It's hard enough to reach the top in any field, be it engineering, production, programming or playing an instrument, but Michael Bradford has excelled in all of these departments — and often while travelling across America at 80 miles per hour! Richard Buskin meets a man who's helped to create massive hit albums for Kid Rock and the New Radicals.

<!‑‑image‑>"My mantra is 'It's not my record,'" says Michael Bradford. "You know, my name isn't on the cover. I might have opinions, I might have suggestions, but at the end of the day, when the record is on the shelf, the artist is living and dying by that record. The best I can do is help guide the process. I've seen a lot of big producers approach things as if they're the artist employing a singer, but I don't do that. I mean, artists hire me for a lot of reasons, but what they don't hire me for is my ego."

No, what Kid Rock, Uncle Kracker, Run DMC, New Radicals, Anita Baker, Terence Trent D'arby, Annabella Lwin, Madonna and numerous others have hired Michael Bradford for during the past few years are his multi‑faceted talents as a songwriter, producer, engineer, remixer, programmer and musician. Bradford, you see, is also adept on the bass, guitar, drums and keyboards, and while this may sound like a lot of ground to cover, in no way is he the proverbial jack of all trades, master of none. The range of his abilities means that Bradford gets hired in a variety of roles, from collaborating or co‑writing to simply getting a good sound on material that has already been written.

"For me it's really crucial to understand what the artist is basically trying to say through the record," Bradford explains. "That is, assuming the artist is actually trying to communicate some sort of deeper message, as opposed to just singing the song. Both kinds of record are valid — some are purely entertainment, whereas others have this whole level of communication going on, and if you're lucky enough to be part of one of those records, I think it's really important to listen to what the artist is trying to say. You can be of maximum use by just helping him or her to bring that out and get their point across. Then you can actually say, 'It sounds like this is what you're trying to communicate in your song, but this thing is obscuring it. Maybe if it wasn't there it would be clearer.'

<!‑‑image‑>"I can sit with a guitar player and suggest other guitar parts, or I can suggest maybe a different position on the guitar that will produce the same notes that he wants but are easier to play. I can help him solve his problems without saying, 'I'm a better musician than you,' because that's not what making a record is about. At least it shouldn't be, although again I do know there are guys who have different methods. They'll say, 'I don't care, I just want the record to sound good,' but that artist has got to go out and perform the thing night after night if the record is a success. He has to live with himself, and no one likes to feel that someone else has made their record for them, unless they hired the producer for that specific purpose."

The Learning Curve

Michael Bradford in the work room at his Los Angeles studio.

Michael Bradford in the work room at his Los Angeles studio.

Having played guitar since the age of six, Detroit native Michael Bradford made his pro start as a bassist for reggae band The Heptones during the late '70s. Next switching to jazz, he learned to play a variety of instruments while acquiring an interest in the recording studio, and soon he began writing songs and making demos on his Tascam Portastudio.

"What I really wanted to be was a songwriter," he says. "However, the only way I could get my demos done was to do it all myself, because if I would write a song and ask someone else to play guitar, either they'd start suggesting all of these other parts that I didn't want or they would want to be credited as a co‑writer because they played a wah‑wah. It was easier for me to do it myself, and necessity being what it was, I became quite adept at doing it fast, because I'd sometimes only have a few hours to work on my own little ideas before returning to my other gigs."

<!‑‑image‑>In the process, Michael Bradford learned a lot about multitrack recording, and he also acquired a part‑time job as an assistant at Ambience, one of Detroit's top studios at that time, frequented by the likes of Bob Seger and Anita Baker, as well as advertising companies recording commercials. Limited in terms of how much high‑calibre work he could do in Detroit, Bradford relocated to Los Angeles at the end of the '80s. By then, as a full‑time freelancer, he had already become adept at programming MIDI and using early versions of Pro Tools. "Sound Tools was the first thing I used," he recalls. "Then, as it became more of a multitrack thing instead of just a stereo editing and mastering tool, I grew with Digidesign. Consequently, I was among the first people to really want to record and work purely in Pro Tools whenever I could. You see, even though I had an analogue background, what attracted me to Pro Tools was the fact that, when the plug‑ins became available, you could mix in it and have instant recall. I could see how advantageous that would be if you were switching from session A to session B and not have time to re‑document everything and reset all of the controls. For me, Pro Tools' ability to reset was just amazing, because you weren't just automating the console, you were automating the outboard equipment; you were automating the mix.

