We show you that if you put enough effort into the musical arrangement and get the editing out of the way at the start, the mix itself isn't that difficult!

The Free Radicals are a three-piece band comprising Damien Foran (lead guitar), Alan Corcoran (bass, drum programming), and Richard Jackson (guitars, vocals). They are based in Wexford, Southern Ireland, and have been on the song-writer circuit there since forming two years ago. What started as a hobby has evolved into something more serious, and they are now recording and producing tracks for future release. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I end up talking a lot about processing, effects and automation in the Mix Rescue column, but there's often much more to creating a successful mix than tweaking plug-in parameters. For a start, the musical arrangement has a large role to play — if your instrumentation thins out at the wrong moments, there's little that processing can do to compensate for this. There's also the issue of timing and tuning, which, if denied the proper attention at the tracking stage, can undermine the momentum of the track as a whole and render even a great arrangement very difficult to blend together. And if you're trying to simulate live performers with MIDI parts, you need to really concentrate on the programming details to make these sound musical in context, or else they're always going to feel rather 'stuck on'.

The Free Radicals are a three-piece band comprising Damien Foran (lead guitar), Alan Corcoran (bass, drum programming), and Richard Jackson (guitars, vocals). They are based in Wexford, Southern Ireland, and have been on the song-writer circuit there since forming two years ago. What started as a hobby has evolved into something more serious, and they are now recording and producing tracks for future release. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I end up talking a lot about processing, effects and automation in the Mix Rescue column, but there's often much more to creating a successful mix than tweaking plug-in parameters. For a start, the musical arrangement has a large role to play — if your instrumentation thins out at the wrong moments, there's little that processing can do to compensate for this. There's also the issue of timing and tuning, which, if denied the proper attention at the tracking stage, can undermine the momentum of the track as a whole and render even a great arrangement very difficult to blend together. And if you're trying to simulate live performers with MIDI parts, you need to really concentrate on the programming details to make these sound musical in context, or else they're always going to feel rather 'stuck on'.

This month's track, 'Fly Away' by the Free Radicals, was a case in point. The band had recorded guitars, bass, and vocals alongside a drum part running from Steinberg's Groove Agent, and this had been mixed down by the band's frontman and recording/mixing engineer elect Richard Jackson, who was unhappy with the sound, but wasn't really sure what was letting him down. Was it the band's instruments that weren't up to the mark? The recording quality? The mixing techniques? The home-studio setup?

While it was clear on listening to Richard's mix that all of these areas could do with some improvement, it was also apparent that the real roots of his problem were that the guitar arrangement needed some extra support and that many of the parts were fighting with each other in terms of the timing and tuning. I asked Richard to send over his multitrack files, and these highlighted further problems. Firstly, the drums were mixed to mono and were also phasing in a rather unnatural way, perhaps from layering of two similar drum patterns together; and secondly, there weren't enough guitar parts actually recorded to give me any scope to develop the arrangement further. So I suggested that Richard redo the drum parts, perhaps with some kind of multitrack drum instrument (to provide a few more mixing options) as well as working on some additional guitar layers to flesh out the arrangement.

Editing Bass & Guitars

A little while later Richard sent me a new set of audio files, this time with multitrack drums courtesy of XLN Audio's Addictive Drums software instrument. A quick listen to the new drums confirmed that the phasing problems were history, but before I got into any proper mixing I put together a simple rough balance of the drums and began work on tidying up some of the timing and tuning, as well as developing the arrangement a little. This kind of more technical work can really disturb the flow of the more artistic mixing process, so I always like to try and get it out of the way early on. (Judging by the mix engineers interviewed in our Inside Track series, I'm not the only one who likes to scotch the editing early on. I just wish I also had an army of assistants on hand to do it for me...)

