Star producer Ariel Rechtshaid inhabits many different musical worlds at once. No wonder he’s busy...

As one of the most in-demand producers in the world right now, Ariel Rechtshaid is unusual in the sense that he manages to work very successfully in both the fields of alternative music (Vampire Weekend, HAIM, Cass McCombs) and pop (Adele, Madonna, Usher). The fact that he’s very comfortable operating within either genre can probably be traced back to his upbringing in Los Angeles.

“I grew up listening to lots of music,” he says, “and even though the records you bought were generally the kind of records that defined your identity, something about Los Angeles was driving and listening to the radio. I didn’t necessarily have to buy a Madonna record to hear Madonna, ‘cause it was playing all the time. So I was listening to Echo & the Bunnymen and Prefab Sprout at home and then hearing Madonna in the car. I had this whole wide palette of music in my head.”

Hippo Hops

Rechtshaid’s career effectively began in the early ’90s in his days back at Hamilton High School in LA, where, as a 15-year-old devotee of the Clash and the Specials, he formed his first band, punk-ska outfit the Hippos. On the strength of a demo the band colourfully titled Attack Of The Killer Cheese, they were signed while still teenagers, releasing their debut album Forget The World (1997) on Fuelled By Ramen Records, before inking a deal with Interscope for 1999’s Heads Are Gonna Roll.

It was an intensive education for the singer/guitarist, not least because it provided a crash course in production. “I didn’t even understand what a producer was,” he admits. “I couldn’t articulate why I liked drum sounds on these Specials or Clash records, because to a professional engineer/producer, those records sounded like shit when big ’90s drums were the thing to do. I didn’t understand what a microphone or compression or a room did to a sound or any of that kind of stuff. So at a pretty early age, I started to feel like I had to figure it out because otherwise I was at a loss. I couldn’t make the music I wanted to make.”

After experimenting with a cassette four-track in his bedroom during his mid-teens, Rechtshaid’s experiences in professional recording studios exposed him to Pro Tools, which resulted in him investing in a Digidesign Digi 001 interface so he could learn the program at home on his Mac. At the same time, the Hippos were falling apart, so he decided to pour his energies into teaching himself recording techniques. “I set up a little studio in my parents’ garage,” he remembers. “Sometimes people have asked me, ‘How did you know at 19 that you weren’t going down the path you wanted?’ It was just like a gut feeling that I need to put the brakes on and learn some shit.

“I started to understand how, like, ’70s drums sounded different than 1990s DW drums with clear heads on them. I started realising that, y’know, taped-up dead toms were something that I was into. And my first attempt at that probably sounded pretty lo-fi and shitty. But I remember liking the way that vocals, when a mic pre was overdriven, kind of had a distortion. That was the kind of stuff I was experimenting with.”

My My My, Delilah

Through his contacts with managers and other bands that the Hippos had toured alongside, Rechtshaid began to receive enquiries about his burgeoning skills as a potential producer. This quickly led to him working with emo group Armor For Sleep and indie rockers We Are Scientists and Plain White T’s. It was with the latter band that Rechtshaid scored his first hit, with the 2007 number-one ballad ‘Hey There Delilah’, which had actually been recorded three years earlier at North Hollywood studio Harddrive Analog and Digital.

Through his contacts with managers and other bands that the Hippos had toured alongside, Rechtshaid began to receive enquiries about his burgeoning skills as a potential producer. This quickly led to him working with emo group Armor For Sleep and indie rockers We Are Scientists and Plain White T’s. It was with the latter band that Rechtshaid scored his first hit, with the 2007 number-one ballad ‘Hey There Delilah’, which had actually been recorded three years earlier at North Hollywood studio Harddrive Analog and Digital.

“I remember recording the vocals and the guitar separately,” he says, “trying to make it sound like it was happening live. A very simple Beatles-y/Simon & Garfunkel kind of thing. I left it at that.”

