Classic rock: even well-recorded drums can require plenty of work to make them fit the track.

Although it’s perhaps not my own first choice in terms of everyday listening pleasure, I always quite enjoy mixing classic-rock tracks. It’s a genre that has refreshingly well-defined goals to aim for: getting the guitars sounding big but also spacious, deciding if that snare is too much, and how to sit a powerful vocal in the mix are all fairly obvious but often challenging processes, and they’re crucial to crafting a powerful, exciting mix. There’s a huge amount of satisfaction to be had from getting all of this rocking like it should!

Thus, I found myself fairly excited at the prospect of mixing a straight-down-the-line-rock number called ‘Bloody Mary’ by Australian outfit Thunderbird. After talking to the guitarist, Rod, I was also quite intrigued by how the band had pieced the track together. Classic rock it may have been, but it had certainly been put together in a thoroughly modern manner: the team behind it are all Australian, but the guitarist recently moved to the UK, the song writer resides in New York, the drums were tracked in Canada and the bass was laid down in Costa Rica!

This was the first time I’d worked on a style of music that is described as ‘Australian pub rock’. Far from being a derogatory term, this describes a brand of rock music that originated in small Australian inner-city pub-style venues in the 1970s and ‘80s, with its most famous exponents being a certain school-uniform-wearing band with a penchant for Gibson SG guitars.

After a few discussions about how the mix process would progress, I received a Pro Tools session with the song ready to mix. Also included were some broad but constructive notes about the band’s general mix preferences, and a couple of reference tracks that they thought might be useful. They were: I find it extremely helpful when a band sets out their stall like this, and although I didn’t have a rough mix to listen to I still felt like I had a strong sense of what the band were looking for. Even just a few pointers can be useful when you’re engaging a mix engineer to work on your track. Knowing that you don’t want timing correction on the drums, or that you like a ‘tucked in’ lead vocal or a full, punchy kick and snare sound is really helpful when trying to establish an early sense of direction.

Cracking On

Whenever I’ve not been given a rough mix, it’s always something of a fingers-crossed moment when I first open the session. The drum sound is so important to the rock genre and, despite the ease with which we can incorporate samples these days, compromised drums can quite quickly create a ‘ceiling’ in terms of overall sonic quality. From a more selfish point of view, I also find that it affects how enjoyable a mix is to work on! So you always find yourself hoping that the drums have been played nicely and well recorded...

It was with some relief, then, that when I first hit the play button, I was greeted with a well-recorded kit, replete with a typical compliment of close, overhead and room mics that would enable me to fashion the sound as I wanted. The kick drum in particular sounded great, and my only real area of concern was the amount of bleed I’d have to contend with on the three close tom mics.

Even when drums have been captured well, though, there’s rather more to making them work in a rock track than getting the levels right. Even with a good drummer, the kick and snare will need ‘hyping up’ somewhat, and the cymbals usually need to be ‘set back’ slightly more than they would be naturally if you were standing listening to them being played in the same room. So, after a little more general balancing and mix organising, I decided to spend a good chunk of time getting the drums sounding right.

Towards A Drum Sound

I’m someone who has probably spent too many hours of his life fiddling with drum sounds, so I know how the process tends to pan out for me. It’s very much about getting the drum mix set up in a way that’s designed for that final non-technical part of the mix where things just need nudging and massaging into place. I’ll come back shortly to how I manage this, but at this stage the job was all about the broad brush strokes I’d use to define those all-important kick and snare sounds.

Each of the supplied reference tracks had different flavours of the classic ‘exploding’ rock snare, and I was looking forward to creating my own version of this. Aside from some clever Phil Collins-style room or talkback-mic gating techniques (that, for various reasons weren’t available to me here), the primary tool for crafting this sound is reverberation, so I set about preparing my snare to be suitably detonated using a reverb plug-in. For an over-the-top snare sound like this, it’s important that the snare can be successfully isolated from other elements of the kit — if hi-hat and bleed from the wider kit is fed into bucket loads of reverb it’s just going to create an exploding mush.

I’ve acquired some great new tools for drum processing recently, and this seemed the ideal project on which to use them to do some of the heavy lifting. The first is Drum Leveler by Sound Radix, which is a really useful plug-in. It lets you even out the hits in a drum recording and create a more solid and consistent feel to the snare or other elements of the kit. It’s a little like compression in that respect, but as the whole of each hit is boosted or attenuated and its envelope not changed, it can sound more natural. The resulting consistency also makes it much easier to isolate sounds using conventional threshold-dependent processors such as gates and expanders. Whilst Drum Leveler has a perfectly serviceable gate built in, it seems that not all gates are created equal. After a little experimentation, I found that using Drum Leveler to do the levelling and then using (my second new toy) Softube’s Valley People Dyna-mite plug-in for the gating worked a treat — it left me with a nice, clean, isolated close snare mic channel.  Sound Radix’s Drum Leveler plug-in was used to varying degrees on the drum close mics to bring consistency to the main drum hits.

