It may seem disappointingly small, but it is used mainly to show brief messages and time locations. The bottom line shows a timecode value that is used within the various positional functions of the machine, such as memory locations, In and Out points and offsets. Pressing the Capture button puts the current time position into the bottom line of the LCD, after which a further key‑press determines where that time value will be assigned — for example, to the In or Out points or one of the locators. Setting the In and Out values with the Capture key may be done when the recorder is in stop or while it is playing, but I nevertheless found the process unnecessarily involved, as you have to make four button presses to get the job done (Capture, then the In button, then Capture again, then the Out button). I do a lot of album editing using Sound Designer II and couldn't get by without some means of marking edit points on the flyusing a single keystroke. You can use the Shuttle/Scrub wheel to slow everything down a little, which makes inputting your edit points easier, but for me, the most satisfactory system remains one where where the crucial In and Out marking operations are consecutive, not separated by another button press. You can of course use the ViewNet software to do the job very precisely, though I think most people would agree that there are times when just working on the fly is fastest and most effective.

Up to 100 locate points can be set up per project using the Store key, which also doubles as an Enter key for some operations. Locators are called up using the Recall key, which also doubles as a No/Cancel button for destructive operations.

The Shuttle/Scrub Section

The two‑line LCD and locator buttons.

The two‑line LCD and locator buttons.

When enabled by the leftmost button in this section, the Shuttle/Scrub wheel's outer ring allows the user to vary the speed of forward or backwards play, while the inner ring is used to 'wind' the virtual tape forwards or backwards in time by small increments for the precise location of an edit point. Overall, the feel and quality of the Shuttle/Scrub function is excellent, and Tascam claim it will work to single‑sample accuracy with multiple machines, provided the MXs are connected using the TL‑bus. However, they were only able to supply me with one MX2424 for the review, so I wasn't able to test this claim.

One of the adjacent buttons, called Trim, changes the mode of the Shuttle/Scrub wheel such that the inner wheel or the Up/Down arrow keys, which are also positioned around the wheel, can be used to change the currently displayed timecode value or menu option at the bottom of the LCD. The outer ring moves the cursor from left to right in this mode. Pressing Trim again toggles back into conventional Shuttle/Scrub mode.

<!‑‑image‑>The Setup key accesses the menu of the same name, where global parameters are adjusted. Pressing Shift with this key will eventually give you access to a tempo map, but it's not yet implemented. The Proj button gets you to Track and Project management functions such as Load, Delete, Rename and so on. Using Shift with this button accesses the New function for the creation of new Projects. If you're in TL‑TapeMode, you also need to specify the length of the recording at this point. You can record past the stipulated end point (in theory up to the capacity of your chosen recording disk), but you can't start any recordings or punch‑ins after that time, so if you need to make the song longer, you should extend the length via this menu before continuing. Finally, View displays the contents of the selected track in the LCD window while Unload (accessed with Shift + View) unloads the track selected with the View key from the MX2424's playback track.

Using the MX2424

Before starting recording for the first time, the I/O configuration, sample rate and bit depth must be set, alongside any sync settings that are required if other devices are to act as sync master. Multiple setups (up to a total of 10) can be stored and recalled, which could be useful if in some situations you need to record via the analogue inputs and in others by the digital inputs, or if different sync scenarios are needed on a regular basis. After a suitable setup has been created or recalled, the next step is to create a new project. Projects can be named, and if a previous project is being continued in non‑destructive mode, the user can choose to load any of the original tracks or virtual tracks into the 24 physical tracks of the recorder. Alternatively, they can be left in their original position.

Once the machine is configured, recording proceeds very much as on a tape machine, although the transport is of course much quicker when you want to locate to specific locations. Punching in and out is fast and smooth with no obvious vices, but I feel that a separate large time display would have been useful. The ViewNet software does have a large time display, but you may not always wish to use the MX2424 with the computer switched on, especially while tracking.

While the operating system isn't in any way difficult to use, it isn't always intuitive, which means some operations may have you scratching you head the first time around. For example, using the Trim button to switch Shuttle/Scrub wheel modes for parameter adjustment isn't exactly obvious. Fortunately, everything is explained clearly in the manual — but we all know what musicians think about reading manuals!

