Gareth Cousins talks to Hugh Robjohns about the craft of recording music for film, and his work on the recent British blockbuster Notting Hill.

<!‑‑image‑>Great expectations surrounded this year's romantic comedy Notting Hill, which hailed from the same writer and production team as the immensely popular Four Weddings And A Funeral — and it duly lived up to them, breaking its predecessor's record as the most commercially successful British film of all time. The film's soundtrack, which has been a successful album release in its own right, was the province of engineer, programmer and producer Gareth Cousins, an ex‑Abbey Road engineer who now freelances from his base in Stratford‑Upon‑Avon.

Cousins entered the audio industry in 1986, at the relatively late age of 22 after getting a degree in electronics. Thanks to an acquaintance at Abbey Road studios, he managed to get an interview and won a job as a technical engineer. However, when a studio tape‑op position became available a short time later, he was able to move into the part of the music business where he really wanted to be.

As a young tape‑op Gareth was encouraged to work on a lot of different kinds of session at Abbey Road and to experience a wide variety of different recording techniques, including classical, pop and the area where the two meet — film recordings. The film work at Abbey Road was always exciting because the flagship EMI studio didn't get many small films, and Gareth was soon op'ing on major titles such as Aliens, Honey I Shrunk The Kids and Cry Freedom, often working under extremely experienced American mixing engineers like Sean Murphy.

<!‑‑image‑>Gareth takes up the story: "I stopped working on classical recording sessions early on, because I didn't really enjoy it. When you record an orchestra, you can't touch the faders after the first take, because any changes to the balance make editing very difficult. If you were working on an opera you could be in the studio for a week with nothing to do but write the take numbers on the tape box! I have to be more involved in the process than that. Luckily, I was given the opportunity to work with some great rock engineers and producers, and I worked on a Siouxie And The Banshees album and a Toyah album before engineering small sessions on my own. I worked on my first film in 1990, Buddy Song starring Chesney Hawkes and Roger Daltrey. The soundtrack was entirely rock music, and this was my first real experience of serious film music engineering, which I thoroughly enjoyed. We even had the bonus of a number one hit single from it with Nick Kershaw!

<!‑‑image‑>"Since the pop music was more successful than the film side at that time, I did three or four years of music engineering and programming after that. A lot of it was very instrumental in nature (which tends to be done in a very filmic way), such as the first Vanessa Mae album, which has sold over 3.5 million copies. I also did some remixes for Jeff Wayne's War Of The Worlds which went gold. Then, out of the blue, I had a call from a composer called Trevor Jones who was working on the score for GI Jane. He wanted someone to do some programming and recording at short notice, and my name had been passed on from Abbey Road. The project worked out well and for his next film, Lawn Dogs, Trevor asked me to work on it from the start. The producer of that film was Duncan Kenworthy who produced Four Weddings And A Funeral — and that eventually lead on to my working on Notting Hill. I also worked on Desperate Measures and Dark City, which is a cult sci‑fi film. That was fantastic because we had the opportunity to uselot of techno sounds and my programming skills really came to the fore in that. I used a lot of drum 'n' bass influence in the soundtrack which became a hip thing — Lost In Space did something very similar afterwards."

Abbey Road To Notting Hill

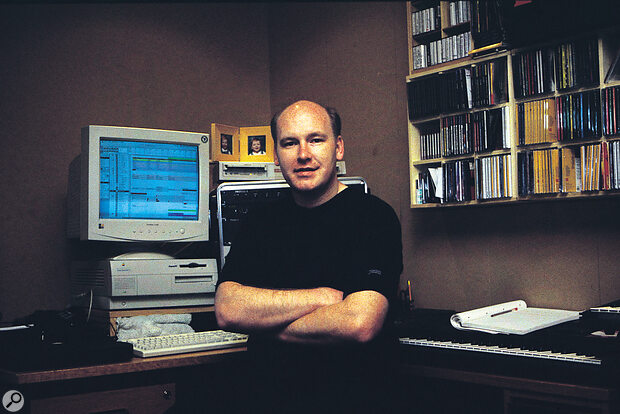

Cousins' Stratford home studio. From left, B&W 805 monitors, Apple Mac G3 and Pro Tools rig, (in rack) Roland JV1080 sound module and Akai S3200 sampler, Roland JD800 synth, Korg Prophecy and Quasimidi Sirius synths.

Cousins' Stratford home studio. From left, B&W 805 monitors, Apple Mac G3 and Pro Tools rig, (in rack) Roland JV1080 sound module and Akai S3200 sampler, Roland JD800 synth, Korg Prophecy and Quasimidi Sirius synths.

