In part 2 of this series, Oli Bell offers advice on choosing a sampler for modern styles, finding and using samples from the Internet, and deciding which sample CDs to buy. This is the second article in a three‑part series.

Last month we looked at some of the theory involved in sampling as well as some good places to search for audio inspiration. But before you run off and raid granny's vinyl collection you'll need a sampler to work with. With so many models now available, costing anywhere from a couple of hundred pounds up to a couple of thousand, it can be difficult to decide which sampler is right for you. So here are a few tips on what to look out for when buying a sampler for dance music production.

Buying Basics

Though hardware samplers, such as Akai's top‑of‑the‑range S6000, have been developed into extremely powerful tools within the last few years, software samplers, such as the Nemesys Gigasampler, might better integrate with the MIDI + Audio sequencer systems used in many modern productions.

Though hardware samplers, such as Akai's top‑of‑the‑range S6000, have been developed into extremely powerful tools within the last few years, software samplers, such as the Nemesys Gigasampler, might better integrate with the MIDI + Audio sequencer systems used in many modern productions.

The first, and arguably most important, factors to look for in a prospective sampler are the sampling quality and memory available, both of which are fundamental to the operation of the sampler. Sampling is very heavily relied upon in certain types of modern music production, and it is important therefore that the sampling rates and bit depths which your sampler can offer will allow you to achieve the appropriate sound quality for the style of music you're working with. While the majority of serious modern samplers now offer sample rates up to at least 44.1kHz at 16 bits, which is ample for pop and dance production, those on a budget will have to consider older, less high‑fidelity machines — if you're in this position then check out the 'Oldies But Goodies' box for some of the best machines of the past.

<!‑‑image‑>As for onboard sample memory, my advice is to get absolutely as much as you can afford, because it's easy to underestimate how much you need. This is particularly relevant when buying discontinued machines — it might be extremely difficult to find a memory upgrade for a discontinued sampler, so be sure to check that the RAM in a secondhand machine is adequate. A lot of the samples now used in modern music production, such as loops and vocal/instrumental phrases, tend eat up onboard RAM very quickly, particularly if you sample in stereo. The last thing you want is to run out of memory before you can drop that final killer sound into the mix.

LFO Sightings

Many samplers now offer some synthesis features, allowing you to mangle the pitch, tonal‑quality and volume in real time, often under the control of onboard envelopes/LFOs or in response to received MIDI controllers. The importance of such features nowadays is not to be underestimated, and filtering in particular is fundamental to many forms of dance music. If you have MIDI‑controllable resonant filters, many extremely characteristic modern sounds are immediately open to you — for example, if you have a sampled sawtooth waveform, you only need to run it through a high‑resonance low‑pass filter with the cutoff point under MIDI control, and you have access to instant TB303‑style burblings. Anything and everything can be subjected to filtering and envelope manipulation when you're searching for inspiration — breakbeats, loops, vocals, sampled pads and rhythm guitars commonly — and it can feel very limiting in the current musical climate to be without this valuable creative tool.

Effects are also extremely valuable for most styles of modern music, but it's not nearly as important to have these built into the sampler itself, particularly if the sampler forms part of a larger studio setup. There are now many different stand‑alone effects processors on the market which will do the job very nicely, though you may want to buy a sampler with multiple assignable outputs if you're wanting to process individual sampled sounds separately.

Let's Interface

<!‑‑image‑>If your budget can stretch to it, another important feature to look out for in a sampler is the inclusion of a SCSI port on the sampler's rear panel. SCSI (small computer systems interface) is a fast method of data transfer which has a number of uses for the phrase samplist. For a start, it can give you access to external high‑capacity storage devices, on which you can store your samples. There are a number of options here, including fixed and removable hard drives and a number of lower‑cost removable‑media drives, such as Iomega's Zip and Jaz. The luxury of large amounts of storage space allows you to amass a library of hundreds of samples which you can dip into very quickly — certainly more quickly than you can when loading samples over MIDI or from floppy disk. Speaking from frustrated experience, there's no point in having a fantastic loop if you can't find it amongst a mountain of floppies, or if your inspiration vanishes while you wait for it to load up. For many samplists, having a SCSI connection is also very important because it allows the connection of a CD‑ROM drive, opening up the possibility to access the wealth of ready‑made samples on commercial CD‑ROMs.