Copying and pasting sections of audio is straightforward enough and involves bracketing the required section using the In and Out locators. Once copied to the clipboard, data can be moved, copied or inserted to a new In location on any track. The track select buttons are used to determine which tracks are being used as the source and destination for the edit. I have no complaints about the recording quality of the machine or about its ability to punch in and out smoothly, even when all tracks were being punched at the same time. Also, Tascam's claim that their engineers worked hard on the analogue converters seemed to be borne out — although the as‑yet unfinished 24/96 option really needs to be used to test these to their fullest extent, they did sound extremely transparent and smooth at 24/48kHz.

On a more practical note, the remote control doesn't include level metering other than clip LEDs, which either means keeping the recorder within view so you can see the meters there or making sure the meters agree with those on your mixer. This is fine if you have a digital mixer, but less easy to achieve using an analogue mixer. Of course, duplicating 24 meters wouldn't have been cheap, but Alesis managed it all right with their BRC. At the very least, couldn't metering have been included within the software? The main MX2424 box is fan‑cooled and makes about the same amount of noise as an average computer, so locating it at a distance from the recording environment would be desirable, which means in turn that the meters could easily be out of view.

Conclusions

At its present stage of development, it's probably best to consider the Tascam MX2424 as an enhanced tapeless replacement for a digital tape recorder than as an alternative to a full‑blown digital audio workstation, as it behaves in a smooth, reliable, tape‑like way while also offering comprehensive edit facilities that digital tape machines either can't do at all, or can only do slowly when multiple machines are used. At present, however, it doesn't offer as much in the way of detailed editing facilities as a computer‑based DAW. The ViewNet software offers quite a bit more editing than is possible from the front panel, though, and things should be improved when waveform editing support is added late this year (though the navigation tools are adequate, I like to be able to double‑check my cut points by seeing what the waveform is doing).

As mentioned earlier, I couldn't check the DVD backup functions, as no drive was fitted to the review model, although DVD seems a sensible choice, given its capacity and media cost. It's also very sensible that the backup routine is incremental, replacing only those parts of a session that have been changed since the last save. Having SCSI as standard is also useful for extending the recording time or making backups, and few people will quibble over the range of sync options.

From the post‑production point of view, a big advantage of the MX2424's Ethernet support is that all the machines in a multi‑room facility can be controlled from one computer, or from multiple computers depending on the user's requirements. Audio transfer via Ethernet is not yet implemented, but it's apparently under development and this should further endear the machine to professionals in the video post market.

From the project‑studio viewpoint, I feel Tascam would score more points with potential purchasers if they could come to an arrangement to have their hardware supported from within programs such as Logic or Cubase, where the on‑screen editing facilities are currently rather more comprehensive (integration with MIDI, more DSP functionality, waveform editing and so on). I know this isn't quite what Tascam planned for the machine, but being realistic, it is the way most project‑studio users would like to work. Perhaps this is something that may be explored in the future for those users who like their sequencer environments, but find computer‑hosted audio systems too limited?

If this isn't a direction that appeals to the design team, we may see another ADAT/DA88‑style divide between the Tascam MX2424 and the forthcoming Mackie HDR24/96, with one appealing mainly to pro studios and post‑production facilities and the other to project studios. Only the future will tell, but for the present, the Tascam MX2424 should satisfy anyone who wants to record multiple musicians with all the convenience of a tape recorder but with the ability to edit after the event.

On The Menus

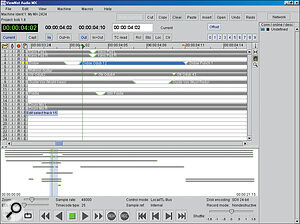

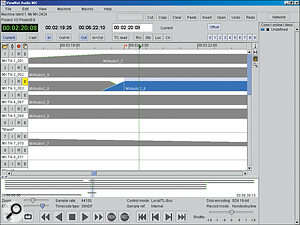

ViewNet in operation. The topmost part of the window shows a typical track display, which can be zoomed right in for fine‑detail editing (see the lower screenshot, where the view is zoomed right in to aid editing of a crossfade). The lower half of the window shows the Project overview.

