Does AI threaten to put us all out of our jobs — or will it simply make us better at doing them? We talked to the developers leading the AI revolution in music.

Artificial intelligence is making an impact almost everywhere. Self-driving cars and virtual assistants are promising to revolutionise everyday life, and music production is also a fertile area for research. So what does AI have to offer music producers, and is it a boon or a threat to people who make music for a living? To find out, we interviewed some leading experts in AI music production. Their responses offer a fascinating insight into how current research and developments could change how we produce and listen to music in the future.

What Is Artificial Intelligence?

Conventional computer software such as a digital audio workstation or plug-ins consists of a set of instructions created by a computer programmer. These instructions interpret the data and user input we provide when interacting with the software, and the software calculates a set result. For example, when we use a compressor plug-in to process a vocal recording, the plug-in responds to our settings and to the dynamics of the material in a predictable way. This can be very useful, but its effectiveness depends entirely on how we set up the compression parameters. A different vocal recording might require a different compression ratio, or indeed a completely different processing chain. Beyond providing presets that we can try out, conventional software can’t help us make this decision. Instead, we draw upon our own past experiences and learned skills to decide the settings for the new vocal recording.

Potentially, an AI compressor algorithm could analyse a particular vocalist’s performance, compare it with a library of other performances and generate appropriate compression settings.Artificial intelligence software could emulate these cognitive skills. Rather than simply offering a dial for the user to set compression ratio, an AI-based compressor could figure out for itself what the best setting might be. Through the analysis of large numbers of existing vocal recordings, the software would build up a mathematical model of what ‘good vocal compression’ sounds like, and apply this model to new recordings by comparing them with the patterns it has learned, this setting the compressor on the basis of its own learned experience, rather than ours.

Potentially, an AI compressor algorithm could analyse a particular vocalist’s performance, compare it with a library of other performances and generate appropriate compression settings.Artificial intelligence software could emulate these cognitive skills. Rather than simply offering a dial for the user to set compression ratio, an AI-based compressor could figure out for itself what the best setting might be. Through the analysis of large numbers of existing vocal recordings, the software would build up a mathematical model of what ‘good vocal compression’ sounds like, and apply this model to new recordings by comparing them with the patterns it has learned, this setting the compressor on the basis of its own learned experience, rather than ours.

In our scenario, the user simply wants the vocal to be more consistent in level. AI software could apply its model learned from earlier vocal recordings to automatically adjust the compression ratio, threshold and other settings, without requiring the user to apply his or her own past experience, learned skills or decision-making.

This is a modest theoretical illustration of how computing concepts such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data could offer new possibilities. These computing concepts are equally applicable to many other music production scenarios, and could profoundly change how we produce music. In fact, AI is already having a significant impact in areas such as mastering and composition.

You Hum It, I’ll Tap It

Tamer Rashad is founder and CEO of Humtap.Tamer Rashad is CEO of Humtap, who have invested 100,000 hours of R&D with musicologists, artists, record companies and producers to develop AI algorithms for their eponymous iOS music production app. As Tamer explains, “Humtap listens to your voice and turns your hums into songs in the style of your favourite artist, in seconds and on the fly on your mobile phone.” The app records your hummed melody and chosen rhythm and applies AI algorithms to compose, arrange, perform and produce an instrumental track — all you need to do is hum your tune and select a drum track on your iPhone’s screen. You can even choose a musical genre, such as Depeche Mode or Metallica.

Tamer Rashad is founder and CEO of Humtap.Tamer Rashad is CEO of Humtap, who have invested 100,000 hours of R&D with musicologists, artists, record companies and producers to develop AI algorithms for their eponymous iOS music production app. As Tamer explains, “Humtap listens to your voice and turns your hums into songs in the style of your favourite artist, in seconds and on the fly on your mobile phone.” The app records your hummed melody and chosen rhythm and applies AI algorithms to compose, arrange, perform and produce an instrumental track — all you need to do is hum your tune and select a drum track on your iPhone’s screen. You can even choose a musical genre, such as Depeche Mode or Metallica.

Many high-profile artists are collaborating with Humtap’s software developers, new genres are being continuously added and the algorithms are evolving. AI-created vocalists are some way off, although Tamer hasn’t ruled this out in the longer term, and an Android version is being developed. Tamer predicts a future whereby anyone without musical training, studio equipment, financial resources or access to music producers can produce an album — potentially within seconds, rather than a year. AI will do the production and mixing for you, all for the cost of a smartphone.

Master Class

Several companies already offer online automated AI mastering services. LANDR’s AI-powered mastering engine ‘listens’ to your unmastered song, identifies the genre and applies relevant mastering equalisation, multiband compression and other processing, all without human intervention. The processing is adaptive, responding to the needs of the song by continuously tweaking the EQ, compression and other processing tools throughout the track. Each time LANDR masters a track and listens to new music, the better it becomes, thanks to self-learning algorithms.