"Even today, I'll be working on something, and suddenly a record company will call and ask me to run a special mix of a record that we've done two months ago for a movie or TV show, and I'll say, 'Sure.' I can literally load that session which will already be exactly the way it was, make my changes, bounce it down, make a DAT or whatever they need, and then return to my other session. If I had to do that on tape it would be bad news. It would be a bad phone call."

The Programmer's Part

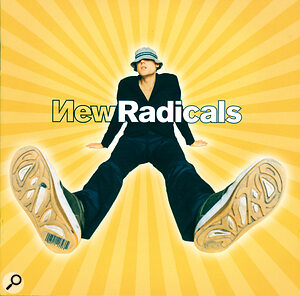

Michael Bradford contributed his engineering and programming skills to the hit debut album by Gregg Alexander, aka The New Radicals.

Michael Bradford contributed his engineering and programming skills to the hit debut album by Gregg Alexander, aka The New Radicals.

On first moving out to LA, Bradford found it easier to obtain work as a programmer. "As a programmer doing MIDI I ended up using Pro Tools to a degree," he says. "So, I was sort of engineering too, and if I was writing the song that I was programming then I might be credited as the writer, and I might also become the producer if they used the track that I had built using MIDI."

Then, of course, there were his aforementioned multi‑instrumental abilities. Want some keyboards? No problem. Need a guitar? Sure thing. How about some bass and drums? "For the first few years out here I was sort of a Swiss Army knife," Bradford says. "I was able to sneak in a lot more work that way, and also, because I was involved in the session on the programming level, I was seen almost as a second producer."

His best instrument being the bass, Bradford nevertheless views himself primarily as a songwriter and record producer. "The engineering and all of those instruments are just the tools that I use to get the job done," he says. "When I write a song the whole number is pretty much in my head before I ever sit down with an instrument. I've got perfect pitch and I can hear the music in my head before I play it. I can hear the strings, I can hear the whole thing, so for me it's really a case of imagining the way things will sound and then coming up with a lyric that I think will help."

Michael Bradford's most high‑profile projects of recent years have included his soundtrack contributions with Hans Zimmer and Terence Trent D'Arby to the 1996 movie The Fan — "That was remarkable sounding. We built it from the ground up with MIDI, and the only natural instruments were guitar and bass," — and his 1999 engineering and programming work on The New Radicals' album Maybe You've Been Brainwashed Too.

"That was all Pro Tools work," he explains. "A lot of that record was originally recorded on analogue, but then a big part of putting it together came down to assembling different takes from different reels in Pro Tools. At the time, [New Radicals main man] Gregg Alexander's general method was to record a basic rhythm track with the band to analogue tape, put up slave reels for a stereo mix, and perhaps have other guitar players come in and add new parts. Then he might make another slave reel for pianos and another slave reel for extra vocals. We'd end up with several reels of tape, although ultimately we could only use 48 tracks, so a major part of getting the actual record together was deciding which tracks of each slave reel would make good additions to the basic tracks. It was a big assembly process, and we did that at my studio here in Burbank.

"The process was confusing to me, but I think Gregg knew what he wanted all along. He was just waiting for the people to play it. As the producer he was always heading towards something, whereas I would sometimes wonder, 'Why do we have all of this extra stuff that we can't use?' I mean, he wrote the songs and he was producing the record, so it was definitely his show. My level of input was to make sure it all lined up where he wanted it to, while as a musician I would also say if the parts were helping or not. The problem to me was that there were so many of them. Depending on which ones you used, you'd end up with a different result, but they were all good parts, so the question was 'Which part do you want?' not 'Is this part good and that part bad?' To me, it was a pretty heavy way of doing it, but I don't think Gregg himself was ever confused."