Another advantage of having a SCSI port is that it can be used to connect the sampler directly to a computer. (The computer in question will also need a SCSI connection, obviously.) This allows sample data to be moved between sampler and computer, where it can be edited using any number of audio editors with intuitive graphical interfaces — much nicer than staring at a line of numbers on a sampler display! Once edited and manipulated, the samples can then be sent straight back to the sampler for playback.

Hard Choices & Soft Options

<!‑‑image‑>Even once you've decided how you stand regarding the important issues above, there are still several different types of sampler you can go for. If you already have a studio setup with sequencer, master keyboard, mixer and effects, then there's much to be said for the extensive feature sets and flexibility offered by many rackmount samplers. However, if you're working with only limited equipment, it might be better to go for a sampling workstation; something which perhaps combines sampling and mixing with sequencing and MIDI control. Some of these systems are built into a keyboard controller, such as Korg's Triton workstation, while others, like Akai's MPC2000XL, occupy desktop boxes incorporating trigger pads. The integration of such systems can be very convenient and can make for speedy use, and they are also often designed to be as useful on stage as they are in the studio. However, the sampling features on offer in these one‑stop systems can sometimes seem rather limiting if you're looking to get really creative with manipulating your samples.

If you already use a computer in the studio, then software sampling will also be available to you. This has the advantage of packing a pretty impressive price‑to‑features ratio, because it relies upon the existing hardware of your computer. What's more, storage and organisation of samples is a breeze and sample length is only restricted by the amount of RAM in your computer. The integration that some of the more recent software samplers offer with leading computer sequencing packages is also another major plus point, cutting out the need for any separate interfacing software.

While the flexibility and visual interface of software samplers can be incredibly creative, they are currently best run on fast computers with plenty of RAM and hard disk space available, especially if they are having to share the CPU's processing with other piece of studio software running simultaneously. Even quite powerful computers can sometimes struggle to cope with songs that use too many audio tracks, virtual instruments and plug‑ins at once, and a computer struggling to cope is likely to be prone to frustrating audio or MIDI glitches and crashes. But if you've got the computer hardware to handle it, soft sampling may well be the future.

Whichever model of sampler you go for, remember, at the end of the day, it's the music you make that is the most important thing, not what gear you made it on. There are plenty of top producers who make outstanding tunes with very basic setups, so don't be fooled into thinking that bigger is always better. The average punter doesn't care about which model, filter or sample rate you used to make them move, only the fact that you made music which was good enough to make them move.

Using Samples From The Internet

In the first part of this series, I showed you some of the ways in which you could lay your hands on inspirational sounds for sampling by trawling through the LPs and cassettes of yesteryear. However, now that the Internet is with us, the variety of sounds available to the sample hunter has multiplied considerably. There's a wealth of digital audio available for download from the web, and lots of it can be put to good use in your music — see the 'Sample Sites' box for some of my favourite download sites. However, you'll need to be aware of some of the different formats this audio can be presented in, and how you can convert them (if necessary) into something your sampler knows how to use. Probably the most plentiful and useful samples available on the web are WAV and AIFF files, which can provide excellent sound quality and are compatible with many modern samplers. The newer Akai, Emu and Yamaha machines are capable of reading WAV files directly from disks in MS‑DOS format, for example.