Re-ordering the tracks in Cubase's Project window to place the bass and kick-drum parts adjacent made it possible to tighten up the bass part's timing almost entirely visually, which made it much quicker to do. Nevertheless, all the edits were still auditioned to confirm that what looked sensible actually sounded right.First up was the bass part, which was actually quite tightly played most of the time, although a few moments during the introduction and the lead-in to the final chorus needed some adjustment. This was a doddle to do, as I could just place the bass track next to the kick-drum track and then pretty much edit by eye. There's no substitute for listening, though, when you're checking timing edits, so you should always confirm that an edit sounds right: the more you do this kind of editing, the more you come to realise that what looks right sometimes sounds wrong, and vice versa. (The pre-chorus lead-in section also had a few little audio glitches, but a bit of copying and pasting removed these in next to no time.)

Re-ordering the tracks in Cubase's Project window to place the bass and kick-drum parts adjacent made it possible to tighten up the bass part's timing almost entirely visually, which made it much quicker to do. Nevertheless, all the edits were still auditioned to confirm that what looked sensible actually sounded right.First up was the bass part, which was actually quite tightly played most of the time, although a few moments during the introduction and the lead-in to the final chorus needed some adjustment. This was a doddle to do, as I could just place the bass track next to the kick-drum track and then pretty much edit by eye. There's no substitute for listening, though, when you're checking timing edits, so you should always confirm that an edit sounds right: the more you do this kind of editing, the more you come to realise that what looks right sometimes sounds wrong, and vice versa. (The pre-chorus lead-in section also had a few little audio glitches, but a bit of copying and pasting removed these in next to no time.)

It's worth mentioning as a general tip that the effectiveness of timing edits is much easier to judge if you listen with enough context. In other words, make sure you listen across the edit from at least four bars before the edit point, because your own internal musical pulse needs enough time to firmly latch onto the track's groove if you're going to sense the small 'stumbling' sensations that tell you that you still have work to do.

Guitar parts followed, and all of them benefited to some extent from being edited to more closely match the drum timing. I wanted to pan the main pair of chorus rhythm guitars left and right to give some width to the stereo field, but when you do this any timing discrepancies between the two parts become much more obvious and distracting, so these needed particular care. The way I approached the task was first to edit one of the two parts to match the drums, and then to edit the second part to line up with that. The advantage of this way of working is that if something sounds out of time, you always know which guitar part is likely to be the culprit. It's much trickier to distinguish between the two parts if you're correcting the timing of both at the same time, and I find it takes much longer to finish the job that way.

While I was correcting the various bits of timing, it occurred to me that many of the guitar parts were made up of repeating riffs, and that I could probably conjure up a few extra double-tracks by copying and pasting these repeated sections into different positions. This proved fairly quick to do, and helped make the overall guitar sound feel a bit more 'full' and 'produced' in a way that I figured would appeal to Richard and the band, given that they'd referenced mainstream bands like the Stereophonics and Snow Patrol in their communications with me. Again, though, the timing between the two sides of the stereo image had to be kept quite tight in order to avoid any stereo ping-ponging of the guitar chords.

Copying and pasting sections of a single rhythm-guitar part allowed a second part to be created, allowing the pair of tracks to be opposition-panned for a nice stereo effect. However, this necessitated careful editing to avoid timing discrepancies between the two tracks resulting in distracting stereo ricochets.The guitar and bass parts were easy enough to deal with using nothing more fancy than Cubase's normal Project window facilities. The edits for the guitar parts were very easy indeed, simply because the distorted timbres hid all but the most clunky of edits, even without any crossfading. With some short crossfades it was a piece of cake. You sometimes have to be a little more careful with bass edits, aligning the waveforms on either side of the edit point to avoid a level dip during the crossfade, but here the bass edits were covered by so many other parts in the arrangement that I didn't need to do that either.

Copying and pasting sections of a single rhythm-guitar part allowed a second part to be created, allowing the pair of tracks to be opposition-panned for a nice stereo effect. However, this necessitated careful editing to avoid timing discrepancies between the two tracks resulting in distracting stereo ricochets.The guitar and bass parts were easy enough to deal with using nothing more fancy than Cubase's normal Project window facilities. The edits for the guitar parts were very easy indeed, simply because the distorted timbres hid all but the most clunky of edits, even without any crossfading. With some short crossfades it was a piece of cake. You sometimes have to be a little more careful with bass edits, aligning the waveforms on either side of the edit point to avoid a level dip during the crossfade, but here the bass edits were covered by so many other parts in the arrangement that I didn't need to do that either.