Pascal Pilon from LANDR claims: “We’re mastering a huge variety of music at a very professional level. LANDR has reached a point where it’s difficult for even professionals to know if a song has been mastered by a real person or by LANDR directly — we’ve reached a very high level of sophistication over the last four years. Right now we do over 330,000 songs a month, and if you think about it, that’s more songs than all studios in America combined. It’s really meeting the needs of a large community of artists.”

LANDR has established itself as a viable mastering option, especially for those who are not in a position to pay a human mastering engineer to work on their tracks.

LANDR has established itself as a viable mastering option, especially for those who are not in a position to pay a human mastering engineer to work on their tracks.

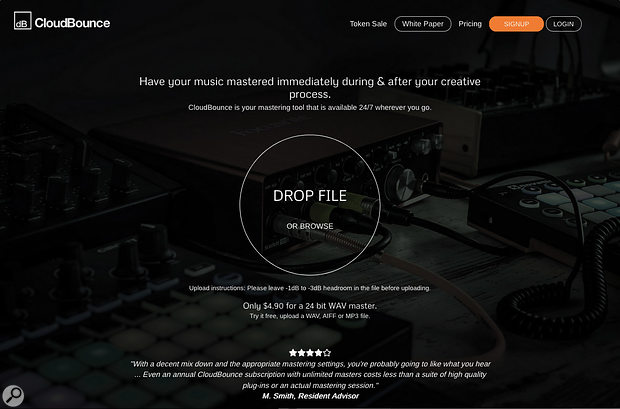

CloudBounce also offer an AI mastering service, and recently published a white paper forecasting their future vision for AI-supported mastering, audio restoration and music production. Anssi Uimonen from CloudBounce points to the staggering volume of material uploaded to social media and video-sharing web sites: 300 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute, and social media platforms such as Facebook are also hosting vast amounts of video content, typically with unprocessed and suboptimal audio.

Anssi Uimonen of CloudBounce.The potential market for audio restoration and optimisation is enormous and growing. Anssi says that his aim is to “build a robust, open network for AI audio production, enabling all content creators to make their videos, music and speech content sound the best it possibly can, automatically”. CloudBounce illustrate this idea by asking us to think of a content creator who records a video using her iPhone; the content is great, but the level is too low and there’s room reverberation. Although she doesn’t have the skills or budget to pay for a professional, she uses AI tools to quickly optimise the audio quality so the content can be published online.

Anssi Uimonen of CloudBounce.The potential market for audio restoration and optimisation is enormous and growing. Anssi says that his aim is to “build a robust, open network for AI audio production, enabling all content creators to make their videos, music and speech content sound the best it possibly can, automatically”. CloudBounce illustrate this idea by asking us to think of a content creator who records a video using her iPhone; the content is great, but the level is too low and there’s room reverberation. Although she doesn’t have the skills or budget to pay for a professional, she uses AI tools to quickly optimise the audio quality so the content can be published online.

It may become second nature for content creators to drag and drop audio files onto AI-powered software, or use online services to quickly remove background noise, unwanted room reverberation and audio artifacts without any user involvement. With this volume of content there simply wouldn’t be enough human audio engineers to go round.

CloudBounce began as an automated mastering service, but is evolving into a more ambitious AI-assisted music production space called dBounce.

CloudBounce began as an automated mastering service, but is evolving into a more ambitious AI-assisted music production space called dBounce.

AI Production Values

AI is thus already opening up new markets by automatically mastering, restoring and optimising audio that would otherwise not have been processed. However, the CloudBounce white paper goes significantly further, and the company are seeking to open up their current cloud-based AI processing engine into a new “community-driven ecosystem” known as dBounce.

The team’s long-term vision is to provide an online platform for AI-supported music production services. In time, the white paper envisages that users will be able to call upon AI services within dBounce to help with pretty much any music production task, including composition, mixing and mastering. As a user, you will work with dBounce as your AI ‘audio producer’, applying multiple algorithms to perform specific audio production tasks. These algorithms will progressively learn to understand different musical genres, and thus to make choices that will be sympathetic to your style. The automated EQ, compression and reverb settings that dBounce applies to your drums could thus sound very different depending on your musical genre.

A seasoned music producer could become part of this community ecosystem by teaching the dBounce algorithms specific audio production skills, such as how to EQ drums for a specific genre, for example Scandinavian folk. Other users could then rate the quality of this EQ algorithm, so the dBounce community contributes real-world feedback on the sources from which dBounce is learning, as part of the trusted ecosystem. Community members who create the dBounce AI audio producers will be rewarded through tokens when their algorithms are used, which can be traded for other dBounce AI audio production services.