Sound Radix’s Drum Leveler plug-in was used to varying degrees on the drum close mics to bring consistency to the main drum hits.

I applied the same technique to the kick drum close mic, but slightly less aggressively; I always like to leave a little of the bleed in there so that the kick doesn’t sound too ‘clipped’. It was just a matter of setting up the gate and then dialling back the attenuation until I was left with the right amount of isolation. The tom mics were more problematic — although I was able to repeat the same trick yet again on two of the toms, this didn’t get me all the way there, I still had to go in and manually isolate a number of hits. (I know producers of metal, and other heavy genres, who do this kind of meticulous editing as a matter of course with drums, and the amount of time and care devoted to getting the right sound really can be truly astonishing!)

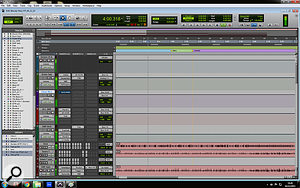

With the majority of the drum-prep work complete, I began to fine-tune my overall mix setup so that I could ‘massage’ all these disparate drum elements into a more coherent whole. As the reverb for the snare is such a vital element, I like it to have its own dedicated aux channel. A lot of DAWs will position such channels to the right of your mixer, which makes a certain amount of sense for global send effects, but for source-specific applications like this I prefer to position the aux track adjacent to the source. I’ll also usually set up a number of groups/sub-mixes, to give me more control. Here, this included a sub-mix fader for all the elements of the snare sound (top and bottom mics, reverb, samples and so on) and a further sub-mix for all the close mic elements of the kit, including the snare. These will all be fed into a master drum-bus and, finally, I’ll have a VCA channel set up in Pro Tools, with which to control the overall level of the kit.

Why do you need a VCA channel? Well in Pro Tools at least, if you just use the drum bus for adjusting the level of the whole kit, it doesn’t change the level of any individual tracks’ sends relative to the kit volume, so boosting or reducing the level of the kit will also alter your hard-won balance. Some of the sub-mix channels are also used for applying processing en masse to a number of tracks, but the main advantage of this rather complex setup is that when it gets to that crucial last five percent of a mix, you’re able to fine-tune things quickly and easily. Being able to carefully adjust the close mics against the overheads, and being able to fine-tune levels without affecting compression or effect sends, is crucial if you’re to get the right balance and feel. It also means that you can easily make any specific revisions requested by the band, without throwing other things out of kilter. Softube’s Valley People Dyna-mite was inserted after Drum Leveler to gate the close snare signal.

Softube’s Valley People Dyna-mite was inserted after Drum Leveler to gate the close snare signal.

Building The Picture

I’d return to my exploding snare later, but first it was time to lick the other elements of the mix into shape. For the bass guitar, I’d been supplied with a DI track that had gone through some tasteful amp emulation, along with another version of the same thing but with a bit of drive and distortion. After checking their phase relationship, and balancing these two tracks so that they were roughly even in level, I was pleased to find that they seemed to require very little by way of processing. I applied a little EQ boost around the 1-2 kHz region, to give the sound a bit more presence, and decided I would wait to see how the (quite generous) bottom end fared when I got a bit further down the line.

Despite the band’s desire to have the vocals ‘tucked in’, the vocal sound is important in any track. It’s the element that most listeners identify most strongly with, and arguably listen to most critically. With that thought in mind, I like to get the vocals sitting against the drums and bass before I do too much work to fit the guitars in. Given the style of vocal, most of the work in shaping the sound is done during the performance, but I still felt that I could lend the part a greater sense of energy and presence, without making it sound obvious that I’d messed around with it!

On listening, it struck me that the vocal had probably already been treated to a little compression during recording. Also, it was also a pretty full-on performance throughout, so I felt little need to perform any major levelling work. But compression is not just about evening the levels, and I found that applying a decent dose of compression via an 1176 emulation brought a familiar and reassuring tone. I also liked what an instance of the Soundtoys’ Radiator (which, essentially, is an emulated valve distortion processor) added to proceedings — the vocal part now felt like it had some useful extra urgency and attitude. There was a downside to all this, in that it resulted in a little extra harshness, but that was easily countered with a little EQ dip around 2kHz and some careful de-essing.

With the part now sounding more like I’d envisaged, I could think about defining a sense of space around the lead vocal. I really liked the effect that a little slap echo provided, and sent this in turn to an instance of a simple plate reverb plug-in. This vocal processing was fairly quick and painless — it felt somehow right, given the style, that it should be treated relatively simply. After a little automation to raise the level of the vocal part and it’s effects during the chorus sections, it seemed good to go. Neil set up complex drum-mix routing to allow easy fine-tuning of and control over the drum tracks and their effects sends.