On a couple of occasions where one of the guitar parts had come in very early on a chord, shifting the chord into time left a big gap in the audio, which wasn't really possible to fill convincingly simply by overlapping the audio regions on either side and crossfading — you ended up with what sounded like a little ghost note breaking through from one region or the other during the crossfade. In these few cases, however, Cubase's internal time-stretching function was more than up to the job of extending the end of the earlier region enough to avoid the problem. Another solution you can also try if you find yourself in this position is simply to leave a gap between the two regions, fading the first region out just before the next note begins, although the silence thus created between the notes can sometimes give the game away in practice.

Listening to the track from start to finish with the bass and guitar parts more in time, I could now hear that the song's momentum was beginning to come through a lot more as it progressed from the verses to the choruses. But when the central solo section kicked in, everything seemed to fall a bit flat because the rhythm guitar parts all dropped out behind the main lead line. So I extended the couple of bars of rhythm part that were already there to cover the whole section, chopping the chords around as necessary to fit with the solo and bass lines, and although this helped a bit, I still hankered for more rhythmic energy. I noticed that the rhythm was picking up quite nicely in the song's outro section, and as the guitar parts there were in the same key as the solo I tried ferrying those over as well. It worked like a dream and really helped keep things going until the third chorus.

Melodyne Manoeuvres

Having a tighter backing track was all well and good, but Richard had recorded his vocal overdubs alongside the original arrangement, and they didn't really fit very well any more. In addition, the tuning was a little suspect in a number of places. These are both things that I've dealt with on many previous occasions using normal sequencer editing facilities, but here I decided to turn instead to Celemony's Melodyne plug-in. I'd been using this for some very challenging vocal-editing work recently, and I knew that it would make much lighter work of the pitch-drift issues, in particular, than Cubase's envelope-controlled off-line pitch-shifting or an Auto-Tune-style automatic correction plug-in.

Here you can see one of the lead vocal phrases as it appeared in Melodyne after pitch and timing adjustments had been made. Notice that the pitch centres displayed needed to be off Melodyne's pitch grid in some cases to get subjectively natural intonation in practice. At the end of the last note, you can also see one of the expressive pitch fall-offs that Mike was careful to leave intact while making adjustments to note Pitch Drift settings.For those of you unfamiliar with the way the Melodyne plug-in works, it first needs to record and analyse the vocal track, after which it lays out the note waveform envelopes in a piano-roll display rather like Cubase's Key Editor, so that you can edit the pitch and timing of notes in much the same way as you can MIDI data. What I find in practice is that, while Melodyne is rarely fallible when it comes to detecting basic note pitches, it does usually encounter some difficulties splitting up the notes sensibly — several notes may be treated as one, for example, or one wavering note may be split up into lots of bits. Sorting out these misinterpretations before you start any proper correction work really helps make the final processing sound more natural-sounding, so after I've imported the audio into the plug-in, the first thing I typically do is select the plug-in's Note Separation tool and tweak the boundaries to match what I'm hearing.

Here you can see one of the lead vocal phrases as it appeared in Melodyne after pitch and timing adjustments had been made. Notice that the pitch centres displayed needed to be off Melodyne's pitch grid in some cases to get subjectively natural intonation in practice. At the end of the last note, you can also see one of the expressive pitch fall-offs that Mike was careful to leave intact while making adjustments to note Pitch Drift settings.For those of you unfamiliar with the way the Melodyne plug-in works, it first needs to record and analyse the vocal track, after which it lays out the note waveform envelopes in a piano-roll display rather like Cubase's Key Editor, so that you can edit the pitch and timing of notes in much the same way as you can MIDI data. What I find in practice is that, while Melodyne is rarely fallible when it comes to detecting basic note pitches, it does usually encounter some difficulties splitting up the notes sensibly — several notes may be treated as one, for example, or one wavering note may be split up into lots of bits. Sorting out these misinterpretations before you start any proper correction work really helps make the final processing sound more natural-sounding, so after I've imported the audio into the plug-in, the first thing I typically do is select the plug-in's Note Separation tool and tweak the boundaries to match what I'm hearing.

