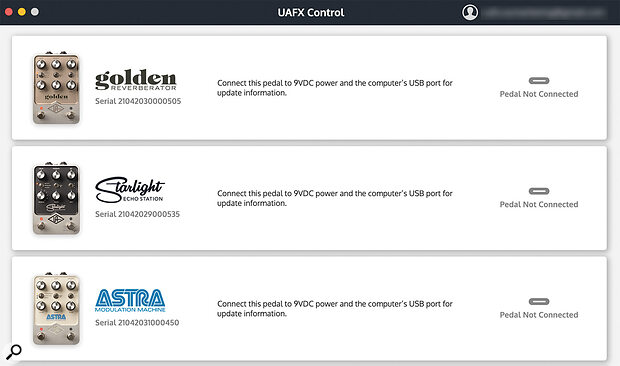

UA have long been among the best developers of analogue‑modelling software, so the world is expecting great things of these little boxes. Do they deliver the goods?

Universal Audio signalled their intention to enter the guitarist’s hardware world in 2017, when they announced the OX Amp Top Box, and they’ve now released a set of conventional stompboxes, comprising a modulation effects unit, a delay and a reverb. All three share the same aluminium cases that slope gently down toward you, and are somewhat larger than typical pedals. They also share the same hardware, with only minor differences: two‑ or three‑position ‘variation’ switches, depending upon the unit, a two‑position mode switch on the Starlight where the Astra and Golden have modulation knobs, and a six‑position clock divider/ping‑pong selector on the Starlight, where the Astra and Golden have tone controls. Other than that, the only visible differences are their colours and silk screening. Ah yes… the silk screening. When I was reviewing the units in my studio I didn’t give this a moment’s thought because it’s well lit and the legends, while small, are clean and smart. But when I took them to my dungeon with the dim lighting and the big amps I found myself struggling to see what was what.

Inevitably, all three pedals also share many less visible features, including ARM‑powered processors that, unlike earlier generations of modelling pedals, are capable of running unadulterated mathematical models at high resolution rather than the approximations that were previously necessary. On the other hand, each offers but a single preset memory, and this is bound to cause controversy.

The Astra

As supplied from the factory, the Astra Modulation Machine hosts three emulations. The first of these, Chorus Brigade, recreates the sound of the Boss CE‑1 Chorus Ensemble, and the only difference between the original and the emulation lies in a second output mode on the UA pedal. When using both outputs of a CE‑1, the original signal appears on one and the processed signal on the other. The Astra emulates this in its Classic mode but, in Dual Stereo mode, a single input is split into two, both sides are processed, and the results are then sent to the two outputs 90 degrees out of phase from one another. The result is a classy swirl that can’t be obtained from the original. I compared the Astra with my original CE‑1 and found the two to be very similar although, for any given rate, the chorus depth of the Astra is deeper. Do I care? In truth, not at all. The Astra sounds great, and who’s to say that a second CE‑1 would sound exactly the same as mine? I doubt that it would.

The Astra Modulation Machine.The next model emulates the MXR Model 126 Flanger/Doubler. UA have already cloned this as a plug‑in and, while the Astra doesn’t have the same layout, all of its controls and switches are present and correct. However, whereas the original was a single‑channel device, the Astra can also offer wide stereo effects — these may not be authentic, but they’re very nice. What’s more, and like the Chorus Brigade, you can control the modulation rate using tap tempo, which is another bonus. Or rather, it would be if this facility were available using the factory settings. Unfortunately, you can only obtain it after modifying a hidden setting using the UAFX mobile app, which was still in development at the time of review. I can’t imagine what UA’s designers were smoking when they made that decision.