Featured initially on the band’s third album All That We Needed, ‘Hey There Delilah’ became a fan favourite and appeared again (with an overdubbed string arrangement by Eric Remschneider) as a bonus track on their fourth album Every Second Counts in 2006, before hitting the top of the chart the year after. “All of a sudden I started hearing it on the radio and thinking, ‘Is that even the same recording that I did?’” Rechtshaid recalls. “It was such a distant memory at that point. I kind of assumed that they’d re-recorded it. But it turned out that it was the same recording and it came back to life and became a number one.”

Refusing to be pigeonholed, Rechtshaid turned down various offers to recreate the same acoustic-based production formula for other artists. “I did get calls,” he says. “People started to reach out, as they do when they find out that there’s a young producer who’s doing something. And, yeah, I did realise that once again I was sort of possibly heading down a path where I was misunderstood. What happened with me and Plain White T’s was I was in a situation and my instincts led me to that version of the song. I’m proud of that, and the song is a great song. But it’s not that I chose to make acoustic singer/songwriter music. It was more just the approach of how I dealt with the band. And so I realised I needed to try and work on music that felt a little bit closer to home.”

Double Dares

Rechtshaid’s next move was to form a new alternative rock band, Foreign Born, acting as bassist and producer over two albums. During this period he also first met the artist who was to further his production career, Californian singer-songwriter Cass McCombs. Rechtshaid was a huge fan of McCombs’s 2007 album Dropping The Writ, and wondered if together they might try a different, more traditional approach to making his fourth album, 2009’s Catacombs. “At this point we’d all been playing with Pro Tools and the limitless tracks,” he says. “I started thinking, What if we had restrictions? What if we couldn’t go beyond eight tracks? And that way it would be very hard for us to put too much bullshit on the song. We’d have to keep it pretty minimalist.”

Rechtshaid’s next move was to form a new alternative rock band, Foreign Born, acting as bassist and producer over two albums. During this period he also first met the artist who was to further his production career, Californian singer-songwriter Cass McCombs. Rechtshaid was a huge fan of McCombs’s 2007 album Dropping The Writ, and wondered if together they might try a different, more traditional approach to making his fourth album, 2009’s Catacombs. “At this point we’d all been playing with Pro Tools and the limitless tracks,” he says. “I started thinking, What if we had restrictions? What if we couldn’t go beyond eight tracks? And that way it would be very hard for us to put too much bullshit on the song. We’d have to keep it pretty minimalist.”

His idea was to rent a house in the Highland Park area of Los Angeles and ship equipment in. “It was an old Spanish house with big vaulted ceilings and it had options for acoustics,” he recalls. “It was very live-sounding and I could dampen it up, but also there was a natural acoustic to it that seemed like it would be helpful. So we just started kind of daring each other: ‘Let’s try doing this without headphones. Every member of the band has to play quiet enough or hold back enough to hear the other player.’ It wasn’t to try and be retro. It was really just as some sort of limit to what we could do and see how that affected the songs.”

For the project, Rechtshaid bought an Ampex AG440 one-inch eight-track machine and installed it in the house along with some of the equipment he’d collected over the years. “I brought basically eight mic pres, a few compressors, all my microphones, rented a few more microphones and set up in this living room and really experimented for a month. Because we were dealing with eight tracks and I didn’t have a mixer, I would start out with just a kick mic and an overhead on the drums. I miked the room in stereo and then I’d have a mic on Cass. He was playing acoustic usually and so the mic would pick up his voice and the acoustic.

Rechtshaid’s studio also features its fair share of outboard. Left rack, from top: UA Apollo audio interface, Grace Design M905 monitor controller, Furman PL-Pro DMC power conditioner, Neve 1272 and 1073 preamps racked by Boutique Audio & Design, Urei 1176LN compressors (x2), Digitech Vocalist II vocal processor. Right rack, from top: Eventide H949 Harmonizer and SP2016 reverb, AMS RMX16 reverb, API 3124+ preamp, Tube-Tech CL1b compressor, Smart C1 compressor, BAE-modified Neve 2254E stereo compressor and Inward Connections DEQ1 equaliser.