This is where I started work with Richard's vocal part. Because Melodyne had done a pretty good analysis job on this occasion, I was actually able to set the plug-in display's scrolling to follow Cubase's transport and do the corrections in real time as the song was playing, although this was only possible because I'd chosen the plug-in's Note Separation tool — the normal context-sensitive Select tool is a bit too fiddly to use at speed. On the next pass I selected the Edit Pitch tool and went through again zapping any suspicious pitching. This tool is, again, quicker than the Select tool, because it lets you double-click any note to quantise its pitch. You can also specify pitch offsets in cents (hundredths of a semitone) when using this tool, which is handy if you (like me) have developed an instinct for working in cents over the years.

One thing that's very important to mention about pitch-correction in Melodyne, is that, powerful as the software undoubtedly is, you still need to check everything by ear. When Melodyne analyses your audio, it internally averages the pitch fluctuations within any given note to decide on that note's 'pitch centre' for display and correction purposes, but our ears don't do this in quite the same way, which can lead to a disagreement between what Melodyne thinks the perceived pitch of a note should be, and what you actually hear it as. Clearly, if you don't do any pitch-processing, then this mismatch is irrelevant, but the moment you try to quantise a misinterpreted note to Melodyne's pitch grid you'll find that the note still sounds out of tune. So even though quantising the pitch of a note will work some of the time, you should be prepared to shift notes away from the Melodyne pitch grid if your ears smell a rat. Er... you know what I mean!

As I mentioned earlier, though, some of Richard's longer held notes were drifting out of tune, so straight pitch-shifting alone wasn't going to complete the job. This is where Melodyne really comes into its own for me, because its Pitch Drift tool allows you to sort out this kind of thing without ironing out all the smaller-scale pitch variations that make the voice sound human. In a lot of cases you can just turn the Pitch Drift setting to zero (again, easily done by double-clicking) with no ill-effects, but here the notes needed a little more finesse, because the pitch variations in a lot of the cases were adding to the expressiveness of the performance. Dialling the Pitch Drift percentages down into the 40-70 percent range gave the required control, and I then moved my attention to some timing issues.

Wherever you have a lead vocal that's up at the front of the mix, the singer's timing can have a great deal of impact on the overall groove of the track. For this reason, timing correction is often almost as important as pitch correction, yet many SOS readers seem to neglect the former even while overdoing the latter. You can do almost any typical time-correction task with simple audio editing if you know what you're doing, but it can take time to get clean edits. Melodyne makes the process a lot faster, so it didn't take me long to massage Richard's phrasing more into line with the tightened drum and guitar parts. It's worth reiterating, though, that you need to trust your ears more than your eyes when doing this, even more so in my experience with timing than tuning in Melodyne — I've never really had good results with Melodyne's grid quantising function when working with vocal parts, for example, however tidy it might make the waveform envelopes look in the plug-in window.

A final touch of Melodyne smoothed out some disagreements between the lead and backing vocal pitching, following which I bounced down the backing line and snipped it apart so that I could spread a pair of backing vocals either side of the lead. As a result of all that editing, the guitars, bass, and vocals were now much more unified, and the arrangement changes had increased the contrast and dynamics between the sections. However, listening back to the entire arrangement dispassionately after a night's sleep, there was no getting away from the fact that the drum parts simply sounded a bit lame.

Drums: Fake, Fake, Or Fake?

After auditioning some new drum loops against Richard's arrangement, to build a shortlist, Mike then sliced the loops with Propellerhead's Recycle and reimported the resultant REX files. This meant that the different loops could be used freely together without any time-stretching artifacts.I experimented with various mix processing techniques to beef things up, but no matter where I took the sonics, the basic part still shouted "Fake!" loud and clear. Now don't get me wrong: I've no problem with carefully faked drums, especially when their main purpose is just to keep the beat going and provide a general framework for a song. While nothing can compare with a great recording of an inspired live drummer, recording live drums is not really an option for many home musicians and there's now a large number of off-the-shelf software instruments and sample libraries that can deliver pretty reasonable middle-of-the-road results much more cheaply and conveniently.