Rocky Road

Michael Bradford's vocal mic of choice is the impressive‑looking CAD VX2 valve mic.

Michael Bradford's vocal mic of choice is the impressive‑looking CAD VX2 valve mic.

The resultant New Radicals album turned into a major hit, and the knock‑on effect for Michael Bradford was that it provided him with bona fide rock & roll credibility alongside that which he had already established in the field of R&B. The past couple of years have also seen Bradford enjoying another musical outlet in the form of playing bass on the road with Kid Rock, the fellow Detroiter whose multi‑platinum album The History Of Rock he co‑produced and engineered in a unique 'rolling studio' which they had put together aboard a tour bus.

"I've known Kid Rock for about 10 years," says Bradford, "and when we went on the road two years ago the original reason they brought me along was to help them record Uncle Kracker's Double Wide album. That was why we set up the studio on the bus. We took the rear lounge out of one of the buses, providing me with an empty room to work in, so I set up a rack of Pro Tools back there, a rack of MIDI, a rack of outboard, a Mackie HUI, a pair of Mackie HR824 powered monitors, and then we had some guitars and drum machines in the bay of the bus that we could pull out when we needed them, as well as a couple of microphones. The Emu MIDI equipment is rackmountable and it doesn't take up a lot of room, so I was able to have a lot of gear and relatively not take up a lot of space.

"I was programming drum beats while we were rolling along at 80 miles per hour, and if Kid Rock wanted to play guitar or anybody else was playing an instrument — if the keyboard player was putting some parts down or whatever — everything was mounted in the bus and they could just sit back there and do their thing. We had the whole system running and I had everything on battery backup power supplies, so they were getting isolated clean power from the bus, and if the bus's generators did anything erratic we wouldn't be affected. That's the only way to do it if you're going to be on a bus, otherwise you'll be a victim of the up and down effects of the generators."

<!‑‑image‑>Not wishing to be away from his children in LA for an extended period, Michael Bradford agreed to help Kid Rock record the Uncle Kracker album as a friendly favour on the proviso that it would only take five weeks. In the event, the gig took just a little longer... 18 months, to be precise. "We did the first five weeks, and then Kid Rock said, 'Well, we're not quite done. Let's go back home to Detroit for a while," Bradford recalls. "Being that I'm from there it wasn't so bad, but I was missing my kids and I'd only get to see them maybe a couple of days a month. Anyway, I stayed there for a couple of months, and then he said, 'Oh, you know we're going on tour again. Why don't you come along? We're not done on the album.' So, we set up the bus again, and this time he said, 'As long as you're here every night, why don't you play bass?'"

Kracker Barrel

The main equipment racks in Michael Bradford's studio. The left‑hand rack contains, from top: API 3124 mic preamp, Mackie 3304 submixer, Emu Planet Phatt and Orbit sound modules, TC Electronic G Force guitar effects, Clavia Nord Rack synth, Akai S1100 sampler and Emu 6400 sampler. In the right‑hand rack are his Clavia Nord Modular synth, Line 6 Pod guitar preamp, Tascam DA20 DAT recorder, a selection of MIDI and audio interfaces and a Glyph removable hard drive.

The main equipment racks in Michael Bradford's studio. The left‑hand rack contains, from top: API 3124 mic preamp, Mackie 3304 submixer, Emu Planet Phatt and Orbit sound modules, TC Electronic G Force guitar effects, Clavia Nord Rack synth, Akai S1100 sampler and Emu 6400 sampler. In the right‑hand rack are his Clavia Nord Modular synth, Line 6 Pod guitar preamp, Tascam DA20 DAT recorder, a selection of MIDI and audio interfaces and a Glyph removable hard drive.

For the first two months Michael Bradford lent his talents exclusively to the Uncle Kracker record, and then when Kid Rock began to execute his idea for the History Of Rock album there was a period during which the men worked simultaneously on both projects.

"Depending on which day it was, we'd work on one record or the other, and it was because of Pro Tools that we could do that," says Bradford. "I couldn't imagine being on a bus and switching from project A to project B within the same day any other way. You know, to be able to yank out one hard drive and stick another one in, bring up the previous mix, and keep overdubbing or editing from there; it would have been impossible without Pro Tools."