Users can also build dBounce algorithms by uploading audio libraries for “feature detection” to train the machine learning models, and evaluate or rank the quality of the resulting algorithms to ensure high quality. This “call to arms” will reward users with their own trusted profile within the community and tokens to purchase other AI services. The dBounce community ecosystem could also provide a platform for plug-in manufacturers to draw upon “AI audio producers” to quickly perform production tasks such as mixing, so users could focus on other creative areas.

Dr Michael Terrell points to mastering as the “low-hanging fruit” of AI audio production, which requires little human interaction. The future road map for AI audio services is likely to become increasingly sophisticated and tailored to many different areas. Anssi adds that “Within five to seven years we are starting to see some really scary things that are very advanced in terms of production and getting the initial idea... or even getting your initial ideas on composition, based on behaviour and stuff that’s been learnt by the machine.”

The dBounce white paper also offers other examples of the ways in which ‘functional’ aspects of audio production, such as removing unwanted noise or ambience, could become automated. For example, content owners such as broadcasting companies may need to update the audio quality of their back catalogue to modern-day broadcasting standards. AI could quickly optimise this audio material, without the broadcasters needing to invest thousands of hours in repetitive manual tasks.

It seems reasonable to say many of these changes won’t happen overnight, although there’s plenty of ongoing research and development that is steadily introducing AI-supported music tools into our day-to-day lives.

A Partner Not A Replacement

LANDR’s Pascal Pilon.Without exception, all the contributors I interviewed for this feature are passionate about AI as a tool for enhancing, rather than replacing, human creativity. Many of them highlight the ways in which AI can empower people to be creative by automating the more functional aspects of music production, and by side-stepping the need to acquire difficult technical knowledge and skills. LANDR’s Pascal Pilon says: “I think it’s going to become a producer’s world. Anybody with a vision of a soundscape or specific song will be able to design it and make it a reality, without having to learn instruments or needing any dexterity in the process. It’s going to become more about visionaries of music, and I think it can only bring more quality out there.”

LANDR’s Pascal Pilon.Without exception, all the contributors I interviewed for this feature are passionate about AI as a tool for enhancing, rather than replacing, human creativity. Many of them highlight the ways in which AI can empower people to be creative by automating the more functional aspects of music production, and by side-stepping the need to acquire difficult technical knowledge and skills. LANDR’s Pascal Pilon says: “I think it’s going to become a producer’s world. Anybody with a vision of a soundscape or specific song will be able to design it and make it a reality, without having to learn instruments or needing any dexterity in the process. It’s going to become more about visionaries of music, and I think it can only bring more quality out there.”

Tamer Rashad likewise sees Humtap as helping music fans to become active creators, rather than passive listeners, saying that presently “less than 1 percent of the population can currently contribute to music creation”.

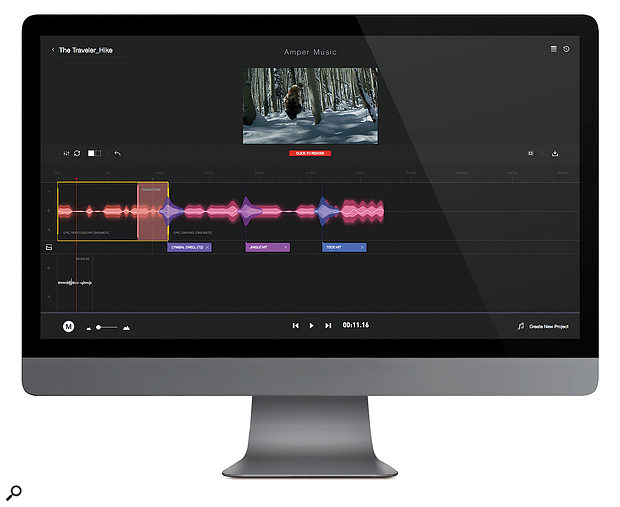

Drew Silverstein is the founder of Amper Music. Drew Silverstein from Amper Music, meanwhile, describes their online service as an “artificial intelligence composer, performer and producer that creates unique professional music tailored to any content in a matter of seconds”. Amper’s goal is to “enable anyone around the world to be able to express themselves creatively through music — regardless of their background, access to resources or training.”

Drew Silverstein is the founder of Amper Music. Drew Silverstein from Amper Music, meanwhile, describes their online service as an “artificial intelligence composer, performer and producer that creates unique professional music tailored to any content in a matter of seconds”. Amper’s goal is to “enable anyone around the world to be able to express themselves creatively through music — regardless of their background, access to resources or training.”

Drew explains: “Everyone has creative ideas. The challenge is not coming up with the idea, it’s figuring out how to express that idea. So if I have an idea for a painting but I’ve never been trained, as soon as I try to brush the canvas it might look terrible. It’s not that my idea was bad, it’s that my ability to express my idea was insufficient.

“If you are a non-musician we are now giving you the superpower, in essence: to be able to turn your idea into reality and to be able to make the content or the music that you’ve always envisioned, but haven’t always had the ability to do.”

Amper uses artificial intelligence to automatically generate a soundtrack to your video.