Rechtshaid’s studio also features its fair share of outboard. Left rack, from top: UA Apollo audio interface, Grace Design M905 monitor controller, Furman PL-Pro DMC power conditioner, Neve 1272 and 1073 preamps racked by Boutique Audio & Design, Urei 1176LN compressors (x2), Digitech Vocalist II vocal processor. Right rack, from top: Eventide H949 Harmonizer and SP2016 reverb, AMS RMX16 reverb, API 3124+ preamp, Tube-Tech CL1b compressor, Smart C1 compressor, BAE-modified Neve 2254E stereo compressor and Inward Connections DEQ1 equaliser.

“When we needed to do an overdub I’d kind of get a balance going, take a shot of whisky and then bounce it down. It was very destructive, y’know. No going back, no undoing. It was really, really fun. That was my first real experience with tape — splicing tape, cutting it back together, it was cool.

“It’s amazing how much you can get done in a month when you’re just tracking the songs live. We must have recorded 40 songs, with maybe like five or six different arrangements on each song in that time. And then brought the tape machine back to my house afterwards to mix it [to two-track tape]. We started out on an Ampex 351 but it was just too crazy and breaking down every five seconds, and it led me to buy an [Ampex] ATR-102.”

Pop Up

Rechtshaid went on to make another two albums with Cass McCombs, Wit’s End and Humor Risk, both released in 2011. But then his career took its perhaps surprising diversion into the world of pop. The bridge was his production of British musician Dev Hynes’s debut album under the name of Blood Orange, Coastal Grooves, which found Rechtshaid being approached to work with the likes of Sky Ferreira, Solange and Charli XCX.

“At that point I had been doing bands for some years and I wanted to try some other things,” he says. “It wasn’t that I was trying to do pop music, ’cause I never thought of myself as someone who would do, like, the Backstreet Boys or something. But the genre lines seemed to be blurring and things were changing and evolving.”

In some ways however, Rechtshaid’s move into more electronic-based productions wasn’t an entirely unexpected development, since in 2003 he’d ended up reuniting with his ex-high school friend, rapper Murs, to work on his first release on Definitive Jux Records, The End Of The Beginning. Through this, Rechtshaid soon made other connections in the hip-hop recording world. “I met J-Swift who produced the Pharcyde,” he remembers. “He was showing me the synthesizers and the microphones that hip-hop guys liked to use. The [AKG C]414 on everything, and the [Roland] Juno 60. That was his thing and, of course, sampling.”

Rechtshaid was subsequently introduced to Bruce Forat, the former Linn Electronics tech who bought the company’s assets after the company went out of business in 1986. At the time the young producer first met him, Forat was renowned within the hip-hop community for his modifications to the MPC. “In the ’90s he became the MPC guru,” says Rechtshaid. “Everybody sent their MPCs to him to get modded out. I remember getting a Zip disk installed in my MPC, and it was so futuristic ‘cause I had 25MB worth of information instead of 5MB! You’d go to Forat and you’d be like, ‘What’s that?’ And he’s like, ‘That’s an Emulator, that’s all over the Depeche Mode records.’ And then I’d play it and be like, ‘Holy shit.’ I was really absorbing a lot of information.”

Hero Worship

Another key connection was made when Rechtshaid met Thomas Wesley Pentz, aka Diplo, the former DJ turned producer who’d already enjoyed successes with MIA, Drake and Snoop Dogg. Their first major collaboration was their co-write of Usher’s ‘Climax’, the atmospheric 2012 R&B hit which Diplo accurately described as a blend between Radiohead and the mellow soul genre quiet storm.

Another key connection was made when Rechtshaid met Thomas Wesley Pentz, aka Diplo, the former DJ turned producer who’d already enjoyed successes with MIA, Drake and Snoop Dogg. Their first major collaboration was their co-write of Usher’s ‘Climax’, the atmospheric 2012 R&B hit which Diplo accurately described as a blend between Radiohead and the mellow soul genre quiet storm.