The Astra Modulation Machine.The next model emulates the MXR Model 126 Flanger/Doubler. UA have already cloned this as a plug‑in and, while the Astra doesn’t have the same layout, all of its controls and switches are present and correct. However, whereas the original was a single‑channel device, the Astra can also offer wide stereo effects — these may not be authentic, but they’re very nice. What’s more, and like the Chorus Brigade, you can control the modulation rate using tap tempo, which is another bonus. Or rather, it would be if this facility were available using the factory settings. Unfortunately, you can only obtain it after modifying a hidden setting using the UAFX mobile app, which was still in development at the time of review. I can’t imagine what UA’s designers were smoking when they made that decision.

The third of the factory‑loaded models is a tremolo derived from the misnamed vibrato of mid‑1960s Fender amps such as the Deluxe Reverb. However, while the relationship between faster rates and lesser depth has been faithfully modelled, as has the way that the vibrato ducks when you play loudly and then becomes more apparent as the note decays, you can now choose between the original sine wave and a square wave modulator, tweak the LFO shape, and select stereo panning on each sweep. Given the classic sound of the original, I didn’t expect to like these extensions as much as I did. But I did.

When you register the Astra, two additional emulations become available. The first of these recreates the sound of two generations of the MXR Phase 90 — the ‘script’ (1974) and ‘block’ (late‑’70s) versions, with their different feedback amounts and rate ranges. They’re still capable of the subtle single‑channel swirl that distinguished the Phase 90 from much of its competition but UA have also added a stereo mode that inverts the left channel with respect to the right, and an input drive to increase the harmonic content. Had they chosen to go the whole hog, they could have emulated the Phase 100, using the (currently redundant) intensity knob to select the larger unit’s four depth and width settings. (I wish that they had, because an electronic piano played through a Phase 100 is one of the great sounds of the 1970s.)

The final emulation was inspired by the vibratos in the Fender Brownface and Blonde amps from 1961. Called the Dharma Trem 61, it’s a gem. To generate the effect, the signal is split into bass and treble bands to which vibrato is applied with opposite polarities before being summed back to mono. UA describes the result as a tremolo that has both volume and phase‑like components. You can control the crossover frequency and panning of the output, and select from two processing modes called Classic and Vibey. In addition, the modulation rate is amplitude‑sensitive, so you can set a volume threshold above which it speeds up (or slows down) from the initial rate to a second rate, and below which it drops back down (or rises back up) to the initial rate. The quality of effects that you can obtain is stunning. If Don Leslie had been designing for guitarists, I reckon that this is the effect that he would have invented.

The Starlight

There are again three factory emulations in the Starlight Echo Station, but this time there’s only one downloadable addition. The first, Tape EP‑III, is a recreation of the solid‑state Echoplex EP3 used by the likes of Jimmy Page and Brian May. Apart from the dedicated echo/sound‑on‑sound control of the original, all of its controls are recreated, and the EP‑III also adds a parameter to determine the amount of wow and flutter present as well as the prominence of the tape splice. There are three EP3 variations available, and these boil down to mint, used, and in desperate need of a service. Whichever variation I chose, I liked the increasing distortion as the echoes regenerated, the chorusing generated by the wow and flutter, and the ability to push the feedback gain beyond unity to create infinite oscillation. But I wonder who would want the tape splice to be as obvious as it can be when the Mod setting is turned toward its maximum.

The Starlight echo/delay pedal models a number of revered analogue units.Next comes Analog DMM, a recreation of the Electro‑Harmonix Deluxe Memory Man that was designed using a mélange of the best traits from several vintage units. Again, the Starlight duplicates the controls and character of the original, but with one significant difference. When you use both outputs on a Deluxe Memory Man, the input signal passes from one and the echoes from the other. The Starlight doesn’t emulate this; both outputs are always ‘wet’. I have an original Deluxe Memory Man (the original original, not a reissue) so I compared the two. The Starlight scored highly although, as with my comparisons of the CE‑1, the emulation wasn’t always identical. That said, unless you have a 45‑year‑old original to hand, it’s unlikely that you’ll ever know the difference.