Uncle Kracker's music is similar to Kid Rock's in that it features rapping as well as singing. However, it also far more laid back and melodious than the in‑your‑face rock sounds of the Kid.

"Kracker co‑writes a lot of Kid Rock's songs, and he just has a natural way with a melody," says Bradford. "He's not a trained musician and neither does he have a lot of experience on different instruments, but it's in his head. He's just naturally musical, and I'm sure that if he had the chance to practise playing the guitar or any other instrument he'd be great at it. If you're a good musician, the music's in your head and you're just looking for an instrument to play it on. Otherwise you're just a good technician.

"People think Uncle Kracker's a rapper or a DJ because they see him at the turntable, but what's really brilliant about him is that he's got a great musical mind, and when you take a hit song like 'Follow Me' which he and I wrote, a lot of that melody he just had in his head. He came up to me one day and started singing it a capella, and I said, 'Well, there's a hit song. Thanks for bringing it here.'

<!‑‑image‑>"He came to me with the chorus melody: 'Follow me and everything is all right...' and I said, 'Wow! That's a hit!' Then he started singing the verse, and at the time the verse lyrics were very different to what they are now, but the verse's melody that he came up with was really catchy. He would sit there and sing this thing, and I'd come up with chords to go along with the basic melody idea that he had. Then, where the producer part would come in was when I'd say, 'These lyrics are OK, but could they be different?' He would say, 'Well, how about this?' Like the song needed a middle eight, so I wrote chords for a bridge and said, 'How about if the bridge went this way?' and he said, 'Well, we could do that, but how about this, because this is more the way that I sing?' So, the song started out as a sort of a capella skeleton of a verse and chorus idea, and then by adding parts and coming up with chords for it we were able to develop it into a real song within a couple of days.

"He already had the basic melody and the chorus lyric in his head, and where I came in handy — aside from writing all of the chords and the bridge for him — was just encouraging him to finish it. A lot of times the producer's job is just to help the guy finish his idea and get the song done. It's easy to get discouraged, and for an artist like Kracker a song like 'Follow Me' was risky because he had this image of being with this hardcore band. You know, he's a rapper and he's got this gold tooth, and then here comes this very melodic, pretty song. What will people think? My answer was, first of all, 'When you've got a hit song nobody complains,' and secondly, 'Who would you rather have in your audience? 13‑year‑old boys or 18‑year‑old girls? Personally, I'd prefer the girls.' Having a bunch of kids thinking you're hardcore is cool, but having a bunch of young girls in the audience is cooler. Besides, girls buy more records. So, I encouraged him to finish the song, and I think that was important, because that song obviously made the album a hit.

"For that number I used a guitar to write because I happened to have one laying around. There's always a guitar around and so it's often easier to write that way. There's not always a piano around, and if there's a keyboard it's not always turned on and ready to go, whereas the beauty of guitars is that they're always booted up, they're always running. All you have to do is play them, provided that they're in tune. Anyway, a lot of 'Follow Me' was cut in the basement of the house where I was staying in Detroit at the time. Kracker came over, and I played the guitar, the bass and programmed the drums, and then we had our keyboard player come by and overdub some parts as well as sing most of the backup vocals. The rest of the album was literally recorded on the road while we were travelling, and also in the garage of the guitar player's house in Detroit where the band would rehearse, in my basement, at Kid Rock's house where he had a little Pro Tools setup, and finally at this small studio in Detroit that we set up to do the live overdubs for the History Of Rock album."

Metal Kid

The aforementioned Kid Rock opus evolved largely out of previously released material from his pre‑Atlantic indie days, transferred onto Pro Tools and spruced up with new instrumentation or cleaner mixes, while other songs were completely re‑recorded. Then there were a couple of brand new numbers: 'American Badass', which turned into a big hit, and 'F••k That', which appeared on the soundtrack of the movie Any Given Sunday.