Gareth is eager to talk about his work on Notting Hill: "Without a doubt this has been the most varied film I've ever done, and I expect it will be the most successful. Music is really important in the film with lots of songs, some of them scored, and lots of new recordings too, which is where I came into it. Most of the score and new recordings were done at Abbey Road, and I also remixed the tracks which already existed as pop singles, such as the Shania Twain and Boyzone songs.

"One of the big hits from the film is the Elvis Costello version of 'She'. Although the film was conceived with the original Charles Aznavour track, it was thought that it wouldn't appeal to the American market, and so Costello was asked to perform it. However, by the time this had been decided, they had already cut the film to the Aznavour version — and although the budget would probably have been available to re‑cut it, we helped them out by matching the tempo of the new version to the original, beat by beat.

"The arrangement was by Julian Kershaw, who is a genius; I'm a great fan of his. He worked out the original orchestration and then added an 'orchestral bloom' in the middle to suit the screen action and seeded similar ideas throughout out the piece to produce the final version. It's a very middle‑of‑the‑road recording — there are no dance loops or hard drum sounds — but it works really very well.

"Elvis was available for a couple of days when we were already booked into Abbey Road working on some of the other tracks for the film. Most involved guitar, bass, drums, sax, Hammond and Rhodes — quite an old‑fashioned line‑up in a way — which was also the line‑up needed for 'She'. We routined the band for a couple of hours before Elvis came in (so they could get all the complaining about the variable tick out of their system), then rehearsed a few times with Elvis and recorded it in one take! Afterwards Elvis took the multitrack down to Studio 1 and recorded the orchestral overdubs, singing live on it again. I didn't engineer the orchestral session but, after the overdubs, they all came back upstairs to record a couple more vocal lines, and it was all done! That was a very fast turnaround because a normal pop single would probably have taken several weeks to produce."

Without a doubt this has been the most varied film I've ever done, and I expect it will be the most successful.

Film Recording

A scene from Notting Hill, starring Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant.

A scene from Notting Hill, starring Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant.

Having worked on both straight music sessions and music‑for‑film projects, I asked Gareth if the latter required a change in working methods: "Yes, you have to. For example, American audiences like the sound of close‑miked strings, which means putting out a lot more mics than you might otherwise do for a straight orchestral session. I find I mic things quite differently for 'film pop music', too, and with a lot of extra mics you have to be careful to avoid horrible phasing problems, which used to be a real problem with the old Dolby Matrix surround system.

"The only real way to learn surround mixing is to do it, and then listen to the results in the cinema — you can be appalled at the results sometimes! I was fortunate because I was able to learn from people like Sean Murphy working on massive budget films, and then develop my skills on a small film a long time ago. That was with the Dolby Matrix system, which has to be the most horrible thing ever invented! These days we can break all the rules that came with the old LCRS system, but if you still obey those basic ideas you end up with good surround mixes. We used to have to have discrete mono reverbs for each channel of the LCRS system, and instruments had to be panned hard into a specific channel — no half‑panning between speakers. So first violins might be hard left, for example, and seconds hard right with woodwind up the middle, brass hard right, horns hard left, and so on. Now we can pan and spread sounds because we have the six discrete channels, and I like to use stereo reverbs across the rear and front speakers. I don't normally use much compression in my film mixes because the dynamic range can be so much bigger, but I sometimes use compression instead of EQ. If I want something to sound brighter, increasing its level and compressing it slightly works well with some instruments — it achieves the same effect as brightening, but without it sounding thin.

The idea is that the music should support the action on the screen and not distract the audience. The moment the music points itself out, something is usually wrong...

"With the discrete surround systems you can be a little more adventurous in the mixing, compared to normal a stereo mix. Mixing an orchestra for film is pretty obvious, but songs have to mixed slightly differently because they tend to be featured rather than used as underscore. In stereo, you usually put the vocals, bass, snare and kick drum in the middle as a phantom image, but when they are reproduced by a dedicated centre speaker in the cinema it all sounds very different. The way I get around that is to deliberately spread those sounds out towards the sides. The other thing is that you have to be careful not to put too much into the centre speaker — you have to make use of all the speakers if you want to fill the auditorium with sound.