Amper uses artificial intelligence to automatically generate a soundtrack to your video.

Dror Ayalon, the creator of loop-sharing environment Soundscape, sees AI as augmenting rather than replacing human capabilities. “The AI and machine learning revolution is trying to solve things that we currently don’t do — because we don’t like to do them, or it’s too costly, or because we simply can’t. I think it’s pointless to try and solve things that we already do. The future is basically the combination between human work and the machine. It’s not about replacing the human. Most of the music we love, most of the sounds we love, most of the instruments we love will generally still be in the game. It’s pointless if we don’t do it.”

Social AI

As well as revolutionising existing music-production processes, AI is likely to create new markets for audio production services, as yet unknown. Perhaps surprisingly, a large emerging market is for music fans, rather than solely musicians, producers and online content creators.

Many contributors point to a more connected future, where music consumers use AI music-creation apps to enrich their interactions with others on social media. Non-musicians could create music and collaborate with artists and friends, without any musical training, access to skilled producers, studios or money. This opens up opportunities for anyone with a passion for music, regardless of technical skills, to have a creative musical experience. Fans could propose new tracks directly to their artists, generated through their AI-supported interpretation. Tamer paints a picture of a teenage girl from a village in Africa without access to studio facilities collaborating with her favourite artist using only her smartphone. AI could widen opportunities and level the playing field for everyone.

Empowering everyone to create music and interact through social media is a major growth opportunity. AI turns passive listeners into music creators, bringing consumers much closer to artists. Several contributors draw a parallel with existing content-sharing platforms such as Instagram as the future model for connecting by creating new music, and social media is seen as offering huge potential for AI-produced music.

More daringly, Tamer Rashad suggests that AI could be used to create new tracks by artists who are no longer with us. Algorithms could analyse an artist’s entire back catalogue and identify patterns in the melodies, harmonies, instrumentation and arrangements, then generate limitless new songs inspired by that artist. Reproduction would be instrumental at least for the foreseeable future, although AI-created vocalists are seen as feasible in the longer term. Once again, all you would need is a smartphone.

What About Music Producers?

The benefits of automating repetitive, non-creative ‘functional’ activities are not only relevant to non-musicians but also to seasoned producers. As Dr Michael Terrell says, “When you start a new project there’s tons and tons of stuff you do that’s similar every time but not exactly the same. There’s all these functional aspects that, if you have AI tools to assist, could probably shave off 50 to 70 percent of the time it actually takes to mix a track. For those people being paid by the track, it’s a lot to save.”

Songwriters could likewise benefit from genre-appropriate, AI-suggested instrumentation or arrangements to help get a song over the line quickly — handy when you’ve an impending deadline. They could then use an app like Humtap to create a full demo in their desired genre and share it with the rest of the band. Musicians without the skills to mix a song could also rely upon AI-supported mixing; rather than having to learn how to use compressor controls such as ratio, threshold and release, you could simply say you want the vocals to be louder and more consistent, or that the guitar needs to be more prominent than the piano.

Tamer Rashad also suggests that AI could help artists redevelop their music in alternative genres, to reach a new audience. For example, an American pop artist could draw upon AI to regenerate an existing track in a Bollywood style.

Soundscape aims to further human creativity by pairing the musical content created by producers around the world.

Soundscape aims to further human creativity by pairing the musical content created by producers around the world.

AI also has an important role to play in fostering collaboration between human musicians, and this is the core aim of Dror Ayalon’s upcoming online service Soundscape. Soundscape automatically matches your musical ideas with those other musicians: you record a loop, which Soundscape analyses and synchronises to a comparable musical recording from others around the world, evaluating how closely your music style matches theirs. All you need is a single click of your mouse button and Soundscape makes the connections.

Dror Ayalon, inventor of Soundscape.You can then mould shared loops into your own music, just as others can with your musical phrases. Dror explains his motivation for Soundscape: “I was always in search of new ways to get people closer to music-making and closer together. I felt that the ability to sync people’s loops automatically is just giving me an echo that there is someone out there playing something that is as weird as maybe what I play. Maybe it’s harmonics to what I play, maybe there are other people who are doing the same thing.”

Dror Ayalon, inventor of Soundscape.You can then mould shared loops into your own music, just as others can with your musical phrases. Dror explains his motivation for Soundscape: “I was always in search of new ways to get people closer to music-making and closer together. I felt that the ability to sync people’s loops automatically is just giving me an echo that there is someone out there playing something that is as weird as maybe what I play. Maybe it’s harmonics to what I play, maybe there are other people who are doing the same thing.”

Dror summarises his experiences of connecting with others as “this fascinating moment of not feeling alone — you, your guitar, your amp at home — was something that I felt I’m really interested in. Since this is the case, your results are always surprising.”