The Starlight echo/delay pedal models a number of revered analogue units.Next comes Analog DMM, a recreation of the Electro‑Harmonix Deluxe Memory Man that was designed using a mélange of the best traits from several vintage units. Again, the Starlight duplicates the controls and character of the original, but with one significant difference. When you use both outputs on a Deluxe Memory Man, the input signal passes from one and the echoes from the other. The Starlight doesn’t emulate this; both outputs are always ‘wet’. I have an original Deluxe Memory Man (the original original, not a reissue) so I compared the two. The Starlight scored highly although, as with my comparisons of the CE‑1, the emulation wasn’t always identical. That said, unless you have a 45‑year‑old original to hand, it’s unlikely that you’ll ever know the difference.

Before moving on, I have to mention the preamp coloration parameter available for these two models. This coloration is an important characteristic of both but, I hear you ask, “what coloration setting?”. Unfortunately, this is again available only via the mobile app, which is a shame because switching it on makes a considerable difference in both tone and amplitude, and I could see you wanting to switch between off and on during performance. At least the factory default for the Starlight’s right footswitch is preset+tap (it acts as a tap when you press and release it quickly, and as a preset on/off when you press and hold it) which is an improvement over the Astra.

The third model is based upon UAD’s Precision Delay Modulator, an unapologetic digital delay with no virtual analogue distortion, coloration or wobbliness. What it has instead is the ability to modulate the delay path with either chorus of flanging. The amount of control that you have over this is limited; a single knob acts as a macro, combining the rate, depth, feedback amount and mix of modulation, but it nonetheless proves to be particularly musical when using the ping‑pong modes. And, while the maximum feedback gain is unity (which means that you can have infinite delays) it never goes into self‑oscillation, so sound‑on‑sound is a doddle. While not as sophisticated as many digital delays, it can be a source of many top‑notch ‘clean’ effects.

The bonus emulation is called the Cooper Time Cube and is based upon a Heath Robinson delay line made from lengths of garden hose! I can’t vouch for the authenticity of the sound but, while the algorithm may be inspired by the original, it isn’t a slavish recreation of it, not least because its maximum delay time of 2500ms equates to a hose length of nearly 3,000 feet. (The original had two lengths of just 16ft and 18ft, and a maximum delay of 30ms if you connected them in series.) But while its premise and controls are the simplest of the Starlight’s models I found that I kept coming back to it. For simple delays and sound‑on‑sound, it has a quality that I really like. Given what else is on offer here, that’s a serious accolade.

The Golden

The last pedal provides reverb effects based upon several mid‑1960s Fender springs, three EMT plates, and three digital reverb algorithms from the Lexicon 224.

The Golden: a range of spring, plate and Lexicon reverbs.The first, Spring 65 offers three variations based upon three tanks selected for their qualities and differences. You select the tank using the decay control, with each offering a different but fixed time, and there are then three further variations for each; bright and snappy, smoother, and a third with a longer decay. You can apply pre‑delay to any of them, and equalise the reverb with fixed‑frequency bass and treble shelves. Reverb modulation (wow applied at low settings and both wow and flutter at higher ones) is derived from the EP‑III and, while it isn’t authentic, you’re going to like it. In fact, I can’t imagine you not liking Spring 65 because it clangs, boings and distorts in a fashion that’s far superior to many other spring emulations that I’ve heard.

The Golden: a range of spring, plate and Lexicon reverbs.The first, Spring 65 offers three variations based upon three tanks selected for their qualities and differences. You select the tank using the decay control, with each offering a different but fixed time, and there are then three further variations for each; bright and snappy, smoother, and a third with a longer decay. You can apply pre‑delay to any of them, and equalise the reverb with fixed‑frequency bass and treble shelves. Reverb modulation (wow applied at low settings and both wow and flutter at higher ones) is derived from the EP‑III and, while it isn’t authentic, you’re going to like it. In fact, I can’t imagine you not liking Spring 65 because it clangs, boings and distorts in a fashion that’s far superior to many other spring emulations that I’ve heard.