“Wes got asked to go and work with Usher, and he asked me to come with him and I was like, ‘Fuck yeah!’” Rechtshaid laughs. “All I could think of was high school and all the girls looking to Usher. Without owning the records, I knew them all. So I started doing my homework and relistening to them and, of course, you just get blown away. I started getting ready for it and just tried to imagine what might work for Usher.

“We go in there and I’m getting my confidence up. I have all my chord changes and drum sequences in my head that are Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis-esque, who are my heroes by the way. And as I’m walking into the room, no shit, the door opens and they’re walking out. It was just this moment of my heart dropping. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve made a serious mistake here!’ Of course, if he wanted that, he would ask them to come in. And he did.

“But he called Wes and I in there to do what we do. It was tense at first, ’cause there’s a lot of people around. Usher was really nice but there’s an energy of, like, ‘What have you got? What are you gonna do?’ You could be out just as soon. And so I started playing him stuff. Wes and I would share little bits of sounds and little sequences that we’d have in folders, just playing stuff and watching him and reacting.”

Rechtshaid remembers Usher’s eyes lighting up when he played him the sketch of the track that was to become ‘Climax’. “I remember the little electronic sequence that starts out on ‘Climax’ came on, and then the beat went four on the floor, and he was kind of like, ‘Yeah.’ We had three days with him, so I just held onto that moment where I saw him light up on that little synth sequence.”

Although the rough was originally a faster dance track, Rechtshaid took the decision to cut the tempo to half time. “We brought in some drum MIDI from a different one of Wes’s songs. I remember it was firing off the wrong drum sounds — the hi-hat was actually a snare drum just pitched way up. I just started playing chords around the drone, essentially, and then his executive producer came in and was like, ‘Ooh, Usher’s gotta hear that.’ He came in and heard it and just started singing this incredible falsetto. Y’know, I had never been in the room with anyone who could sing like that. So I was like, ‘That let’s do that.’”

Ariel Rechtshaid’s studio-cum-storage-facility is based in Burbank, LA.

Ariel Rechtshaid’s studio-cum-storage-facility is based in Burbank, LA.

Ringing The Changes

The higher he has risen in the production world, the more Ariel Rechtshaid has sometimes come to realise just how much a pop track can change from its original idea to the finished release, especially when multiple producers are involved in the process. One instance of this was his work on Madonna’s 2014 single ‘Living For Love’, for which he received a co-writing and co-production credit alongside Diplo and the singer. “When I met Madonna, I was such a fan,” he says. “I just kept thinking that we should have some broken-down, almost like more ballad-y song. That was just what I felt like as a fan I wanted from her. I didn’t want to try to make competitive, aggressive pop music with her.

“I said, ‘What do you wanna sing about?’ She has been through so much, she’s such an incredible person and she can just boil it down to a few words. Between all the bullshit in her life with relationships, career, everything else, at this point she just felt like the thing that keeps her moving is the love. It felt positive and honest and it feels a little bit dorky to talk about it in that way. But we just sat down at the piano and started coming up with this piano-type thing.

“Then I remember thinking, ‘Well, we could put a kick drum underneath and it would move. But kinda keep it simple.’ Then, of course, one thing led to another. She’s very much addicted to the high-energy music, and between Diplo and everyone else involved, it just kind of evolved into a little bit more of a monster. My version was very Chicago house. Then it just passed through a lot of hands and was modernised.”

The Difference An Eighth Note Makes

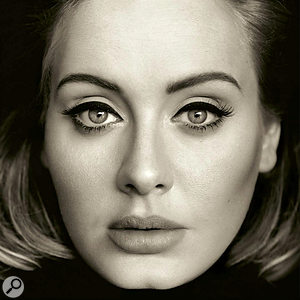

Rechtshaid managed to maintain more control over the final product when it came to Adele’s ‘When We Were Young’, which she’d co-written with his friend, Canadian singer-songwriter Tobias Jesso Jr. The follow-up album to the 31-million-selling 21 was being recorded in London amid some secrecy when Rechtshaid was brought in to produce what turned out to be a key single from 25. He admits he did feel pressure getting involved with what was bound to be a high-profile album. “Yeah,” he laughs. “I mean, not when you’re in the room. She’s such a great person and at the end of the day we’re all just human. The thing about Adele that really takes you aback is when she starts to sing. Having a front row seat to that was maybe the only thing that made me feel a little nervous.”