If you wish to use these files, but your sampler doesn't read them directly, there are a number of solutions available which can convert them for you. One of my favourites is the AkaiDisk utility (available for download from www.mda‑vst.com), sometimes known as Adisk, which lets a PC read, write and format Akai S‑Series sampler floppy disks. It works with all S‑Series samplers from the S900 to the S3200XL, and converts samples to and from 16‑bit mono WAV files. Even if you don't own one of the Akai samplers, almost all modern samplers will read at least one of the Akai formats, which makes this a fantastically useful program. Obviously, converting WAV files to Akai format will only convert the raw sample data, and you'll need to edit this sound and set its program parameters and keyboard mapping before you're be able to use it.

If you work with a software sample‑editing program, this may also provide the facility to transfer sounds directly to your sampler, either over SCSI or MIDI connections. SCSI dumps are much faster and more convenient than MIDI sample dumps, but they do require both your sampler and your computer to have a SCSI interface fitted. MIDI sample dumps can be used with samplers which are not SCSI‑compatible; this usually involves setting up two‑way communication (where your sampler's MIDI Out is connected to your computer's MIDI In, and your computer's MIDI Out is connected to your sampler's MIDI In) and waiting patiently for several minutes longer than you would prefer while the sample is transferred.

<!‑‑image‑>There are a number of programs available which offer this kind of editing on a budget. Akai's MESA, for example, offers software editing for Akai samplers and is available as freeware for both Mac and PC from their web site (www.akaipro.com). Yamaha's Tiny Wave Editor offers similar support for their popular A‑series samplers, and is also available from their web site (www.yamahasynth.com). Mac musicians will be very interested in Stefano Daino's excellent Dsound Pro (available as shareware from www.d‑soundpro.com), which supports SCSI dumps to a wide range of samplers and is also capable of reading some Roland disk formats.

Feeling Compressed

The main problem with downloading samples from the Net is the length of time it takes to do so. As affordable, fast, broadband connection for the home still seems a fair way off in the UK, downloading a large sample file takes time (and patience). To get around this problem and to speed up download times, many samples on the net are data‑compressed in some way. One of the most popular types of compressed audio on the net is the now infamous MP3 format. MP3s are substantially smaller than WAV files, although there is a drop in the audio quality. Most of the popular MP3 players, such as Winamp (available from www.winamp.com) allow you to convert and save MP3 files as WAVs, as do sample editors like Syntrillium's Cool Edit Pro. The latest version of Cubase VST also supports the import of MP3s into audio tracks which, again, can be later saved as WAVs.

Even when you download only WAV files, some of these might still be using data‑compression. Uncompressed WAVs, often called PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) WAVs, are probably most common, but there are also a number of compressed WAV formats as well — DPCM (Differential Pulse Code Modulation) and ADPCM (Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation), for example. Even if you're happy with the sound quality of a compressed WAV, you'll still need to convert it to a normal PCM WAV before it can be used, even in WAV‑compatible samplers.

Sample CDS

The sample CD market has vastly increased in size over the last few years, and it seems there is now a sample CD available for almost any genre of music you can name. From classical orchestras and exotic instruments, to techno monster‑synths and hip‑hop beats, there is probably a sample CD to suit your style of composition. This staggering diversity opens up to the home studio a vast library of samples and styles that was previously unavailable or just too expensive.

Both audio CDs and CD‑ROMs are available — audio sample CDs have the advantage of being cheaper and usable in any sampler, new or old, but with the disadvantage that you have to construct your own programs to use them. CD‑ROMs, however, have the advantage of being able to store samples ready‑trimmed along with relevant program data, meaning that you can spend a lot less time programming and a lot more time playing.

There are a large number of producers who refuse to use sample CDs on principle. Some prefer to create every sound from scratch, while some purists will only ever sample from original vinyl — not even from compilations or re‑issues! However, for those of us without a studio full of gear, a huge budget, or the London Philharmonic's home number, sample CDs offer an effective and sometimes inspirational production tool. The only difficulty can sometimes be deciding which of the titles compatible with your sampler to choose!