A Little Knowledge

AI may also change the tools with which music producers do their work. As Dr Michael Terrell points out, digital audio workstation software and plug-ins are often modelled upon analogue ways of working, with a mixing console and long-established types of processing such as compression and EQ. AI raises questions around our current way of interacting with DAWs. Will the analogue metaphor make way for radically different interfaces and interaction styles? Dr Terrell points to his research, which involves automating mundane tasks such as setting level balance and basic panning and EQ in order to allow musicians to focus on being musicians. He adds: “My main motivation was to build a tool that would help people to mix music well, having seen lots of friends who really struggled to do it. One of the issues around mixing is that it’s just quite complicated. You need a good technical understanding of what the audio processors are doing, you need reasonably good versions of those tools, you need decent ears, you need a good setup at home, and it’s just very, very difficult to do.”

Dr Michael Terrell is one of the researchers behind dBounce.Dr Terrell suggests that AI tools could, in effect, act as an interface between the user and the standard DAW toolset. “An AI interface could offer simple controls that would help you mix something that actually sounded better than it would have been if you tried to do it yourself, in a lot less time. With all these tools you can build a hierarchy of controls where, right at one end, you have full automation, and as you step up, you’re effectively providing more intricate controls, but through far easier-to-understand interfaces. So, when you’re using a compressor, you have all these weird controls — you know attack, release, threshold, ratio. When you try to explain to someone what that’s doing, it’s not simple. AI could enable musicians to say what they want as an outcome, such as ‘I want to sound a bit louder’ or ‘a bit more consistent’. That way, you’re allowing people to control the software using an interface that they can easily understand.”

Dr Michael Terrell is one of the researchers behind dBounce.Dr Terrell suggests that AI tools could, in effect, act as an interface between the user and the standard DAW toolset. “An AI interface could offer simple controls that would help you mix something that actually sounded better than it would have been if you tried to do it yourself, in a lot less time. With all these tools you can build a hierarchy of controls where, right at one end, you have full automation, and as you step up, you’re effectively providing more intricate controls, but through far easier-to-understand interfaces. So, when you’re using a compressor, you have all these weird controls — you know attack, release, threshold, ratio. When you try to explain to someone what that’s doing, it’s not simple. AI could enable musicians to say what they want as an outcome, such as ‘I want to sound a bit louder’ or ‘a bit more consistent’. That way, you’re allowing people to control the software using an interface that they can easily understand.”

Drew Silverstein from Amper Music continues the theme of AI offering simpler tools. “Those [DAWs] are complicated. They take time and skill to learn, which speaks of the immense power that they hold — they’re complex for a reason. For individuals who are used to using those pieces of advanced technology, Amper’s not going to replace them. Amper is going to be a collaborative tool and a creative partner to help [people] further their existing music-making in the same way that the DAW did for them 20 years ago. Amper will do the same thing. You’ve got a whole population of individuals who look at a DAW and say it’s too much. We’re not saying ‘Let’s get rid of that knowledge and expertise as a prerequisite to be able to express your creative idea.’ If you use a DAW, great. You’ll probably be able to get more out of Amper than anyone else would, or you’ll be able to go further. But you’re not required to.”

It seems reasonable to summarise that as algorithms become more widely available, AI may enable us to define the level of control we want over our production. We can still have lots of complexity and flexibility if we want it, but we can also choose easier and more immediate results, albeit with more decisions made for us. AI could become like a human engineer who quietly sets things up and helpfully manages the technology for you, so you can focus on the music.

As Dror Ayalon says, “If you think about it, for many years, the industry emulated analogue instruments in a digital environment. The basic reason behind that was to reduce cost on one hand and to be able to do things on a massive scale. I think that people are starting to understand now that we’re not actually composing music, we’re composing data. We basically produce data pieces, but this data is artistic data that we can actually change minds and lives with — so I think you will see software starting to build tools and interfaces that will allow musicians to actually interact with that. I believe that you will be able to find tools that are heavily rooted in artificial intelligence in any studio and on the phone of any artist. I believe this age is coming real soon.”

Maximum Creativity

If AI can, hypothetically, produce an album in seconds, does this mean that musicians and producers will be out of a job, and that there is no longer a role for human creativity? That’s not the way our interviewees see it. Without exception, everyone we contacted loves human involvement in music creation. As Pascal Pilon says, “For us at LANDR, it’s essential that when we talk about the AI, we always carve the creative aspects out of the equation and leave them in the hands of the artist. We see ourselves empowering artists to make creative decisions and we focus on taking the technical elements out of the equation.”