After auditioning some new drum loops against Richard's arrangement, to build a shortlist, Mike then sliced the loops with Propellerhead's Recycle and reimported the resultant REX files. This meant that the different loops could be used freely together without any time-stretching artifacts.I experimented with various mix processing techniques to beef things up, but no matter where I took the sonics, the basic part still shouted "Fake!" loud and clear. Now don't get me wrong: I've no problem with carefully faked drums, especially when their main purpose is just to keep the beat going and provide a general framework for a song. While nothing can compare with a great recording of an inspired live drummer, recording live drums is not really an option for many home musicians and there's now a large number of off-the-shelf software instruments and sample libraries that can deliver pretty reasonable middle-of-the-road results much more cheaply and conveniently.

The key to getting the most successful results with such products, though, is that you need to simulate not only the sound of a live kit but also the performance of a live drummer, and that's where the Free Radicals had fallen down. They had used the well-respected Addictive Drums software instrument, so the sounds were alright in isolation, but they'd triggered the sounds in a very mechanical way that gave no impetus to the music. A real drummer naturally changes pattern to reflect changes in arrangement, and adds fills to build up to section boundaries, and this kind of musicianship was missing in the programmed parts.

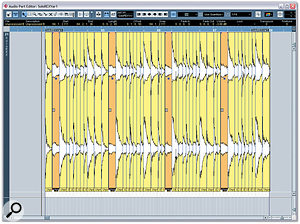

Because the loops were sliced, it was possible to rebalance some over-loud open hi-hat hits (the orange regions in the screenshot) in the song's middle section just by grabbing the region volume handles in Cubase's Part Editor.To be fair, it's phenomenally difficult to program musical-sounding drum parts, especially if you're not a drummer yourself, and a lot of software drum instruments (Addictive Drums included) acknowledge the importance of the performance element in the sound of live drums by including a library of expertly programmed MIDI grooves, which you can chain together to build a realistic-sounding part. In future I reckon the band will get a much better outcome from these than trying to generate their own patterns from scratch. Ironically, the Steinberg Groove Agent drums that they used on their original mix had a much better vibe to them, and I briefly considered reimporting those into the more recent mix. Until, that is, I listened again and reminded myself how nasty that phasing sounded...

Because the loops were sliced, it was possible to rebalance some over-loud open hi-hat hits (the orange regions in the screenshot) in the song's middle section just by grabbing the region volume handles in Cubase's Part Editor.To be fair, it's phenomenally difficult to program musical-sounding drum parts, especially if you're not a drummer yourself, and a lot of software drum instruments (Addictive Drums included) acknowledge the importance of the performance element in the sound of live drums by including a library of expertly programmed MIDI grooves, which you can chain together to build a realistic-sounding part. In future I reckon the band will get a much better outcome from these than trying to generate their own patterns from scratch. Ironically, the Steinberg Groove Agent drums that they used on their original mix had a much better vibe to them, and I briefly considered reimporting those into the more recent mix. Until, that is, I listened again and reminded myself how nasty that phasing sounded...

All of which meant that there was only one thing for it: replacing the drums. And although many musicians now seem to turn exclusively to software instruments for fake acoustic drum parts, I decided instead to put something together simply by editing a few live drum loops from one of my favourite little sample libraries: George Pendergast's Alt Rock Drums (which retails at £19.95 including VAT here in the UK). The big advantage with working from loops of a real drummer playing is that the performance and sound are both completely realistic. The apparent disadvantage is that the patterns are set in stone and you can't change the mix of the instruments at all — but in practice, you can actually do quite a lot.

Remix Reactions

The Free Radicals: "We sent our mix in to SOS to ask whether the right mix could give our home recordings a commercial sound. We knew our own mix was a long way off the mark, but needed to find out which part of the process was making us fall short. When Mike sent over his 'draft mix' the results were unbelievable! What hit us first was the power and excitement. The instruments were bright and defined, each seeming to command its own space. The sound is easier on the ear, fuller but lighter, and the song has a momentum from start to finish that draws you in.