Be sure to check out sample CDs that are aimed at different musical styles. It's easy to become blinkered and only go for disks that relate directly to your own genre of production, but exploring CDs aimed at other styles can really bring fresh ideas to a track. For example using 'real' choir or string samples instead of synthetic ones can add atmosphere, whilst live ethnic percussion can energise a tired four‑to‑the‑floor house loop. In particular, a mixture of organic and synthetic sounds works well, a classic example being the pairing of acoustic bass samples with heavily synthetic skittering rhythms in drum & bass.

As with any sound source, it is vital that you try to find an opportunity to take a good, long listen to a sample CD before you buy it. This shouldn't be too difficult these days, as many shops provide demo stations now and sample CD manufacturers will often provide demo sounds on their web sites. For example, Time & Space, the UK's biggest distributor of sample CDs, have jukeboxes installed in some of the bigger music stores around the country. At £50‑100 a shot, sample CDs aren't cheap, so you should make sure that there is a high percentage of the sounds that you really are going to 'use to death', before paying out your hard‑earned cash. Furthermore, remember to check that all the sounds included are totally copyright free — a few sample‑CD producers require a credit if you use their sounds on a track.

When you do get a chance to listen to one of your prospective purchases, there are a few things to bear in mind. Firstly, remember that samples normally have to sit alongside your own programming, so try not to be swayed by showcase sounds that are already amazing on their own — you'll have trouble fitting them into a busy mix. Also be wary of samples that are doused in effects that you can't remove, sounds that use wild panning techniques which can clog up a track's stereo image or which contain dominant frequencies that may smother whole frequency ranges of your mix.

That's all for now, but look out for part three of this series next month, where I'll be looking at how modern music styles are actually created with your sampler and its now well‑stocked sound library.

Oldies But Goodies

Although there is a multitude of brand new samplers on the market at the moment, it's also worth casting your eye (and wallet) over some of the older models available secondhand. You are unlikely to get all (or indeed any) of the up‑to‑date features that modern samplers can offer, or the flexibility of massive amounts of available memory, but what you do get is character — bags of it! The older machines sample less cleanly and accurately, but any roughness or colour that is added to the sample because of this becomes almost a trademark of each machine and an attractive plus for many users. Owners of such older samplers tend to be fiercely loyal to their machines, (a fact borne out by most manufacturers making new samplers backwards compatible and therefore able to read disks from earlier models). It's not the age of your sampler that counts, it's what you do with it.

Getting Started With A Sample CD Library

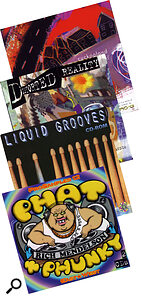

While sample CD choice is often a very subjective matter, there are a few releases that stand out whichever modern style you're involved in. Below are a few favourite general‑purpose libraries which not only provide a great starting point for production, but which can also act as a quality benchmark against which to judge any other prospective purchases.

<!‑‑image‑>• Cuckooland

Two volumes of this innovative Zero G sample collection are available. In the September 1996 review of volume one, the SOS reviewer commented that "if this doesn't breathe new life into your compositions, then I'm a large Swiss cheese called Brenda".

- Distorted Reality

This Spectrasonics release is also available in two volumes, and the second of these prompted our reviewer in SOS February 1999 to comment that "the only reason I'm giving this set five points out of five is because the art department refuse to create new graphics for five and a half points!"

- Liquid Grooves

Another Spectrasonics release, this collection of rhythm grooves was found to be "a masterpiece of layering, effecting and processing" by the reviewer in SOS June 1997.

- Phat And Phunky

Rich Mendelson's great‑value construction kits were reviewed in October 1999. The SOS reviewer said that "the subtle use of guitar and keyboard sounds linked with the sheer number of usable drum and FX samples should give this release real staying power".

Here are a few examples that I think are worth looking out for:

- Akai S900/S950

Rackmount units with 12‑bit sampling at 48kHz, 750K RAM expandable to 2.25Mb, basic synthesis facilities (low‑pass filter and two LFOs). A classic, which sounds great (especially the nice resonant filter) and is still used by many producers today — Norman 'Fatboy Slim' Cook, for example, has two S950s. With a bit of shopping around you can pick one up secondhand for £200‑250.