ViewNet in operation. The topmost part of the window shows a typical track display, which can be zoomed right in for fine‑detail editing (see the lower screenshot, where the view is zoomed right in to aid editing of a crossfade). The lower half of the window shows the Project overview.There are 10 banks of menus within the MX2424 covering Rates and References, bus Controls, System Controls, MIDI, I/O, Audio Controls, Disk, Project and System. System is one of the first things that you need to access, because it's here that you set global parameters such as sample rate, I/O configuration, timecode chasing options, and so forth. There's also a varispeed function that provides up to ±12.5 percent of speed variation, though obviously, this is not available when the machine is in chase mode, as the speed will be set by the master sync source. Note too that although the MX2424 produces a digital clock based on incoming SMPTE sync, it doesn't do the same for MTC, as MTC is too imprecise to derive a reliable clock from. To avoid the possibility of timing drift when using MTC, it is recommended that the MX2424's clock should be locked to the clock of the device sending the MTC sync data via word clock. For use with a music sequencer, it would make sense in most situations to use the MX2424 as the master, then use MTC to sync the sequencer. Used like this, there shouldn't be a problem, but when the MX2424 is in Slave mode and only MTC is available (in other words, if you are unable to derive a word clock output from the sequencer), the manual rightly points out that the timing could drift over time. This is not a fault of the Tascam machine but a limitation of MTC and will apply to any machines trying to lock by this method. Still, it's better to have the MTC option than not, and with shorter projects, timing is unlikely to be a problem.

All common frame rates are supported including 29.97 drop and non‑drop frame and 30 drop and non‑drop frame. The machine will automatically detect the correct frame rate if it is 24, 25 or 30fps, but as with most systems, it won't automatically recognise drop frame. The clock source for the MX2424 can be set to internal or to follow any of the incoming digital sync sources or word clock. Internal sample rates supported are 44.056kHz, 44.1kHz, 41.44kHz, 47.952kHz, 48kHz and 48.048kHz. The default setting is 44.1kHz. Default real‑time audio crossfade lengths between edits are set globally, also via the menu system with 10mS being the default. This is purely to avoid clicks and glitches at edit points; the maximum crossfade time available is 90mS. The Disk Settings section selects the audio file format type and also the recording bit depth.

The Disk menus also handle formatting attached SCSI drives, displaying free disk space, recovering free disk space, backing up projects and so forth. Various parameters associated with using the MX2424 on a computer network are also accessed here.

Using ViewNet To Edit Your Tracks

<!‑‑image‑>PC hardware requirements for ViewNet are a 1024x768 display, PC Pentium 400 (or higher), and Windows 95/98 or NT. Mac users need a Power PC, G3 or G4 running OS 8.5.1 or later. Connecting a PC via Ethernet and setting up the software was fairly straightforward, and though I didn't have multiple machines to try, networking the machines is a possibility. Audio tracks are visible as graphic bars rather than as waveforms, as on the original Otari RADAR display, and cuts in the audio are indicated by green lines. The view may be zoomed in or out allowing an area of interest to be viewed with more precision, though waveform views are not yet available (waveform editing is planned as an update due before the end of the year). Sections of audio may be deleted, copied, moved and pasted as well as reversed, and there's provision to crossfade between sections, with a choice of 10, 11, 13, 15, 18, 22, 30, 45 or 90 millisecond fade lengths to smooth transitions between regions. More comprehensive fade tools are available within ViewNet.

<!‑‑image‑>Existing fade times may be changed to any value by dragging using mouse and key combinations, and a separate key combination is provided to adjust the level of one end of a region while leaving the other as it was, in effect creating a region‑length fade in or out. A small tool palette simplifies on‑screen operations and tracks/regions may be dragged, copied or changed in length very quickly. The lower part of the screen shows all the tracks for the entire length of the project while the upper part of the window can be zoomed in to any horizontal or vertical resolution. Region positions may be nudged in preset fine or coarse increments, which makes getting the timing right between regions fairly easy, and it's possible to use the In and Out points to loop around the section being adjusted.