"Once you have sorted out the rhythm, the next question is what to do with the vocals. With the Shania Twain track in Notting Hill I worked on the kit to make it sound like it was in the room about ten feet away, with subtle reflections coming from the back walls to create the acoustic space. I carried on that 'sectorphonic' philosophy in placing all the other instruments, and that eventually only leaves one place for the vocal — the middle of the room! Strictly speaking, this is breaking all the rules, and I knew the dubbing mixers were going to hate having vocals coming from the back speakers — but, listening to the finished film, although the dubbing engineers backed off the rear channels a little, my balances survived quite well. The thing to watch for is not making the singer sound too dry, so I used a little more reverb or effects than I normally would.

"Appreciating what the dubbing engineer has to do is important, and you have to be careful not to get too carried away, putting different sounds in the five channels. For example, having a guitar in the left speaker and its delay in the right turns out to be very distracting, and the dubbing engineer would get rid of it right away. The idea is that the music should support the action on the screen and not distract the audience. The moment the music points itself out, something is usually wrong, although sometimes you want the music to take over — the orchestra blossoms or a song really takes off — and those are the moments the audience remembers.

"If I'm recording piano for a film track I would tend to use three mics, one for each front channel. If it was a straight pop recording you might have a couple of close mics for a hard bright sound, whereas a ballad might use a crossed pair for a slightly softer feel, but in film you don't think of it that way. You have to come in close anyway to create an interesting spread, and it's a safer approach because you are probably recording something that an orchestra will be added to afterwards, and you have to give the person mixing (which might not be yourself) as much flexibility as possible. The biggest problem is with instruments normally recorded in mono, like acoustic guitars. I have solved that particular one in the past by using a pair of omni mics spaced about six inches apart just above and below the outer strings. As long as you are aware of the potential phasing problems, this technique works very well and the omnis give a nicer, more open and brighter sound than cardioids.

"A very important issue to address is how the underscore sits against the film dialogue. Dialogue usually comes from the centre speaker and is always louder than the music, so you have to think 'How can I record this so that it doesn't fight with the dialogue?' Obviously, the music has to be written in such a way that it won't get in the way in the first place, and uses instruments which don't compete with the dialogue. In Notting Hill we had exactly this problem because the director and producer wanted guitars and pianos in the sound track, which do speak in the same range as the voices. Fortunately, the whole music recording process is usually done to picture, not just the orchestral scoring, but right from the first time the sequencer is turned on. When we recorded those guitar parts we actually had the dialogue available on the playback too, so we could hear exactly how the music sat against the voices."

The Abbey Habit

Cousins at the keyboard in his studio, with the Spirit desk in the foreground.

Cousins at the keyboard in his studio, with the Spirit desk in the foreground.

<!‑‑image‑>"Abbey Road, for me, is the best studio in the world, with the best selection of equipment, desks and rooms to record in," maintains Gareth. "The main recording room, Studio 1, has this great big analogue Neve VR console which is probably the best recording desk. Studio 3 is my favourite pop room, with lots of wood everywhere and an SSL Ultimation moving‑fader console, which I think is the best for pop work. The Penthouse has a digital, assignable AMS Neve Capricorn mixer which has to be the best for film mixes. Whatever you want to do, in terms of outputs and routings, you can do on the Capricorn, although you have to plan it all before you start because changing the desk configuration later can really screw you up! But careful planning is worthwhile, because you can have eight different mixes all happening at thsame time if you want! For example, on Dark City I wanted to give the dubbing engineers the opportunity to re‑balance the orchestra against the synths, and so I made three different eight‑track mixes all at the same time, plus my combined eight‑track master of everything, as well as a separate stereo mix! There aren't many desks you could do that on!

"That was an unusually complex example and, although it is often possible to make a stereo mixdown at the same time as a main multi‑channel mix, you sometimes have to go back and fix things. Surround mixes obviously contain a lot of atmospheres and 'flying effects' that simply don't translate to the stereo mix, but on Notting Hill the production team really cared about the quality of the soundtracks and, although the budget probably wasn't comparable to some of the big Hollywood films, I was always allowed to spend the time getting the multi‑channel and stereo mixes exactly right.

...you always have to remember that the orchestra has to play the thing you have sequenced! It's generally better to make a tempo adjustment rather than slip in the odd 3/8 bar, even if that's what you really need to work with the picture.

"I didn't record any of the orchestral scores for Notting Hill, although I have done the scoring on other films, because I was busy recording and mixing the band tracks in another studio while the orchestral recordings were being done. Sometimes Notting Hill tracks were being recorded in three different studios at Abbey Road all at the same time, and we tracked everything onto Sony 16‑bit DASmultitracks because Abbey Road has them in every room. The final six‑channel mixes all went off to the dub on Genexes, with backups on Tascams and the Pro Tools."