Dror Ayalon, the creator of Soundscape, describes AI as a tool to improve musical creativity: “If these algorithms create something that is not interesting — that sounds exactly like the Beatles, or exactly like hip-hop hits from last year — they won’t succeed and get enough attention. So it’s about giving creative tools to people to make innovative music on one hand and, on the other hand, using algorithms to generate synthesized new music in the most creative way possible. No-one in the field that I know about is in it just to replicate something that was done before. Every one of us is excited about the vision, excited about creativity, and if artists and sound engineers won’t adopt what we’ve built, we failed. So [we’re] working with these people to understand how can we help them do what they do. We’re not looking to replace anyone, but build tools that can make them do amazing things. Most of the innovation that we saw in music production in the past came from innovative tools, from innovative synthesizers to innovative acoustic instruments to innovative computer music. I think there is a big opportunity here for something that is dramatically different that could change the convention about how we make, how we mix, how we produce music. I believe that I can say the music production and music composition industries are looking for such innovation.”

Drew from Amper Music adds: “Regarding the concern around diminishing creativity, I think that is an argument that some would make without looking at the whole picture, because, arguably, the fact that people now can produce something or make something without knowing how to perform and write for every instrument and perform with live players already kind of does that. We’ve just accepted the current standard as OK, but it’s the fact that a kid in his bedroom can now make a beat or a hip-hop loop or a song without knowing so many things that, 100 years ago, we would have said ‘If you don’t know this, you are not creative.’ Evolution is an unstoppable part of humanity in any field.

“I would actually argue that even today the bar to create music and produce music is quite low, and doesn’t necessarily require any skill. At one point hundreds of years ago, to write and create music you needed to know music theory and to have a pen and paper. You had to be a church musician or have a sponsor. Now, if you have a cellphone and some rudimentary app you can make music that could be a hit, just because you’ve got technology that requires very little skill or expertise.

“That being said, there is still a world in which the more skill you have and the more training you have, arguably, the stronger your ability to express your idea creatively would be. As technology advances, the technological bar necessary to express yourself drops considerably. We went from pen and paper to magnetic tape to digital to mobile — every time we do that it gets easier and easier to take your idea and turn it into reality. As a consequence, the skill set and the ability to actually do that becomes more and more democratised, and so more and more are able to join the creative class whereas they previously weren’t able to.”

Dr Michael Terrell makes the point that “One of the big reasons people make music is that they like making it. It’s not some task that you want to farm out to AI, it’s something that people actually enjoy. So what you end up doing when someone wants to do something creative like that is you build tools that help them do that more effectively. So I think this idea that it reduces creativity is actually wrong. It’s the opposite. It should free up people to actually be able to make the music they want to make, without these technical burdens that are a big limitation for a lot of people.”

AI & Careers

So how will this affect people who make their living from music production? Pascal Pilon: “When we launched this thing [LANDR] our slogan was that we work for musicians. Our view was never to prevent engineers from making a living. What we looked at was that over 95 percent of music creators could not afford the service of mastering engineers. Even those that could afford mastering engineers, would only do so now and then, for example for one album a year instead of every creation. What we believe is that every time someone creates audio, it deserves to be delivered and finished with a fighting chance, so people can look at it and say ‘Hey, there is something in there that I think I can work on and improve. It’s just ready to be shared with the people that I like.’

“I think there’s a lot mastering engineers out there who are very, very good, and who are also acting as producers in their approach. They revisit and direct the overall sound of the mix — and that, to me, is producing. And that’s great. I’m really happy master engineers act as co-producers, in that we’re just bringing productivity to artists, we’re not taking jobs. So I don’t think there’s going to be less sound engineering jobs with LANDR around. I think there’s just going to be more music. I think that’s great.”

Dr Michael Terrell talks about future opportunities for professional producers to train dBounce to become an AI audio producer. “One of the things we’ve tried to do with the design of this ecosystem is that if you’re a music producer and you’re very good, you will still be — you can actually take part in this ecosystem. If you can train AI and you own it, you can earn money from that AI, so it becomes an ancillary revenue stream. If you can dump all your AI knowledge into a machine and then earn the money from that, you can probably enjoy your life doing whatever you want to do. So it’s about getting involved with the ecosystem.”

Drew Silverstein from Amper Music again draws an analogy with earlier technologies. “When the synthesizer came out, everyone worried that there would never be another live musician ever again. Orchestras are still around, and some are thriving more than ever. Depending on what area you put yourself in, there’s always going to be this existential concern about the future. What we’ve seen is that for those who take advantage of the opportunities provided to them by advancing technology, the future in some ways is never brighter.”

Drew draws a distinction between artistic and functional music. “We look at media music in two different buckets. One we call artistic music and one we call functional music. Artistic music is valued for the collaboration and creativity that goes into making it. It’s about the creative process of working with another person to make art that’s artistic. Our perspective is that that will never go away, even when Amper and AI music is indistinguishable from human-created music. This is because the value is not about the final product, it’s about the process of making it. It’s about [John] Williams and [Steven] Spielberg sitting down and scoring the next Star Wars. It’s that artistic mind-melding of multiple individuals making art.”