The Free Radicals: "We sent our mix in to SOS to ask whether the right mix could give our home recordings a commercial sound. We knew our own mix was a long way off the mark, but needed to find out which part of the process was making us fall short. When Mike sent over his 'draft mix' the results were unbelievable! What hit us first was the power and excitement. The instruments were bright and defined, each seeming to command its own space. The sound is easier on the ear, fuller but lighter, and the song has a momentum from start to finish that draws you in.

"Although most of the arrangement has remained the same, what's really been an eye opener is the way Mike has chopped certain parts into different places, creating those 'magical sounds' that just give the music such attitude. We think the genre that our music fits into has been more defined by the style of the mix, and it's exactly where we wanted to be.

"When Alan built the original drums in Groove Agent, we thought they did a good enough job at the time, and Addictive Drums sound much better, but nothing could have prepared us for the sound that Mike has created. The drums are a lot higher in the mix than we would have dared put them, which of course means that they now lock everything together, and the fills give the whole drum track a realism that we were struggling to achieve.

"So our question has been well and truly answered: a very professional sound can be achieved from our front room — we just have to learn how to do it! A big thanks to Mike and SOS!"

myspace.com/thefreeradicalswexford

Drums Mk3

First, I needed to audition the loops in question against the arrangement, but this was very easy because the files were already in Acidised WAV format, so Cubase automatically adjusted their playback speeds to match the tempo grid. Inevitably that stretched a few of the loops far enough that the time-warping algorithm's panty-line began to show, but that wasn't a concern for basic auditioning purposes. Despite the title, I think Alt Rock Drums is actually more suited to funk than rock, so it took a little time to find suitable patterns for 'Fly Away', but there were enough appropriate ones hiding in there that I could assign different patterns to the verse, chorus, and solo sections, as well as having a few alternate loops available to furnish me with extra fills.

I then chopped up the shortlisted loops so that I could match them to the tempo of the track without having to use any time-stretching (thereby keeping the most natural sound). I chose to do this with Propellerhead's dedicated Recycle application, as I'm most familiar with how that works, but most of the main sequencers now have built-in facilities that can achieve much the same ends. If you happen to have a REX-format drum-loop library, this beat-slicing will already have been done for you, and many audio applications will import REX files directly into your project, matching the loop to your song's tempo automatically.

The only mix processing the new drum parts required was a gentle brush with Cubase 4's Envelope Shaper plug-in, just to get the kick and snare punching through a fraction more in the mix.One of the reasons I like the Alt Rock Drums loops is that they don't include many crash cymbal hits, which gives you the flexibility to add these over the top wherever it suits your particular song. In 'Fly Away', that meant that I could just leave the Addictive Drums cymbals going over the top of my new loop parts. I also left in the Addictive Drums kick part, low-pass filtered to underpin the rather busy Alt Rock Drums kick with a more straightforward rhythmic pulse.

The only mix processing the new drum parts required was a gentle brush with Cubase 4's Envelope Shaper plug-in, just to get the kick and snare punching through a fraction more in the mix.One of the reasons I like the Alt Rock Drums loops is that they don't include many crash cymbal hits, which gives you the flexibility to add these over the top wherever it suits your particular song. In 'Fly Away', that meant that I could just leave the Addictive Drums cymbals going over the top of my new loop parts. I also left in the Addictive Drums kick part, low-pass filtered to underpin the rather busy Alt Rock Drums kick with a more straightforward rhythmic pulse.

In the song's middle section, the open hi-hats in the Alt Rock Drums loop I'd chosen was a bit too forward for the mix. This isn't such a tricky thing to remedy in a sliced-up loop, because you can actually alter the relative levels of different loop slices by a surprisingly large amount before it begins to sound unnatural, particularly when there are no cymbals sustaining over multiple loop slices. Inevitably, there were also some moments where the specific drum pattern didn't quite work in context with the rest of the arrangement, but this wasn't exactly a disaster either, because it was quite easy to shuffle a few slices around to 'reprogram' the part, and as long as I left the slice start points in roughly the right places the groove remained pretty much intact.