Neil set up complex drum-mix routing to allow easy fine-tuning of and control over the drum tracks and their effects sends. Along with a little EQ dip at 2kHz, some de-essing with the Fabfilter Pro-DS helped tame some harshness on the vocal.

Along with a little EQ dip at 2kHz, some de-essing with the Fabfilter Pro-DS helped tame some harshness on the vocal. Some slap delay via Soundtoys’ Primal Tap plug-in was fed into a plate reverb to provide a sense of space around the vocal.

Some slap delay via Soundtoys’ Primal Tap plug-in was fed into a plate reverb to provide a sense of space around the vocal.

Adventures In Emulation

With the vocals sitting nicely against the drums and bass, it was time to get the guitars properly involved and, hopefully, make it sound like a proper rock track! Rod, the architect of the Pro Tools mix session, as well as the guitarist, had recorded his parts at home using his Egnator Tweaker 15 head as a preamp of sorts. He’d then used Overloud’s TH3 amp and cabinet emulation plug-in to try to give it the roundness and depth of sound you’d get from a real cabinet. Rod was a little unsure of what to give me in terms of files, and I suggested he send me two different versions of the guitar: one rendered with the processing he’d used, and another just the raw DI signal, but with the TH3 plug-in left in the chain. I had access to the software he’d used, so I’d be able to tweak what he’d done and see what sort of results I could achieve that way.

I also have various guitar cabinets and mics, and the means to be able to re-amp DI signals properly, so I spent a little time in my studio running the direct signal out through a real-life Marshall stack-type set-up, just to see if it could add anything of interest in comparison with the emulated processing... Unfortunately, the result was slightly disappointing — there certainly wasn’t any clear improvement. After speaking to Rod, and establishing how he’d recorded the guitar, I suspect that the fact that the signal had already passed through an amplification stage was rendering my experiment somewhat futile. If you’ve already tracked via a preamp like this, to re-amp you need to be able to feed the power-amp stage of the amp directly, which wasn’t an option at the time. Having recorded a couple of abortive passes, I decided my time and energy would be better spent working with the tracks I had already — that wasn’t really a problem, as they sounded more than passable.

Back To That Snare

With all the elements of the track now in place, it was time for me to complete work on that snare sound, and from there head towards the final stages of the mix. I’d auditioned several reverbs to get the effect that sounded right for my main snare sound. I ending up settling on Waves’ TrueVerb plug-in, simply because — how shall I put this politely? — some of the other reverbs sounded a bit too good. Given the quality of reverb plug-ins that are available today, this might sound an odd sort of statement, but I’m not always looking for a sense of realism from spatial effects. Rather, I’m trying to create or evoke a particular vibe; in this case, a slightly cheap ‘80s-sounding reverb. On the aux channel on which I’d placed TrueVerb, I added a good helping of compression and limiting to get the effect to sound more ‘explosive’, and I also EQ’d out some of the top end and very low bass frequencies. As well as applying bucket loads of this reverb effect, I created a duplicate of the snare track which I processed to sound extremely crunchy and aggressive, courtesy of a combination of SoundToys’ Decapitator distortion plug-in and some over-the-top compression. This, effectively a parallel distortion effect, was then blended in slightly under the main snare sound, to help lend the snare a little extra attitude. Overloud’s TH3 plug-in had been used by the band to replicate the large cabinet sound traditionally associated with this style of rock music.

Overloud’s TH3 plug-in had been used by the band to replicate the large cabinet sound traditionally associated with this style of rock music. To help create the trademark rock snare sound, plenty of reverb was used, along with some compression and EQ on the reverb’s aux channel.

To help create the trademark rock snare sound, plenty of reverb was used, along with some compression and EQ on the reverb’s aux channel.

Shaping The Final Mix

I’ve focused quite a bit on the lengths I went to so that I had the ability to fine-tune the drum sounds, but it’s worth a note of caution. While a certain amount of such work can pay serious dividends, you could go on doing this forever — we’ve all been there in the early hours of the morning, tweaking this element and that, only to realise that it’s all gone to pot! There comes a time when you have to slap yourself on the wrist, take a step back and force yourself to focus on the bigger picture.