Rechtshaid managed to maintain more control over the final product when it came to Adele’s ‘When We Were Young’, which she’d co-written with his friend, Canadian singer-songwriter Tobias Jesso Jr. The follow-up album to the 31-million-selling 21 was being recorded in London amid some secrecy when Rechtshaid was brought in to produce what turned out to be a key single from 25. He admits he did feel pressure getting involved with what was bound to be a high-profile album. “Yeah,” he laughs. “I mean, not when you’re in the room. She’s such a great person and at the end of the day we’re all just human. The thing about Adele that really takes you aback is when she starts to sing. Having a front row seat to that was maybe the only thing that made me feel a little nervous.”

The sessions had been originally booked for Metropolis, but Rechtshaid quickly took them over to Dean Street Studios in Soho, mainly because on a previous visit there he’d remembered there had been lots of instruments lying around which he could use for tracking and experimenting. “Tobias happened to be on tour in London,” he says. “The first time I heard the song was there, in person. They were having some difficulty. It was a song they’d written and they really liked it. But there was just a problem figuring out how to arrange it, how to make it into a song.

“Tobias came in, I threw up a bunch of mics on the piano and didn’t really care because I knew that I could re-track the piano in LA with him. I just needed to get it down, I needed a performance of her singing it.” For Adele’s voice, Rechtshaid set up the studio’s Neumann U47. “Got two amazing vocal takes, some BVs I could play with, piano parts. Very floaty. Everything was all over the place a little bit. It was hard to really define the ‘one’, especially when the chorus came along.”

Rechtshaid then brought in arranger Nico Muhly to play overdubs including prepared piano and pump organ. Still feeling there was something missing, he asked Adele to come back into the studio and sing an additional eight-bar vocal section. But even when he returned to Los Angeles with the files, Rechtshaid was still struggling to make sense of the track. Then he tried something subtle but radical.

“It’s hard to explain,” he says. “But after 48 hours of really pulling my hair out, I took her vocal and just played the whole thing an eighth note earlier — and all of a sudden there was a backbeat. I don’t know what led me to try that, but I did and it was like, voila.

“The first time I played it for her, she was like, ‘Wait what?’ But then she was also like, ‘Oh yeah, now it works.’ It’s a mindfuck if I show people sometimes the session, like how it was actually performed and how it turned out. It was amazing.”

Lost Weekend

In 2014, Rechtshaid won a Grammy for his co-production (with the band’s Rostam Batmanglij) of Vampire Weekend’s third album Modern Vampires Of The City, which proved to be a similarly experimental process. “They’d kind of hit a wall,” he says. “Rostam and I had met when I was touring in Foreign Born and we geeked out on things being the internal producers of our bands. He called me he was like, ‘We’re kinda [in] a little rut. Can we come to your studio and mess with some stuff?’ We kind of broke through some walls together, just the type of stuff that happens when you’re too close to something and you can’t see it any other way.

In 2014, Rechtshaid won a Grammy for his co-production (with the band’s Rostam Batmanglij) of Vampire Weekend’s third album Modern Vampires Of The City, which proved to be a similarly experimental process. “They’d kind of hit a wall,” he says. “Rostam and I had met when I was touring in Foreign Born and we geeked out on things being the internal producers of our bands. He called me he was like, ‘We’re kinda [in] a little rut. Can we come to your studio and mess with some stuff?’ We kind of broke through some walls together, just the type of stuff that happens when you’re too close to something and you can’t see it any other way.