Functional music, by contrast, is “music that exists in a world where it serves a purpose — but no-one gets in an elevator and asks about the music, what it’s doing and why it’s there. Functional music is valued for the purpose that it meets, but not for the creative process that went into making it. In those situations individuals who [need] functional music often have creative ideas themselves — musical ideas. We aim to help them directly turn their idea into reality.

“And so what I say to people who are concerned about jobs is a couple of things. One, your job in five years will probably not exist. Your career certainly will, and it’s important those two things don’t get separated out of context — because otherwise it can make me look terrible when I don’t intend it to be! What I mean is the way that we make a living in music has changed for all time as technology advances. As long as we’re able to adapt to the advances and to take advantage of what technology offers us, then we’ll be able to continue providing value to others. We’ll be able to keep our career, but that doesn’t require that our job remains the exact same, because it’s not and it shouldn’t be. If it was then where would progress be? We would be stuck in whatever era you want to define as the era we should be stuck in. So part of the negative reaction to this evolution is fear based on an uncertainty within which an individual exists: ‘I’ve spend my entire life trying to do this thing. What happens to me in this future that as of now is very opaque, and because of that, is very concerning to me.’”

Drew adds that “while Amper will change the future of music, it won’t replace it. As long as an individual is creating music which is valued artistically that is delivering value to whoever it is — whether that is a listener or a client or creator — in the way that they need value to be delivered, then humans will be able to create and make a living from music or other art for all time.”

Similarly, it seems plausible that the best producers will always be in demand. It looks likely that AI will not replicate all the interactions and deep working relationships between artist and producer any time soon. In essence, people like people.

Too Much Music?

If AI apps empower everybody to generate music, is there a risk that great music will simply become lost in huge amounts of online content? Pascal Pilon compares music with video content: “If you think about the quality of lenses today and what people are using from their phones, there’s a ton of pictures being taken and there’s a lot of videos being made. Are we saying that there are too many videos? Not so much, we have the attention span that we do. YouTube is full of videos, and we watch what we want to watch. I think music is becoming something we access via recommendations from friends and people. I think the way we navigate the offering will change.”

Pascal also points out that AI tools can help navigate the flood of music, helping us to find artists to listen to or work with. “In terms of sounds that you’re looking for, in terms of collaborators you want to work with, in terms of listeners you should be listening to, I think AI will make that process very efficient. Making music and getting heard will become more like posting on Instagram and getting followers. Everything’s going to be residing more on social networks, and I think the music landscape will trend towards the image landscape — very fragmented, very wide. You’re still going to be able to buy professional photography at $20,000. That hyper quality will still be featured in a certain way, but listeners’ tastes will prevail. I don’t think that it matters if there’s five million songs or five billion songs out there. I mean most of those songs will be only important to the artists themselves and their immediate relatives. The best will stand out, and the methods by which we find them will be very exciting. Our relationship to music will be more social-media based, as will our response to music.”

It’s Up To Us

The future is likely to see an explosion of new music created by people who previously did not have the means to do so, enabled by AI-based tools. Equally, musicians and producers are likely to find more time to be creative and to create music in new ways, leaving AI to manage repetitive functional tasks. Creating music is likely to become part of people’s online interactions, with consumers creating and sharing new music through social media platforms.

AI for music production and consumption is a huge area, and this article can only offer a flavour of ongoing research and development for AI music services. As Cliff Fluet puts it, “AI is going to become a term that’s as helpful as talking about ‘the Internet’. Twenty years ago, if I’d tried to describe the Internet, you would think it was just one platform — and actually it was the first step to something huge.”

The rich opportunities around AI raise many questions, and to date, we only have some answers. Many developments are in their infancy and some timings remain uncertain. What is certain is that AI is receiving serious attention from major record labels, number one artists, business incubators and leading-edge software developers, so changes are on their way. Many contributors estimate we’ll start to see a shift in music production and consumption within the next five to seven years. Widespread adoption will come down to how easily we can interact with our AI tools and the quality of the end results, which are steadily advancing.

As with any emerging technology, we clearly have a choice about whether to use it and how we want to use it, and it may be the market that shapes the direction of AI software. All of our contributors were keen to emphasise that AI will not replace artists or producers. Paradoxically, the more we use AI within music, the more we may draw people together.

The Future Of The Music Business

If AI changes the music-industry landscape, how might industry bodies such as major record labels respond?

Cliff Fluet of media advisory firm Eleven.Cliff Fluet, Managing Director from media technology advisory firm Eleven, says: “Because there are so many different types of AI music tools, the response from major labels really depends on what the technology is and what it does. To shape-shift [change the genre of] tracks or make them adapt or remix them at a vast speed is extremely interesting to them. These are tools that make what was a very manual, costly and laborious process fast, cheap and efficient. In a world where everything’s run by streaming web site playlists, they can potentially create a version of a song for every genre — to have a version in every playlist, that’s money for them. For sync, labels make a lot of money from using music in ads and for brands, so AI technology that adapts existing recordings more easily is also popular.