Next come three plate reverb emulations based upon three EMT 140s described as: older, shorter and brighter; older, longer and darker; and newer, longer, flatter, and with a warble. Their EQ is more powerful than the 65’s, but I found their reverb modulation to be very subtle. I wondered whether I was missing something until I read the manual, which explained that this “subtly increases dispersion and reduces ringing”, so I cancelled my call to my otolaryngologist and carried on experimenting. All three are warm and enveloping but, if I had to choose a favourite, it would be the second one. They’re all very good, though, so please feel to disagree with me.

Finally, we come to the three Lexicon 224 models, one installed at the factory and the other two available once registered. Having licensed the original algorithms many years ago, UA have been offering a 224 plug‑in for the past decade, marrying their own emulations of the input stages and the converters of the time with the 224’s slightly grainy processing. Six variations are available on the Golden, all drawn from the original device: Room A, Small Concert Hall A, Large Concert Hall B, Percussion Plate A, Constant Density Plate A, and Acoustic Chamber. For obvious reasons, these are very accurate recreations, to the extent that you can obtain the Lexicon’s (usually unwanted) self‑oscillation in the tails of long decays. While this is authentic and fun to use as an occasional special effect, you’ll probably want to dial things back a bit if it occurs. But how do the variations sound? In a word, wonderful. I don’t think that there was a single line or chord that I played during these tests that didn’t sound better when played through one of them, especially with a touch of reverb modulation dialled in. I can’t claim to have heard every reverb pedal on the market but, despite its paucity of controls when compared with some of the larger units available, this is the reverb pedal that I would come back to every time. What more can I say?

Unless you have a 45‑year‑old original to hand, it’s unlikely that you’ll ever know the difference.

Further Thoughts

Thanks to their ability to handle line levels, I was also able to try all three UAFX pedals with active and passive basses and a number of keyboards as well as guitar. Back in the 1970s, I used an EHX Small Stone to enliven my string synths, a Boss CE‑1 to add character to my RMI piano, plus a Pearl BBD echo/reverb for delay effects on my mono synths, and the UAFX pedals replace and exceed these in every way. Sure, there’s nothing off‑the‑wall or unexpected about the sounds that they create, but placing a suitable overdrive in front of all three UAFXs will create a pedalboard that’s easy to understand and will sound, without exception, superb. I suppose that some might claim that they’re too quiet to fool the cognoscenti but, given the years I spent trying to control analogue noise, I welcome virtual silence with open arms. Furthermore, the dual processing engines in each pedal allow you to switch between their live and preset modes without an unnatural break in the sound; for example, the tail of a long reverb will decay naturally when you switch to a shorter one.

Oh yes… and while they take around 15 seconds to boot, they continue to pass the unadulterated analogue input signal during that time, as they will if they lose power. Happily, there are no nasty thumps when power is lost, and just a slight click when it comes back.

Nevertheless, there are some design decisions that I would have made differently. For example, I would have liked to find external synchronisation on the Astra and Starlight. Lots of bands play to click tracks and, without a clock input or even a delay time readout on the pedal, it’s going to be very difficult to lock to the song tempo. Ducking would also have been nice on the Starlight, as would expression pedal inputs and MIDI on all three. But when I discussed this with the chaps at UA, they reminded me that the philosophy behind the product line had been to keep them as simple and as analogue‑feeling as possible: no displays, no page diving, no complex setups or MIDI. It’s a valid approach, but I suppose that their sound quality makes me want to take things further. Perhaps the USB socket could allow for some developments in this area, so let’s keep our fingers crossed.

Another area that could be improved is the manuals, each of which is supplied on UA’s website as an article, not as a PDF file. The marketing department seem to have been given access to these, which is always a mistake in my view, but I still recommend that you download them because, despite the sometimes‑flowery language, they contain valuable information.