Considering the current lack of waveform view, navigation is pretty straightforward, and if a section of the song is highlighted in the overview window, the upper window automatically zooms to display the selected section. Having a reverse playback function is also useful for double‑checking edit points. Many of the transport keystrokes are somewhat non‑standard compared to other sequencers or DAWs, with the arrow keys being used to start and stop playback rather than the more commonly used space bar (a consequence of the Java programming), but fortunately, the key commands take very little getting used to once you know what they are.

There's no way to lock stereo pairs of tracks for editing — instead, you have to select multiple tracks for editing after which cuts or moves are duplicated for both parts. There's also no way to solo tracks, which could make setting difficult edit points easier. Playback can be controlled either from the computer keyboard, from the front panel or from the remote control unit if one is fitted. Virtual transport buttons are also provided within the software and reverse playback is possible as well as forward. There's no on‑screen audio scrubbing, but if the front panel or remote Shuttle/Scrub wheels are used for this purpose, the ViewNet cursor position follows the progress through the audio file, making this another possibility for pinning down edit points.

Macros

Computer users will be familiar with the concept of macros, where one keypress or key combination can set in motion a pre‑programmed chain of commands. The RC2424 remote controller, which is otherwise very similar to the front panel of the MX2424, has eight Macro keys, each of which can be programmed with sequences of up to 99 keystrokes. If a Macro key is held down for longer than one second, it goes into Macro Record mode and all subsequent button presses until the next press of the same Macro key will be recorded. Briefly pressing the Macro key plays back the Macro. If you're doing any kind of repetitive task, these Macros can save a lot of work.

Keeping Up — OS Software Updates

At present, upgrades to the MX2424's Operating System are made via the SmartMedia slot on the right‑hand side of the front panel. As upgrades appear, they will be posted as downloadable files on the Tascam web site. Of course, you still need some way of getting the file onto a SmartMedia card (one card is supplied free of charge), which is fine if you own a laptop with a SmartMedia slot built in, but not so useful if you have a desktop computer with no SmartMedia compatibility. Tascam say that it's possible to use the ViewNet software to port OS updater files from a computer to the MX2424 via the Ethernet connection, but as no upgrade files were ready to test this with at the time of the review, I wasn't able to confirm this myself. However, Tascam say their dealers will put upgrades onto your SmartMedia card for you, so one way or another, upgrading shouldn't be too painful!

Options & Pricing

- MX2424 — £2999

The basic unit.

- RC2424 — £1155

The Remote control, which duplicates the front‑panel controls of the MX2424 with additional keys for easier editing and for controlling multiple machines via TL‑Sync.

- IF AN24 — £1155

24 channels of 24‑bit analogue I/O at balanced (+4) line level on three 'D'‑sub connectors, fitting into a different bay to the digital I/O options.

- IF AE24 — £745

24 channels of AES‑EBU digital I/O arranged as 12 stereo pairs available via three 'D'‑sub connectors, with input sample‑rate conversion.

- IF AD24 — £385

24 channels of ADAT digital I/O via three pairs of lightpipe connectors.

- IF TD24 — £385

24 channels of TDIF I/O via three 'D'‑sub connectors.

- HITACHI/PANASONIC DVD‑RAM DRIVES £TBC

5.25Gb capacity, equating to around 25 minutes of storage for 24 tracks.

- SEAGATE TREVAN TAPE DRIVES — £TBC

10Gb capacity, equating to 45 minutes of storage for 24 tracks.

The above options are available from Tascam dealers. All prices include VAT.

Pros

- Excellent recording quality with particularly good analogue converters.

- Effective tapeless tape recorder emulation.

- Smooth Shuttle/Scrub controls.

- Comprehensive choice of interfaces and sync options.

- Good range of I/O options.

- File format compatibility.

Cons

- Operating system not always intuitive.

- Computer editing software currently doesn't offer waveform‑level editing.

- No large time display on the hardware.

- No level metering on remote control.

Summary

Twenty‑four tracks of very high‑quality tape‑style recording without all the limitations of tape. The editing functions are less comprehensive than those of a full‑blown DAW, but they offer all the essentials, including gain changes and fades, in a manageable format.