I've never known what the difference is between a passive EQ and an active one. Could you explain?

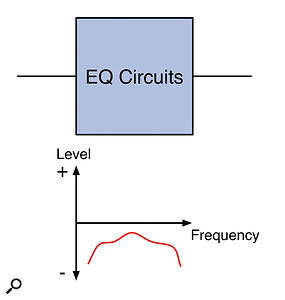

Passive EQ: A simple cut-only EQ can be made with passive components, but will reduce the level and potentially degrade the quality of the audio.

Passive EQ: A simple cut-only EQ can be made with passive components, but will reduce the level and potentially degrade the quality of the audio.

SOS Forum Post

Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: In terms of the raw circuit elements involved, the answer is 'not much'. But the way in which those circuit components are used is radically different between passive and active equalisers.

Most forms of audio equalisation are inherently 'lossy' processes in terms of signal level, and simple filter circuits are actually frequency-selective attenuators; they reduce the signal level above or below a frequency determined by the component values. So if you want to make a simple cut-only equaliser (as shown in the top diagram, right), it can be done quite easily with purely passive components (capacitors, inductors and resistors), all carefully chosen to provide the desired turnover frequencies and slopes. With this kind of design, power is not needed at all, but the type of equalisation that can be achieved is limited to simple high- and low-pass filters, and basic band-pass filters with gentle slopes.

The loss of signal level through a purely passive filter stage is often undesirable, and the turnover frequencies and slopes may be affected by the impedances of the source and destination equipment. For these reasons it is common practice to incorporate transformers and buffering amplifiers to help guarantee consistent performance, and to compensate for losses through the filters. In this case, although the equalisation itself is still passive, power will be required for the amplifiers that are present in the circuit.

Buffered EQ: Introducing a buffer amplifier post-EQ can make up for the lost level.

Buffered EQ: Introducing a buffer amplifier post-EQ can make up for the lost level. With an amplifier in the box, it obviously becomes easy to introduce gain, and that allows the design to be configured to boost frequencies as well as to cut them (as shown in the bottom diagram, below). This is achieved in a 'passive' design by configuring the filters to have a fixed loss across all frequencies in their default 'flat position', and this broad-band attenuation is compensated for by the buffer amplifier. To introduce a frequency boost, what you do is reduce the amount of attenuation through the filter at the desired boost frequency, such that the gain in the overall system turns that into a frequency boost. Many classic vintage equalisers were designed to operate in this way, and there are a great many advocates of this approach, arguing that it has sonic benefits.

The more modern approach, though, is to incorporate the equaliser components within the negative feedback loop of the amplifier itself (see the diagram, right). Negative feedback around an amplifier circuit has been used since the late 1920s to help reduce distortion and unwanted non-linearities, but it can also be used to introduce specific frequency responses in a very controlled and predictable way. This is standard practice in every commercial mixing console and most modern outboard equalisers of every kind, and it affords a great deal of flexibility and sophistication in the performance of the equaliser. The adjustable bandwidth (or Q) of parametric equalisers is really only achievable in a practical way using active techniques.

Feedback EQ: Incorporating the EQ circuitry into the negative feedback loop of the amplifier is a common approach to modern active EQ designs. However, the complications that are involved with the design can degrade the output signal.

Feedback EQ: Incorporating the EQ circuitry into the negative feedback loop of the amplifier is a common approach to modern active EQ designs. However, the complications that are involved with the design can degrade the output signal.One of the most important advantages of this approach is that gain is only introduced when the EQ settings demand it: there is no overall gain involved all the time, as there is in the buffered equaliser design mentioned earlier. That makes the design less noisy and improves the headroom margin.

As we all know, though, there is no such thing as a free lunch, and there are some potential issues relating to feedback equalisation. These include gain-bandwidth restrictions, limited slew rates (the maximum rate of change of the circuit's output voltage) and phase-response anomalies, all of which are dependent on the amplifier design itself. However, a competent designer using good-quality components can easily render all of these utterly insignificant for audio applications. Even so, some audiophiles cite these issues as reasons for preferring the simpler passive approaches.