“That was an eight-month process of finding the songs and building them, and if it sounded like anything they had done before, we deconstructed it and tore it apart. There were many times when we had something that sounded, by professional standards, radio-ready, like amazing. And then we just kinda thought, ‘Nah, it’s not fresh enough.’ I helped make the weirdest Vampire Weekend record yet so I was very happy that it was well received.”

As for today, Rechtshaid remains incredibly busy and has recently been co-producing the second HAIM record, along with sessions with new Warp Records artist Kelela and Jana Hunter of Maryland dream pop band Lower Dens.

“I’m very fortunate,” he says, “just to have these incredible artists that have become part of this family, whether it’s HAIM or Sky Ferreira or Charli XCX or Diplo or Vampire Weekend or Kelela. Like, I get tired and overworked, but when I hear one of these guys wanna make some music again, I get excited. And different from the days when I was in a band, selfishly I get to do only the fun stuff, which is create something. It ends up being very rewarding, the process of creating something from nothing. Going back in and trying something new.”

Inspirational Kit

For much of his career, Ariel Rechtshaid worked from home, but these days, he has a studio in the LA district of Burbank. “My studios have always been somewhat of a storage facility/studio,” he says. “All my toys and then a computer somewhere in the middle tape machines lying around.” He used to work with a pair of ProAc speakers he’d seen hip-hop producers using, but has since moved onto a pair of PMC twotwo.8s: “They were the right size, so I could travel with them. They weren’t ridiculously heavy. They’re not particularly fun because they give you all the bad news, but they’re very helpful.”

One of Ariel’s two Pro Tools systems is based around UA Apollo audio interfaces with their Powered Plug-in technology, allowing him to experiment with plug-in effects at tracking.

One of Ariel’s two Pro Tools systems is based around UA Apollo audio interfaces with their Powered Plug-in technology, allowing him to experiment with plug-in effects at tracking.

Rechtshaid has two Pro Tools setups, one running HD I/Os and another running two UAD Apollos and a Satellite. “With the two Apollos and the Satellite, the functionality is fucking awesome,” he says. “I’m a slow learner maybe but I’ve started to use Console in it, so that I can record stuff with it. To be able to record a vocal with an AMS [RMX16 digital reverb] plug-in on it without any latency, or to record a bass through the [Ampeg] SVT plug-in, or to use the [Eventide H]910 on percussion and get weird David Bowie Low sounds on stuff, while I’m recording and getting the vibe going, it really was a game-changer for me. Then I can choose to commit it or not commit it, and reopen it up in Pro Tools afterwards with the same settings.”

Pro Tools is of course his main DAW, but he’s equally comfortable working with Ableton Live. For beats programming, he moves between Kontakt kits of drum sounds from his own recordings and, when he has enough time on a project, hardware drum machines. “I have every drum machine, or I have had, known to man,” he says. “When I feel inspired I try to sequence out of the box and see what I can get recorded down, whether it’s an [Oberheim] DMX or my [Roland] 808 or even like a cheap 707.”

One interesting drum experiment with a Linn LM1 drum machine informed the production of ‘Falling’, the first track Rechtshaid produced for Los Angeles trio HAIM in 2013. “There was something about ‘Falling’ I was trying to find,” he remembers. “I could tell what Danielle [Haim, singer/guitarist] wanted and what I wanted was the same, but I couldn’t quite program it in the box. It sounded right but it didn’t feel right. There was a character missing.

“Of course I knew that Prince used this legendary LM-1. I did the same sequence on it and hit Play. I remember going, ‘How do you set the tempo? There is no tempo on here!’ You just have to turn the wheel until about where it feels right. So I figured, ‘All right, I’ll find out what the tempo is afterwards and then I’ll build the track around that.’ I did that and I realised the tempo was shifting all over the place. I mean, not drastically, but it had a life of its own. Really like a little human being in there.

“That was my first time I guess programming music without a click and I just built a beat map around it. It was a subtle thing, but it’s interesting how that gave it a life that it didn’t have before when everything was just on the grid. It was the same thing but it felt completely different. And that was another one of those breakthrough moments.”