Last Minute

One typical feature of film work is that films are often still being edited very late in the production process. This, of course, can make things very difficult for the music producers: "Re‑cuts can cause a lot of problems. Conforming the music for a re‑cut is as complicated as writing it in the first place, and is a skill that you can only acquire if you have been programming on the film from the start because you have to understand what the composer was trying to do. It is a heartbreaking process to chop the music up trying to make it fit but, if you are lucky, the film editing will be done before any serious recording has taken place, so all you are conforming are the 'sketches'. For example, I sequenced a guide guitar part for Notting Hill which Clem Clemson played into the Pro Tools. When the film was re‑cut later and we had to change the tempo, I was able to do it all in Logic — stretching or chopping it up into little notes and using something like Recycle — I'm a recent convert to that particular process.

"Once the conforming has been done, the orchestral arranger will hopefully be able to 'gloss over' any 5/4 or 3/8 bars you might have had to put in, but you always have to remember that the orchestra has to play the thing you have sequenced! It's generally better to make a tempo adjustment rather than slip in the odd 3/8 bar, even if that's what you really need to work with the picture. Listening to a click track with four beats to the bar and then suddenly getting three quick ones can easily throw a musician, and if one person in an 80‑piece orchestra gets it wrong three minutes into a four‑minute piece, no one is very happy!"

The Cousins Home Studio

"I don't actually use my studio very much when I'm working on a film, other than maybe for some sampling or to separate‑out some loops. However, I'm recording a music project at Abbey Road soon and I'll be doing all the pre‑production work here, including recording some of the soloists and most of the programming. The room is built into what was originally the garage, and I have lined it with an inch of polystyrene with wall coverings and carpet on the floor. It's not fantastic sound insulation but is good enough and I really couldn't justify the expense of doing the job properly. The room sounds quite nice though and I don't get too hung up on sound equipment and sound anyway. The truth is that you can make anything sound good if you have good musicians and good music!

"I mainly use a Pro Tools system with a 9Gb Rourke Data drive on a G3 PowerPC for recording and sequencing, but with Logic as the front end. I believe you can do everything in Logic now that you can do in Pro Tools and, on a TDM system, you can even use all the standard plug‑ins. At the moment I'm using a lot of VST plug‑ins which are really good quality and are usually a lot cheaper than the TDM equivalents. The Auto‑Tune VST plug‑in, for example, costs two or three times less than the TDM version but the quality seems the same to me. I'm about to rack the whole system up so I can take it with me when I work in other studios. I have found it is far easier and quicker to take the whole computer, rather than try to configure someone else's system to run my sequences.

"My most important sound source is an Akai S3200 sampler with 32Mb of memory, but I also use a Roland JD800 a lot. Basically, if a sound starts as a sample I use the S3200, but if it starts in my head I program the JD. I have a JV1080 which is a fantastic little workhorse, but I'm bored with the presets and it isn't really hands‑on enough to program. I have also have a Korg Prophecy which I always think I use more than I actually do! I often start with a Prophecy sound when I'm programming, but somehow I always seem to have replaced it by the time I'm finished!

"Just before Christmas I bought this Quasimidi Sirius because I heard a really good demo... don't trust guys with really good demos! I didn't have enough dance sounds and I thought there would be lots of good sounds in the Sirius to inspire me when I have to do something 'dancey'. Unfortunately, though, I seem to end up programming my own sounds on it all the time. My other sources include a Proteus 1 and a Yamaha DX11, which I keep for the occasional FM sound. Those DX brass sounds which were so popular in the '80s might well come back again, so I'll never get rid of it!

"Everything feeds into a Spirit desk, which sounds similar to the Mackie but was a lot cheaper — the EQ isn't as sweet but I really just use it as a monitoring station. It's a good‑sounding desk as long as you watch the levels, because you can't drive it hard. I have a Fostex DAT machine and an ADAT which I hardly ever use now I have the Pro Tools, and I love my TL Audio C1 compressor for warming up a vocal, or to make a mix more solid. There is also a Yamaha SPX990 multi‑effects processor which is great, and I use a lot of plug‑ins. I have a Drawmer gate, too, but recording to hard disk means you don't use gates the way you used to — they are more of an effect now than for cleaning up a noisy track.

"The monitors are B&W 805s, which I think are the best little speakers ever built, and I always specify when I'm mixing at Abbey Road. In fact I hardly ever use their big Quested monitors at all for album work, although you have to use them for film mixing because you have to hear the music on the same kind of scale as it will be heard in the cinema."