A simple tip which can help in this respect is to make sure you take regular breaks during the mixing process, giving you a chance to ‘reboot’ your ears. This will help you keep a sense of perspective on the track, as well as avoiding listening fatigue, which is something that can lead to poor level and EQ judgements all too easily. While I’d encourage you to try and develop your own techniques and routines, it’s perhaps worth saying that I like to have an extended break, ideally leaving things overnight, before returning to the mix. The idea is that all the unnecessary or counter-productive fiddling stops: I return to work with what I have and get it balanced. Having some sort of lower-fidelity listening system available can be helpful in shifting the focus, too, and I’ll often start this new phase by listening through the little stereo I have at the back of the room.

I remained very conscious of the fact that the band had requested a ‘tucked-in’ vocal, so I made a point of placing it a little lower than I typically would have done. The trick when doing this is to ensure that you can clearly make out all the lyrics — and as long as I stuck to that principle, I was happy that the levels were right for the track.

I’d noticed also, whilst listening through my ‘lo-fi hi-fi’, and also in my car, that the bottom end of the bass guitar sounded a little overblown on certain notes. I was reluctant to start carving the bass up with EQ at this stage, and found that using just one band below about 200Hz on a multi-band compressor helped just firm up the really low-end elements of the bass without seeming to affect the overall perceived level of the part.

I spent the majority of the remaining mix time making small changes to the relative levels of the drums, vocal, bass and guitars, whilst trying to manage the overall tone of the track in relation to the reference tracks that I was using.

Final Thoughts

One of the things about a great rock mix that always impresses me is how the guitars seem to sound so loud without smothering the rest of the band. I’m not 100 percent sure that I quite managed this for ‘Bloody Mary’ — while I think that many guitar-amp emulation options are really good, especially for re-amping as opposed to playing, I’m confident that I can still achieve better results when I can record the real thing with the player in the room. Still, it helped get it fairly close, as I hope you can hear from the audio examples on the SOS web site (http://sosm.ag/feb16media).

As I wrapped things up, another thought occurred to me that I’d like to share with you. Given that this music is fairly simply arranged, with just four main elements, it took a considerable amount of time to get things sounding how I wanted! The majority of the time spent was on the drums, and trying to establish how best to make use of the supplied guitar options. There were certainly a few points at which I asked myself if I was doing too much processing for both these instruments. Even if you’re happy with where you end up, as I was here, I think it’s important to ask yourself if you’re spending too long chasing a particular sound in your head. Who knows, maybe you could get just as good results a lot more quickly? Although it didn’t happen for this mix, I’ve sometimes found self-questioning like this leads me to start from scratch, and eventually to far better results. Having a good system for checking references (see box) was really important for this mix and it helped me not only shape the sound and balance of the mix, but to give me a confidence boost when I was faced with those inevitable mid-mix doubts.

Using Reference Tracks

I’ve recently made quite a few changes to my mixing setup, so I’ve made a real point of carefully checking my work against reference tracks that I know well or think sound good out in the real world. I also had, in this case, to compare my mix against the tracks that I’d been supplied with by the band.

In the past, I’ve sometimes just plugged my phone straight into my monitor controller and listened to a track via a streaming service. But while that can tell you something useful, I try hard not to do this because, sonically speaking, such sources can be misleading. I think it’s important to audition your work against a high-quality MP3 at the very least — and preferably an uncompressed or losslessly compressed source.

Fab Filter’s Pro-MB multi-band compressor was used to achieve a little gain reduction on the bass guitar only for frequencies below around 200Hz.To help make this important referencing process a little easier, I’ve been using Sample Magic’s fantastic little Magic AB plug-in. You place this at the very end of your mix-bus processing chain and load up to nine other tracks into it. Importantly, it allows you to level-match these tracks so that you can make comparisons without the differences in loudness skewing your perception of what’s good and bad. As well as helping you compare with other people’s mixes, I’ve found that it makes it really easy to check your progress against an earlier version of the mix, and that’s really useful if you’ve been working on a specific aspect of the track, or are making changes having listened at home or in the car, or are working on revisions requested by the band.

Fab Filter’s Pro-MB multi-band compressor was used to achieve a little gain reduction on the bass guitar only for frequencies below around 200Hz.To help make this important referencing process a little easier, I’ve been using Sample Magic’s fantastic little Magic AB plug-in. You place this at the very end of your mix-bus processing chain and load up to nine other tracks into it. Importantly, it allows you to level-match these tracks so that you can make comparisons without the differences in loudness skewing your perception of what’s good and bad. As well as helping you compare with other people’s mixes, I’ve found that it makes it really easy to check your progress against an earlier version of the mix, and that’s really useful if you’ve been working on a specific aspect of the track, or are making changes having listened at home or in the car, or are working on revisions requested by the band.

Mixed This Month

Thunderbird are an Australian hard rock band featuring Marc LaFrance on vocals, Rod ‘Doc’ Coogan on guitars, Rob Becker and Tim Rath on bass, and Kelly Stodola on drums. You can find out more about them on their Facebook page.