- Akai S01

Rackmount unit with 16‑bit sampling at 32kHz sampling rate, 1Mb RAM (expandable to 2Mb) divided amongst a maximum of eight samples. Released in 1992 and a touch limited in its features, the SO1 is an absolute doddle to learn and lightning‑fast to use — I love mine! Available for around £120‑200 secondhand.

- Casio FZ1/FZ10M/FZ20M

Keyboard and rackmount samplers working at 16‑bit resolution and sampling rates up to 36kHz, 1Mb RAM expandable to 2Mb. Released in 1987, they quickly became firm favourites of many samplists of the '80s (including Eurythmics' Dave Stewart) by dint of considerable synthesis power, including the facility to draw your own waveforms. Keyboard available secondhand for around £300‑400, rackmount versions worth an extra £50 or so.

- Cheetah SX16

Rackmount unit with 16‑bit sampling at sampling rates up to 48kHz, 512K RAM expandable to 2Mb. 15 outputs available, four‑note polyphony, but no filters. Very basic by today's standards, but still usable as a drum sampler (drum samples are normally small in size) with an output for each sample. Available for £150‑250 secondhand

- Korg DSM1/DSS1

Keyboard and rackmount samplers with 12‑bit sampling at sampling rates of up to 48kHz, 256K RAM expandable to a maximum of 2Mb. Serious synthesis facilities including additive synthesis and user‑definable waveshapes make for great sound‑design, but also for long‑winded programming. You could find one of these machines for anything over about £250, but it's worth paying out extra for one with the DSS‑MMRK upgrade, which upgrades the slow floppy drive, adds a SCSI port and upgrades the memory to its maximum.

- Roland S50/S330/S550

Keyboard and rackmount samplers with 12‑bit sampling at rates up to 30kHz, 512K or 1Mb RAM. Celebrated for warmth of sound, powerful synthesis facilities and the option to add a monitor for more comprehensive display. Secondhand prices vary between £200 for a heavily gigged S50, up to £350 and above for an S550 in good nick.

- Roland W30

Keyboard workstation with similar sampling capabilities to those provided by the S330, along with a sequencer to rival the Roland MC500. It has achieved a certain amount of fame in the last few years as a favourite of The Prodigy's Liam Howlett, but this won't have helped bring down the secondhand price, which could be £350‑500.

The Roland S330's warm sound and powerful synthesis help make up for its limited RAM.

Sample Sites

<!‑‑image‑>Here are a few of my favourite sample‑download sites, which between them must offer more samples than any of us can possibly find time to audition:

- www.analoguesamples.com

No prizes for guessing the theme of this site, which contains samples of virtually every classic synth. Samples are available to download as WAVs, with RealAudio previewing to make choosing your downloads easier. - www.dancetech.com

- www.findsounds.com

A well‑designed and comprehensive search engine for finding all manner of samples and sound effects. Type in the style or name of the sample you're looking for, choose the file type, sample rate and maximum file size and hit Go. - (Empty Reference!)" target="_blank

- hem.passagen.se/lej97/kalava" target="_blank

- www.phatdrumloops.com

- www.samplearena.com

Nice dance‑music site with a good links section, featuring over a hundred sample sites and plenty of original drum loops and synth phrases to download in WAV format. The site also sells it's own range of sample CD‑ROMs. - www.samplecity.net

Another dance‑music site with a good selection of zipped WAV files. Sounds on offer include basses, drum hits, loops, percussion and samples posted by other artists. The site also has tutorials on a host of production techniques, such as tempo matching. - www.samplenet.co.uk

- www.samplelibrary.net

- www.soundcentral.com

- www.synthzone.com

Although not strictly a sample site, this is the place to start when trawling the net for information on all things to do with sampling and music production. Well written and nicely laid out, with one of the best selections of links you'll find on the web, this site should be on your favourites list.

<!‑‑image‑>