"For 'American Badass' we used a sample from Metallica's 'Sad But True' as the basis of the track," Michael Bradford recalls. "Kid Rock's also a DJ, and sometimes he'd DJ at parties and cut between Metallica and maybe a hip‑hop song. That's part of why he sounds the way he does, always mixing rock and hip‑hop together as a DJ. So, he took the CD of 'Sad But True' to a mastering lab and had it pressed onto vinyl — we couldn't find it on vinyl anywhere — and that way he could scratch it. I dropped the musical sections of the song without the lyrics into Pro Tools and started editing together something that could serve as the basis of the track, and then he started coming up with a rap for it, while band members like the guitar player added a lot of overdubs. There's also a cool middle section with live drums, and those were added in Detroit by Kid Rock's drummer after the tour was over. I played some guitar and bass on it, but the main work that I did on that song was in the editing process, helping put it all together. Kid Rock definitely had a vision of how he wanted the song to go, but that kept expanding. He kept coming up with new parts.

"'F••k That' was different. It was cut in the guitar player's garage. Kid Rock programmed the drum beat, I started fooling around on the bass, the guitarist came up with a part, and that was sort of the jam of the song which Kid Rock sang to. The environment that we were recording in was kind of fun, plus there was a bar nearby and he wanted a bunch of people to chant the 'f••k that' refrain in the chorus. Suddenly all of these inebriated people showed up and they were all going 'f••k that!' I'm sure they had no idea where they were, they probably don't remember anything, but it was a lot of fun.

"For me it was fun just doing it on the road and in that environment. You read a lot now about people recording on their buses, but I don't think anybody else was really doing it like we were two years ago. Limp Bizkit were on tour with us for a while and they had a little Pro Tools setup on their bus, but it was just a small computer, nothing like what we had. Now a lot of bands are doing it. A lot of bands dropped by our bus on the road, and they were probably all kind of inspired by it. I mean, I didn't consider it to be some type of trade secret. Jackson Browne had recorded on his bus at least 20 years ago, so we didn't invent the concept."

The Engineering Situation

As usual, Bradford took care of the miking, recording Kid Rock's vocals with a CAD VX2 which he describes as "one of the best sounding mics I've ever heard for vocals. It's a tube microphone, it's got two tubes in it, and it's blue. You can't go wrong with a blue microphone. Artists love it because it looks so damned good, and it just sounds great. It seems to capture every little nuance and I love that, because generally when I record vocals I don't use any EQ or compression on the input stage. I work on mic placement and coming up with a good mic pattern, and I tend to record through a preamp straight into the computer. Then, if I do any compression or EQ, it's during the mix.

"So, the VX2 is very good for that, and it's my favourite vocal mic, but the other mic that I use a lot is the Shure SM7. It's like the big brother of the 57 and it sounds great, but it's a dynamic mic, so if you're a singer like Kid Rock or Bob Seger who really put out the volume and are also used to working live with their mouths very close to a hand‑held mic, it may not be the right one to use. It's not designed to be a hand‑held mic, but it is designed to handle a voice that's right in front of it and it doesn't falter at that point. Those are my two favourite microphones for vocals, and another mic that I use from time to time is the AKG C414, which tends to work for singers whose voices are a little thinner‑sounding if the whole idea is to capture that thinness."

<!‑‑image‑>As Michael Bradford invariably DIs the bass unless he's presented with a hard rock band in a very large recording space, mic placement on the tour bus was never a problem. Fitting a drum kit on there would have been a tighter squeeze. "We put them in the parking lot for Uncle Kracker's record," he says. "Some of the arenas have huge parking areas for the buses, and sometimes those areas are indoors. At the beginning of 2000, when we were on tour with Metallica, we took a Pro Tools system with us, but at that time it wasn't built into the bus. Instead we would take it up to our hotel rooms, because by then most of the work was done and we didn't want to be sitting on the bus in the middle of winter. Whenever we had an overnight stay we would take the Pro Tools system out of the bay of the bus and roll it upstairs in its big rack, but there were also a couple of times when the record company needed to receive a last‑minute mix of something right away.