Cliff Fluet of media advisory firm Eleven.Cliff Fluet, Managing Director from media technology advisory firm Eleven, says: “Because there are so many different types of AI music tools, the response from major labels really depends on what the technology is and what it does. To shape-shift [change the genre of] tracks or make them adapt or remix them at a vast speed is extremely interesting to them. These are tools that make what was a very manual, costly and laborious process fast, cheap and efficient. In a world where everything’s run by streaming web site playlists, they can potentially create a version of a song for every genre — to have a version in every playlist, that’s money for them. For sync, labels make a lot of money from using music in ads and for brands, so AI technology that adapts existing recordings more easily is also popular.

“There is much excitement, but a certain hesitation to ask incumbent labels to embrace pure generative AI. There’s Upton Sinclair’s quote — “It is difficult to get a man to understand something if his salary depends on not understanding it” — and that very much is applicable to generative AI music. If you live in a world where musicians and/or A&R people felt that a machine could just create a performance... one might say they’re intellectually invested in not taking it up.

“Taking the long view, because I’m really, really old... I’ve seen all this before. There was word in the ’70s that synthesizers meant there would be no more pianists or keyboards, or drum machines meant no more drummers. There was then a word that music sampling would destroy music, or that putting digital music online would mean the end. Not only did none of those things turn out to be true, but the exact opposite turned out to be true.”

LANDR’s Pascal Pilon points out that “The music industry is a laggard in many aspects. Look at the financial market and how start-ups around the world are seeking financing to develop and commercialise products with the assistance of venture capital partners. In the music industry, this role has been played historically by the record label, but sourcing a deal with labels is still very rudimentary. I think the music industry’s financing model will progressively become more data-driven, more competitive. It will draw more capital from a wider set of investors, still involving labels but also a larger set of small to large angel investors.”

Pascal predicts that music labels will still need to invest heavily in talent to promote music. “Even if there’s AI, you will still need people to bring artists visibility. Think marketing: the rarest thing you get is listeners in the music space that spend. Your ability to bring people to listen to you will still require a cast of collaborators from a marketing perspective. Again, it’s very similar to the movie industry. Look at how important the production budget is — yes they’re huge, but think about the commercial budget, which is even bigger. To gain people’s attention, you will need to spend on channels to deliver that — think Facebook. If you can bring virality to the likes of Google and YouTube then you will be able to be independent, but it will require lots of sophistication from a promotion standpoint.”

AI & Copyright

Who owns music that is generated by artificial intelligence? And if AI software can be inspired by existing songs and generate new music of a similar style, does copyright become a grey area?

Like every new area of technology, AI promises to generate plenty of work for lawyers.Cliff Fluet of media advisory firm Eleven insists: “It’s not grey at all. It’s that people don’t like to hear the answer, depending on what they’re doing. But you’ve asked the key question and there’s a whole bunch of lawyers speculating on this stuff!

Like every new area of technology, AI promises to generate plenty of work for lawyers.Cliff Fluet of media advisory firm Eleven insists: “It’s not grey at all. It’s that people don’t like to hear the answer, depending on what they’re doing. But you’ve asked the key question and there’s a whole bunch of lawyers speculating on this stuff!

“This is as good or as bad a question as asking who owns a movie. The real answer is that it kind of depends on how you made it, how much of it is yours and how much of the stuff is owned by somebody else. To what extent are you getting the input of actors, set designers, third parties and so on? To what extent did you create something wholly original? The answer is as simple and sophisticated as that really. Every single one is dependent on how their processes, how their algorithms, how their choices are made. If you’re a really good lawyer the answer is very, very simple, provided you really understand the depths of the processes.”

Given that AI for music production is an emerging technology, is this a legally tested area?

Cliff Fluet: “I’d say it is and it isn’t. The law on music copyright has been built upon highly unreliable technology called musicians and the human brain. You’ve got people asking ‘What if a machine replicates something else?’ — and it’s like ‘Well, what if an artist replicates something else?’, which is what happens every single day in the music industry. There’s real questions about did someone actually hear something or did they not? Did someone actually adapt something? The law is not different when it’s a machine or human being. The difference between a human being and a machine is that with a machine you have absolute evidence.”

Cliff points to previous legal cases where “the jury has to sit there and try and work out whether someone heard something, adapted something or did it. With a machine, you don’t have to rely on its memory, you just literally can see all of the notes there, so actually I think arguably it’s easier rather than more difficult. Working out whether or not a human has ripped off a composition or whether or not they own it, or whether or not they shared it, is far, far more complex than a machine. If anything, the advancements in technology could help.”

Try It For Yourself

The services and products mentioned in the main text can be accessed through the following URLs:

- Humtap www.humtap.com

- CloudBounce & the dBounce white paper www.cloudbounce.com

- LANDR www.landr.com

- Amper Music www.ampermusic.com

- Soundscape www.drorayalon.com/soundscape