The biggest change that I would make, though, would be to sell each of the pedals with a power supply, since there’s no internal battery option. I know that many guitarists have pedalboards with spare power connectors and won’t want unused PSUs lying around, but I can also see many happy faces turning to sad ones when purchasers open their exciting new boxes and realise that they needed to (and didn’t) buy one.

Final Thoughts

Cramming all three of these pedals into a single review does them little justice, and I would have loved to describe them in much greater detail, not least because I have been impressed with all of them. So… should you be interested? If you need things such as memories to step through a live set, timing readouts, synchronisation, expression pedal inputs, or automation, I’m sad to say that you’ll currently have to look elsewhere. But if you use your stompboxes in the traditional manner, I don’t think that I’ve ever heard better.

Rear Panels

Round the back of each pedal you’ll find a pair of quarter‑inch TS (unbalanced) inputs, a pair of quarter‑inch TS (unbalanced) outputs, a 400mA 9V DC power input socket and a USB‑C socket for updates. I was surprised to find that, like the control knobs, the inputs and outputs are plastic. Metal would have felt more professional, and would have been appropriate at this price. Furthermore, if you power the pedals using right‑angled 9V connectors (as are common on many pedalboards) these can obscure the USB socket. The final bit of hardware on the rear panel of each is a button that pairs the pedal with another Bluetooth v5 device so that they can talk to the mobile app.

If you confine yourself to a single input and output, you have a traditional single‑channel signal path, but this would be a waste because a single input directed to both outputs offers all of the spatial goodness that these pedals can provide. In addition, each also offers true stereo effects with two independent signal paths (but common parameters) if you use both inputs and both outputs.

Bypass Modes

Each pedal has its own screen in the mobile app, and these offer the bypass routing parameter, plus preamp coloration on/off on the Starlight, and the right footswitch mode (preset/tap/preset+tap) on the Astra and the Starlight. I tested a pre‑release ‘beta’ version using an iOS device and it installed and worked first time.

Each pedal has its own screen in the mobile app, and these offer the bypass routing parameter, plus preamp coloration on/off on the Starlight, and the right footswitch mode (preset/tap/preset+tap) on the Astra and the Starlight. I tested a pre‑release ‘beta’ version using an iOS device and it installed and worked first time.

You need the UAFX Control mobile app to determine which form of bypass is enabled. True bypass is the factory setting, and this kills the processed signal instantly when you tread on the left‑hand footswitch. In contrast, the Buffered (Astra) and Trails (Starlight and Golden) modes stop any new signal from entering the signal path but allow anything already in them to reach the outputs in the normal way. It would seem much more sensible to me to have had the buffered bypass as the default.

Pricing Considerations

Some people have already criticised the UAFX range for what they perceive as high prices but, not to put too fine a point on it, I think that they’re bonkers because state‑of‑the‑art pedals have never been more affordable. What’s more, replacing my CE‑1 would currently cost somewhere between £500 and £700 (about $700‑1000), replacing my Deluxe Memory Man would cost closer to £750 ($1060) and, at the time of writing, a Lexicon 224 is on sale here in the UK for £2,500. Even if these were the only effects that I wanted to recreate, the UAFX pedals would be excellent value. Given everything else that they offer and the quality with which they do it, I think that their prices are more than reasonable.

Pros

- The sounds of all three are, without exception, as good as (or better than) anything that I’ve ever heard emanating from a pedal.

- They feel solid and robust, tough enough for life on the road.

- It’s simple to obtain great effects — in fact, it’s almost impossible to obtain bad ones.

Cons

- Some parameters can only be accessed via a mobile app.

- You can only store one preset.

- No expression pedal input, synchronisation or automation.

- Power supply required but not included.

- Clearer legends would be welcome.

Summary

Normally, a list of several ‘cons’ would suggest that you should avoid a product. Not this time! While there’s an ever‑increasing range of high‑quality competition, it’s almost impossible to obtain an uninspiring sound from any of the UAFX pedals, and I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend that you check them out. You’re going to be impressed.