"I remember one time when we were in an arena parking lot, they needed the mix right away, and there was no time for Fedex unless I did it right then. So, I set up the Pro Tools right next to the bus, ran a power cord into the bus, and while the system was up and running I grabbed a microphone, got a couple of extra drums, and started recording some drums outdoors. When I worked with Terence Trent D'arby we did the same thing for a guitar solo on this song called 'Letting Go', where he wanted to hear the sound of the guitar amps outside. We were at a studio in LA that was owned by Dave Stewart of The Eurythmics, a beautiful old mansion‑type house with a guest house down the hill where Seal was staying at the time, and breaking the picturesque silence was a Marshall. I'd therefore done it before, and so I thought, 'This will be fun.'

"During soundcheck in the arena I had a second Pro Tools 5.0 system that was running on Windows NT, and I hooked it up to the front‑of‑house console, the drummer would play just beats and so on, and I would record them directly into Pro Tools from there, giving me some cool different sounds and ambiences to work with. Plus I was running a DAT during soundcheck, and I could get some drum beats from that too and make samples out of them... Improvisation. That's the name of the game. I mean, if you have plenty of time and nothing to do, and you're in this cavernous cement space, you might as well get busy."

Michael Bradford's 'Chunky Style Gear'

A big, beefy guy with a penchant for making big, beefy‑sounding records, Michael Bradford aptly names his production company Chunky Style Music. Accordingly, he also has his own chunky style setup at a post‑production facility named Millennium Sound. Mostly MIDI‑related or used to run Pro Tools, this collection of equipment is pretty comprehensive:

- Akai S1100 sampler.

- Alesis ADAT digital multitrack w/BRC.

- Apple Power Macintosh 9600 running a Digidesign Pro Tools 5.1 Mix Plus system.

- Casio RZ1 drum machine.

- Clavia Nord Rack and Nord Modular synthesizers.

- CM Automation Motormix.

- Compaq AP500 Pentium III with Windows NT running Pro Tools 5.0 Mix Plus System.

- Emu E6400 and Emax samplers, Orbit and Planet Phatt sound modules, and E‑Synth keyboard.

- Korg M1R and N5SR sound modules.

- Line 6 Pod and Bass Pod.

- Mackie HR824 hard disk recorder.

- Mackie HUI control surface.

- Mackie 3304 mixer.

- Yamaha FB01 sound module.

"The common factor with most of my gear is that it happens to work," says Bradford. "All of the stuff that I tend to use is well made, very reliable and very versatile. I don't believe that any one company has a monopoly on sound. Everything is done through Pro Tools, and the Mackie 3304 is basically a 16‑channel stereo submixer through which I route all of my keyboards via a patchbay system. I still have to do MIDI tracks before I commit them to hard disk, so I just use the Mackie to monitor what I'm working on, and then two channels of Pro Tools get fed through it too.

"The reason why I have a fair amount of Emu gear is because in my experience it is a lot more versatile, and boxes like the Phatt and the Orbit have good pre‑made sounds which you can modify and filter quite heavily. Now, if I'm creating a brand new sound that no one's ever heard before, chances are I'll use a modular synthesizer. That's where my programming background comes in. You see, when I talk about being a programmer, I talk about designing sounds and programming synthesizers, as opposed to what people often call a programmer, which is just a guy with a drum machine. The Emu gear is a lot more programmable than the synths of many other manufacturers — you can actually do things with filters, and assign MIDI controllers to certain parameters and get a lot more versatility out of the unit. As a result, even if you are dealing with a 'canned' sound, so to speak, you can process it to a larger degree on the Emus than on some of the other gear.

"If I had my way I'd always work digitally. When I'm working in Pro Tools, I'm sort of recording and mixing and developing all at once, so that by the time we get close to the end of the recording process, not only does the song sound good but it's pretty much mixed. I've already added EQ, grouped things, and done edits and comps — I don't like to have a bunch of extra parts laying around, so I'll start editing them, decide which takes are the best and put them together as I go. If I do that in Pro Tools, when it's time to mix I'm almost done, whereas if I did that on tape the editing would take another couple of days, and if I wanted to switch from song A to song B then we'd be switching the console and the outboard gear all over again. The ability to switch from song one to song three and have the computer reset just the way it was is a godsend to me."