The only real complication you might encounter when rearranging loop slices like this is that the disembodied sustain tails on neighbouring slices might not quite match. For example, a hi-hat slice directly following a snare drum slice may have a lot of snare sustain on it, and is therefore unlikely to work very well after a kick slice or in isolation. However, it's usually not too difficult to find another hi-hat slice in any given loop that has a more suitable sound for these situations, so this limitation is rarely very constricting, in my experience.

So there was no rocket science involved in building the Mk3 drum part from sampled loops, but the end result sounded much more musical than either of the previous drum tracks. Probably the fiddliest part of the job was fitting a fill from one pattern onto the end of another at one point, because the drummer's natural tempo fluctuations in each loop didn't quite match up with each other, but it was pretty obvious, looking at the slices in the Cubase Part Editor window, roughly where the timing was coming unstuck, and it didn't take me too long to slide a few slices around in time until the performance once again flowed more convincingly.

And Finally: The Mix!

Leaving my editing tools gently steaming in the corner and returning to the mix process, the rejigged arrangement turned out to be comparatively straightforward to mix. Most of the work was simply a question of achieving a consistent balance with EQ and different types of compression — I just kept experimenting with settings until I didn't feel the need to keep readjusting the channel faders. The drum sound was, of course, already pretty much in the can, although I used just a touch of Cubase 4's Envelope Shaper plug-in to pull up the kick and snare hits. Matching the rest of the track to the drums involved brightening most of the tracks to some extent, and this was primarily achieved with high-pass filtering and large-bandwidth peaking boosts in the 1-6kHz regions.

A final touch to the edited arrangement was the addition of a simple power-chord guitar part to reinforce the chorus rhythm-guitar sound, and this was double-tracked through a couple of different amp setups in Line 6's Gear Box.The bass needed a bit more low-end warmth (not the most common problem in Mix Rescues), which came partly in the shape of EQ and partly care of a sub-bass sinewave synth I layered surreptitiously underneath — something I dealt with in more detail back in SOS May 2008's column. The chorus rhythm guitars also felt as if they needed a little bit of reinforcement, in a way that EQ couldn't deliver, so I quickly double-tracked a few power-chords (the sum total of my guitar technique!) through a couple of models in Line 6's Gear Box and slipped those in at low level. In the chorus, the lead vocal was a bit soft-sounding next to the guitars, so I used a distortion send effect on that, just to toughen it up so it could still cut through.

A final touch to the edited arrangement was the addition of a simple power-chord guitar part to reinforce the chorus rhythm-guitar sound, and this was double-tracked through a couple of different amp setups in Line 6's Gear Box.The bass needed a bit more low-end warmth (not the most common problem in Mix Rescues), which came partly in the shape of EQ and partly care of a sub-bass sinewave synth I layered surreptitiously underneath — something I dealt with in more detail back in SOS May 2008's column. The chorus rhythm guitars also felt as if they needed a little bit of reinforcement, in a way that EQ couldn't deliver, so I quickly double-tracked a few power-chords (the sum total of my guitar technique!) through a couple of models in Line 6's Gear Box and slipped those in at low level. In the chorus, the lead vocal was a bit soft-sounding next to the guitars, so I used a distortion send effect on that, just to toughen it up so it could still cut through.

I did set up quite a few send effects, though, mostly various processed delays to give the different guitar and vocal parts different characters, while still blending them together. One of the main problems in Richard's mix was that he'd used too much long reverb, and I only felt the need for a dab of a typical hall patch here and there, mostly for the cymbals and some of the more sustained guitar lines. (Richard had also been using Cubase SX's built-in Reverb plug-in, but after a few friendly beatings he seems to have realised the error of his ways...) Automation? Hardly any — that's one of the areas where getting the arrangement sorted out can really save you lots of effort.

The bottom line is that I did all the heavy lifting with this track before I even started the actual mixdown, and when an arrangement works it shouldn't be difficult to get it to balance. So if you're struggling getting your own mixes to a point where you're happy with them, maybe it's a clue that you need to go back to the editing stage to mould the tracks into a form where they'll mix themselves.